Sixty years after the last U.S. flax processor closed, the PA Flax Project set out on a mission to revive American linen. With a new mill finally opening, their plans are kicking into high gear.

When the last flax processing mill in the U.S. closed in the 1960s — a casualty first of cotton and then synthetic textiles — the nation’s centuries-old flax farming tradition faded with it. Now, a costume designer and a vegetable farmer have teamed up to help revive this field-to-fiber supply chain.

Heidi Barr and Emma Delong, co-founders of the PA Flax Project, have spent the last three years planting test plots; researching flax’s labor-intensive processing requirements; educating consumers; and networking with farmers, industry, and potential investors. Their goal is to recenter textile production on Pennsylvania farms, creating economic opportunity and reshaping the textile industry in the process.

“Flax for linen in North America is gaining a lot of momentum, and we’re one of the groups pushing it forward,” Barr said. With a new natural fiber processing facility opening in Southeast Pennsylvania later this year — the first to exist in the U.S. for six decades — the co-op’s efforts to produce a large-scale crop have kicked into gear.

Barr, a dancer turned costume designer, fell in love with flax when she began using deadstock linen to make napkins, tablecloths, and other household goods for her business Kitchen Garden Textiles. A mutual friend connected her with Delong, a farmer who was looking for someone to make a wedding dress. The dress never materialized, but the pair bonded over a shared love of linen.

“Within an hour of meeting, we started talking about linen as an agricultural product,” Barr said. In the early days of the pandemic, they planted their first flax crop by hand on a sixteenth of an acre of the poorest soil on Kneehigh Farm, the four-acre property outside Philadelphia where Delong grows organic vegetables and cut flowers.

Delong had experimented with growing indigo for dye, but this was her first time growing plants for fiber. “I was amazed at how we really did nothing” and got a usable crop, she said. “We made sure there was good soil-to-seed contact, and just let it go for three months.” As the project grew, she and Barr collaborated with Oregon-based organization Fibrevolution and received support from Pasa Sustainable Agriculture to help spread their message and connect with growers.

The strong, durable bast fibers, or phloem, of the flax plant — a long-stemmed flower with pale blue blooms — are the oldest textile in the world. Archaeologists have found twisted, dyed flax fibers that date back at least 30,000 years. Linen, the delicate fabric made from weaving spun flax into cloth, has long been valued for its breathability, softness, and antibacterial qualities.

Pre-colonization, some Indigenous groups harvested wild flax to make cordage, baskets, and fishing nets before Europeans brought cultivated flax to the continent. Colonial-era farm families, including the Germans who settled in Pennsylvania in the 17th century, typically grew their own flax, completed the elaborate process to transform the plant into fiber, spun the yarn, and wove the cloth to make garments and household textiles.

The strong, durable fibers of the flax plant — a long-stemmed flower with pale blue blooms — are the oldest textile in the world.

But flax’s status as the nation’s go-to plant fiber began to decline in the 19th century as cotton — with simpler processing and cheaper prices driven by the labor of enslaved people — proliferated. World War II-era government subsidies offered a boost, but flax couldn’t compete with new synthetic textiles in the postwar market. Farmers stopped growing flax, and the last U.S. scutch mill — where dried, partially decomposed flax plants are processed into soft, smooth fiber that can be spun into linen yarn or thread — closed in the 1960s.

“We have an opportunity that other groups don’t have, which is that Pennsylvania is getting a mill,” she said. “That accelerates our ability to push forward in phase one of our project, which is seed to harvest.”

Barr and Delong’s plan — to establish a farmer-owned flax cooperative and eventually a worker-owned mill — ramped up when they connected with Tarit Chatterjee, director of operations for Natural Textiles Solutions. The fiber processor, which has mills in Europe and India, was in the process of opening a facility near its corporate headquarters in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley. The mill, funded primarily with investment from sustainable textile company BastLab, will process hemp and flax into spinnable fiber.

As the company planned the relocation, Chatterjee began scouting for flax growers in the region. “We were looking for flax, but everything was about hemp,” he said. Chatterjee can’t commit to purchasing a crop until he’s sure it will meet the company’s specs, but all parties see the benefit of having supplier and processor so near each other. For now, Barr can point to Natural Textile Solutions as a source of demand for future harvests as she seeks funding. When the time comes, Chatterjee can source product from several growers through a single entity.

