If you’re a struggling producer without local mental health services, remote therapy seems like a promising option. But how do you overcome distrust of the unknown?

We’ve entered a therapy-friendly age: Online mental health companies ran ads during the Super Bowl and the Olympics, while a meme poking fun at people who resist counseling just went viral. It can be easy to forget that this is a relatively recent development, and that for many, therapy — and its attendant admission that all is not well — still carries a heavy stigma. This can be particularly true for older Americans, farmers, and rural residents (three groups with a lot of overlap).

In farming communities, “mental illness is not considered an illness. In many cases, it’s considered a character flaw,” said New York dairy farmer Jeff Winton, founder of the mental health nonprofit Rural Minds. “It’s considered a personality weakness.”

Winton speaks from experience — he founded Rural Minds after his 28-year-old nephew, also a dairy farmer, took his own life after years of suffering alone. Winton spends a lot of his time traveling the country, talking at Grange Halls and 4-H meetings, trying to encourage those in rural communities to seek the help his nephew never received. “We’ve got a lot of work to do,” he said.

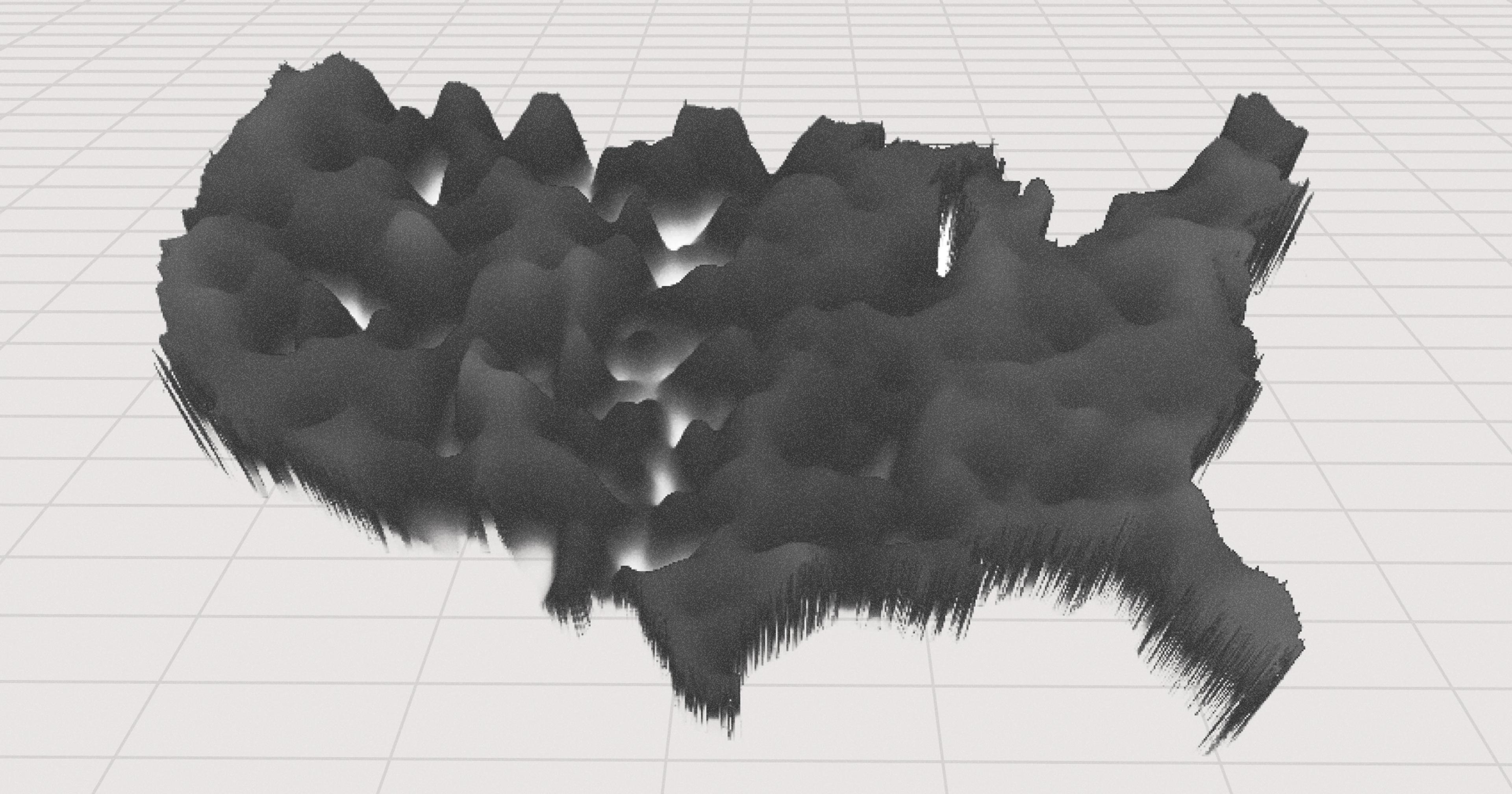

Research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that farmer suicide is up to 3.5 times more common than in the general population; they also suffer high rates of anxiety and depression. These findings may not be surprising, given deep-rooted challenges like rural isolation, farming’s immense financial and physical toll, and an all-too common resistance to seeking help. Alarming headlines on the topic have been commonplace for years; good news feels hard to come by.

Yet recent research across several arenas shows that online therapy is becoming an increasingly potent tool in combating the rural mental health crisis.

Cynthia Beck is a grain farmer and cattle rancher in rural Saskatchewan. She also has a master’s degree in clinical psychology — farmer mental health is highly personal for her. Beck recently undertook a study of 34 Canadian farmers who were suffering from significant mental health issues, engaging them in eight weeks of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT). The results were stunningly positive, surprising even Beck and her fellow researchers.

“Some of these folks told us that this was the first time they ever reached out for help, and they were dealing with severe, severe, severe anxiety and depression,” said Beck. “We saw clinically and statistically significant improvements for reduced depression, anxiety, and perceived stress. It’s really remarkable.”

Before digging deeper into the results, it’s worth noting how the study was set up, and what hurdles the researchers were hoping to overcome. First, there is a dearth of trained mental health professionals in many rural areas. If you’re a struggling farmer, already hesitant about receiving mental health services, the idea of spending hours in the car for a therapy session could make the notion totally untenable.

“Most of the therapists that people have access to are in cities, and have nothing in common with people like me and my family.”

