In building a foundation for the future, tree crop cooperatives are taking a patient approach to agricultural sustainability. It all starts with chestnuts.

The barn doesn’t look like much yet. The white exterior still bears the name of its former owners, the Atwaters, who once packed it with seed potatoes. The dusty interior has been stripped down enough to reveal a timber frame that dates, in part, to the 18th century. In the early days of summer, just shy of the Vermont border in Salem, New York, there’s little more inside than roosting pigeons and 6,000 square feet of empty ground on which to build.

But two years from now — or sooner, if Russell Wallack has his way — this will become the largest chestnut processing facility in the country. With help from a $2 million U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) grant targeting the development of new organic markets, Wallack and his colleagues at Breadtree Farms are converting the barn, aiming to turn it into a regional hub for growers to ready their chestnuts for sale. Their vision is aligned with a growing movement of farmers and gatherers leaning on cooperative models to overcome the prohibitive costs associated with processing chestnuts and other tree nuts as their markets materialize in the eastern United States.

The ambitious goal is nothing short of reimagining woodland landscapes as a source of abundance — a haven for perennial, climate-friendly foods that can feed local communities and offer opportunity to farmers looking to break free from the corn-and-soy paradigm.

“Chestnuts are the tentpole of everything we hope to accomplish,” Wallack says.

Among several crops attracting renewed interest from farmers focused on regenerative agriculture systems, the chestnut stands tall. It offers potential as a sweet, starchy carbohydrate with a nutritional composition similar to corn and other annual grains but a vastly superior environmental profile. It can be eaten fresh or ground into flour to make polenta, bread, and necci, an ancient Italian cross between a crepe and a tortilla. It also has a global market surpassing $5 billion, according to the Savanna Institute, an agroforestry nonprofit, and a long history as an everyday food in this country — one that was interrupted by a 20th century blight that killed billions of trees.

