A new study from North Carolina State University surveyed people throughout the phosphorus industry, finding dim views on its long-term sustainability.

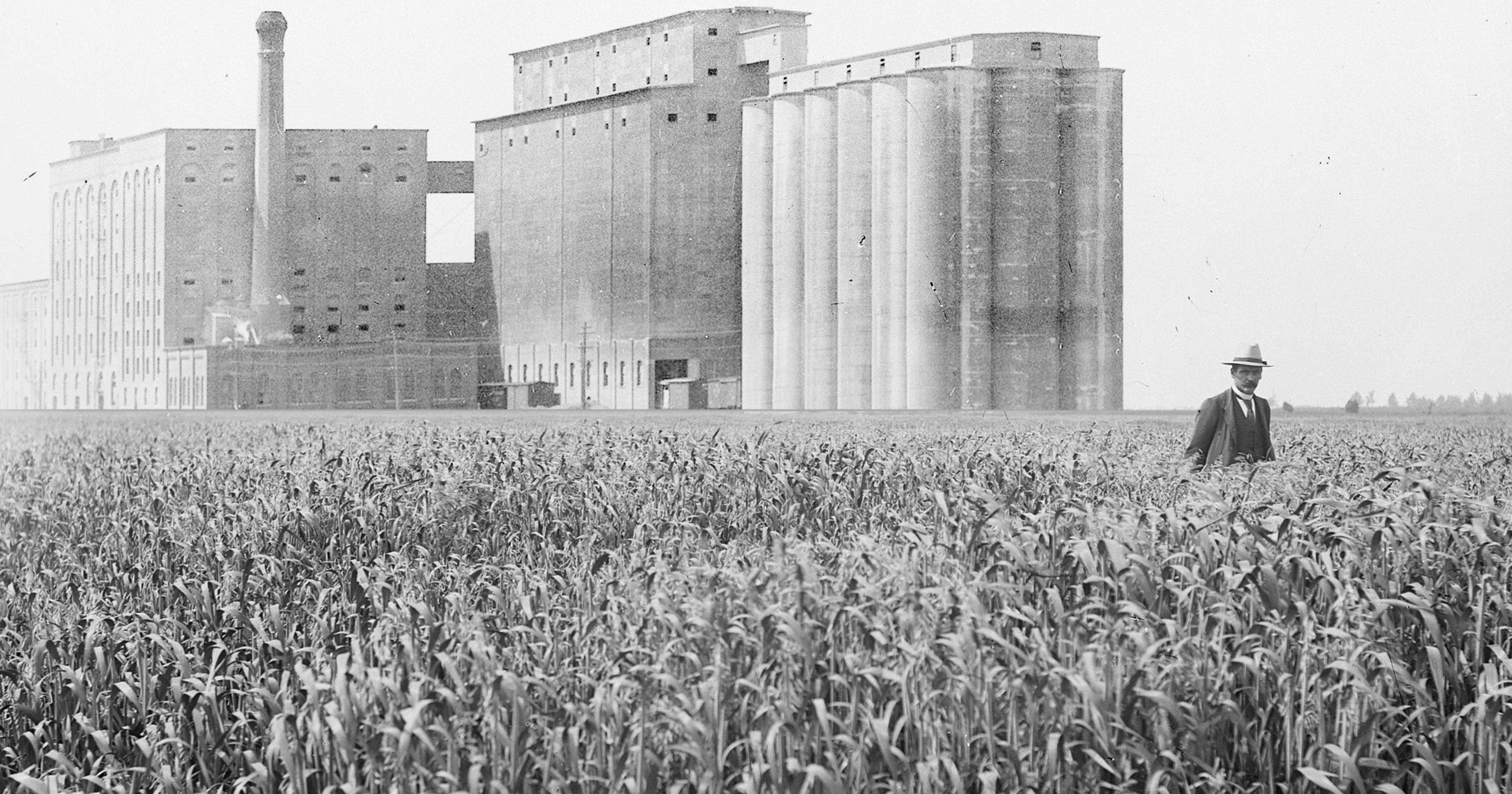

Phosphorus, an element present in all living things, is an essential nutrient for growing crops; conventional farmers have relied on it as a main ingredient in the fertilizers that fuel their soil for many decades. But rock phosphate, the raw material that is mined and transformed into fertilizers, is a non-renewable resource in high demand — and supply is not abundant.

On the path toward more sustainable use of the finite phosphorus supply, a new study by North Carolina State University polled a swath of phosphorus stakeholders — think farmers, fertilizer executives, environmentalists, and policymakers — to gather their thoughts on how sustainable, or not, the current system for managing the resource is, and what could stand to change.

As it turns out, they are concerned.

More specifically, the results of the study showed that the majority of participants had significant doubts about the long-term sustainability of existing phosphorus management systems. Participants were concerned about the existing challenges of capturing and reusing phosphorus — much of it washes out of fields and into waterways — and the fact that phosphorus is a finite resource. The scarcity of the substance will only continue to grow.

