Since the cannabis industry started to join the legal — and regulated — mainstream, workers who cultivate, process, and harvest the product are fighting for relief from low wages and dangerous working conditions.

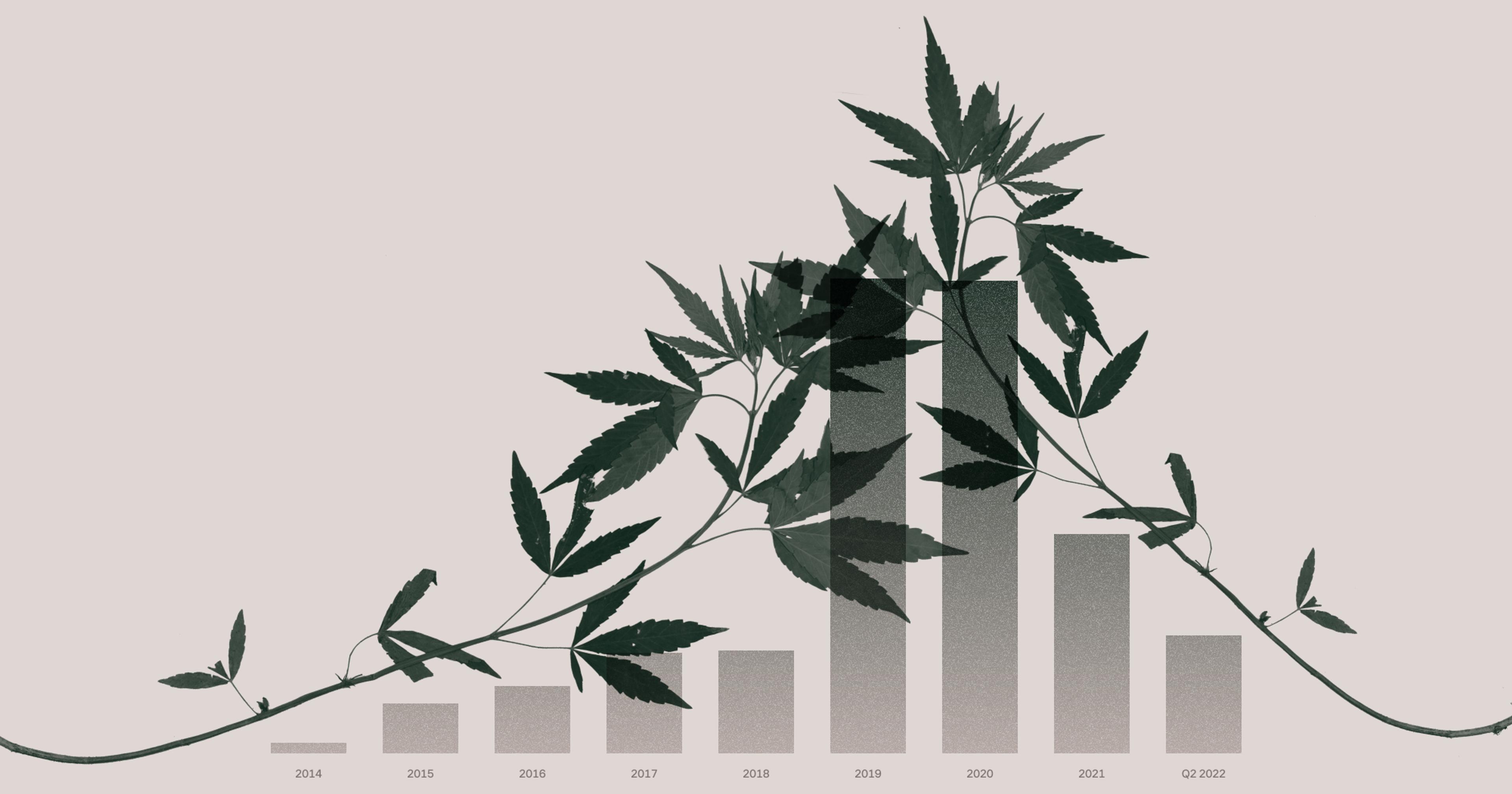

The U.S. market for cannabis is booming, with combined retail sales from medicinal and recreational marijuana expected to top $50 billion per year within the next three years. Sales from recreational marijuana alone, which is now legal in 24 states, surpassed $30 billion last year. The days of underground grow operations are rapidly fading; legalization continues to spread, subjecting cannabis to the same rules and oversight as all agricultural goods.

