New research from the Texas Department of Agriculture makes a case that state policies have largely not acknowledged — climate issues are a threat to agriculture and the local food supply.

For Becky Tamez, CEO and co-founder of Isle Acre Farms in Leander, Texas, her land is everything. It explains why Tamez, whose operation primarily grows eggplant, cherry tomatoes, and carrots, has proactively set up her operation to endure extreme weather — and, more specifically, extreme temperatures.

“In the last few years, we’ve seen significant freezes even into negative numbers, in which vegetables cannot survive,” she said “At this point moving forward, we’re going to try to implement a more significant grow season during the spring, summer, and fall and try not to even attempt farming during the winter.”

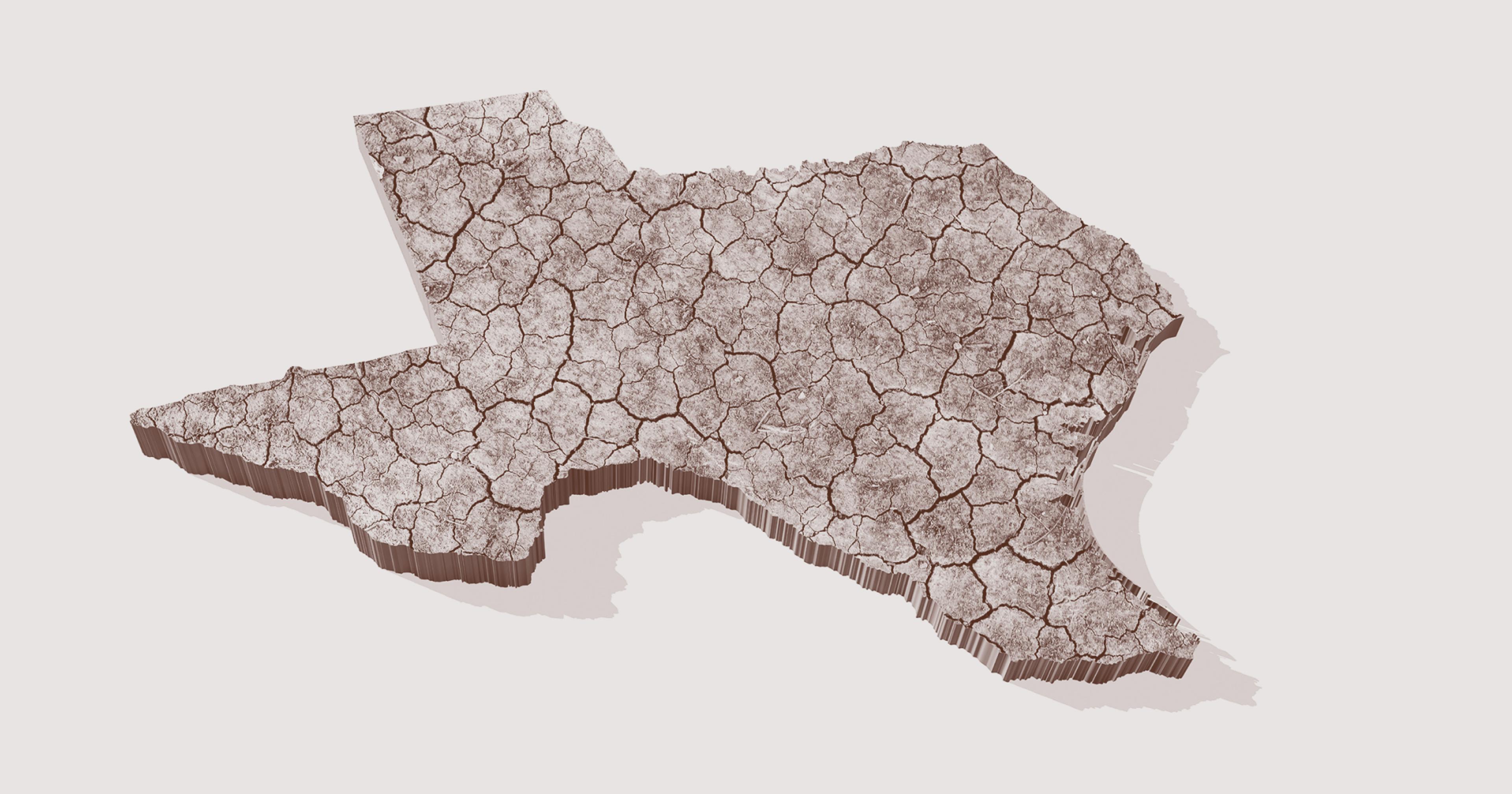

Texas, America’s most-populous Republican state, has long pushed back against climate mitigation initiatives, even as localized climate and weather events increase in severity. Yet following recent record-breaking drought conditions and extreme cold spells, the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA) released a food access study linking climate change to its potentially crippling effects on the state’s food supply.