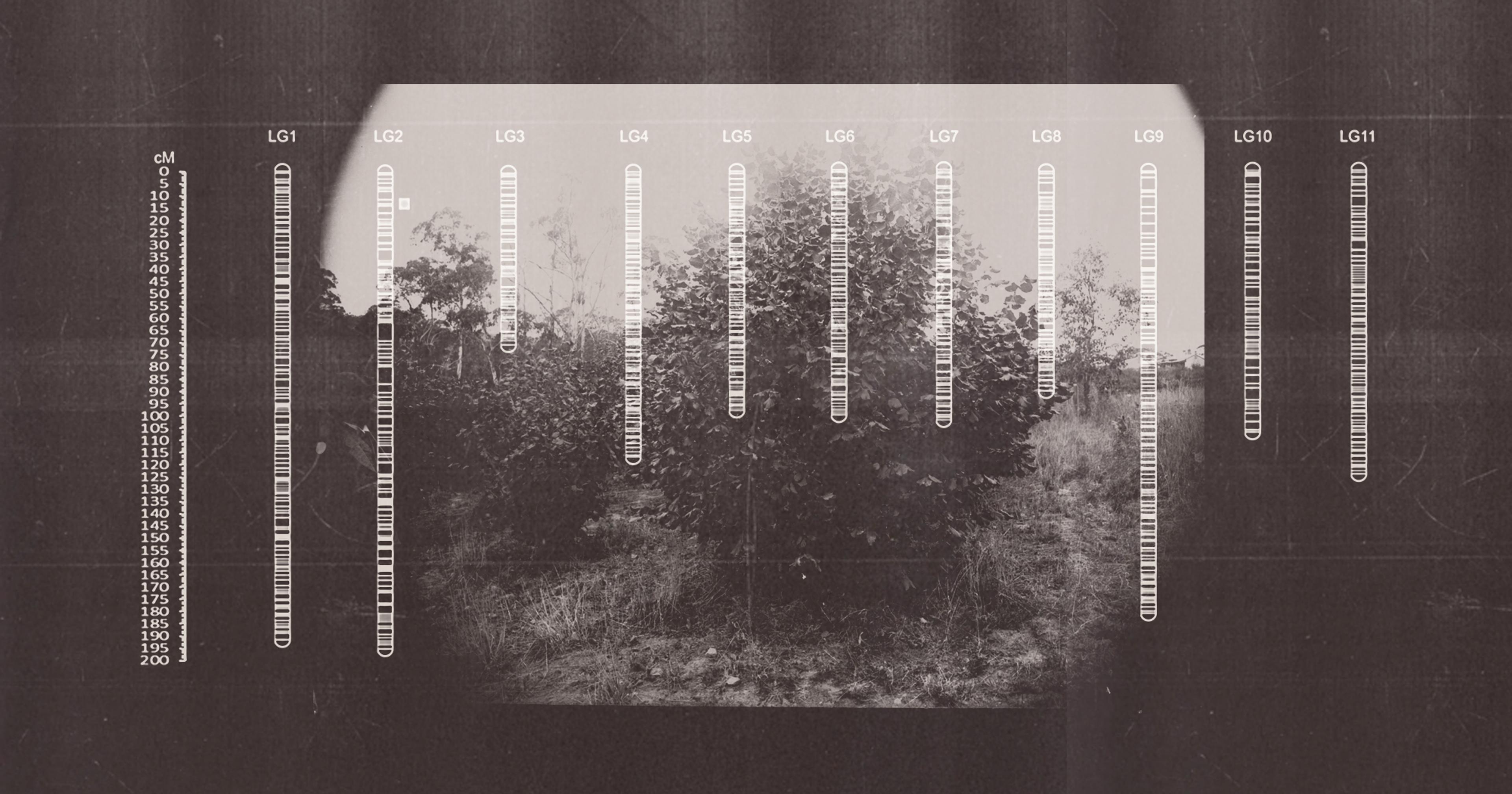

Biologists, conservationists, and environmental activists are working to bring the iconic American chestnut — distinct from the chestnut trees at Breadtree — back to its native range, which spans most of the eastern U.S., including much of New York. The American Chestnut Foundation, founded in 1983, uses plant breeding and genetic engineering to develop disease-resistant, genetically diverse chestnuts with the goal of wide-scale restoration to the landscape.

