“Clean weed” farmers seek more sustainable — and profitable — approaches to cannabis production.

Like a toddler on a crisp fall morning, Brian Niestrath was getting excited about a big pile of leaves. He and his wife, Sarah, co-owners of the Southwest Oregon farm Green Bandit, were awaiting a mid-November dropoff from the nearby city of Eagle Point, where municipal workers had collected the bagged autumnal bounty from hundreds of homeowners.

“My favorite would be the maple leaves. They’re just very delicate and pretty, red and orange and all these radical colors,” Brian Niestrath enthused. “And then probably the best leaf is willow — that just seems to break down the fastest.”

The Niestraths planned to unbag this free organic material and mix it into their compost heap with feather and bone meal and alfalfa. From there, it would be applied to the fields and begin its transmutation into a very different kind of leaf: the slender-fingered green fronds of cannabis.

Because marijuana remains federally illegal, it’s ineligible for organic certification under the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But that hasn’t stopped growers from seeking to produce what they call “clean weed” with practices like cover cropping and on-farm composting. Third-party organizations like Sun+Earth, which certifies Green Bandit, and Dragonfly Earth Medicine have sprung up to offer clean weed credentials. California, the nation’s largest legal cannabis market, runs a “comparable-to-organic” certification program known as OCal.

Drawing from the organic and regenerative agriculture movements, green practices have proven successful for the Niestraths. Their products are distributed in hundreds of dispensaries across Oregon and have won multiple awards at the Oregon Leaf Bowl, a statewide competition sponsored by cannabis publisher Leaf Magazines. Their way of raising cannabis, however, remains a rarity in the broader market.