The study, coordinated by TDA and the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, interviewed a host of professionals working in the food system across Texas to evaluate the state’s most pressing needs. This included members of the grocery industry, state and federal government employees who work on food-related programs, academics, advocates, and agriculture specialists. The goal was to assess various factors leading to food insecurity in the state — climate issues were front and center throughout the study.

For instance, the report noted that “‘climate instability’ is strongly associated with soil loss, water quality, droughts, fires, floods, and other environmental disasters,” all of which affect the state’s food supply.

In total, Texas received similar amounts of rainfall in 2022 as 2021, but the majority of it came all at once during the end of the summer. The average daily temperature in the state has slightly increased over the last four years, and 2022 was one of the driest years on record for Texas, with roughly 49 percent of the state still in drought conditions at the end of December.

“As long as climate change continues, the tendency for worse agricultural drought conditions will continue,” said John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas State Climatologist and regents professor at Texas A&M University. “[T]here will still be good and bad years and decades, but the bad years will tend to get worse over the long haul.“

Nielsen-Gammon added that natural variability makes it hard to be a crop producer in Texas, as there are large swings between wet and dry years.

“It would be easier if farmers could just assume that all trends are temporary, but that’s no longer the case.”

“It would be easier if [farmers] could just assume that all trends are temporary, but that’s no longer the case,” he said. “Climate change may require a permanent switch to crops that are more heat-tolerant and drought-tolerant, with lower but more reliable yields, or crops that grow notably better under higher carbon dioxide conditions.”

Released this past December, the report listed supply chain stability and climate-related stability as primary concerns, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The study also noted that climate-related migrants have increased, similar to displaced residents from Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey. Concerns were expressed regarding droughts, drying up of artisanal wells, water use restrictions, fire threats, and dangerous conditions for farmworkers, all of which led back to food supply concerns.

In response to these challenges, the report recommends farmers work alongside researchers and policymakers, improving water quality and building stronger communication networks in local agriculture.

“Agricultural producers rely on intimate knowledge of their own land and how it responds to variations in the weather,” said Nielsen-Gammon. “If the weather becomes different, with hotter and more rapidly developing droughts, that valuable experience becomes a little less valuable.”

Nielsen-Gammon declined to discuss Texas’ overall resistance to green policy initiatives, and how that may impact the state’s agriculture and food supply moving forward. But politicization is to be expected.

Consistent resistance from Texan lawmakers has made it challenging for climate-forward legislation to pass.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott blamed green energy during the historic winter storm of 2021 that left millions of Texans without power, but the state runs on fossil fuels. He signed an executive order in 2021 that would “direct every state agency to use all lawful powers and tools to challenge any federal action that threatens the” energy sector in Texas. And in December of 2022 Republican lawmakers interrogated investment companies for shifting to climate-friendly portfolios, arguing that these companies are not following Senate Bill 13, which prohibits the state from contracting with or investing in companies that divest from oil, natural gas, and coal companies.

The consistent resistance from Texan lawmakers has made it challenging for climate-forward legislation to be passed. But for those looking for more immediate change, the stakes of climate change mitigation are more important than ever.

“Another source of tension is the state and local governance willingness to work closely with industry rather than community-driven organizations,” said climate activist Joey Gonzales, a native of Corpus Christi, Texas.

Gonzales most recently held the title of community organizer for Chispa Texas, an organization that advocates for healthier environments in Latinx communities. Chispa is one of many groups on the ground, fighting for structural change.

But it’s not just progressive advocacy organizations who recognize the stakes are high for Texas. The Texas Farm Bureau, a large legacy organization for farmers and ranchers in the state, lists sustainability and climate-related issues as a top policy priority. While acknowledging some practices might be costly or challenging to adopt, the organization encourages farmers to reduce their carbon footprint through management practices that sequester carbon dioxide, utilize no till-farming, and implement the planting of cover crops.

“At some point in the near future, the agricultural industry will not be able to keep up with increasingly erratic and severe climate fluctuations.”

“Agriculture is eager to be part of the solution,” said Texas Farm Bureau President Russell Boening. “As farmers, we play a leading role in promoting soil health, enhancing wildlife habitat, and conserving water and natural resources as we grow our crops and raise livestock.”

The Texas Farmers Union (TFU) is even more outspoken on these issues, strongly arguing that climate change poses an existential threat to the state’s agriculture industry and food supply. “Farmers have, for the most part, been able to compensate for previous climate shifts with a combination of technology and innovative management,” reads their most recent policy document. “But at some point in the near future, the agricultural industry will likely not be able to keep up with increasingly erratic and severe climate fluctuations.”

Attitudes about climate change are slowly shifting, and more mitigation efforts might be on the horizon as more Texans acknowledge the realities. Almost 81 percent of Texans say they believe climate change is happening, according to new research by UH Energy and the University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs. Slightly lower percentages said they believe the change is driven by human activities.

For their part, Gonzales believes in Texans’ ability to create “alternative futures and realities, where we don’t have frequent water boils, where we can breathe easier, and where we don’t have oil spills in our bay,” said Gonzales. “With the current change of culture, I have hope for these futures and realities.”