In a drought-stricken world, recycling our wastewater could help put food on your plate.

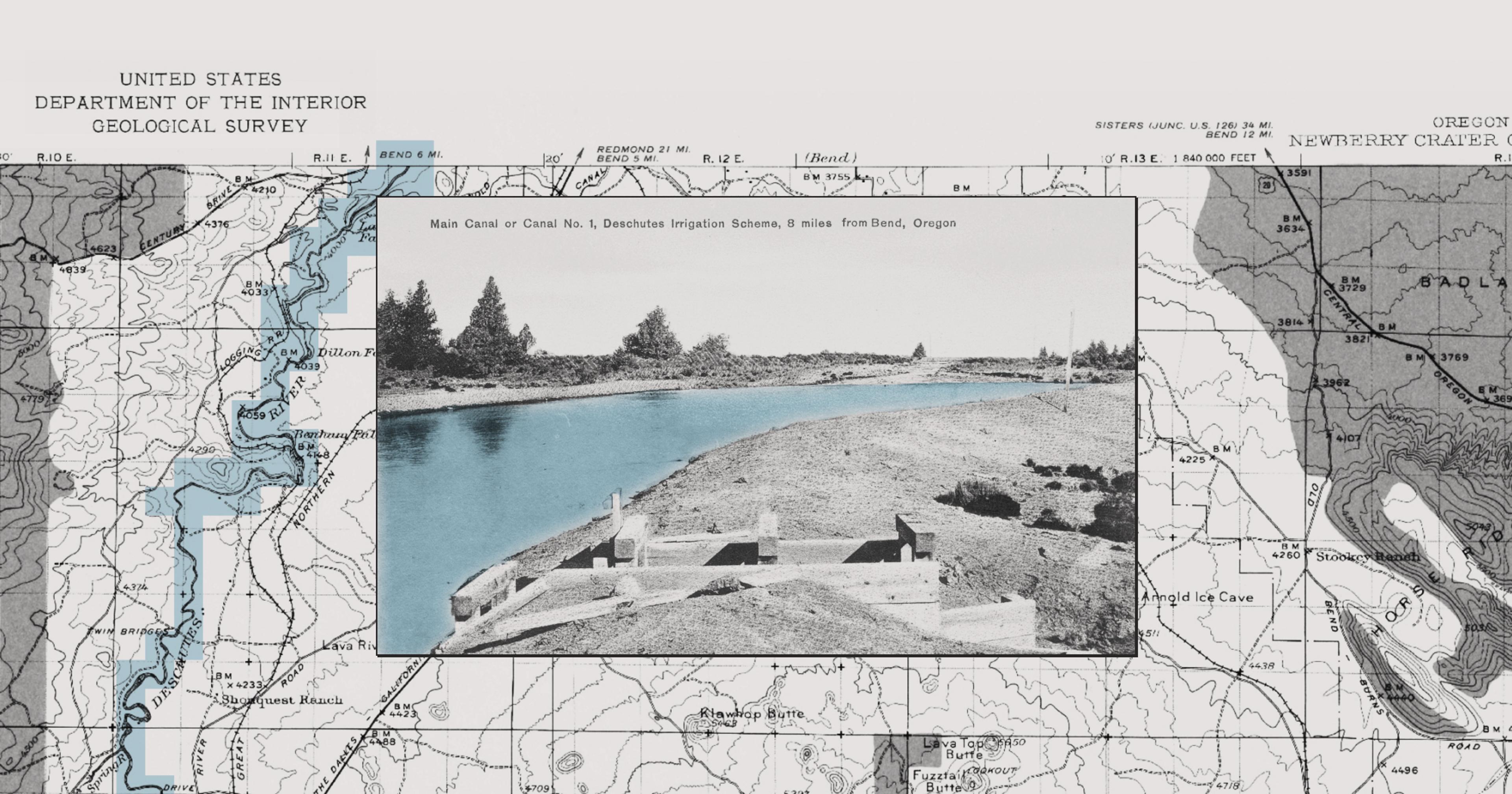

The concept of using toilet water to irrigate crops isn’t new: California has been recycling wastewater for more than 100 years. But the demand for such water is growing in the U.S., as long stretches of drought — which scientists predict will continue to be exacerbated by climate change — drag on.

Not only are Western states parched, but normally water-flush ones, like those in the mid-Atlantic, are also experiencing water issues. New Jersey, where I live, had one of the driest Mays on record this year — a problem for the “garden” in the Garden State.

Ensuring there’s enough water to safely irrigate crops has become a pressing agricultural need, especially as federal money flows into water-related infrastructure projects. In a time of intensifying drought, re-using both the water and nutrient content otherwise flushed down the toilet could become bigger parts of meeting our agricultural needs.

Rethinking Toilet Water in a Drought

We send a lot of clean water through our toilets in the U.S. They are the main source of water use in the average American home, making up 30% percent of our indoor water consumption, according to the EPA.

Modern sewage systems were set up to be water-intensive, for the sake of sanitation. Before indoor plumbing became the standard in the U.S., things like hookworm, typhoid, and dysentery were routine problems. Clean, sparkling toilets, with plenty of water to flush our effluent away, were a win for public health.

