In California, grassroots groups of researchers, growers, and volunteers are using mushrooms to clean up after wildfires.

In the first few weeks after deadly wildfires swept through the Los Angeles area in January, Mia and Justin Nguyen weren’t sure what they could do to help.

The couple runs a gourmet mushroom farm in Long Beach, California, which started as a pandemic-era hobby and eventually grew into an operation supplying 1,000 pounds per week to dozens of restaurants and farmer’s markets. All those mushrooms produced thousands of pounds of substrate — wood chips containing mycelium, the part of the mushroom that grows underground and is left over after the edible parts are harvested.

People had been coming to pick up spent substrate “by the truckload,” Mia Nguyen said, to use for composting or as a soil amendment, since the Nguyens began giving it to their neighbors for free in 2021. But after the fires, they noticed more and more people making the trek from Altadena, a community which had experienced widespread destruction, about an hour’s drive north of Long Beach.

“We heard the same story, that the land is in major need of repair and that many people are using the power of ... spent substrate,” Mia Nguyen told Offrange.

That material was used to help restore the soil in private homes as well as public spaces like the Altadena Community Garden, which had been contaminated with toxic heavy metals, plastics, and compounds like PCBs. In doing so, mushroom growers and the volunteers who use and apply their substrate are providing real-world data on the effectiveness of using mushrooms to clean up pollution, helping researchers understand how it can be applied on a larger scale in the future.

Known as mycoremediation, this technique is growing more popular as people search for low-cost, low-tech solutions in the wake of worsening natural disasters, driven largely by climate change. When a fire sweeps through a neighborhood like Altadena, all the plastics, electronics, and building materials it consumes release their toxins into the air and surrounding soil.

“We heard the same story, that the land is in major need of repair and that many people are using the power of ... spent substrate.”

While government agencies like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conduct a basic cleanup, that often just means removing the top six inches of earth and debris, leaving residents to deal with any remaining pollutants before they can safely rebuild. Recognizing that many people weren’t receiving the funding needed to carry out a full remediation — which can cost upwards of $100,000 — experts like Danielle Stevenson took matters into their own hands.

Stevenson, a researcher and founder of the nonprofit Centre for Applied Ecological Remediation, established the SoCal Post Fire Bioremediation Coalition, which brings together three organizations that use mushrooms alongside plants and other living organisms to help clean up after the wildfires. So far they’re working to demonstrate their technique on one plot of land in Altadena, though they’re hoping to get funding to expand to other sites this fall.

“We were seeing that there were a lot of groups forming that were interested in this stuff, but didn’t have experience” in the field, Stevenson said. “We wanted to offer guidance and expertise and build a coalition around this type of work, knowing that there will probably be more fires [in the future].”

Though this is the first large-scale effort of its kind in Southern California, other teams of growers and mycologists have previously jumped into action after devastating wildfires in other parts of the state. Gourmet Mushrooms, Inc., a mushroom farm in Sonoma County, donated oyster mushroom substrate after the Tubbs Fire in 2017, which was used to cultivate mycelium in straw tubes called “wattles.”