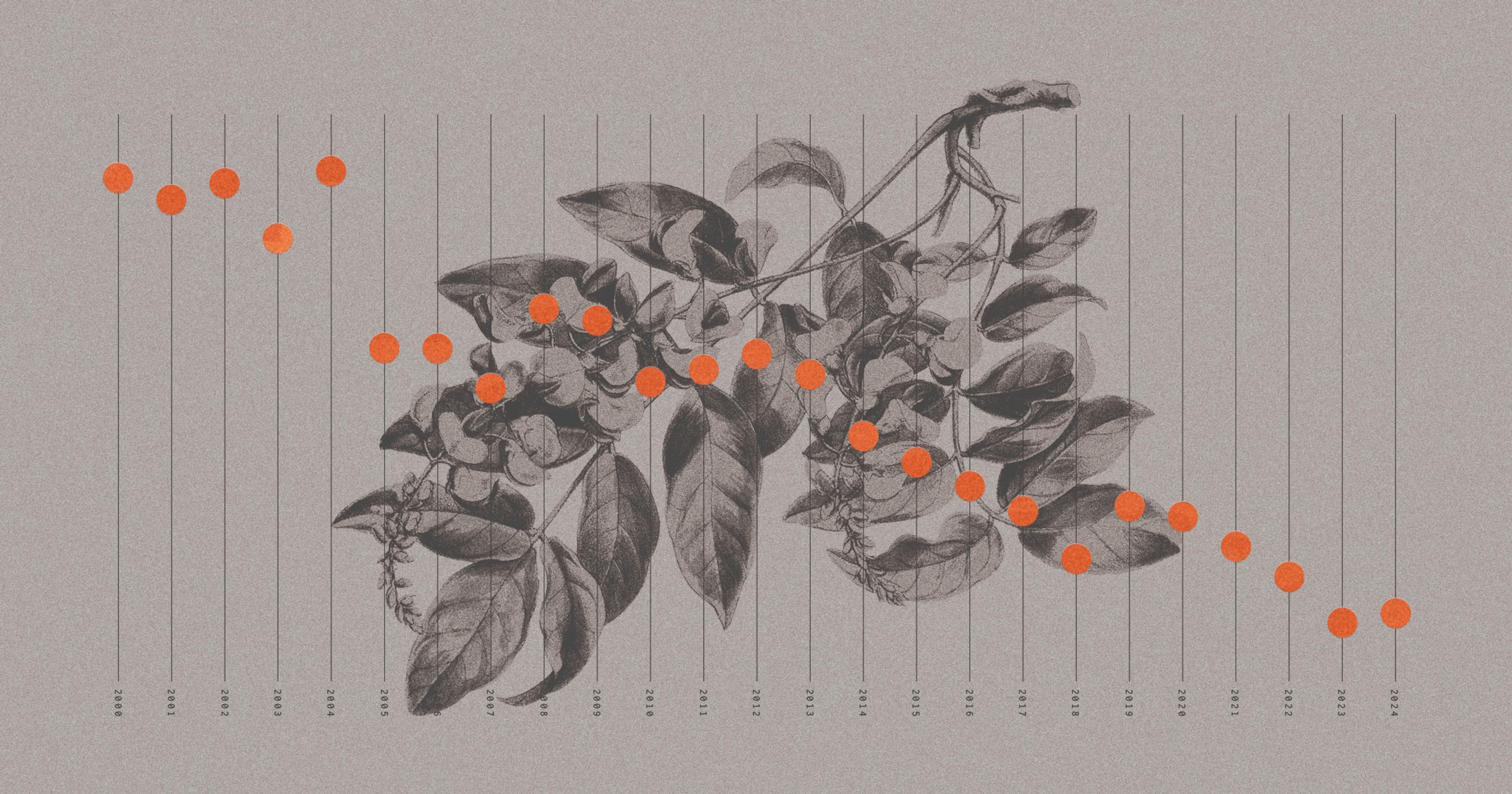

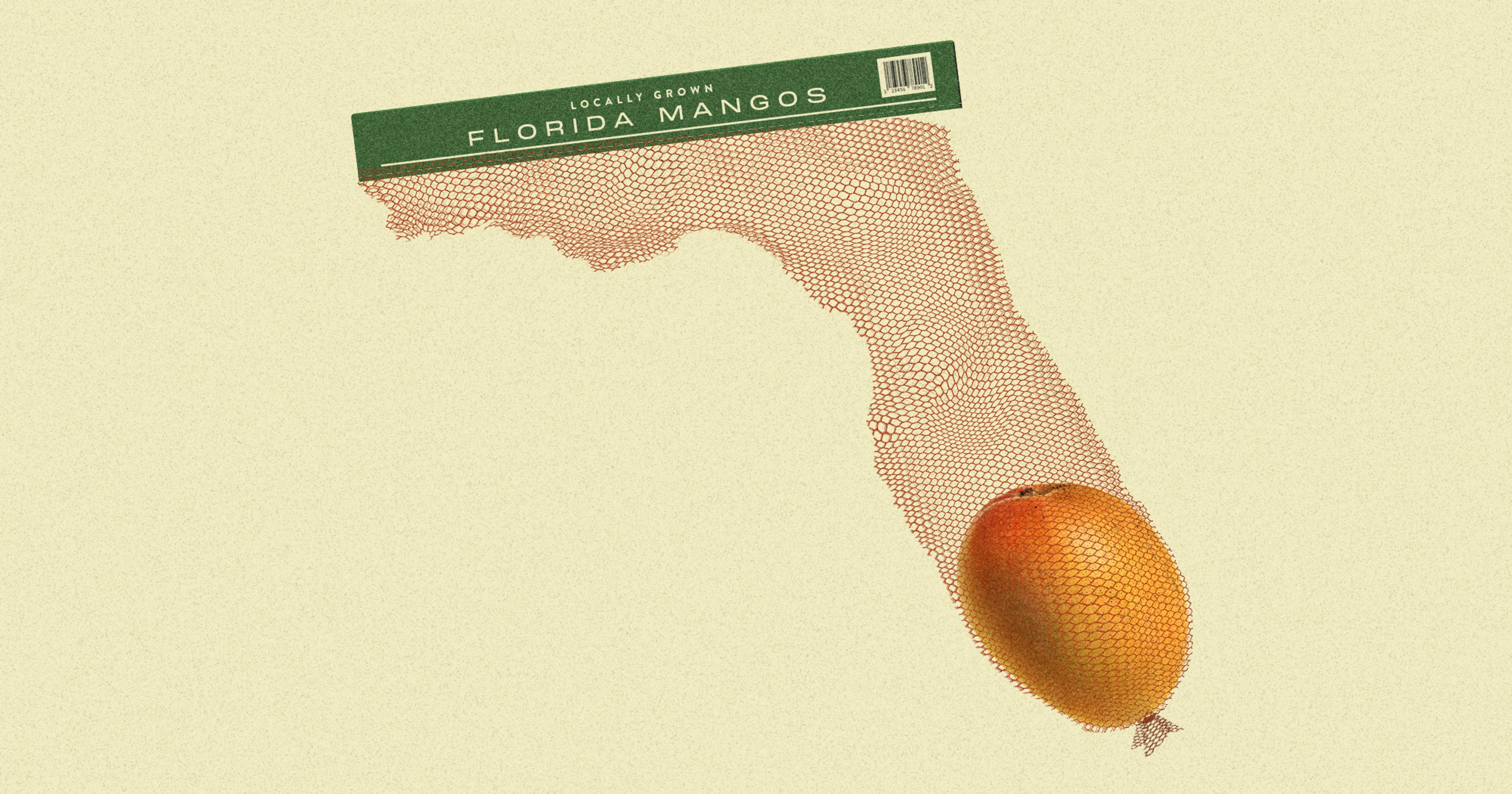

With that work in the background, Breadtree is hoping to revive the chestnut’s standing among American farmers and consumers. When the native chestnuts died off, so did the culture that had grown around them; the average American now eats a paltry 0.1 pounds each year, compared with one pound in Europe and four in Korea. China, whose own native species never suffered the fate of the American chestnut, dominates the global market, producing more than 80 percent of the world’s crop. Most of the roughly 3,000 tons the U.S. imports, meanwhile, comes from Italy. Breadtree wants to build a domestic alternative, using trees that include a mix of Chinese, Japanese, European, and American genetics.

Ripe chestnuts emerging from the burr at Breadtree Farms.

·Breadtree Farms

Doing so will only be possible with the right equipment and the right partners — and a surge in consumer interest. Breadtree aims to bring all three to its region, joining others who are laying the groundwork for an approach to agriculture that they believe can be both environmentally and economically sustainable. Although the farm isn’t organized as a cooperative, the facility it’s building will be spacious enough to handle 10 times the quantity of nuts it expects to produce on its own land. By providing a reliable place for processing, Wallack and his team want to encourage other growers to plant their own nuts, so they can expand the industry together. And expansion is possible, according to the Savanna Institute, which estimates a market opportunity of around 120,000 acres in the U.S., about 30 times the current size.

From New York and Pennsylvania to Ohio and North Carolina, growers and gatherers have established small cooperatives with a similar ethos in mind. Whether the focus is chestnuts, black walnuts, acorns, or hickory nuts, the easiest way to move forward is collaboratively, given the tens of thousands of dollars in crackers, sorters, mills, and presses — not to mention land — necessary to operate at any kind of scale.

It will take more than just motivation to turn tree nuts like these into the staple crops their backers believe they can be. In working to develop the supply chain, “the missing link is processing,” says Matt Grason, a member of Pennsylvania’s Keystone Tree Crops Cooperative, which last year produced its first modest run of hickory oil — 70 bottles’ worth.

