Rubber may be the most important agricultural product in America — and it’s in danger. Now, scientists and growers are working to cultivate solutions.

For more than a decade, Jody Scott tended shrubs in a dry field in southern Arizona. A lifelong farmer of myriad crops, Scott calls this the most boring thing he’s ever grown. And growing it, he said, “was the funnest job I ever had.”

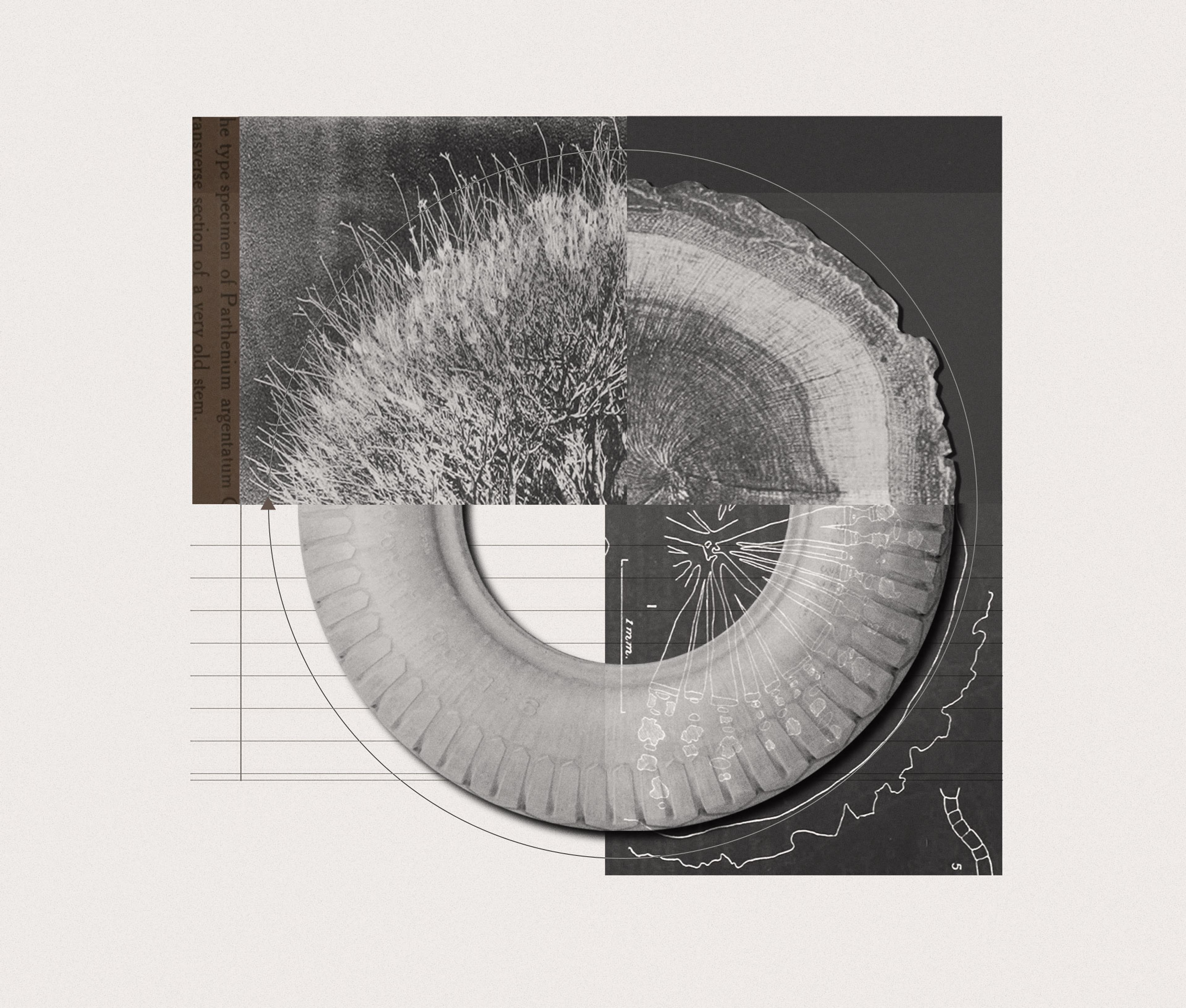

Guayule, (pronounced “why-you-lee”) is the shrub in question, a resilient native of the Chihuahuan desert. Its woody stems grow about two feet high and produce small, whitish-yellow flowers. It grows wild in parts of Texas and Mexico, but it’s also easy to cultivate and grow on farms throughout the region. Drought-tolerant and disinclined to disease, there’s not much that bothers it. “The only time this plant is vulnerable is when it’s really young,” said Scott. “Birds and insects think the seedlings are tasty, but once it gets up around six inches or so, it’s safe.”

In a range that stretches across the Southwest, Scott said, guayule may be the best erosion control method to “keep the ground from blowing away.” It’s good for something else, too: Grind those stems up and put them through a process of distillation and filtration, and the result is a high-quality natural latex that can be used to make everything from surgical gloves to car parts. This shrub, many believe, is the single best candidate for developing a domestic rubber market.

