Corn detasseling continues to be a beloved Midwestern tradition, as youth labor regulations progress and migrant workers compete with the young workforce.

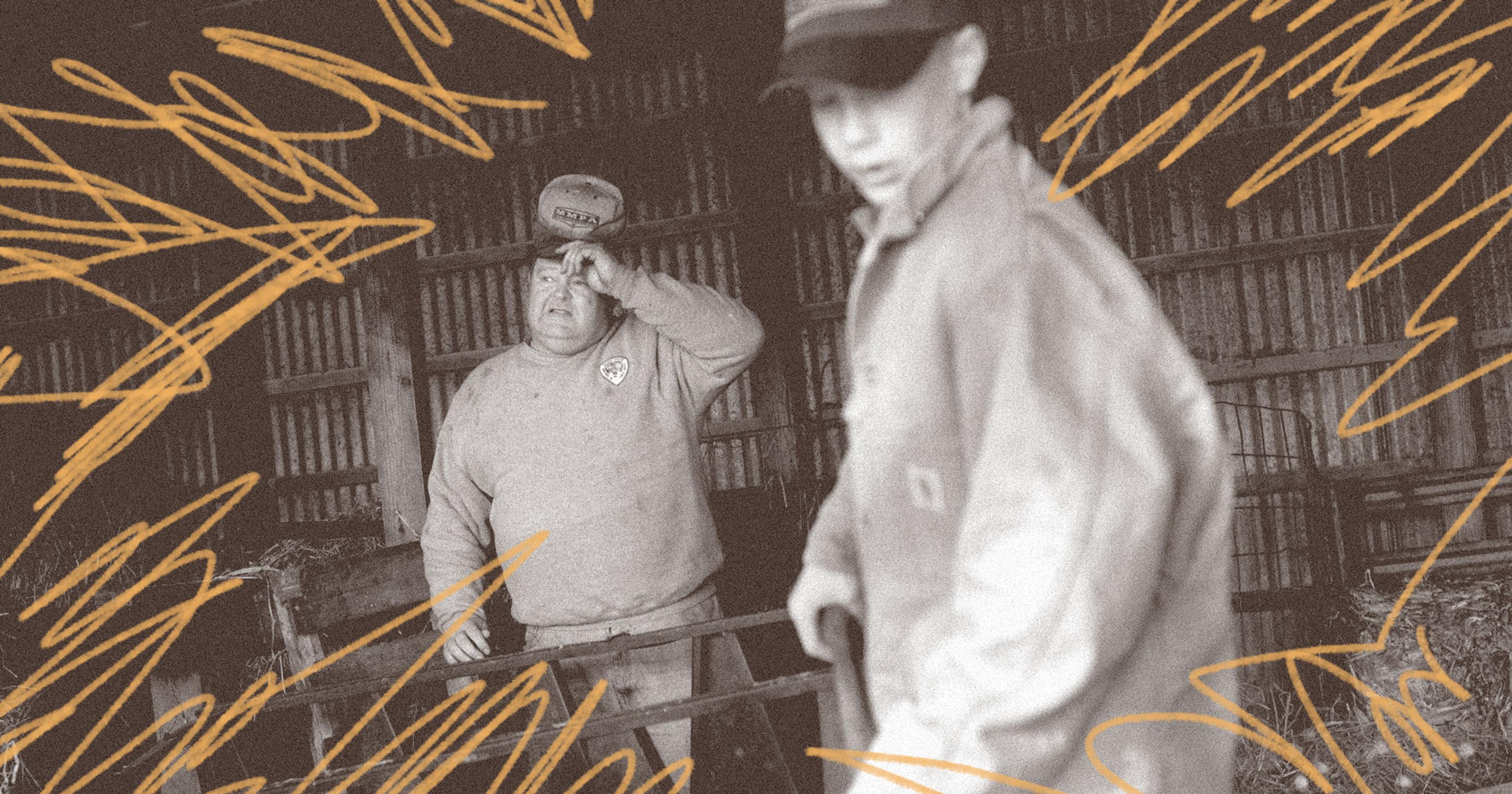

Each summer, thousands of teenagers across the Midwest step into rows of seed corn fields before sunrise. In an age-old tradition, these teens have ridden buses from small towns and city centers to lace up their tennis shoes, fan out across the field, and perform one of agriculture’s youth-labeled jobs: corn detasseling.