Inside its repurposed barn, Breadtree is building that missing link.

Until 2019, Wallack, who has a master’s in ecological design from The Conway School in Western Massachusetts, was a consultant to food companies and landowners, whom he regularly implored to plant chestnuts as an environmentally sound investment for the future. He wanted to see hundreds of acres of trees spread across New England, bearing two to three thousand pounds of nutritious, profitable chestnuts per acre, year after year. But he soon realized urging others to buy in “wasn’t a strong theory of change,” so he started searching for land where he could help prove the viability of a farming system that shared his principles.

Wallack scoured the Northeast for a landowner willing to enter a long-term lease. Trees typically begin bearing nuts after about five years and don’t reach maturity for 15 or 20; Wallack estimates the break-even point on an investment at 10 to 12, provided a grower has what they need for processing. With that in mind, he eventually found a recently retired fifth-generation dairy farmer who was open to a 30-year agreement. With help from family and friends, he planted Breadtree’s first 800 chestnuts in the spring and summer of 2019, acquired at a discount after someone else bailed on their purchase.

“This is something that’s good for the planet, good for the grower, and good for the consumer. The constraint is you have to make money or it’ll never happen.”

Since then, Breadtree has used around $2 million from investors to expand its operation to several sites spanning 600 acres, mostly in Washington County, New York, nearly half of which is occupied by orchards and silvopasture. Around 85 acres will bear some quantity of nuts this fall, already surpassing the country’s total for organic chestnuts, Wallack says. Hundreds more young trees dot Breadtree’s properties, still sheltered in white tubes. Soon, they will join the fray, and the harvest will grow exponentially.

Considering the present scale of Breadtree’s operation — last year’s crop was about 1,000 pounds and this year should double it — the equipment needed for processing remains minimal. Even meeting Breadtree’s own needs several years down the line would only have required a facility capable of handling 50,000 to 100,000 pounds a year.