Slightly over 30% of study respondents found the current “mining, use, transport, recovery, recycling or disposal of phosphorus and materials containing phosphorus” completely unsustainable. One step below unsustainable, as the language of the survey put it, was “slightly sustainable,” and another 45% of participants said current practices fell within that category.

One respondent — all participant feedback was anonymous to the researchers — summed up their concerns and said, “Relying on a mined, non-renewable resource for an essential nutrient for all life, while the excess is lost to landfills and water bodies is just not sustainable.”

For farmers, especially those who grow heavily phosphorus-reliant commodity crops like corn and soy, this leaves them with a market in which it’s been increasingly difficult (and costly) to get their hands on phosphorus fertilizers.

According to a global assessment by Our Phosphorus Future, a project that came from a partnership between the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the University of Edinburgh, “1 in 7 farmers cannot afford sufficient fertilizers to maintain fertile soils, impacting their ability to produce food.”

Khara Grieger, an assistant professor of environmental health and risk assessment at North Carolina State University, co-authored the new research. The team sent out a 14-question survey, with the idea that to develop systems and policies that lead to long-term phosphorus sustainability, first there needs to be an understanding of everyone’s needs, wants, and concerns.

“Our current systems for managing a finite resource of phosphorus are no longer sustainable.”

“The reason why we’re investigating this is because of something we’ve known now for quite a while, I would say at least a decade or 15 years; that our current systems for managing a finite resource of phosphorus are not no longer sustainable.” said Grieger.

