As a range of legislation attempts to ban factory farming on a local level, it may not be so easy to define what we’re talking about.

To many, the term “CAFO” — or concentrated animal feeding operation — implies a certain kind of industrialized animal agriculture: massive operations controlled by a large agribusiness, with animals in cramped conditions and environmental impacts like the unrelenting smell of manure and the contamination of local watersheds. This kind of “factory farming,” as it’s often referred, has become notorious for horrific animal welfare conditions, pollution via the spread of livestock waste, and the economic collapse of rural towns.

As a result, it’s perhaps unsurprising that 54% of respondents told a Johns Hopkins survey that they supported a national ban or moratorium on new CAFOs. And this year, that fight is getting a real test — in November, voters in Sonoma County, California, will vote on Measure J, a ballot initiative that proposes to “stop factory farming.” To do so, the measure would ban CAFOs.

But the term “CAFO,” technically, is solely a water pollution regulation, governed by specific rules around farm size, animal housing, and wastewater management. Any farm with at least 700 dairy cows, 2,500 large pigs, or 55,000 turkeys that keeps the animals indoors for at least 45 days out of the year is technically classified as a large CAFO. These operations can pose a significant risk to their local communities if the waste from all those animals is released into the local environment — and many CAFOs, separately, have ties to large agribusiness and checkered animal welfare records. Yet, at least legally, the term CAFO has nothing to do with who owns the farm or how those animals are treated.

In communities across the country, people are now fighting back against the harms posed by factory farming, and many of these efforts focus specifically on CAFOs. But that term — factory farm — can mean different things to different people, depending on their priorities and interests. That contrast was apparent in a recent San Francisco Chronicle story about Sonoma’s Measure J. The story featured a local chicken farmer who sees his coops filled with birds as “his heritage,” where animals are “treated well” — and an activist who sees the very same farm as “inherently cruel.”

Everyone — from farmers and activists to politicians and grocery shoppers — has a stake in how food is produced. And everyone bears the consequences of the environmental, welfare, and economic impacts of industrial agriculture. But if you want to start making policy to address these challenges, finding some sort of consensus on what (and who) the problem is starts to become important.

“A term like ‘factory farm,’ it’s very difficult to enact policy on a term like that, so it really needs to be defined,” said Jonathan Coppess, associate professor of agricultural policy and law at the University of Illinois. “And then when you start defining it, the complications are pretty significant.”