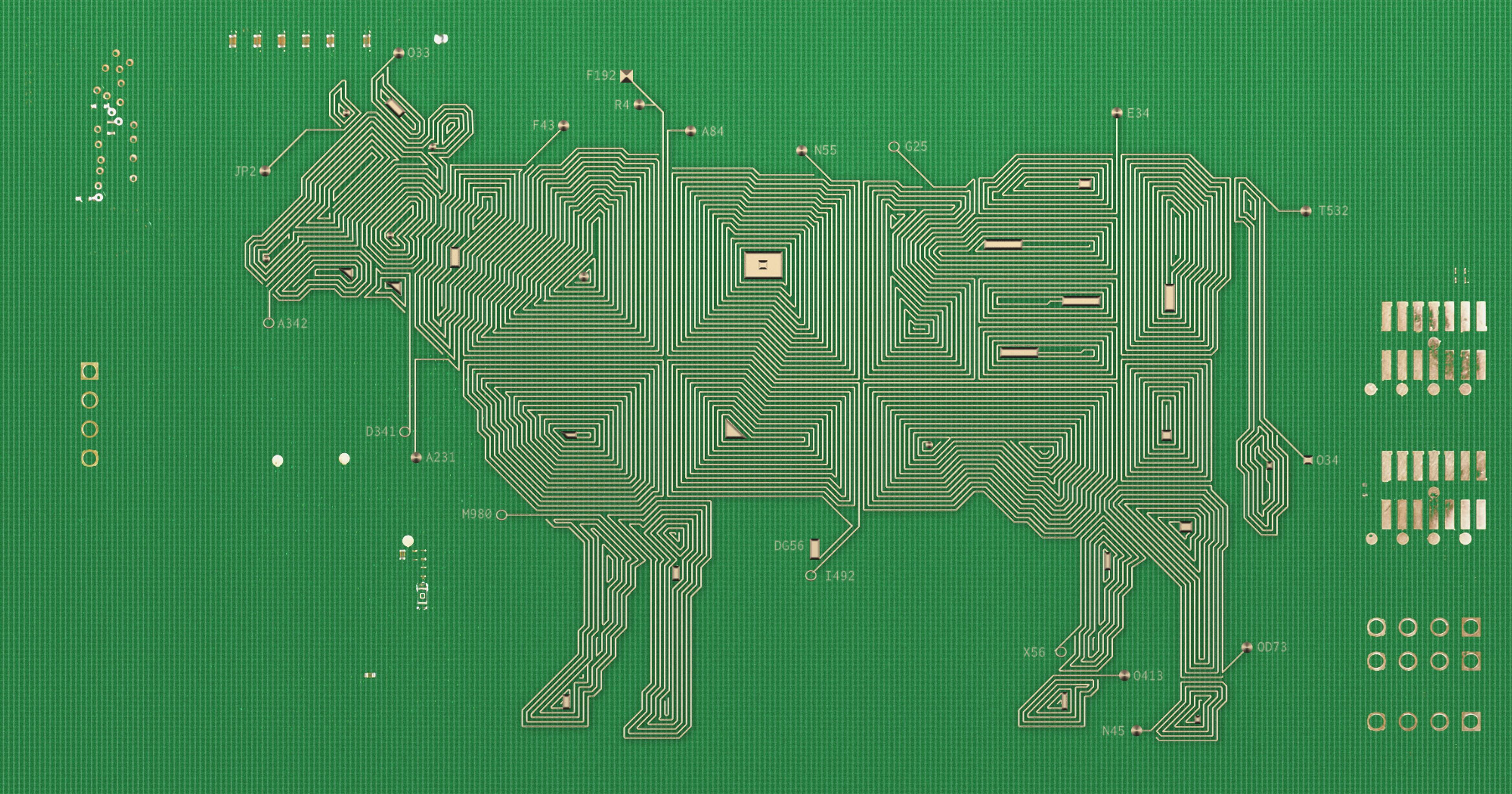

Cannabis work might seem like a cash cow in an industry with a slick and glossy reputation, but many of the workers who cultivate, harvest, and process cannabis have a different story to tell — one of grueling manual labor, hazardous working conditions, and low wages.

“Anytime I tell someone that I work in the cannabis industry, they tend to say, ‘Wow, that must be a chill job,’” said one post-harvest technician at Sinse Cannabis in Missouri, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation. But, they continued, “It’s not. In fact, it’s the most stressful job I’ve ever had.”