Detasseling is a step in seed corn production that involves manually removing the male tassel from the female corn plant to prevent self-pollination. It’s a vital part of a massive Midwestern industry, usually happening during July. In Nebraska, Matt Schulte grew up in Grand Island detasseling corn in the late 1990s. He was a part of a seasonal workforce that still stretches across the Corn Belt today, working just one month a year.

Schulte learned hard work and the realities of farm life, plus what residents call the “Midwestern Spirit.” Now a father, pastor, and county commissioner, he passed that experience down to his own three kids. “The place where I drop off my kids each morning … there are six buses that pick up kids just at one site.” Just as students everywhere load buses for sports, Nebraska kids climb aboard the same buses in summer, bound for the cornfields. One company alone picks up teen workers at five different locations around Omaha, Schulte said.

More than 7,000 people detassel each year in Nebraska, according to the state; 80 percent of them are under 18. Row crop production pairs well with the availability of rural farm kids, who have long performed chores before they ever clock hours onto a timesheet. In an era of labor shortages, mechanization, and shifting youth priorities, these teen workers serve as a rare, essential link in the farm labor chain.

The national shortage of skilled workers has always left the door open for entry-level job seekers. Roughly 70 percent of agriculture businesses report needing to hire and train inexperienced employees, according to the Midwest Food, Agriculture and Forestry Workforce Needs Assessment. Enter youth labor in agriculture. An estimated 600,000 workers are in agriculture under the age of 18, according to the most recent Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey.

With parental consent, children as young as 12 can work in non-hazardous farm jobs, typically outside of school hours. At 14, teens may work in a wider range of non-hazardous farm roles. At 16, they may perform hazardous agricultural work without restrictions on hours. At 18, they can work in dangerous jobs across both agricultural and non-agricultural industries.

Federal regulations under the Fair Labor Standards Act set the national minimum for child labor protections, but agricultural exemptions allow states to loosen youth employment rules — with exact regulations varying from state to state.