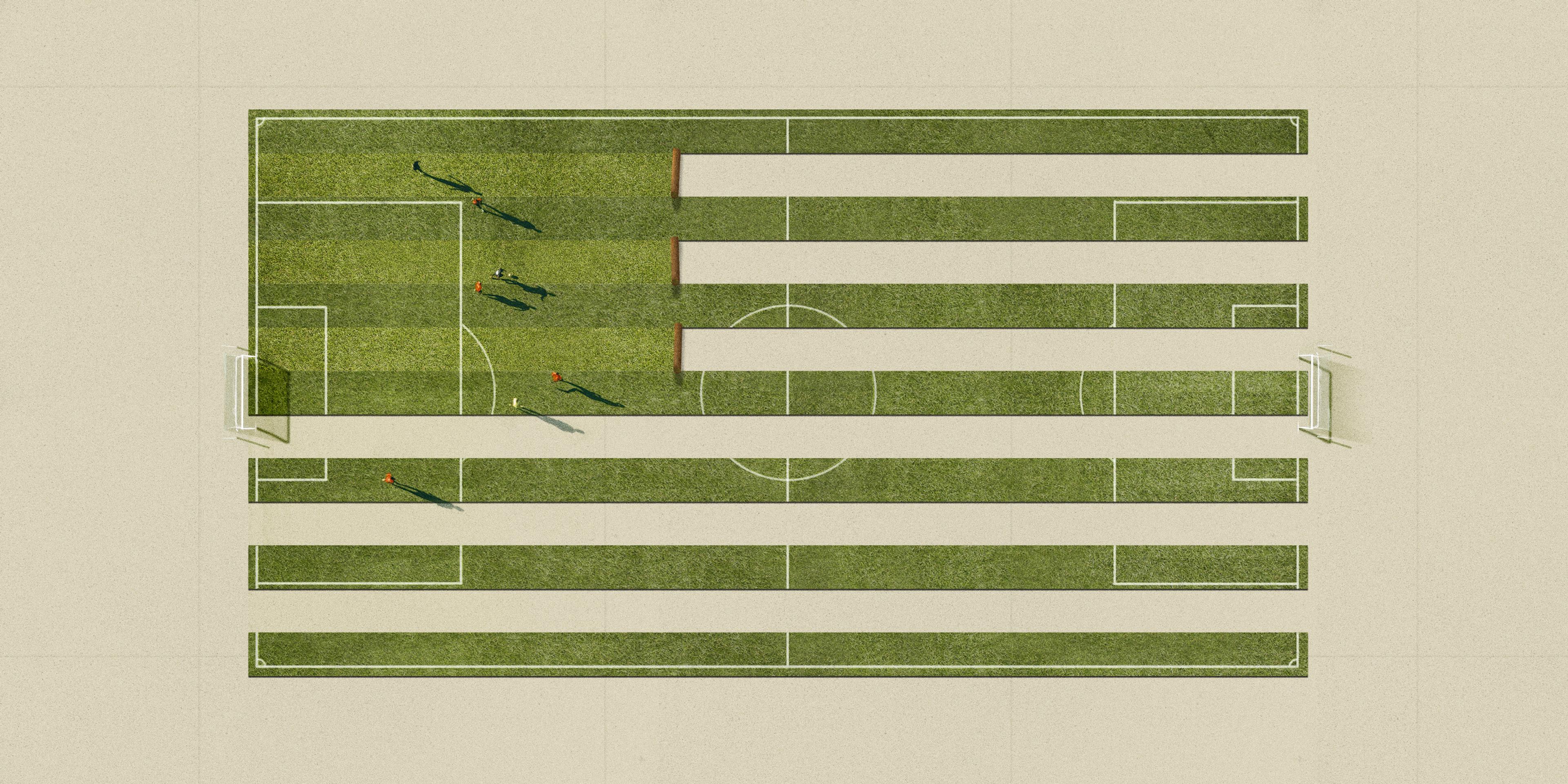

“It’s not only because of the cost of fuel for traveling and paying for the cost of the appointments,” said Beck, “but the cost of the loss you absorb because you don’t have somebody on the farm. Like during calving season, a producer will rarely leave the farm in case something major happens while they’re gone.”

Of course, the demands of this work can tie into the very reasons a farmer may be suffering to begin with. Jessica Beauchamp, a therapist with the Wisconsin Farm Center, said that being tied to your operation like that can take a significant toll. “You’re literally working 365 days a year. You live on the property, you look out your window and see the farm. You practically need a farmhand just to go get groceries,” she said. “There’s no break from it.”

Another benefit of online mental health treatments is anonymity. Considering the stigma still attached to getting help, visiting your small-town psychiatrist — assuming one exists — can feel like a vulnerable proposition. “I tell people that one of the best parts about living in a small town like mine is that when a tragedy happens, like what happened in my family, that people rally around and you have more tuna casserole than you know what to do with,” said Winton. “The flip side of that is if you have to seek help for a mental health issue, and your pickup truck is seen parked outside that therapist’s office, before you know it that news is going to travel like wildfire.”

That said, Winton also said a downside of online therapy is that rural residents, often suspicious of outsiders, may not warm up to the idea of pouring their heart out to a stranger. “They want someone they sit across the table from, someone they know and trust.” In particular, farmers tend to want someone who is familiar with the particular flavor of their challenges: isolation, financial precarity, vulnerability to the elements. “Most of the [online] therapists that people have access to are in cities, and have nothing in common with people like me and my family,” Winton said.