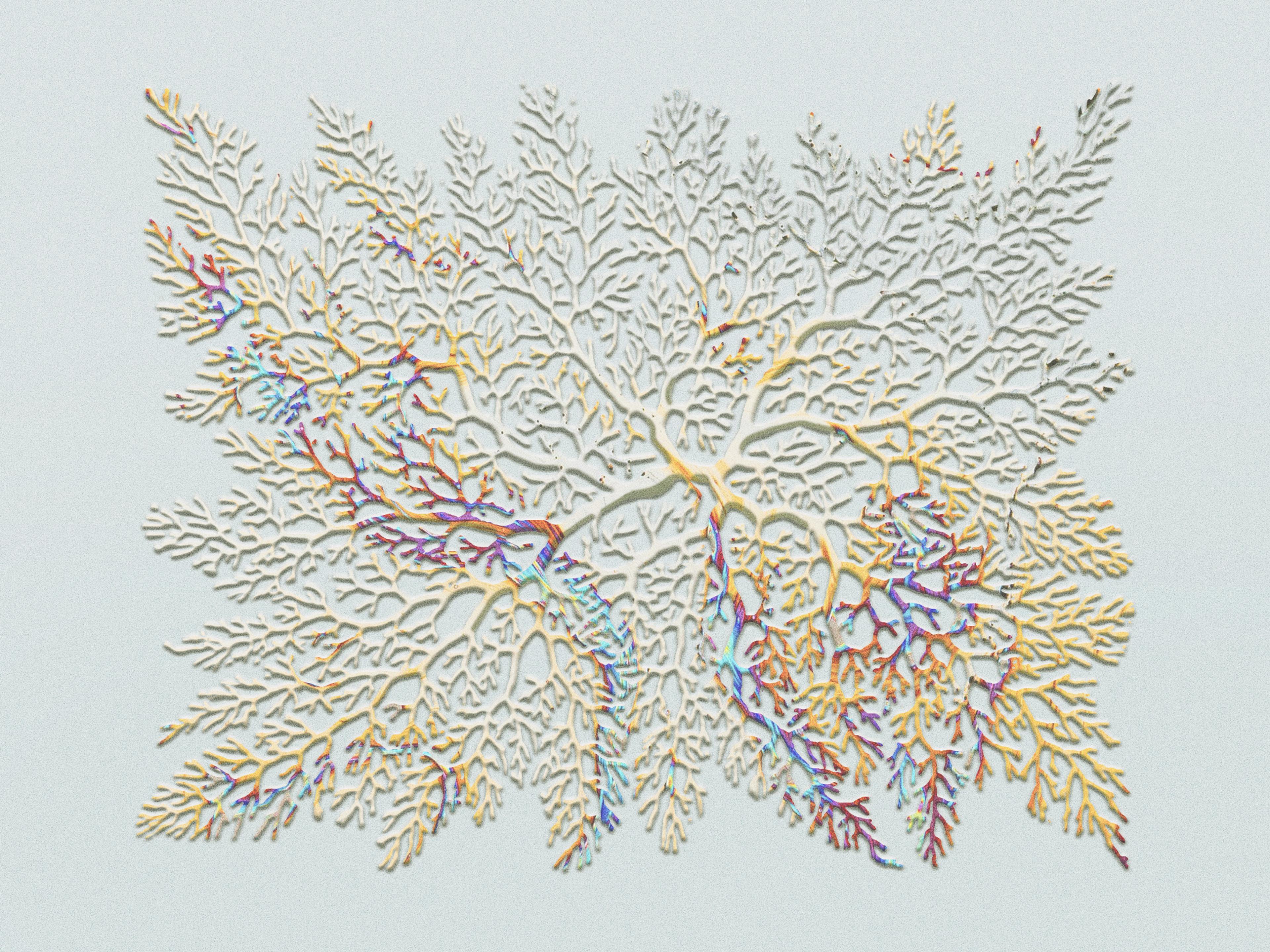

The process works because mushrooms release enzymes that can break down pollutants into smaller pieces, which they eat and absorb into their own tissue.