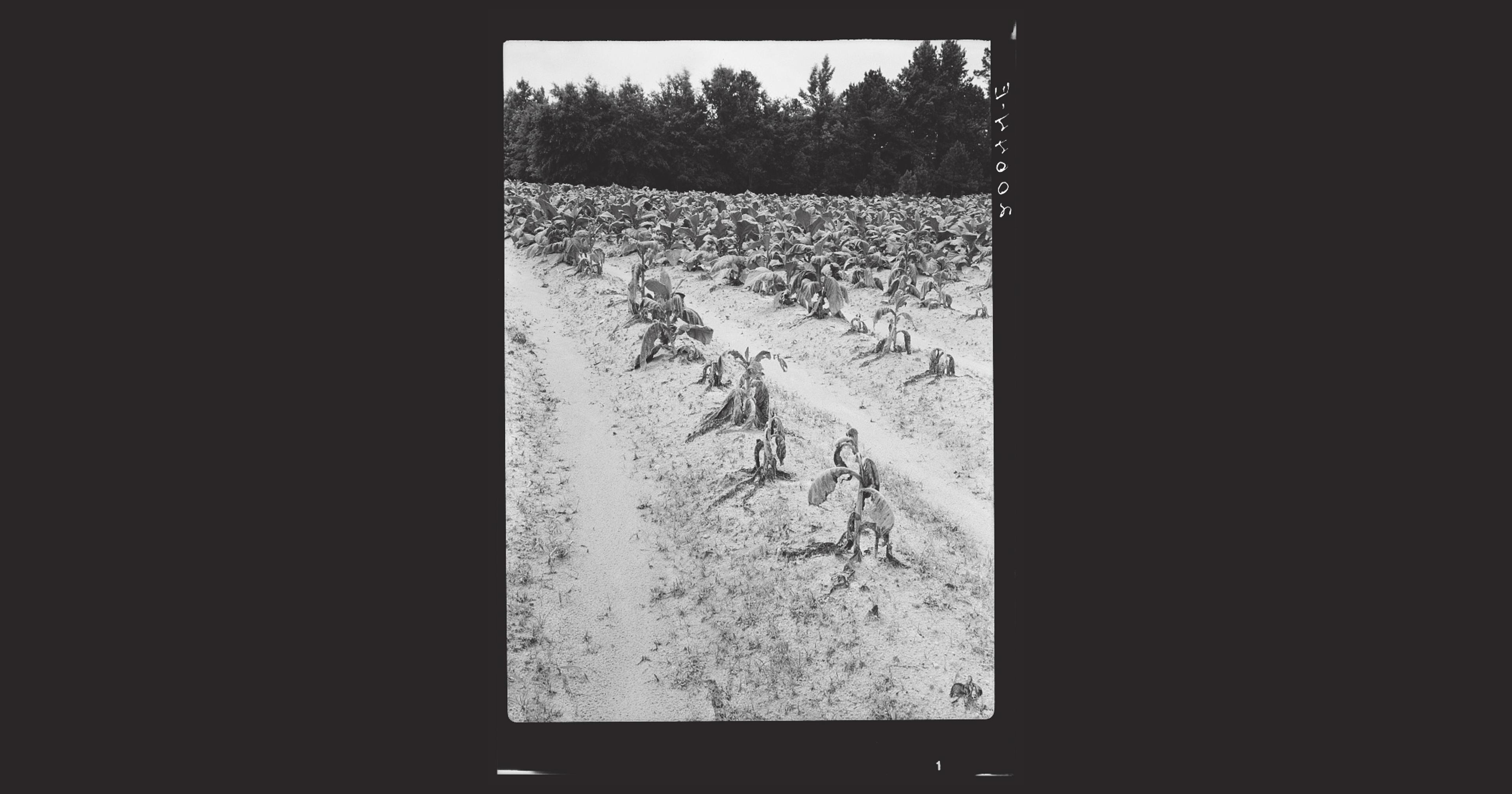

Some of the struggles facing those in cannabis cultivation and processing will be familiar to workers in other agricultural industries, while others are unique holdovers from an era when cannabis was the domain of back alley deals and questionable additives.

Cannabis cultivation often involves working with pesticides and other chemicals, operating heavy machinery, and performing taxing manual labor. Anthony Sykes, a harvest technician at Green Dragon in Denver, Colorado, said he and a team of nine other workers often harvest and break down as many as 2,500 plants in a week. This involves cutting the several-foot-tall plants at their base using shears, then breaking off and stripping their branches. After harvesting, the team cleans up debris and wipes down or power-washes walls and surfaces. Sykes drives a Zamboni to polish the floor.

Working in extreme heat is one of the most challenging parts of agriculture work in general — and cannabis work in particular. Most cannabis is cultivated in industrial greenhouses, and heat and humidity are intensified year-round thanks to the use of grow lamps. “The thermometer could be telling us it’s 91 degrees in there with 75 percent humidity or 80 percent humidity, and it feels like 110,” said Sykes.

Cannabis processing workers who turn raw hemp and cannabis plant biomass into products for sale through a range of processes, from pre-rolling joints to producing cannabis concentrates in a lab, can also face heat stress and exposure to chemical and biological hazards. Jimena Peterson, organizing director at United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) Local 7, which represents workers in Colorado, said she has seen cannabis workers develop rashes and respiratory problems on the job. “Safety for them is something that is very concerning,” she said.

“Anytime I tell someone that I work in the cannabis industry, they tend to say, ‘Wow, that must be a chill job.’”

While cannabis remains an illegal substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act, federal courts and regulating bodies have nonetheless taken note of wage and safety issues and demonstrated some willingness to enforce standards in the industry. Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labeled occupational allergic diseases like asthma among post-harvest workers “an emerging concern.” The death of 27-year-old Lorna McMurrey, a production worker who had a fatal heart attack at her workstation in January 2022 after cannabis dust exposure caused her to develop asthma, garnered scrutiny nationwide. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has also fined cannabis businesses in multiple states — including Trulieve Cannabis in Massachusetts, which employed McMurrey at the time of her death — for failing to protect employees from workplace hazards.

For all the dangers they face, most cannabis workers earn between $14 and $22.50 per hour, or about half of the average hourly wage for all workers in the U.S. “Most of us have second jobs or a side hustle just so we don’t drown,” said the post-harvest technician at Sinse Cannabis.