That’s why Beck created a farmer-specific guide to ICBT, which the two urban, non-farmer psychologists who helped conduct her study read in detail before providing treatment. It included facts about mental health and agriculture, and stories of recognizing signs of anxiety and depression in producers — Beck said it was a crucial element in establishing trust. “I [worked to remove the farmers’] preconceived perceptions that therapists without an agricultural background were not credible,” she said.

“The fact that they don’t have to leave the farm, change out of their clothes and get showered — they can just take a break from the skid loader for a bit. That is huge.”

Of course, technical challenges can also be a hurdle. Considering a large swath of U.S. farmers still don’t have access to reliable internet, online therapy can’t be taken for granted. Some of the participants in Beck’s study completed all eight weeks using only their cell phones — it worked, but it’s not ideal. “Without broadband, [online therapy] isn’t the panacea it is in urban and suburban areas,” said Winton.

And, naturally, despite the positive results in Saskatchewan, there will likely still be holdouts who resist the notion of online therapy. Monica McConkey, a Minnesota counselor who works with many farmers both in-person and online, said she insists her first sessions are face-to-face. “There are several advantages of in-person [treatment]. As a counselor it gives me better insight into what they are experiencing through their non-verbals such as body language, posture, eye contact, etc.,” she wrote in an email. “Another reason is that many farmers have hearing loss and struggle to read lips or understand what is being said virtually.”