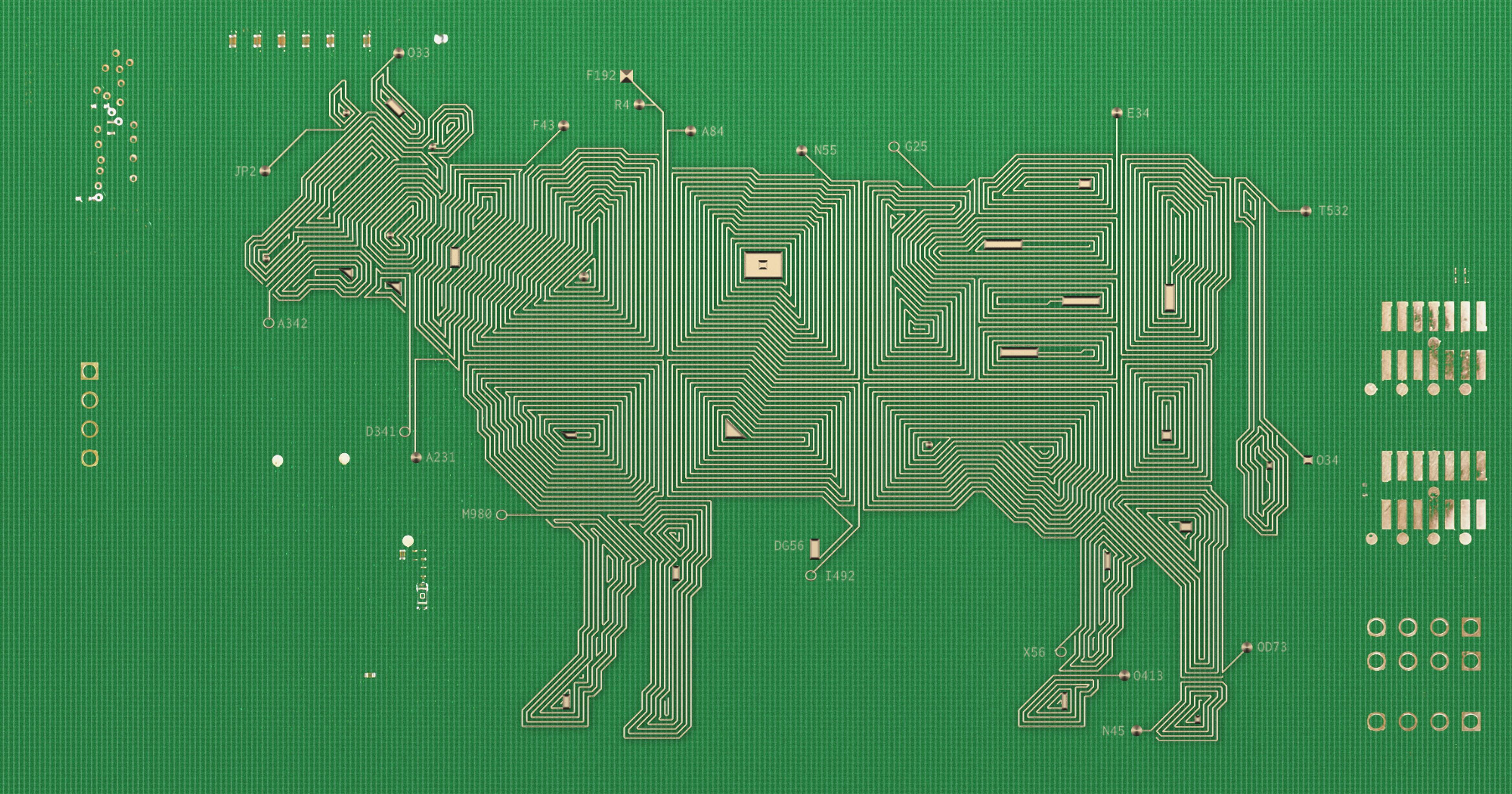

Around the country, children are picking strawberries, baling hay, cleaning pens, and feeding livestock. But in row crop country, detasseling is king. The detasseling process is controlled, allowing for cross-pollination between selected parent plants, enabling the production of hybrid seed. Machines remove about 75 percent of the male tassels, but workers must walk miles of rows to identify and pull the rest by hand. Timing is critical because removing them too early and your yield suffers; too late, and the corn pollinates itself.

Nick Grandstaff is an Iowa native who detasseled for DuPont Pioneer in his younger years. Come the end of June, “Everyone in town either opted into detasseling or found another job,” he said. Reflecting on why the market exists, Grandstaff pointed to regions like North Central Iowa, where fertile soil and nearby seed processing plants create the right business conditions. In those towns, all youth, regardless of background, took part.

“Mechanization can only go so far in detasseling,” he said. “Well-motivated youth get the job done.”