But the USDA’s backing will allow the farm to build a million-pound processing facility that dwarfs any other in the country, complete with a pass-through for nuts delivered from around the region, where more than 150 current or aspiring growers have already expressed interest in partnering with the farm. The grant is also supporting outreach, education, and product development to broaden the chestnut’s market — a pivotal, if uncertain, part of the vision — as well as a feasibility study to guide others in building something similar. A tour of processing facilities in Italy, where the chestnut is so engrained that some simply refer to it as “the tree,” informed the farm’s preparations.

Wallack considers chestnuts “a foot in the door” for a broader vision of agroforestry, a “somewhat bankable” way to begin establishing landscapes that can yield a range of tree crops and products including acorn flour and hickory oil. For Noah Simon, who started planting trees with Wallack in 2020 and soon became a partner in the farm, their work is focused on facilitating a better future for a generation of farmers who “don’t really have a good menu of viable perennial agriculture” that makes sense economically. He points to Organic Valley, the Wisconsin-based dairy and produce cooperative owned by more than 1,600 farms, as a model for what Breadtree wants to build. Organic Valley, of course, sells a range of popular dairy products that don’t need any help with market development.

“I hope that over the next 10 to 15 years, with partners, we can help to develop many of those missing pieces as steps towards a cooperative industry where people can do this work and do it together,” Simon says, “so it can actually impact the food system and not just be a marginal, niche thing.”

An educational tour of Breadtree Farms' silvopasture at its Otter Creek Farms, where chestnuts planted in 2019 are grown alongside beef cattle and honeybees.

·Breadtree Farms

Bug Nichols, who began planting with Breadtree as a volunteer in 2020 and later became its first employee, says she and her colleagues are under no false pretenses about their certainty of success.

“Our business could fail,” she says. “But all of us think that even if our business did fail, it would have been helping take another step toward trying out new ways of farming in our region.”

Breadtree’s seemingly niche idea is based on millennia of history in which chestnuts and other tree crops fed people in New York and other places where they were grown. Restoring that approach to agriculture and reaping the environmental benefits — carbon sequestration, abundant wildlife habitat, improved soil health and water quality — will require cooperation and collaboration across a developing industry, as well as an openness to long-term thinking. It takes patience, but patience is the path to a healthier and more sustainable food system.

“Until there are people who want to finance agriculture on a decade timescale, we won’t have agriculture that works on a century timescale,” Wallack says.

Greg Miller has several decades invested in his chestnuts in Carrollton, Ohio, an hour southeast of Akron. His father began planting them in 1957 and kept them as a hobby until the ’80s, when Miller started Empire Chestnut Co. with several hundred trees already bearing. In the early 2000s he began marketing the nuts grown by three of his neighbors, who joined him in establishing the Route 9 Cooperative in 2009 after a bumper crop delivered 60,000 pounds — well more than Miller could handle. The co-op’s members invested about $180,000 into a 5,000 square foot steel-framed facility on Miller’s property and have been in business together ever since, now selling around 100,000 pounds of fresh nuts in the shell every year.

It costs about $2 per pound to grow Route 9’s chestnuts, which wholesale for $4 to $5 and wholesale at twice that, Miller says. Margins go up in concert with volume, so operating as a cooperative is a boon for members. It helps that demand outstrips supply, particularly among immigrants whose home countries retain a strong chestnut culture. In 1994 a Korean couple backed their truck up to Miller’s door and asked to buy his entire crop, he says. Business hasn’t slowed since.

“Once people find out that we have them, they clamor to get them,” Miller says.

Beyond the economic benefits of the cooperative model, Miller has found that a collaborative spirit helps move the operation forward. Periodical meetings allow farmers to learn from one another, sharing knowledge about growing and harvesting methods and proposing new ideas for how to best run the business. There’s something to be said for not having to go it alone, he says.

“I hope that over the next 10 to 15 years, we can help to develop many of those missing pieces as steps towards a cooperative industry.“

To that end, Miller has spent years serving as mentor for chestnut farmers and hobbyists, including the farmers at Breadtree and others establishing co-ops. During the busiest weekend of the annual harvest, in early October, Route 9 hosts what Miller has dubbed “Chestnut Woodstock,” inviting as many as 50 people to camp in the orchard, help out with the harvest and learn about the ins and outs of growing nuts. At the end of it all, he delivers what his daughter, Amy, calls his “chestnut sermon,” a treatise on the philosophy behind shifting from annual grain production to perennial tree crops. Anybody who fairly examines annual agriculture will conclude that “it’s just not a sustainable practice,” Miller says. Chestnuts and other tree crops, though, can be.

