There’s too much demand and not enough elk.

Elk are blessed with a unique physical feature that has been a point of delight around the world for thousands of years: They grow velvet every year.

The first wave is velvet on their baby horns, which naturally drop between February to April. The next velvet comes in on their full-fledged antlers, which also drop every subsequent year. Velvet is actually a sensitive skin with blood vessels, with full sensation. When their antlers are full-grown in August, they wander around and scrape the velvet off on tree trunks to reveal the bone underneath. It’s a rite of passage.

Velvet is one of the many reasons why Diana Molenaar loves raising elk. They’re smart, they don’t smell bad, they’re large — 800 to 1,300 pounds apiece — “and they’re pretty,” she says.

She and her husband own the Timber Butte Elk Ranch one hour north of Boise. They have 84 acres on high, dry land. About 37 acres are fenced, which is where her 100 head of elk live. The elk eat on fresh grass pasture for six to eight weeks in the spring, and feed on alfalfa the rest of the year. Those first velvet sheds also serve a unique purpose: They’re collected and cut up for dog chews.

This is one of many applications of elk. The industry is strong, and the price of elk is solid and high. But the future of the elk market is at a crossroads, and could end up being many different things that appeal to different people.

What would it mean for the elk industry to shed its own velvet, and keep growing?

Historic Distribution

Elk, much like bison, are native to the United States. Their historic distribution was vast, from New Jersey to California. The only places they were not native to were Florida and New England. In the wild, their biggest threat is encroaching humans. The elk industry was booming in the 1990s because for thousands of years, elk antlers sheathed in velvet have been a component of Chinese medicine, and sold for between $35 to $110 a pound. Elk meat was also higher than beef back then, and was about $4.50 per pound versus $0.80 for beef. But the real moneymaker was the antlers.

But the bubble burst across the global market, even with plenty of sales, when elk started to get sick with conditions like chronic wasting disease. Combined with continental drought that forced farmers to pay more for feed, elk farmers exited the market, and only a few are left standing.