Today, flax in the U.S. is primarily grown in the Northern Plains for seed, not fiber; farmers harvested 268,000 acres in 2021. Around 80% of the flax grown for longline fiber, which makes the highest-quality linen, is cultivated in Europe, particularly Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. But extreme weather caused by climate change — drought in France in 2020, flooding in Belgium in 2021 — has damaged recent harvests, reduced seed stocks, and inflated prices for raw materials.

“We were looking for flax, but everything was about hemp.”

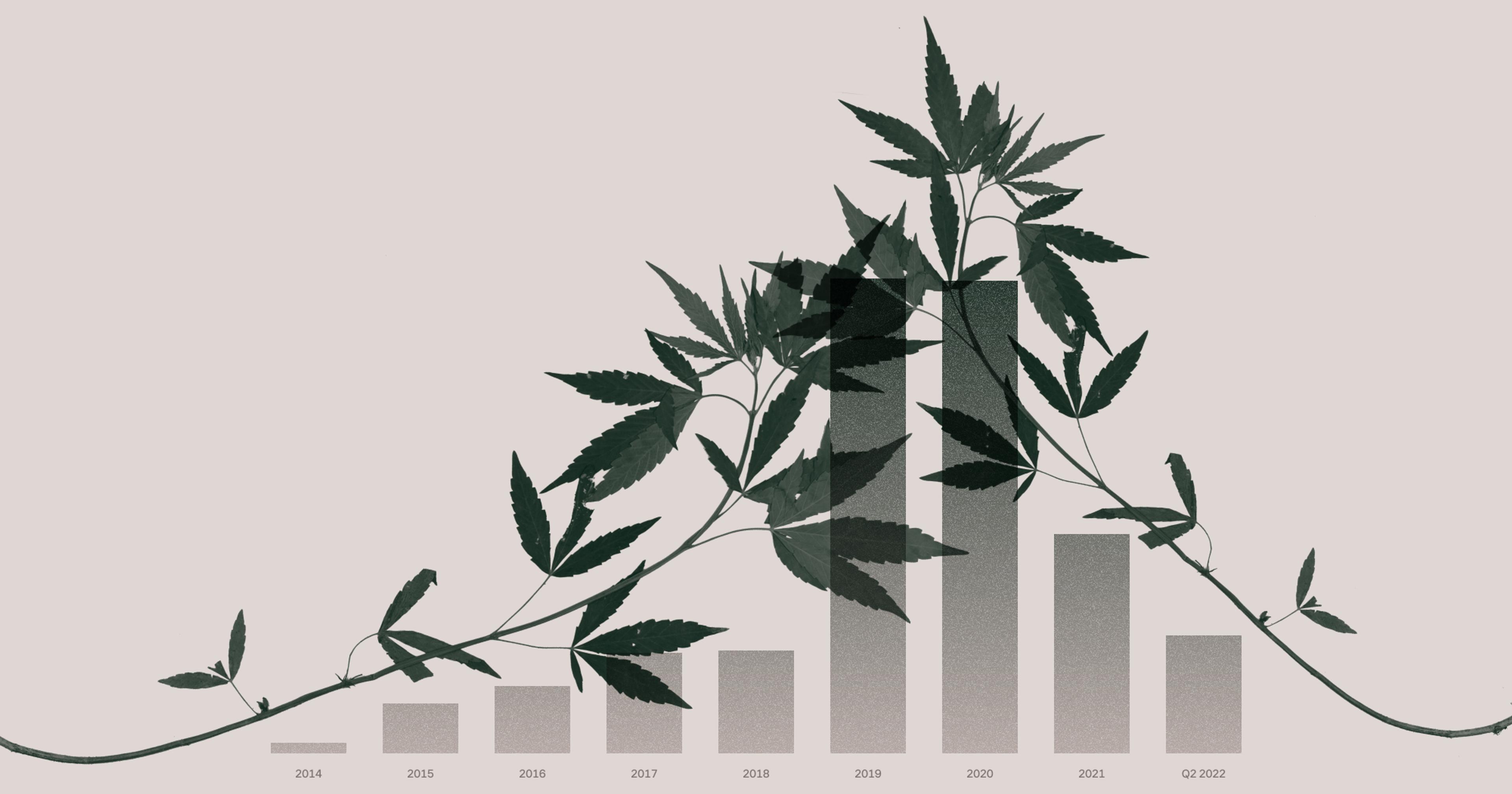

“It’s almost getting to a point where there are only specific geographical areas [in Europe] that can produce textile-grade flax, and that’s why we’re seeing higher prices,” Chatterjee said. He noted that demand for flax is higher than for other natural fibers because it can be made into finer textiles without the environmental footprint of raw materials like cotton and bamboo. The global linen market is expected to grow 11.2% through 2026, according to a 360 Research report.

In spring 2023, the PA Flax Project will trial 10 acres of flax, spread over several small and midsize farms eager to onboard with the co-op and scale up. Once growers have confirmed the crop can do well on their land and meet Chatterjee’s specifications, the co-op’s goal is to produce 5,000 tons of flax in the 2024 season.

The movement to revive North American flax fiber production, Barr noted, isn’t new. Advocates in the Pacific Northwest, the Midwest, and Nova Scotia have spent the last decade-plus laying the groundwork. Through the North American Linen Association (NALA), of which Barr is a board member, they’re sharing resources and combining their efforts to bring the crop and large-scale processing capabilities back to the continent.

The idea of reviving a supply chain that begins with fields of shimmering stems and ends with rustic tablecloths and summer dresses might seem like a romantic notion, but flax’s value proposition — for growers and for a more sustainable textile industry — is strong. It doesn’t require high fertility, irrigation, or pesticides, and co-products generated by processing can be used for everything from construction to horse bedding.

Flax is less resource-intensive to process than other natural fibers, and unlike synthetic textiles — which make up more than two-thirds of global textile production — linen is biodegradable. Reviving flax growing and processing could help reduce the 5% to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions attributed to the textile industry each year.

