In the wake of the 2021 ransomware hack of agribusiness giant JBS, what lessons have we learned?

A decade ago, ransomware and food were two words that one might not think to link.

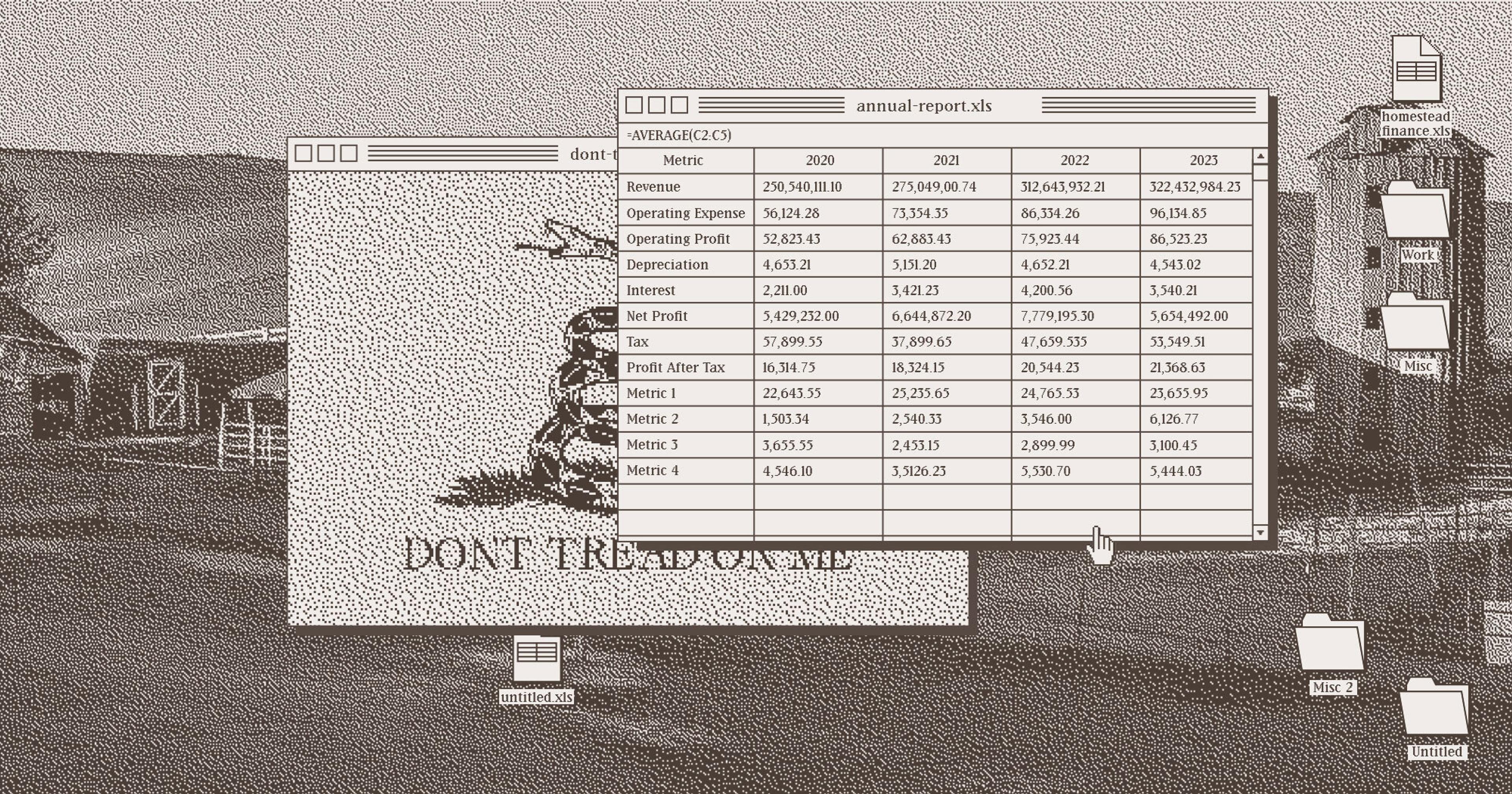

That was before May 30, 2021, when JBS, one of the world’s biggest beef, pork and poultry producers, was held for an $11 million dollar ransom by REvil, an alleged Russian-based cyber gang.