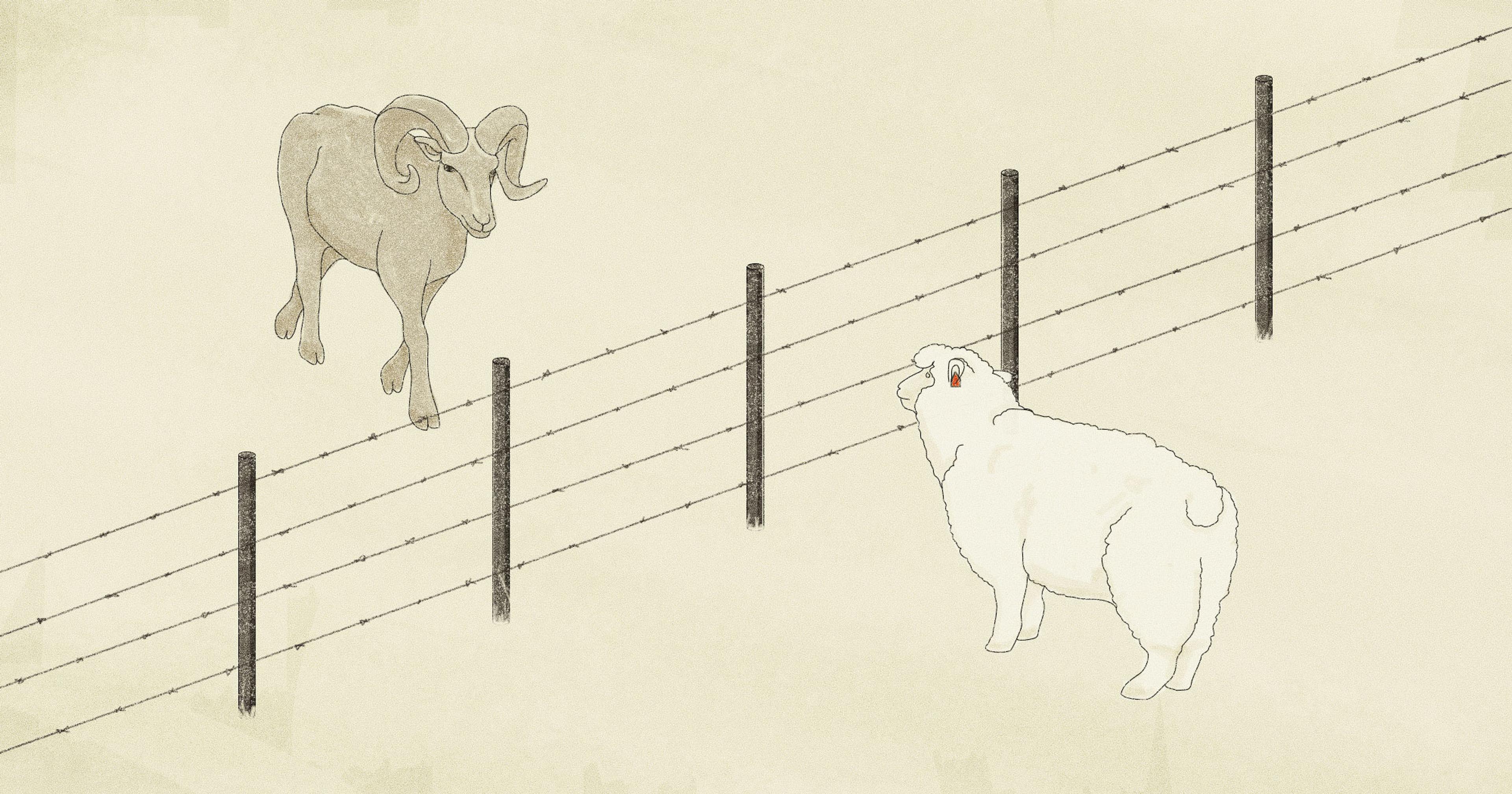

One curious aspect of elk meat is that any elk raised in captivity has long been separated from their wild counterparts. Elk raised for meat aren’t wild anymore, and their previous generations have been domesticated for decades. There is a hard line between wild elk in the Yellowstone Valley and what is harvested at an elk ranch or farm. Those animals have no relation, and it is illegal to capture and breed any wild elk.

“It’s really hard to compete with [New Zealand] supply-wise. We don’t have enough to sustain U.S. demand. We just don’t.”

Robert Northrup, an elk farmer in Luddington, Michigan, has 130 acres with about 110 elk roaming throughout the year. The farm is open to the public in the summer when there are wagon rides to see the animals. But the farm isn’t for elk meat.

“Our primary goal is to raise breeding stock,” he says. When it comes time for animals to be sold, a good amount stay in Michigan, but others go as far as Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Idaho. Most of the stock goes into the shooting market for hunts. That means that a high-fenced elk hunting outfitter in the larger Yellowstone region may very well be stocked with trophy elk raised in Michigan — they would be significantly easier to hunt.

That’s because elk raised in captivity tend to be bigger. Elk are measured by inches of antler, and one of Northrup’s elk is typically 600 inches. If one finds a 400-inch elk running in the wild, that’s “extraordinary,” he says. The size of the antlers is the big draw for hunting lodges and outfitters.