For crop farmers, flax can fit easily into a rotation with grains like corn, soybeans, alfalfa, and wheat. In the Mid-Atlantic, it can go in the ground as early as April 1 without ill effects from late frosts. Growers can harvest flax in early July, then plant spring wheat. And because the crop is pulled from the soil by the root, fields don’t require additional prep before the next planting goes in.

Once growers have confirmed the crop can do well on their land, the co-op’s goal is to produce 5,000 tons of flax next year.

Flax shares many beneficial properties with much-hyped hemp, including the potential to remove heavy metals like lead from contaminated soil. But hemp requires more nutrients than flax, and hemp fabric is coarser and less versatile than linen.

Flax also doesn’t come with hemp’s regulatory hurdles. “One of the benefits of flax is you don’t have to worry about permitting, testing, any of that stuff,” said Drew Oberholtzer, co-founder of Coexist Build, a producer of hemp-based construction materials. “It’s a different type of engagement with farmers, customers, the marketplace, and investors.” He’s working with the PA Flax Project to plant a half-acre trial plot on his fiber research farm in Southeast Pennsylvania this year and is eager to explore using flax’s co-products as a green building material.

“Flax could be a big benefit because it’s just getting shipped off the farm for a check,” said Jeremy Dunphy, owner of Pasture Song Farm, who grows corn, soybeans, hay, and small grains for his pigs, chickens, and cattle on around 160 acres near Delong’s farm. “If we could make that work in our region, it’d be a pretty big benefit to people’s rotations.”

But growing a crop for the first time and growing it well are two different things. While the PA Flax Project has half a dozen growers on deck, the USDA only offers crop insurance for flax if it’s planted as a small grain, not as fiber. The North American Linen Association is lobbying to change this, along with getting flax designated as a specialty crop in the 2023 Farm Bill. This year’s trials, and guidance from NALA’s grower training series, will give the co-op knowledge and tools to grow to Chatterjee’s specs with its founding members, then expand to other farms.

In the meantime, Barr is focusing on fundraising to cover admin and specialized harvesting equipment costs — and proving to the world that flax has a place on Pennsylvania farms. “The most inspiring thing about this is that it’s a very achievable solution to a huge problem,” she said. “Textiles were taken off the farm and brought into the oil industry, and this is a way to reclaim our textile agriculture.”