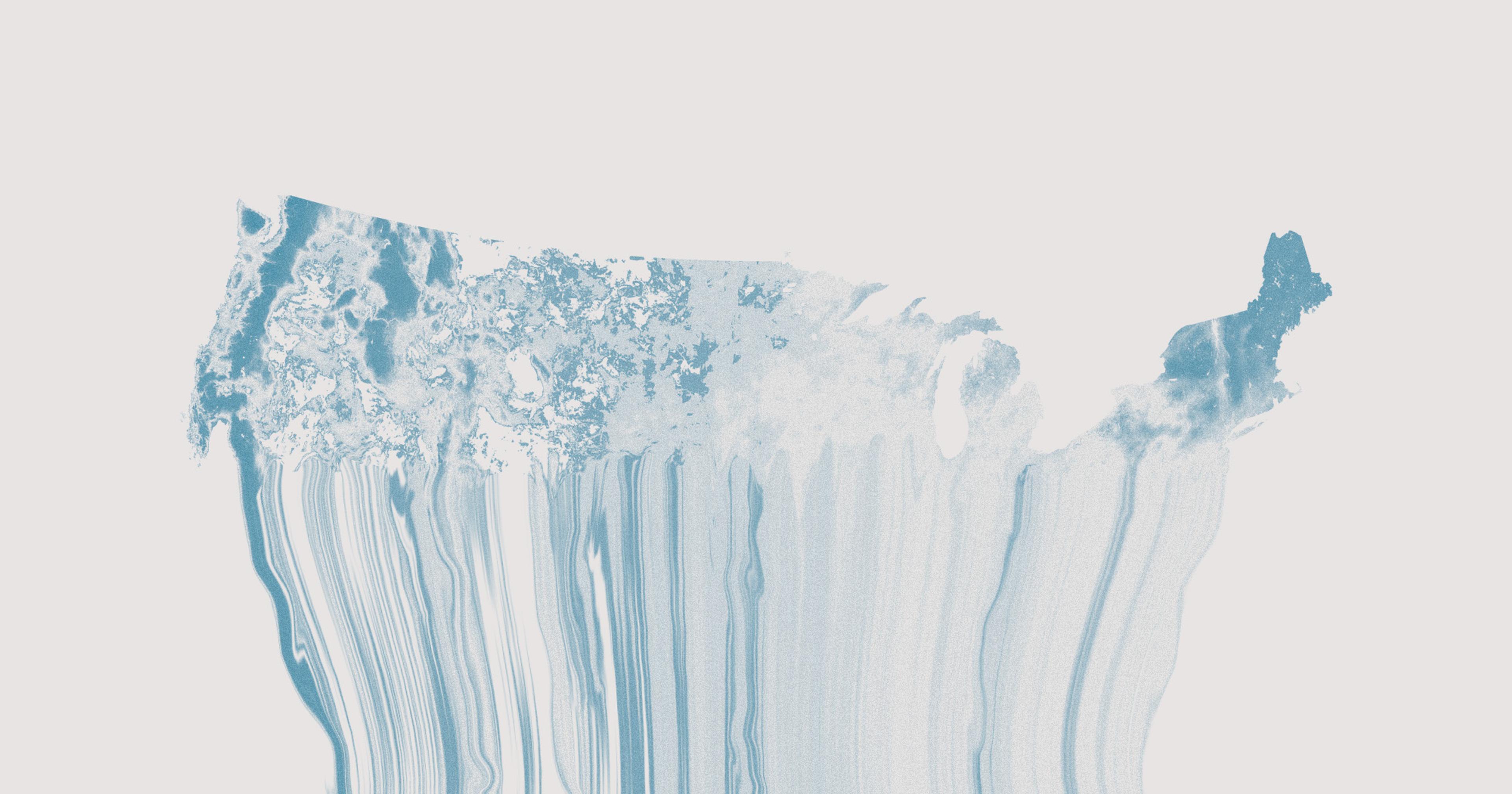

Multiple factors are at play in the unsustainable nature of how we use phosphorus. First and foremost, Grieger described the system as linear — meaning there is not a lot of recapturing phosphorus. For example, on a farm, phosphorus-based fertilizer is used in the field, but much of it is washed away by water. And once it’s out of the fields and into the waterways, it’s lost.

In fact, according to a study published in Nature Plants, it was estimated that less than 20% of the phosphorus applied in agriculture contributes to the food we eat. The remainder runs off from cultivated land and often ends up in aquatic ecosystems. That runoff can cause environmental impacts, like increased growth of algae and compromised water supplies. And for farmers, it’s a key resource literally washing away.

For an input that so many farms rely on, the phosphorus market is historically unstable. Not only is the supply finite, the suppliers aren’t abundant either. In the U.S., much of the available phosphorus is sold by just one company— leaving farmers and retailers limited purchasing options. Additionally, large amounts of the phosphate rock that’s extracted for fertilizer is mined overseas, the major producers being China and Morocco, meaning its pricing can be impacted by tariffs.

Additionally, that mining process can be brutal and requires clearing large areas of land. The mining and the subsequent fertilizer production process comes with significant environmental consequences, leaving wildlife displaced, changing the natural landscape, even producing radioactive waste leakage.

Despite this pollution potential, getting rid of it all together would greatly impact crops yields globally. While some farms stay away from chemical phosphorus fertilizers, and instead rely on natural sources of the stuff — like manure — the fact is plants need the nutrient to grow.

This leaves the industry at a standstill of how exactly to move forward.

“It’s a wicked problem.”

According to Paul Westerhoff, a regents professor of civil, environmental, and sustainable engineering at Arizona State University, “It’s a wicked problem.” He told Arizona State University News, “At one level, it’s an environmental pollution issue. But it’s also about the cost of food. Simply cutting back on the use of phosphorus in fertilizer could decrease crop yields and raise the price of almost everything at the supermarket.”

And in the meantime, farmers are left to deal with the consequences.

John Settlemyre, who operates a fifth-generation corn and soy operation with his family in Warren County, Ohio, was five days into the 12-day task of fertilizing his fields this spring when he found out the phosphorus order they were waiting on was no longer available. Settlemyre told Farm and Dairy that to keep going, his family was forced to switch to a different product that was available, which contained a lower concentration of phosphorus, and cost 25% more.

“It basically added about $35,000 to our fertilizer cost for this spring from that shift,” he said.

Market prices for phosphorus — and, in conjunction, fertilizers — have spiked significantly twice in the last two decades. In 2008, the prices soared 800% higher due to low inventory and high demand. Then, in 2020, in part due to the pandemic, there was a 400% increase in phosphorus commodity prices.

As conventional agriculture relies so deeply on phosphorus to produce crops, researchers for the study focused on the ag industry as one main group of stakeholders to survey. But because the reach of phosphorus is so great, identifying who to survey was complicated. The team ended up with a group that included the fertilizer, agriculture, mining, food processing, and chemical manufacturing sectors as well as policymakers, wastewater treatment facilities, and environmental groups.

“What we found is that there’s not a silver bullet solution, that there’s going to be a range of different possible solutions.”

“On one hand, you could argue that everyone is a stakeholder because phosphorus is a key component in the fertilizers that we use to produce food today. Our food supply systems and agricultural systems heavily rely on phosphorus,” said Greiger.

Because the resource is so crucial to the food system and overall life in general, many research projects are underway try and solve the phosphorus sustainability problem. Some suggest restoring wildlife populations to revitalize a natural cycle of phosphorus, while others dig into plant genes that could make crops more resilient to phosphorus deficiency.

But Greiger said this study is the first to capture the opinions of everyone involved in the phosphorus sector; it could serve as a stepping stone to actionable industry changes.

“To the best of our knowledge, our study is really the first that has actually documented … that these are the views of different stakeholders, and these are the challenges, and this is what we need to go forward,” said Grieger.

In the hopes of a more sustainable future for phosphorus, more than 50% of respondents reported that new, improved, or different regulations are needed, improved management practices and procedures are needed, and new technologies are needed.

“What we found is that there’s not a silver bullet solution, that there’s going to be a range of different possible solutions,” said Greiger. “And this study can be used to help identify research priorities and decision-making priorities moving forward.”