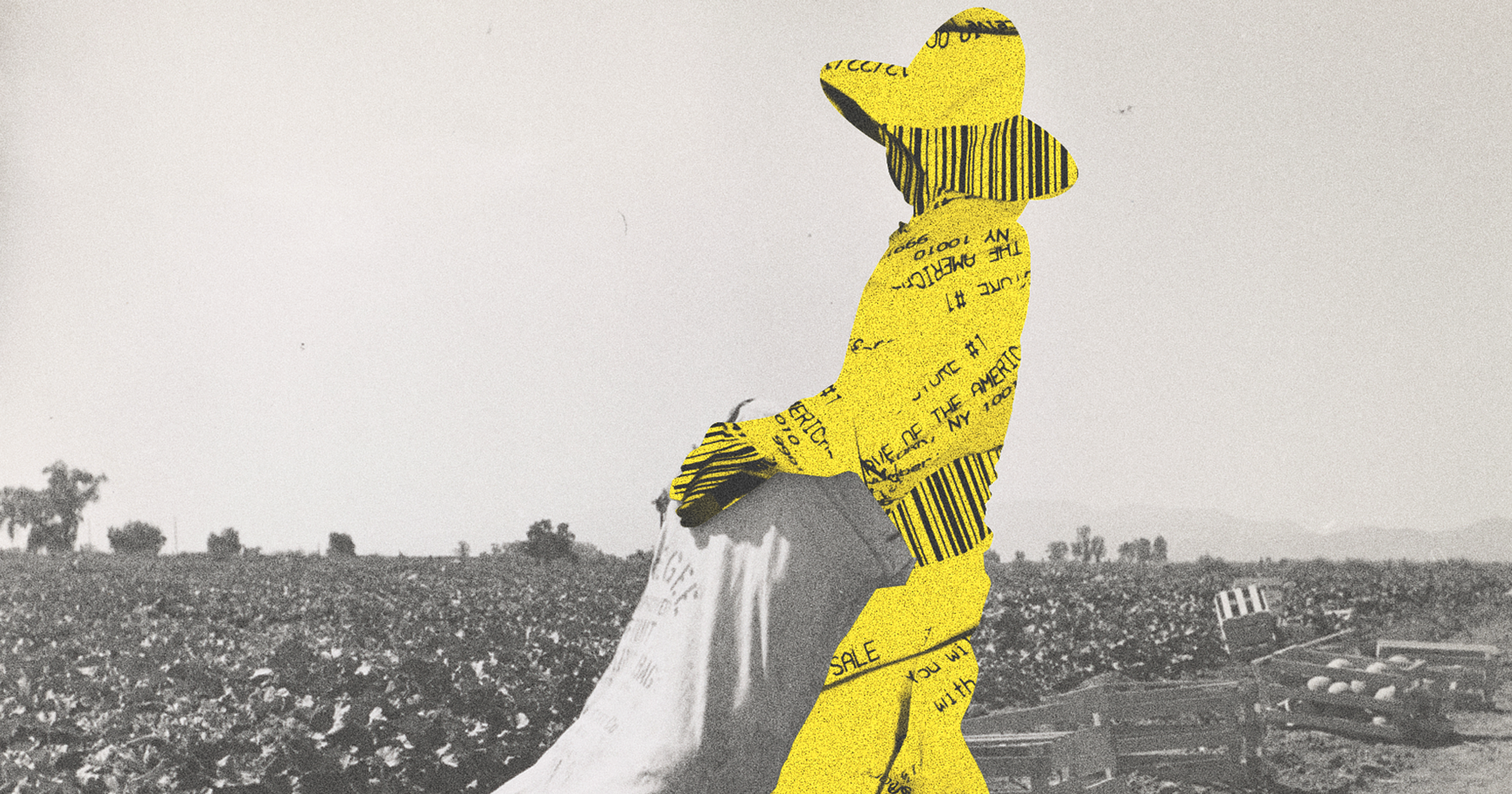

Many cannabis workers are also on part-time or temporary contracts, excluding them from employer-sponsored health insurance programs. Some, categorized as agricultural workers, are also exempt from minimum wage, overtime, and other wage and hour rules under state or federal law. While there is no comprehensive data available on the demographics of the cannabis labor force, research suggests it mirrors other agricultural industries, comprising an outsized portion of migrant laborers who are even more vulnerable to wage theft and other abuse.