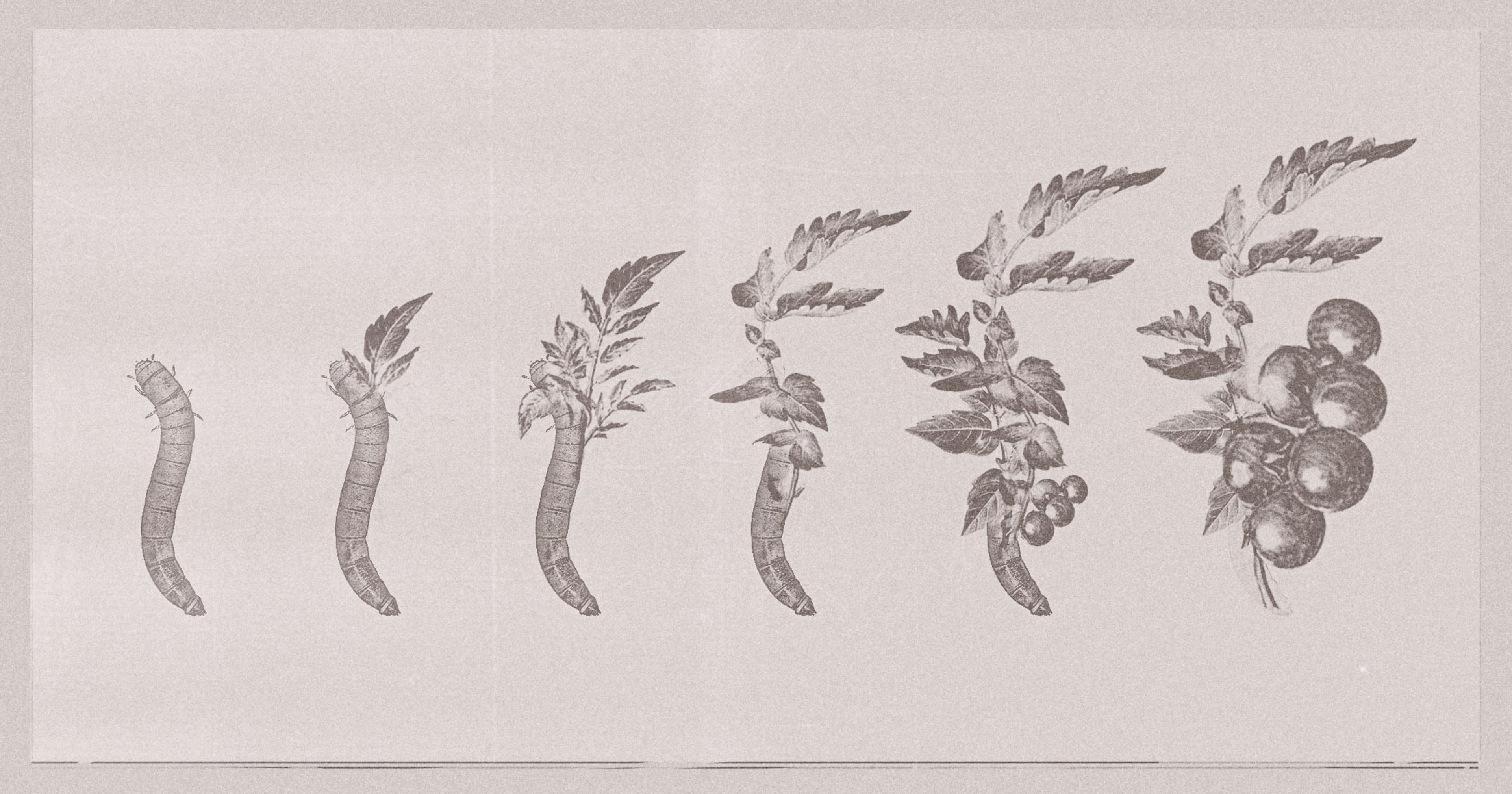

McConkey added there is a “disconnect and/or discomfort with navigating technology” among many of her older clients, leading many not to participate in online therapy. In his 60s himself, Winton thinks it may take years for a generational shift to take place, with younger people shedding the old prejudices against seeking help. Winton may be on to something: A 2022 study out of Tennessee showed that the stigma surrounding mental illness in rural areas may be lessening significantly, particularly among younger generations.

While online therapy is no quick fix to the complicated and urgent issue of farmer mental health, it’s surely a step in the right direction. Beck said that 100% of the farmers in her study believed that it was worth their time, and recommended it to other producers. One participant, who runs a large farm with multiple employees, got direct feedback from his staff that he seemed highly improved in just eight short weeks.

And Beauchamp, who provides online and in-person therapy out of the Wisconsin Farm Center, a state-funded community resource, said that she has seen more and more farmers attending her remote sessions. “I think it’s really changing everything,” she said. “The fact that they don’t have to leave the farm, change out of their clothes and get showered — they can just take a break from the skid loader for a bit. That is huge.”

If you or a loved one are struggling, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. Rural Minds also has a comprehensive list of rural-specific mental health services on its website.