The attack involved systems essential for the operations of three beef and pork plants in the U.S., Canada, and Australia, forcing them to temporarily shut down operations. Per a media statement released the next day, “The company took immediate action, suspending all affected systems, notifying authorities and activating the company’s global network of IT professionals and third-party experts to resolve the situation.”

To regain control, JBS made the tough call to make a payment. As in any ransom situation, this decision was heavily critiqued, due to concerns that meeting such demands could encourage future attacks. It remains the largest ransomware payout in the food and agriculture sector to date, but is far from the only example.

The same thing happened to two regional farm cooperatives in Iowa and another in Minnesota that year. And just last year Dole took a hit, losing $10.5 million in an attack that stole the Social Security numbers of nearly 4,000 employees. Containing the breach impacted half of their servers and several user-end computers, disrupting a portion of their fresh vegetable processing.

Agriculture and food are by no means digital newcomers. From data-driven farming with satellites and machine learning to packing house optimization software, large swaths of the supply chain operate on a technological plane. But this digital revolution comes with a hidden cost — an elevated risk of cyberattacks that threaten everything from enormous agribusinesses to smallholder farms.

Precision agriculture in particular presents a unique cybersecurity challenge. By integrating the internet into a traditionally mechanical and labor-intensive industry, it vastly expands the potential attack surface. This creates a scenario where common cyber threats can have amplified and far-reaching consequences compared to, say, the insurance or real estate industries.

For example, the privacy and security of farm data is a critical vulnerability. Farmers hold this information dear, as its loss or abuse could have severe consequences. Irreplaceable information, like herd health records, financial details, and field-specific metrics, is susceptible to theft, abuse, and illegal sales. And because so much ag activity is time-sensitive and season-bound, cybercrime that compromises essential data faces immense pressure to be resolved as quickly as possible.

Any delay could lead to supply chain disruptions or the loss of crops and commodities, not to mention the significant financial, emotional, and business harm that would follow.

“Just like adapting to changing weather patterns, small to large growers are going to take the lessons of JBS to heart.”

Farm suppliers and commodity brokers like co-ops which deal with highly sensitive member data carry the added risk of losing their reputations and rapport, as noted by the 2018 white paper Threats to Precision Agriculture by the Public-Private Analytic Exchange Program, produced in conjunction with multiple federal agencies.

“[P]ublic release of information such as confidential pricing and market data of farmers from a supplier, could have catastrophic impacts for the supplier as it would destroy trust and cause customer loss,” reads one section.

The ag industry’s reputation of using outdated, internet-connected legacy systems that often lack security controls has made a harvest ripe for cyber thieves. Worse still, many of their networks are unsegmented, meaning it’s very easy for hackers to gain access to multiple systems.

Kristin Demoranville has had a 24-year career in information security and information technology. She said food industries remain a soft target which is, frankly, “terrifying.” Demoranville, who founded her cybersecurity advisory consultancy firm, AnzenSage, in 2023, is one of a handful of experts specializing in security risk resistance for the food industry.

She observes that, generally, there is a lack of cybersecurity awareness and training for small to mid-sized producers. And on the flipside, the operational technology and industry control systems community aren’t very familiar with the nature of food and agriculture operations. “I am constantly dealing with disinformation and misinformation,” she said, referring to a lack of understanding on both sides.

Demoranville said that in her experience, many smaller food processors and agribusinesses don’t want to accrue the expense of implementing vital security measures. And even giants like JBS can still fall short. The vice president of cybersecurity firm BitSight, which conducted an audit of JBS, summarized their report in an email saying the company’s “overall rating was poor.” (Emails were obtained by the journalism outlet Investigate Midwest, through a FOIA request.) Another company, SecurityScore, found that “1 in 5 of the world’s food processing, production, and distribution companies rated have a known vulnerability in their exposed Internet assets.”