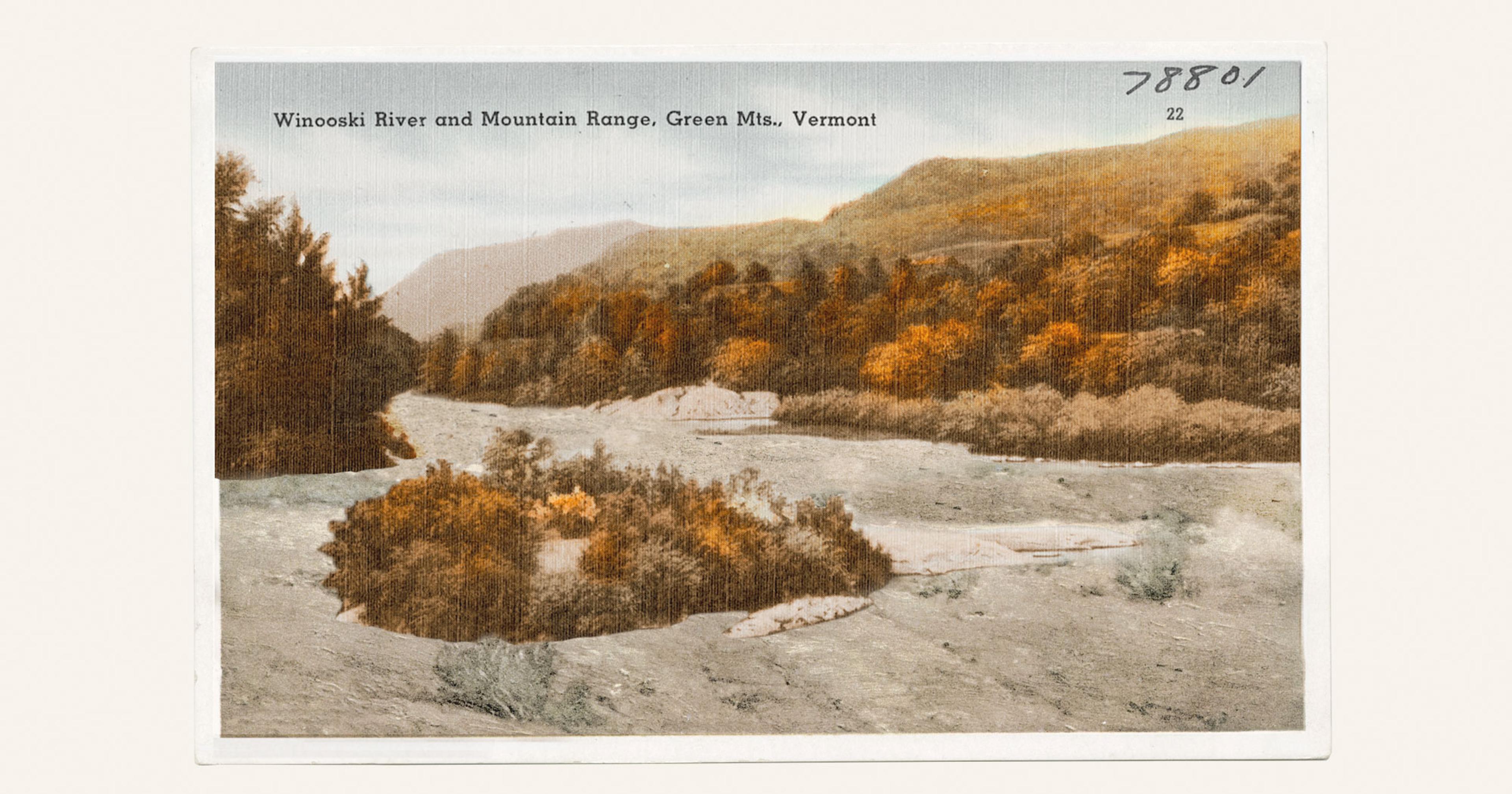

These not only provide fungi with a base from which to start breaking down toxins, but also help stabilize the soil, which is particularly vulnerable to erosion from wind and rain following wildfires. An organization called CoRenewal, which is also part of the SoCal Post Fire Bioremediation Coalition, led similar efforts in the Santa Cruz area following the state’s worst-ever wildfire season in 2020, with help from local mushroom farms Far-West Fungi and Mazu Mushrooms.

And in remote Butte County, California, where the Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise in 2018, a mushroom grower whose entire farm burned down began using his mycological know-how to introduce residents to mycoremediation. Cheetah Tchudi founded the nonprofit Butte Remediation to apply the technique on the ground and help people who had been left behind by the state’s cleanup process. Although he warned that mycoremediation is not a “silver bullet” — for example, the mushrooms proved less effective against heavy metals than other toxins — Tchudi believes they can be helpful when combined with erosion control measures like wattles.

“We could potentially use fungi as a biological barrier — a stopgap for these contaminants slipping into the watershed where they’re so much harder to remove,” Tchudi told Offrange. “Their ability to break down hydrocarbons can potentially reduce the toxicity of the ash while we’re waiting for it to get cleaned up. It’s what I call an imperfect solution to an impossible problem.”

The process works because mushrooms release enzymes that can break down pollutants into smaller pieces, which they eat and absorb into their own tissue. Along with these species, known as “decomposer mushrooms,” Stevenson also uses mycorrhizal fungi, which live symbiotically with plants and help them absorb heavy metals such as lead and arsenic. She focuses on stimulating fungi already present in the soil along with introducing other kinds of mushrooms, such as oyster.

“It’s what I call an imperfect solution to an impossible problem.”

Working in other contaminated sites known as “brownfields,” Stevenson had previously figured out the best combinations of fungi and plants to use for soils specifically in the Los Angeles area — knowledge that proved useful after January’s fires. It’s particularly important to avoid using non-native species for mycoremediation, Stevenson said, because they can become invasive; not all types of mushrooms commonly grown for food can be used for post-fire cleanup for this reason. “You wouldn’t want to use yellow oyster or any of the tropical oysters,” Stevenson said.

Stevenson is now conducting more research in Altadena to understand which species can be the most useful for wildfire cleanup specifically, and how to work with them. But the SoCal Post Fire Remediation Coalition is also pushing for these methods to be applied in real time, offering workshops to train people in the technique. The group is also actively seeking volunteers to help out with planting and caring for the sites, or producers who can donate seeds, tools, or compost.

Cleanup in Altadena is proceeding slowly, with homeowners fighting for insurance payouts and federal agencies declining to help with soil testing. Though a still-developing field, bioremediation offers an immediate solution that’s four to eight times cheaper than traditional cleanup methods, according to Stevenson. And farmers, gardeners, or people with agricultural experience can be particularly well-suited for it.

“[Bioremediation] takes similar types of skills,” Stevenson said. “You’re farming, but it’s a special type of farming.”