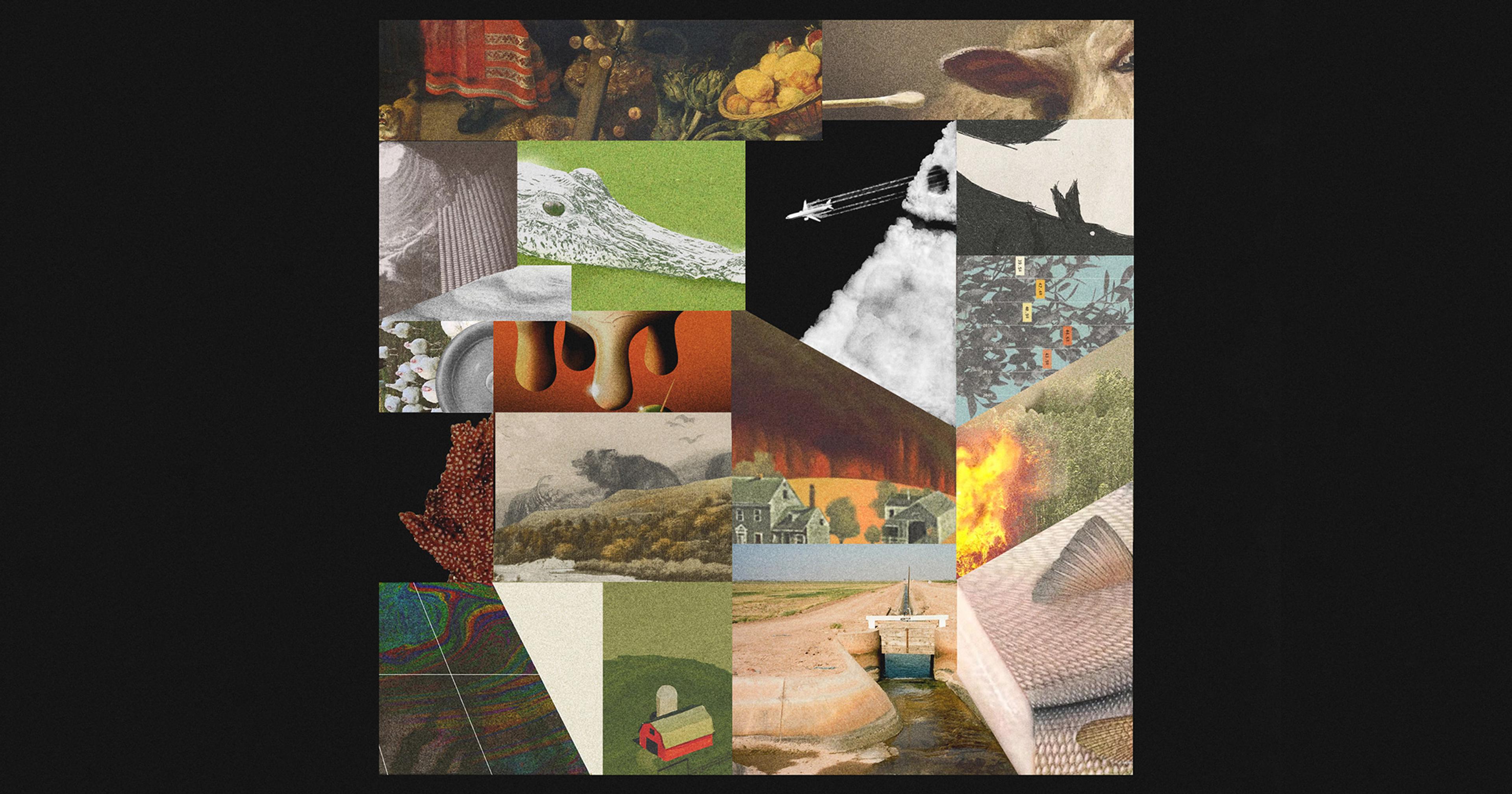

Factory farming can be viewed from a lot of different angles. From an animal welfare angle, you might call it a factory farm if the animals face inhumane treatment or intense confinement. From an environmental angle, it might be a large farm that poses a significant source of water pollution or odor. And from an economic angle, a farm could be a factory if it’s not owned and operated by a family, but rather a large agribusiness. But these descriptors don’t necessarily correlate with each other.

“A term like ‘factory farm,’ it’s very difficult to enact policy on a term like that, so it really needs to be defined.”

Take farm size and animal welfare — you can have a large farm that treats its animals well and a small farm that treats its animals poorly. In a 2019 article, a group of animal welfare experts at the University of British Columbia pointed out that larger farms may come with a reduced risk of lameness in cattle. But they also noted that large farms can come with welfare risks, such as being less likely to let their animals feed outside on pasture. Amy van Saun, senior attorney at the Center for Food Safety, made a similar point. “When you get that big, it’s not possible to have pasture animals,” van Saun said.

Many “factory farms” are either owned outright by an agribusiness or contracted out to individual farmers, who can struggle under these agreements and have little say in how they run the operation. But, large, industrialized farms aren’t necessarily owned by a big corporation. In fact, many aren’t. “You can have a family farm by the most traditional definition of family farm, a couple generations, possibly even, in the operation,” Coppess said. “But they are thousands and thousands of animals under one confined facility. That’s not at all uncommon.”

Any farm with thousands of heads of livestock, whether owned by a family or a corporation, does come with environmental concerns. More animals mean more waste, and larger operations that confine their animals indoors are categorized as CAFOs out of concern about all that waste. These CAFOs are supposed to be permitted and regulated with nutrient management plans to deal with that waste and limit pollution (though many slip through the cracks).

These different conceptions of factory farming may impact how policy and political fights on these issues play out, such as with the Sonoma County ballot measure. While activists in favor of the measure have stated that they’re focused on CAFOs (and claimed that such a move would help small farmers by improving their competitive advantage), some farmers in the area have worried that such a move would eventually impact other farms. Some environmental and family farm advocates have also expressed concerns that, in their opinion, this measure may not be the best method of addressing the concerns around factory farming.

But when you ask family farmers and family farmer advocates how they define a factory farm, they often have a pretty good idea of what counts. “When I raise these hogs, do I get to decide how many I raise? When I raise them? Where I raise them?” said Berleen Wobeter, who lives on a farm in Iowa. “Or is someone else saying: ‘You do everything I want and then we’ll buy them?’”

“When I raise these hogs, do I get to decide how many I raise? When I raise them? Where I raise them?”

Jenna Vanhorne, a dairy farmer from North Dakota, echoed this sentiment. To her, a “family farm” wouldn’t have a board that tells them what to do — rather, the family makes the decisions and invests in the future of the farm until they’re ready to pass it down to the next generation. Factory farms, on the other hand, are operations that are “just pushing animals through” and have “a lot of capital and backing to make it work,” Vanhorne said.

Farmers, when asked about factory farms, also brought up specific operations near them. Wobeter noted a 5,000-head hog CAFO that had previously been proposed on a five-acre plot in her community. “It was just a very scary situation because our lives could have changed completely with the smell of hogs all the time, windows closed at night, no fresh air, new trucks on our roads that aren’t the best shape as it is because they’re gravel roads,” she said. “And what does our community get out of it? Very little.”

Blake Naze, a livestock farmer whose family has been in North Dakota since the mid-19th century, also questioned whether the people running some of these larger operations contribute to the local community nearby, send their kids to the local schools or help with local challenges.

“That’s what rural America was built on,” Naze said.

For many, “factory farming” seems to be about the antithesis of that ethic — the sense of belonging, mutual well-being, and camaraderie in an agricultural community where neighbors support each other. Are you buying supplies from the local supply shop, or shipping them in from out of state? Are you treating your animals, as van Saun put it, like sentient beings with social behaviors and emotional needs, or like “widgets?” Are you operating your farm with an eye toward a sustainable, prosperous future for your family and your neighbors’ families, or are you trying to maximize profit at all costs?

Each of the concerns associated with the term “factory farm” — environmental, animal welfare, corporate consolidation, etc — could be addressed with individual policies and programs focused on those concerns. In recent years, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) has introduced several proposed laws aimed at some of those concerns. The Farmland for Farmers Act, for example, would place limits on corporate ownership of farmland, and the Industrial Agriculture Accountability Act would, among other things, improve animal welfare conditions at processing plants.

Wobeter also said bringing back small processing plants could help smaller-scale farmers by giving people with just a few animals a place to get their meat processed. And Jordan Treakle, from the National Family Farm Coalition, noted that many programs to help independent farmers with conservation, water quality and animal welfare — such as the Conservation Stewardship Program — haven’t kept up with the demand from farmers.

Together, these sorts of efforts could make it easier for farmers to make decisions for themselves on how they want to raise their animals. They could also make it harder to farm in a way that harms animals, local environments and agricultural communities — breaking down “factory farming” not through one fell swoop, but through a death by a thousand cuts.

But if you truly need a concise, holistic, definition of “factory farm?” Well, it may be best defined much the same way that Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once famously defined another hot-button issue: You know it when you see it.