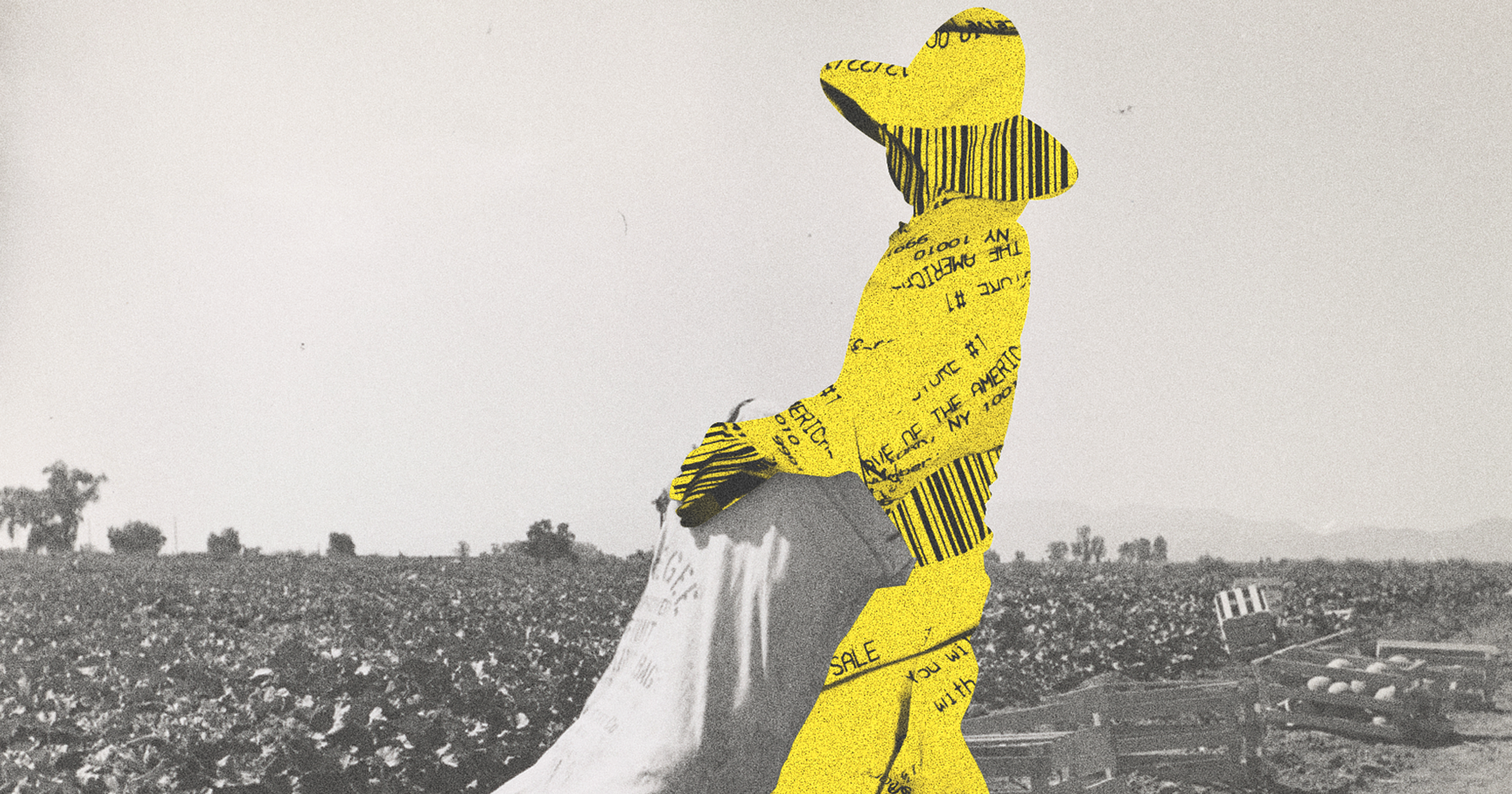

For many teens, detasseling is a summer side job — a way to earn spending money. But in the broader under‑16 farm workforce around the country, many have low-income family responsibilities that extend beyond pocket money. According to the Lawyers for Good Government, over 90 percent of children agricultural workers are persons of color. Within that percentage, 83 are identified as Hispanic.

The USDA reports that up to 7% of crop production workers are aged 14 to 19. The size of this child labor population complicates assumptions that teen wages rarely contribute to household needs, undercutting opponents of minimum wage spikes. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that nearly 45 percent of minimum-wage jobs are held by workers ages 16 to 24.

“The original idea behind farm exemptions in youth labor law was to help family farms survive.”

As demand for cheaper labor grows, the detasseling capital of America is outsourcing to migrant crews that follow harvests from south to north, replacing thousands of teen jobs with lower-paid adults whose wages must still meet the federal minimum.

Nebraska county commissioner Schulte took issue with that when he published an op-ed protesting reduced detasseling access for local teens. “Large seed producers have found that they can improve their bottom line by outsourcing detasseling and rogueing to migrant worker companies,” he said.