“You have this system designed to just throw the water away in most places,” said Chelsea Wald, author of Pipe Dreams: The Urgent Global Quest to Transform the Toilet.

Dedicating so much water to flushing (and it’s still a lot, even after a 1992 ruling that reduced toilet capacity from about 3.5 gallons to 1.6 gallons per flush) has increasingly become a problem in a climate-changed world. The Colorado River, which provides drinking water to 40 million people and supports a $15 billion agriculture industry, is drying up. In May, the government of Arizona announced that it would begin to limit construction in the Phoenix area because there’s already not enough groundwater to support projects already approved. While flushing toilets is far from the only reason for these water crises, they certainly don’t help.

“We’re seeing groundwater depletion creep up the East Coast, which will eventually challenge farmers on their water needs.”

Other parched areas of the world have already embraced recycled water. In Israel, for example, 90% of the wastewater is reused, most of it in agriculture. In Tunisia, which the World Health Organization says is one of the most water-scarce countries in the world, a $60.6 million wastewater recycling facility is treating wastewater to be used on crops while keeping untreated sewage from polluting the Mediterranean Sea. In 2020, for the first time in years, its Raoued Beach was deemed healthy enough that it was opened back up for swimming.

For farmers, water scarcity means their wells might be going dry and, for those on the coast, seawater intruding into those wells. Salt can poison crops, thus making those wells unusable. “It’s the reality. It’s why more farmers have accepted it,” said Marcus Mendiola, water conservationist and outreach expert at the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency (PVWMA), about the wastewater they’ve been recycling in partnership with the city of Watsonville, Calif., since 2006.

The PVWMA facility provides recycled wastewater to farmers in two counties, where the agriculture value tops $1 billion, according to Mendiola.

Well water has traditionally been cheaper than piping in water from a facility like PVWMA’s, but times are changing, “More of their wells have been intruded from seawater in the past 10 to 15 years. They need an alternative or it becomes exceedingly challenging to farm along the Central Coast,” said Mendiola. That’s also helped farmers who might have once said they didn’t like the idea of using water that had once been in a toilet. Until recently, the “ew‘’ factor was still too strong.

“We have to get over the notion that the way we’re doing things is the right way to do it.”

Their facility can recycle about 6 million gallons of wastewater every day, with about 5,000 acres per feet delivered in a three-county water zone, which still only meets about half the demand in the area where PVWMA could deliver water.

Regulations about using recycled wastewater are handled at the state level, with EPA playing a supporting role through their water reuse program. Twenty-eight states have water use regulations or guidelines for agriculture, but not all allow it on crops grown for humans to eat. Pressure for water is also mounting for farmers in other parts of the U.S., including states like Delaware, Rhode Island, and Georgia, that currently allow recycled wastewater to be used in some capacity for irrigation. This includes feed crops for animals, but not on food crops for people.

“There really hasn’t been a need for farmers to worry about their supply,” in these areas of the country, said Patricia Sinicropi, executive director of the WaterReuse Association, a trade group of utility companies and businesses that support the use of recycled water and recycled water projects. “That will change because we’re seeing groundwater depletion issues creep up along the East Coast, which will eventually challenge farmers on their water needs.”

Setting up systems that can treat wastewater and convert it into irrigation water aren’t built overnight. To help, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law directed $50 billion to the EPA to improve drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure — the agency is currently working with state and local governments to connect their projects to that funding.

Waste Not, Want Not

There is also a movement to stop being so wasteful with our water flushing, not to just save that water, but also to recycle nutrients from our waste and turn them into something useful — instead of being flushed out and polluting bodies of water.

Doing so is relatively simple in a closed environment, said Wald, who has also covered this topic for Nature. “Urine has few pathogens, and doesn’t need to be as carefully managed” as feces, she said. Pharmaceuticals may come out in our urine, but they’re too diluted to be a concern, per the USDA. That’s why it’s a no-brainer for urine in a hyper-controlled environment, like the International Space Station, to be recycled into water again.

But when urine is flushed away, it’s then mixed in with everything else in the water, including feces, wipes, and household and industrial chemicals. That makes the extraction of those nutrients to be turned into something useful (like fertilizer) much harder.

Strides have been made towards figuring this out, including innovations like waterless urinals and urine-diverting toilets, which direct urine just about exclusively where it needs to go. But they’ve been small — a proverbial drop in the toilet bowl. To do this on a massive scale would take entirely rethinking how we handle our effluent, said Wald, which would also be costly to implement. Even as investments are being directed toward addressing aging sewer and water infrastructure in the U.S., that’s to fix what we have — not rip out and replace the whole thing.

It’s one of the reasons her book is called Pipe Dreams, emphasis on the “dreams” part. “It’s a really big lift. We just have to get over the notion that the way we’re doing things is the right way to do it,” she said. Public sewer systems have been a massive benefit to public health, “and thank goodness for them,” she said. But, at the same time, “We have to let in the idea that there’s a better way to do things.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story said the PVWMA facility provided recycled wastewater to farmers in three counties,