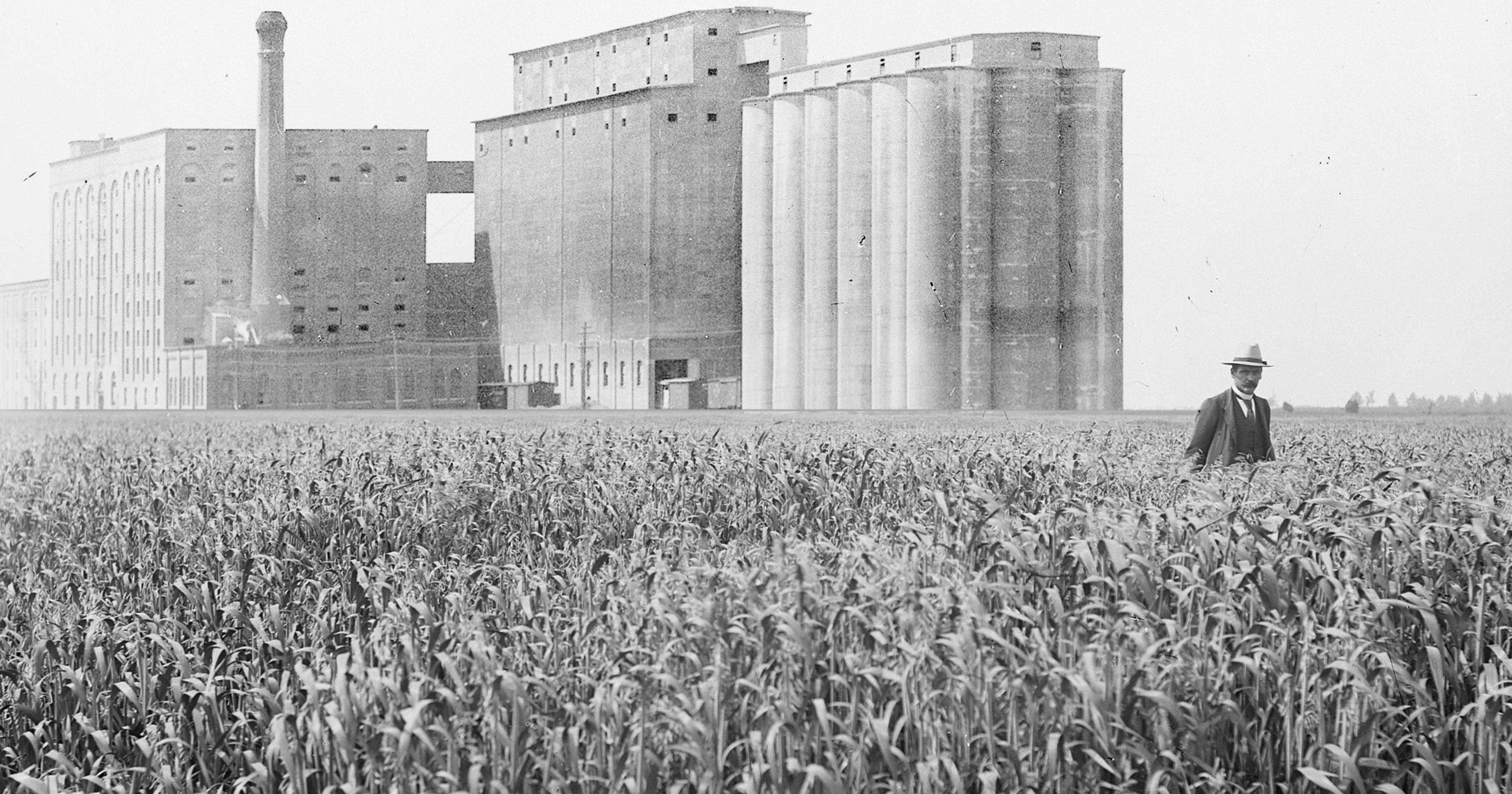

America consumes a lot of rubber. It’s used in the production of roughly 50,000 different products across manufacturing sectors; in addition to the 330 million or so tires made in the U.S. each year, it’s used for clothing and shoes, an array of household items and sporting goods, medical equipment, and more. And all of it — 1.5 million metric tons or more, worth $2 billion — is imported, mostly from Southeast Asian rubber plantations. But reliance on those foreign markets, and a single rubber-producing plant, could leave the U.S. market vulnerable. Now, scientists, farmers, and major corporations are working together to lay the groundwork for domestic rubber production, with plants like guayule at the center.

Rubber is a polymer made of latex, a substance naturally produced in the sap of a number of plants. Today, though, almost all of the world’s rubber supply comes from Hevea brasiliensis, also called the Pará rubber tree. Though it originated in the Amazon rainforest, native South American populations were largely killed off by an indigenous blight. Today, most rubber tree plantations are in Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

“There are 2,500 different plants that make natural rubber,” said Katrina Cornish, professor of horticulture and biological engineering at The Ohio State University, “but just by happenstance, it’s all ended up being commercially produced from one species.”