“This is something that’s good for the planet, good for the grower, and good for the consumer,” Miller, now 70, says. “The constraint is you have to make money or it’ll never happen.”

Cooperatives offer an answer to that conundrum, as Justin Holt and his colleagues at North Carolina’s Asheville Nuttery have found. Since 2017, the cooperative has been wild harvesting black walnuts, bitternut hickory and acorns, as well as buying them from community members. A separate but related cooperative called the Nutty Buddy Collective manages two four-acre orchards set up with 99-year leases signed in exchange for a share of their eventual yields.

The Nuttery processes its nuts in a facility stocked with equipment amassed through Kickstarter funding and a secondhand purchase from an Ohio grower. (That grower, Kurt Belser, explored nut crop production with a USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant and determined it can be economically viable as long as farmers band together.) Last year, the co-op started selling holiday boxes stuffed with a dozen products, including fresh nuts, oils, acorn cookies, and black walnut salad dressing.

Like many growers, there’s something spiritual about Holt’s relationship with nuts. He still savors his first encounter with a hickory nut, cracking it open as the aroma of banana nut bread wafted out. “It was dizzying. It went straight to my heart,” he says. “It was like I saw God in some way.”

“All of us think that even if our business did fail, it would have been helping take another step toward trying out new ways of farming in our region.”

Holt believes growing tree nuts can help address “the deleterious effects our diets have on us and our planet,” and he sees how compelling the notion can be for like-minded individuals. “The foods themselves are interesting and delicious and expand our palates and what it means to eat from our places,” he says. “And there’s other levels to it: the need for togetherness, to feel like you’re part of something and that you’re contributing to a promising, hopeful vision for the future. There’s a hunger for that.”

But that doesn’t mean the work is easy, Holt admits. He’s spent the last decade wrapped up in the promise of it all, only to find himself burnt out from the uphill battle of changing even a small corner of the food system. For those willing to forge ahead, it’s only possible with partners.

“If anyone is actually willing to do it they come up against limitations real quick,” Holt says. “Land is impossibly expensive. There’s nowhere to process. You’ve got to figure this all out on your own. That’s the reason people turn to cooperative approaches. How can we get together and figure out how to do this?”

At Keystone, Grason and about a dozen fellow members bring a similar communal approach to nut harvesting. They’re focused on hickory oil but also plan to buy chestnuts, hazelnuts, and black walnuts to turn into value-added products, aiming to develop the market for tree crops with support from a Climate-Smart Commodities grant that delivered around $50,000 before being frozen by the Trump administration. (Breadtree’s USDA grant was also temporarily frozen before being reinstated; the pause will likely delay the facility’s opening by a year, shifting the goalpost to the 2027 harvest.)

The New York Tree Crops Alliance, meanwhile, shares Keystone’s vision, emphasizing hazelnuts and chestnuts, although member Brian Caldwell says Breadtree will serve as the region’s primary hub for the latter. There’s a sense of unity among those invested in seeing tree crops flourish, which feeds into the cooperative approach taking root, he says. “It self-selects for a certain kind of person,” he adds. The kind of person who sees an opportunity to reorient agriculture by establishing local economies based around perennial systems in places that currently produce relatively little of their own food — even if, as he acknowledges, growing demand alongside supply may be harder than growing the nuts themselves.

“It’s kind of like a fallow field,” Breadtree’s Simon says. “It’s fertile ground for something new to be done.”

When Breadtree’s farmers visited Italy’s chestnut region last fall, they witnessed what it could look like to achieve what they’ve set out to do. Nichols recalls walking through orchards that have been stewarded by families for centuries, their trees producing nuts in a seemingly endless cycle. Working with tree crops encourages people to consider their work from a generational perspective, she says, and the only way to do that is in community with others.

As Holt says of the tree crops movement, “the long-term vision is something on the time scale of an oak tree.”

It seems fitting, then, that Breadtree is pinning its future on a barn that has stood the test of time. Adaptive reuse is a complex proposition, Simon admits, “but it’s also part of our heritage.” Demolition began last winter, clearing off inches of dust and debris that had accumulated over nearly a decade of disuse and breaking down the interior so it can be built back up. Along the way, Breadtree will continue leaning on the wisdom of their compatriots. Miller, the Route 9 veteran, says that’s the only way to proceed. Work with tree crops moves too slowly for anyone to answer all the questions that arise in one lifetime, so collaboration is essential.

“Nobody can do this on their own,” he says.