Seeking relief from these conditions, cannabis workers have begun organizing nationally. The anonymous post-harvest technician at Sinse Cannabis is one of them, and the union drive at that facility could have major implications for national labor law.

Since last September, when employees in the processing, lab, and order fulfillment departments at Sinse filed a petition to unionize, parent company BeLeaf Medical has become the sticking point in a case before the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). BeLeaf argues that the post-harvest workers at its Sinse Cannabis facilities are agricultural workers and, therefore, not protected or allowed to unionize under the 1935 National Labor Relations Act. Because this is the first time the national board has been asked to consider the issue, its eventual decision will set a national legal precedent.

For those who may have been in the cannabis trade before it was legalized and are now transitioning into running a legal business, old habits die hard.

While the national board has yet to weigh in, Andrea Wilkes, NLRB regional director for Missouri and five other states in the Midwest, already ruled against BeLeaf Medical’s argument twice this year. Her decisions aligned with another regional ruling from September 2023 regarding a group of post-harvest workers in New Jersey. However, those decisions have not stopped BeLeaf from asking the federal government to intervene in its case. Nor have they stopped the company from allegedly punishing workers who backed the union push.

Elsewhere in the industry, labor wins offer hope. At Green Dragon, a successful campaign to unionize with UFCW 7 allowed employees to secure better wages, vacation time, and personal protective equipment. Colorado has state legislation enabling agricultural workers to unionize, so Green Dragon management could not contest the election like BeLeaf Medical has in Missouri. Still, workers faced retaliation for their efforts.

Matthew Shechter, legal counsel at UFCW 7, attributes some cases of union-busting and other suspect business practices to “the nature of the cannabis industry, where you’ve got a lot of fly-by-night type of operators.” For those who may have been in the cannabis trade before it was legalized and are now transitioning into running a legal business, old habits die hard.

“There have been other campaigns where we have started having conversations, and we find out that the employers are paying their workers in cash, or they’re not paying them correctly,” said Peterson, who has worked on campaigns to organize cannabis workers at grow facilities and dispensaries across Colorado. Similarly, issues in Michigan, California, and New Mexico have led to class action lawsuits filed against cannabis companies on behalf of hundreds of workers, alleging minimum wage and overtime violations.

Peterson said some companies even take drastic action to avoid bargaining with workers: “When they hear that their employees are trying to unionize, all of a sudden, they’re like, ‘Oh, we’re going to close the grow house.’”

“We want to watch this industry that’s making billions of dollars benefit the people that are actually working it.”

Top-down decisions like that can be heartbreaking for workers, not only because they lose income but also because many do not want to leave behind an industry they love and are excited to work in. Finding new jobs can be difficult, especially in states like Missouri and Arizona, which issue only a limited number of identification cards that allow individuals to work in cannabis. Peterson said workers also fear being de facto blacklisted if owners at one operation label them troublesome and warn others.

While damning patterns of employer behavior have emerged in some sectors of cannabis, there are also examples of more responsible paths forward. One way to foster better relations between employers and workers is labor peace agreements, which establish a period during which a union agrees not to disrupt an employer’s business operations in exchange for the employer agreeing not to undermine union organizing.

Proponents, including UFCW, argue that labor peace agreements facilitate collective bargaining and promote fair labor practices, leading to better conditions for cannabis workers. Some states, including California and New York, require cannabis businesses to sign such agreements with certified labor organizations to obtain licenses. (Though California had some issues with companies inking agreements with fake unions.) This November, a ballot measure in Oregon could see that state added to the list.

Sean Shannon, lead organizer with UFCW 655, the union local Sinse Cannabis workers are fighting to join, said the answer is not less engagement with unions but more. “The workers want to take care of this business,” Shannon said. “They want to help, and we want to watch this industry that’s making billions of dollars benefit the people that are actually working it.”

BeLeaf Medical and Green Dragon did not immediately respond to requests for comment; we will update this story with any responses.