It’s largely shortsightedness, she believes, that led to dependence on a single species and a small growing region: Once a system of production using Hevea was established, there was little motivation to innovate further. But that, Cornish added, puts a nation like the United States in a perilous position. “I’ve spent 35 years trying to get people to understand the risk we’re taking by not being proactive about this,” she said.

“I’ve spent 35 years trying to get people to understand the risk we’re taking by not being proactive about this.”

Increasing global demand is straining the market, and disease poses an even bigger threat. If the South American leaf blight entered Asian plantations, it could rapidly cause catastrophic damage. And in recent years, another fungal infection called Pestalotiopsis has spread. Over the last six months of 2019, it damaged approximately a million acres of trees in seven countries. An estimated 10 percent of the global rubber supply was lost.

“The reason that didn’t just cause an earth-shattering panic across the globe was because that was when Covid hit,” said Cornish. “It closed down all the tire factories, which are the number one consumer of natural rubber. So, demand dropped by more than 10 percent.”

To Cornish, it’s long been clear that reliance on imported rubber, and a single line of cloned Hevea trees, is untenable. She’s the director of research for The Program of Excellence in Natural Rubber Alternatives (PENRA), a collaboration between a number of universities and private companies like Goodyear Tire. Her work centers on building a domestic industry and identifying the plants that could fuel it.

It’s necessary to find alternatives to Hevea, Cornish explained, for two reasons. First, the trees require a tropical clime, and have no frost tolerance at all. “You probably could find a few places in Florida, Hawaii, or Guam where you could grow it,” she said, “but there’s not a lot of suitable land or climate in the U.S. We’re really a temperate country.”

But the bigger issue is labor cost. “Rubber is hand-tapped,” Cornish explained. “A person goes out with a knife in the pre-dawn hours and makes a score in the bark of a tree, puts a cup beneath where [the latex] dribbles out, then goes back later in the day and collects it.”

“We’ve made bushings for Ford pickup trucks, every possible type of glove, condoms, surgical tubing, even animal balloons.”

The top wage for such workers in Southeast Asia is the equivalent of roughly $300 a month, she said. “You won’t find your average Floridian willing to work a grueling job, beginning at dawn, for so little.”

But other rubber-producing plants could be grown in the U.S. — not to mention planted and harvested mechanically, rather than with the arduous manpower required for Hevea — on a massive scale. Cornish’s lab has been focused on a species of dandelion and on guayule. The latter in particular offers a lot of opportunity for farmers, especially in parts of the U.S. that are growing more difficult to irrigate and cultivate.

“Agriculture in Arizona is getting pushed further and further out,” said Scott. “The absolute best soil and water in Arizona all has houses on it. Farmers are pushed out into regions I’m not sure even God intended to be farmed. It’s happening in Texas and California, just everywhere.” And competition for decent farmland, he said, is steep. “You’ve got to compete against alfalfa, corn, cotton, [and] produce.”

But guayule, with its lower water and fertilizer needs, is capable of growing in much less ideal conditions, and can thrive across a variety of geographies. Finnish company Nokian Tyres, for instance, produces a guayule crop in Spain, Cornish said. “It will grow in the Mediterranean, North Africa … South Africa loves it. You get fantastic guayule crops anywhere in South Africa that you put it.” In the U.S., its ideal range is only expanding as climate change pushes North America into an ever more arid future.

Perhaps most importantly, Cornish said, guayule produces latex and rubber that’s more than a substitute for traditional natural rubber: It’s better. “We’ve done lots of prototypes, and we’ve worked with lots of companies,” she said. “We’ve made bushings for Ford pickup trucks, every possible type of glove, condoms, surgical tubing, even animal balloons.” There’s widespread agreement among scientists and consumer product experts, she said, that guayule can create a superior rubber product. A big problem was getting it to produce at the same volume as Hevea.

“It’s an exciting industry because whoever gets this thing ironed out, I mean, they’re going to change the world.”

Recently, researchers in Cornish’s lab published a paper in the journal Environmental Technology & Innovation detailing a method that uses new flocculants — chemicals that separate latex particles from the other plant matter in guayule — to not only simplify the latex extraction process, but significantly increase yields. “You make a ‘milkshake’ and separate out the latex like cream from milk,” Cornish said. “What we found is a way to get twice as much latex as was possible before.”

Streamlining extraction essentially removes a last big scientific hurdle, she said. What’s next is about industry expansion.

“It’s all there, there’s just no processing infrastructure. We’ve got farmers who are willing to grow these crops and lots of companies wanting to buy the latex. We need a full-scale processing plant, and we’re looking at somewhere around a $70 million price tag.” Once it’s refined, Cornish added, rubber made from guayule or any other plant could be used — it could upend our entire rubber supply chain.

Scott’s hopes for the future of guayule and American rubber hinge on a visionary investor who might recognize the potential for a major payday. That person’s not likely to appear, he concedes, unless or until Asia’s Hevea plantations are struck by another calamity that drastically impacts global supply.

“It’s an exciting industry because whoever gets this thing ironed out, I mean, they’re going to change the world,” he said. “But until there’s a shortage, you’re not going to get anybody’s attention.”