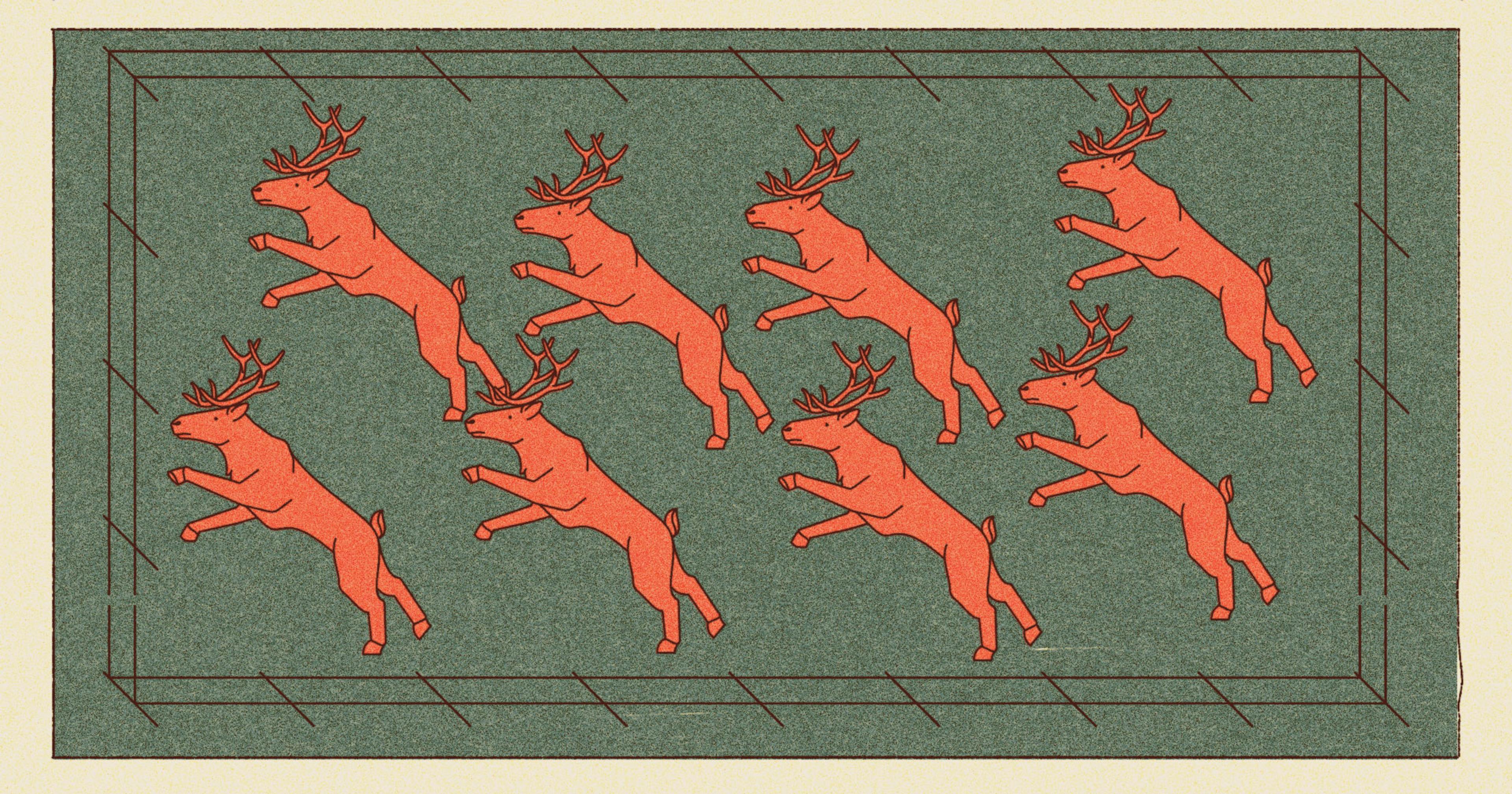

However, the deviation between domesticated and wild stock is a big headache for hunters. If a domesticated elk or deer breaks out of its fence and mates with a wild one, diseases can be spread between herds. That means that sick domesticated elk have to be culled at the owner’s expense, and wild counterparts can continue spreading different genetic variations that the population doesn’t have.

Plus, domesticated elk aren’t afraid of humans, so they and their young may not have the same instinct to hide or run from a hunter. Fencing can also be problematic because private elk ranches can border public grazing lands that wild herds would otherwise use, but don’t have access to. Some hunters argue that the very existence of commercialized elk and deer ranching is deteriorating the richness of those wild creatures and their habitats.

Dollars and Cents

“The elk market is extremely strong,” Northrup says of the live sales sector for breeding and hunting. One reason for that is the elongated breeding season. An elk can’t have a calf until they are two years old, and when they do give birth, it’s typically to a single calf. It takes time for more stock, whether live animals or meat, to enter the market. Northrup has been sold out of birthing cows for six years straight, and has a waiting list. The market for shooter bulls is also strong because there is a shortage.

On the other end of the spectrum, Morgan Cummons, an elk farmer and rancher from Del Norte, Colorado, has about 190 elk in 140 fenced acres. She raises elk for meat, and her team ships out elk, bison, rabbit, whitetail deer, and goat meat. Yet for all of the different products she carries, elk is the bread and butter and constitutes about 65 percent of sales — much of it online, from around the country.

“There aren’t a lot of outlets for elk meat. We definitely have a niche market, and are one of the top competitors,” she says. Her ground meat ranges between $10.95 and $12.50 a pound.

Similarly, Molenaar says that every time she processes elk meat, she sells out. She typically charges $16.98 for a pound of grind. New York steaks go for about $34 a pound, and tenderloins $40 a pound. Molenaar knows it’s expensive, but she sells out within three weeks every year.

The big global competitor for elk is New Zealand, Cummons says. They’re able to raise a large amount of elk and red deer, so when one orders an elk steak at a restaurant, it’s likely from there. “It’s really hard to compete with them supply-wise,” Cummons says. “We don’t have enough to sustain U.S. demand. We just don’t.”

So What’s in the Way?

Molenaar says that a big barrier to entry to growing the elk industry, no matter how strong prices are now, is cost. For example, game fencing is different from typical fences. It’s eight feet high because an elk can generally jump about seven feet alone, and consists of squares. It’s about $500 for a roll of 330 yards. Ranchers also need to have substantial acreage for the animals to graze, but the rate of land per animal is actually quite similar to cattle: Both elk and cattle need about one acre per animal.

In Michigan, Northrup says that the regulatory mechanisms can add up, though they’re not entirely prohibitive. The license for the facility is about $770 every three years, and medical testing for chronic wasting disease across the whole herd is about $3,000 every three years. An annual inspection costs about $600, and any elk transported out of state costs $500 for a veterinary visit.

Part of the barrier to more growth in the industry could very well be the same thing that makes the price per pound so astronomical: It’s niche. People don’t really consider raising elk when compared to other proteins, and people that don’t eat elk may not have an easy way to try it. Molenaar doesn’t see the industry exactly dropping its velvet any time soon.

“It’s kind of stagnant … Information doesn’t get out,” she says. “Unfortunately I don’t think it’s an industry that will thrive, which is too bad. It’s rewarding.”

Cummons is more optimistic.

“I think [the field] is going to grow still. I really do,” she says. She’s involved with the North American Elk Breeders Association, and sees new faces at every meeting. The late 1990s may have been booming, but she thinks it’s coming back. “We have the potential to get there.”