Companies like Bayer, Syngenta, and Remington Seeds all utilized the H-2A visa program to fill these labor crews. Adults over the age of 18 years old qualify for H-2A visas, but their children or dependents are not authorized to work themselves, under the H-4 visa — a rule often broken.

Starting in 2019, the United States Department of Labor and state of Nebraska feuded when the state argued its teens were ready to detassel corn, while the federal agency continued approving H-2A visas for migrant crews.

The model is not new — migrant crews have long filled agricultural labor gaps — but outsourcing a job historically held by local teens has sparked concern. In 2024, Nebraska lawmakers passed LB844, a bill requiring seed companies to make documented efforts, submitted to the state, to recruit local youth before hiring out-of-state migrant crews. The law adds steps beyond the H-2A program’s basic recruitment strategies like newspaper posting.

Defending teen access to tough farm jobs is neither politically easy nor popular. But advocates argue the bill does more than protect jobs — it preserves young people’s exposure to agriculture. “We need to protect migrant workers from these unhealthy, harsh conditions,” Schulte said about the traveling team who work all year-round. “We need to protect Nebraska jobs,” he also said, revealing a complicated dichotomy: Should the unhealthy, harsh conditions be reserved for native-born youth?

Schulte says his eldest son earned $12,000 over his years detasseling, enough to buy a pickup truck outright. “Every dollar he used to pay for that thing came from those fields,” he said. “Once he realized how much he could make, he was all in.”

The broader farm workforce is also “all in”— but only if they’re allowed to stay in the country to work. In July 2025, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins doubled down on a zero-amnesty policy for foreign labor, calling for a fully American farm workforce. She pointed to Medicaid recipients as potential replacements for the millions of farmworkers her administration has sought to deport; differing state laws could expand the role of teen workers even further.

Youth labor protections in agriculture were created to shield minors from hazardous work, prevent exploitation, and ensure children stay in school. Even for the youngest workers, the law sets age minimums, mandates breaks in some states, and limits tasks based on risk, said Jeffrey Lewis, an attorney with Ohio State University’s Agricultural & Resource Law Program.

But enforcement and legal standards vary widely by state and often depend on how each job is classified. And right now, various states are both strengthening and loosening their child labor protections.

“Mechanization can only go so far in detasseling. Well-motivated youth get the job done.”

In Iowa, lawmakers recently introduced legislation that would allow 14-year-olds to work in meatpacking plants under certain conditions. In Ohio on the other hand, a new rule bars youth under 18 from handling restricted-use pesticides, a change expected to directly affect small grain and row crop farms.

This patchwork of regulation has created inconsistencies in how, and whether, youth can participate in farm work legally. “Youth employment is particularly nuanced in employment law,” Lewis said. “The distinction matters.” Field labor, meatpacking, and equipment use each fall under different legal categories and are not governed by a single standard when state law superseded federal law.

Some critics note that detasseling is often done in peak July heat for eight hours a day, and is too demanding for minors. Their concerns are backed by a 2018 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, which found that more than half of all work-related youth fatalities occurred in agriculture.

The Fair Labor Standards Act sets a national baseline, but states can impose stricter rules — or attempt to loosen them. Fieldwork like corn detasseling qualifies as “agricultural labor,” which is broadly exempt from many child labor restrictions. By contrast, meatpacking, though often discussed in the same context, is not considered agricultural labor under federal law. Instead, it is classified as manufacturing and processing, industries deemed too hazardous for workers under 18.

Illegal child labor in meat processing remains common. In 2025, JBS USA settled for $4 million dollars with the Department of Labor. In 2024, 11 children, some as young as 13, were found working at Seaboard Triumph in Iowa. Regardless, many states have further legislated to operate with a younger workforce; Iowa, for example, allows work permits for children as young as 14 to work in meat coolers and industrial laundries, restricted workplaces under federal law.

“The original idea behind farm exemptions in youth labor law was to help family farms survive,” Lewis explained. But today, those exemptions now apply on a much broader scale across the economy. One of the big conversations now is whether we are doing enough to protect young workers, he said.

Depending on who you ask, you might get very different answers.