“People don’t get the connection between a cyber incident and their food on their plate. That’s the big problem.“

Thomas Siu, former chief information security officer for Michigan State University currently working at cybersecurity firm Inversion6, observed that food and agriculture, especially at the farm level, “is immature in the ability to resist cyberattacks.” Compared to other industries like banking or healthcare, he notes that even core data rarely has privacy considerations.

Still, he thinks the landmark JBS attack was a big wakeup call.

“The industry as a whole is versant in risk management,” he explained. “Just like adapting to changing weather patterns … small to large growers are going to take the lessons of JBS to heart.”

Part of the problem with food and ag cyberattacks is that the mainstream public doesn’t always recognize their impacts. In the JBS situation, for instance, Australians had a hard time finding beef in stores for some time. That said, Demoranville doesn’t think consumers necessarily made the leap that the scarcity was linked to the attack.

“People don’t get the connection between a cyber incident and their food on their plate,” she said. “That’s the big problem. How do you make someone care if they don’t understand it?”

Another issue is that critical operations systems, originally designed for internal use only, are ill-equipped to handle today’s security demands.

“[These systems] been attached to the internet — which they were never meant to because they didn’t even know the internet existed when those machines were made,” Demoranville said. “Now they are put [online] where there’s no security controls in place.”

“If hackers could falsify or corrupt crop and livestock health information to mimic a disease outbreak, the economic disruption could be catastrophic.”

Todd Janzen of Janzen Ag Law noted that the food and ag space has fewer legal protections in place as well. Many of the current laws in place are meant to protect personal information as opposed to agricultural data, he said. Additionally, investigators likely have less experience working in this space.

“I think in many instances, the criminals get away with it because it is very hard to track them down and prosecute them,” Janzen said. “Your typical state prosecutors are not necessarily set up to go after a lot of cybercrime.”

There may be help coming on the federal level with the The Farm and Food Cybersecurity Act, bipartisan legislation introduced this year in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Led by Representatives Brad Finstad (R-MN) and Elissa Slotkin (D-MI), the act is aimed at bolstering cybersecurity measures within food and agriculture’s critical infrastructure sector.

In an email statement, Rep. Slotkin said: “Food security is national security, so it’s critical that American agriculture is protected from these threats. We know that cyberattacks have the potential to upend folks‘ daily lives and threaten our food supply, just like we saw a couple years ago when the meat-packing company JBS was taken offline by a ransomware attack.”

The proposed legislation would also require the USDA and federal partners, alongside state, local, tribal and territorial governments, to conduct annual exercises that simulate food-related emergencies or disruptions. An exercise like this, called CyberStorm, was recently conducted with multiple government agencies and more than 2,000 food and agriculture stakeholders.

“In the food industry, it’s not just about the data. We’re safeguarding human lives.”

These preparations tie in to long-running concerns — which some have said are overblown — that our entire food supply is vulnerable to attacks from bad actors. Incidents like intentional release of a contagious livestock disease or a widespread poisoning event remain a vivid and much-discussed worry in many sectors of government. In the digital space, however, you wouldn’t need to carry out a real-world attack — a hacker could potentially falsify online data to make it seem like, say, a destructive disease is spreading.

“If hackers could falsify or corrupt crop and livestock health information to mimic a disease outbreak, the economic disruption could be catastrophic,” security consultant Mark Montgomery wrote in a Cipher Brief op-ed. “Farmers and health inspectors might need months to confirm whether or not there is indeed an outbreak. In the meantime, herds might be decimated, food prices would soar, and foreign trade would halt.”

While building a robust infrastructure with private entities and governmental support is important, there are other actions that agribusinesses can take to cover themselves if the worst happens. When a cyberattack strikes, Demoranville said swift and decisive action is critical. Businesses would be wise to engage cybersecurity experts to assist with containment, analyze the attack forensically, and guide the remediation process. They can also help devise protocols for how to respond in emergency events.

Ransomware incident response should include accessing the extent of data encryption and weighing recovery options such as restoring systems from backups, or even negotiating with attackers. This is a complex decision, and seeking expert advice is highly recommended. And once the dust settles, Demoranville advises a thorough post-incident review to understand what went wrong and identify areas for improvement.

“In the food industry, it’s not just about the data,” Demoranville stressed. “We’re safeguarding human lives.”