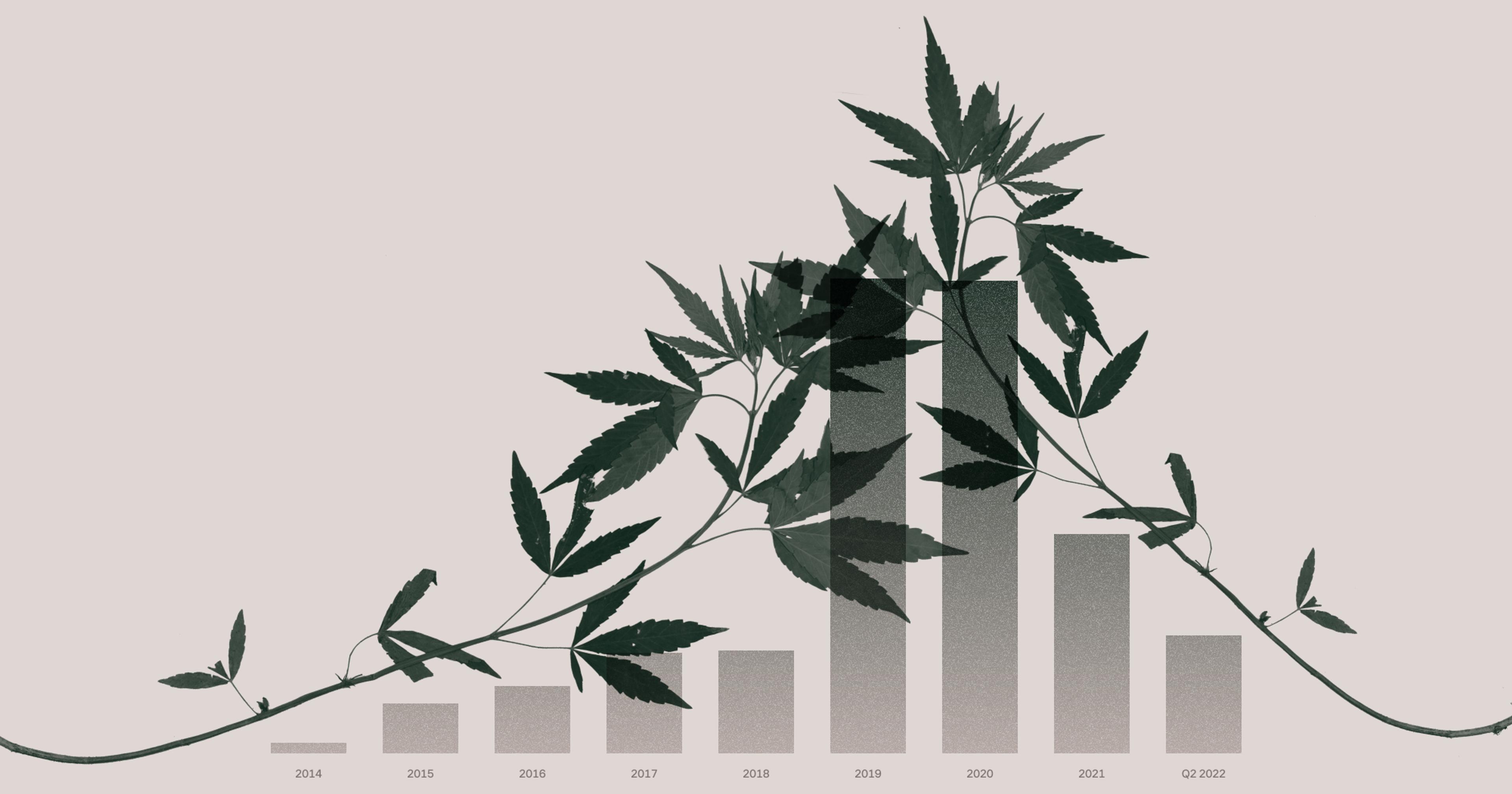

An ever-more consolidated cannabis industry has focused on growing in controlled environments with energy-intensive lighting, chemical pesticides, and questionable labor conditions. A 2021 Cannabis Business Times survey of commercial growers found that two-thirds grew exclusively indoors; just 11% farmed their weed entirely outdoors, as required by Sun+Earth and Dragonfly. (In recent years the USDA started allowing indoor-grown hydroponic produce to be sold as organic, a decision that’s drawn legal action from outdoor organic farmers and the nonprofit Center for Food Safety.)

Some growers hope that an increasing awareness of those issues, as well as the potential health concerns of industrially grown marijuana, will fuel consumer interest in doing things more naturally. They believe it’s possible to produce cannabis crops that are better for the planet, their customers, and their own bottom line.

Among the largest players in the clean weed market is California-based Coastal Sun. Darren Story, the brand’s CFO, says its $25-$30 million in annual sales make it the biggest of the 41 operations certified by OCal. (California officials said that they don’t separately track the sales of OCal-certified products; the state’s total cannabis sales reached $4.89 billion in 2023.)

“You have to get the right people who believe in what they’re doing and are willing to really get the shit kicked out of them by nature until they figure out how to do it right.”

Story says Coastal Sun’s approach is primarily driven by concerns over health — both of their customers and the plants themselves. He believes that the two are linked: Cannabis plants with more robust immune systems produce more terpenes, flavonoids, and cannabinoids, the chemical compounds that give weed its flavor and medicinal qualities. Similar boosts to antioxidants have been observed in organic produce, although it’s unclear if those differences lead to human health benefits.

When an organic system provides cannabis with the nutrients it needs, companion plants like sweet alyssum that attract pollinators, and beneficial insects like aphid-eating wasps, said Story, it also costs less to operate than a conventional farm with constant chemical inputs. But he admits that there’s a steep learning curve. Many companies, especially those funded by venture capital firms and seeking a shorter-term return on investment, don’t want to take the financial risks of the organic approach.

“You have to get the right people who believe in what they’re doing and are willing to really get the shit kicked out of them by nature until they figure out how to do it right,” he said, noting that Coastal Sun is self-funded. “We didn’t know any other way to do it; for us, it’s just growing plants.”

Despite the challenges, Story said Coastal Sun has kept up an average annual sales growth rate of about 28%, even as California’s overall cannabis sales have contracted more than 8 percent since their 2021 peak. Part of that success is due to strong demand from processors such as Jetty Extracts, which sells an OCal-certified line of vaporizers and infused pre-rolled joints.

Chief product officer Nate Ferguson said Jetty has also grown steadily against California’s broader headwinds. He cites an LA Times investigation from earlier this year, which found “alarming levels of pesticides” in dispensary products, as accelerating interest in the company’s clean weed approach.

Due to the premium Jetty pays for OCal-certified cannabis and its solventless extraction — a labor-intensive process that pulls medicinal compounds from the plant using ice water instead of chemicals like butane — its offerings can cost double what other brands charge for similar products. But Ferguson says that the upscale niche is more resilient to shifts in the market, with customers developing a strong brand loyalty.

“The message should really be, we have the best weed, and the reason is because we grow organically and regeneratively.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the clean weed industry, suggests Vin Deschamps, is getting consumers to try these products in the first place. He’s a board member for the Sun+Earth certification program and owner of the certified farm 54 Green Acres in Cave Junction, Oregon.

The legal weed market is still very young, Deschamps said, and entry-level customers tend to weigh their options based on the percentages of THC, the main psychoactive chemical in marijuana. Organically grown cannabis tends to have somewhat lower THC levels but much higher levels of terpenes and other compounds, which he said creates a much more enjoyable experience. (Judges at the California State Fair agreed, awarding six gold medals to Sun+Earth-certified farms this year.)

Deschamps is pushing for dispensaries to add “organic sections,” where budtenders can highlight clean products and educate consumers about their benefits. Eleven Oregon dispensaries have already signed on to the effort, along with several in California.

“Our message was almost apologetic, that you should buy us because we’re small farms and we care about the Earth,” said Deschamps. “The message should really be, we have the best weed, and the reason is because we grow organically and regeneratively.”

On a broader scale, Deschamps and other growers hope for looser federal regulations on marijuana that would allow them to ship across state lines. He compares the current situation to Napa Valley wineries only being allowed to sell in California — if connoisseurs across the country can’t buy the best, he argued, that limited customer base causes lower prices and discourages growers.

In the meantime, those looking for the cleanest, highest-quality weed may have to make a pilgrimage. “People around the world can buy my cannabis,” Deschamps said with a laugh. “They just have to come to Oregon to pick it up.”