How ranchers prepare cattle to sustain extreme temperatures and winter storms.

Nearly a decade ago in South Dakota, an early October winter took cattle ranchers and their herds by surprise.

Snowflakes spun so violently in 70-mile-an-hour winds that some cattle suffocated. Four feet of snow caused cows, still wearing their summer coats, to get caught up by snow drifts. Freezing rain coated rocky cliffs with ice, and cattle slipped. Some simply froze.

The results were catastrophic.

The unexpected storm left so many cattle dead that the state’s then-governor, Dennis Daugaard (R), issued an executive order that circumvented the weight limits for truckers who hauled dead cattle carcasses off of ranches, to speed up the process. The early blizzard ended up taking the lives of around 20,000 cattle and costing ranchers collectively tens of millions.

That nightmarish scenario is what every rancher hopes to avoid. With livestock like grass-fed cattle, which are often outwintered — left outdoors for the cold months — ranchers need to be prepared to help herds survive extreme cold, snow, and other winter weather woes.

Staying Prepared

When it comes to keeping cattle alive in the cold, preparation is key. That makes early-season storms the most deadly — particularly those that arrive without warning. Without time to grow winter coats and gradually acclimate to dropping temps, Paul Beck, associate professor of animal and food sciences at Oklahoma State University, said cattle are at their most vulnerable. “Cows are much more resilient to weather when they have a heavy winter coat. Cows with a summer coat, shortly after we’ve had warm weather, are at the most risk to be the first storm victims,” he said.

Non-farmers may pass by herds of cattle braving cold weather without winter outwear — like the blankets sometimes seen on horses — and feel badly for them. But the right nutrition and shelter are all cattle require though the winter months.

When they have had time to ease into cold weather, cattle are extremely hardy creatures — ask any rancher. The cows’ thick winter fur, alongside their anatomy — a digestive system that acts as an internal fermentation chamber to generate heat — allows a good deal of cold tolerance.

A cow’s lower critical temperature, or the coldest it can handle without added calories to burn, rests right around 32 degrees F. To get cattle to tolerate colder temperatures, ranchers must increase their food supply to ensure they have enough sustenance to generate heat. Beck explained that for every degree colder than a cow’s critical temperature, it requires a 1% increase in energy to survive the cold — the colder it gets, the more a cow needs to eat.

In extreme cold, cows are burning through nutrients fast to keep up their core temperature.

At a certain point, say it’s -30 degrees F with windchill, there will be a limit to how much feed a cow can physically eat. This solidifies the importance of supplying cattle with supplemented nutrient intake before and after the height of a winter storm or a rapid drop in temperature. This is the case for all cattle, whether they are grass-fed only or grain-fed. For grass-fed cows that graze during warm months, ranchers supply hay when the ground is covered with snow and ice.

But it’s not just how much the cattle consume — quality is key.

In extreme cold, cows are burning through nutrients fast to keep up their core temperature. Without the right balance of protein and other energy sources provided by high-quality hay or feed, even a cow with a full stomach could suffer. “You have to be careful with quality,” said Joe Armstrong, cattle production systems extension educator at the University of Minnesota. “If you feed poor enough quality hay … you can have an animal be physically full and they can still starve to death.”

Shelter From the Storm

In addition to dietary preparations, ranchers have to focus on how to set up places for cattle to find refuge from winter winds, snow, and ice storms.

In the Blackfoot Valley of Montana, Logan Mannix and his family spent frigid weeks in December making sure their herd of around 400 grass-fed cattle could survive the cold. The state experienced a week in late December with temperatures that dropped lower than -40 degrees F with windchill — the coldest weather the region had seen in nearly three decades. Luckily, the Mannix ranch had enough warning and were able to set the herd up for success.

“We moved several herds into our most sheltered pastures and bale-grazed one of those groups there and they came through the storm just fine. We didn’t lose any of that we know of due to the cold,” said Mannix.

“Just like people, if they’re wet, it’s going to make the cold even worse.”

To survive winter, cows need windbreaks to shelter them from icy gusts as well as warm, dry places to rest, called bedded packs. Armstrong said it’s important to offer the cows a spot as dry and shielded as possible to seek shelter. “If it’s going to be really cold, we need a spot for [the cattle] to lay down that’s clean and dry. Because, just like people, if they’re wet, it’s going to make the cold even worse.”

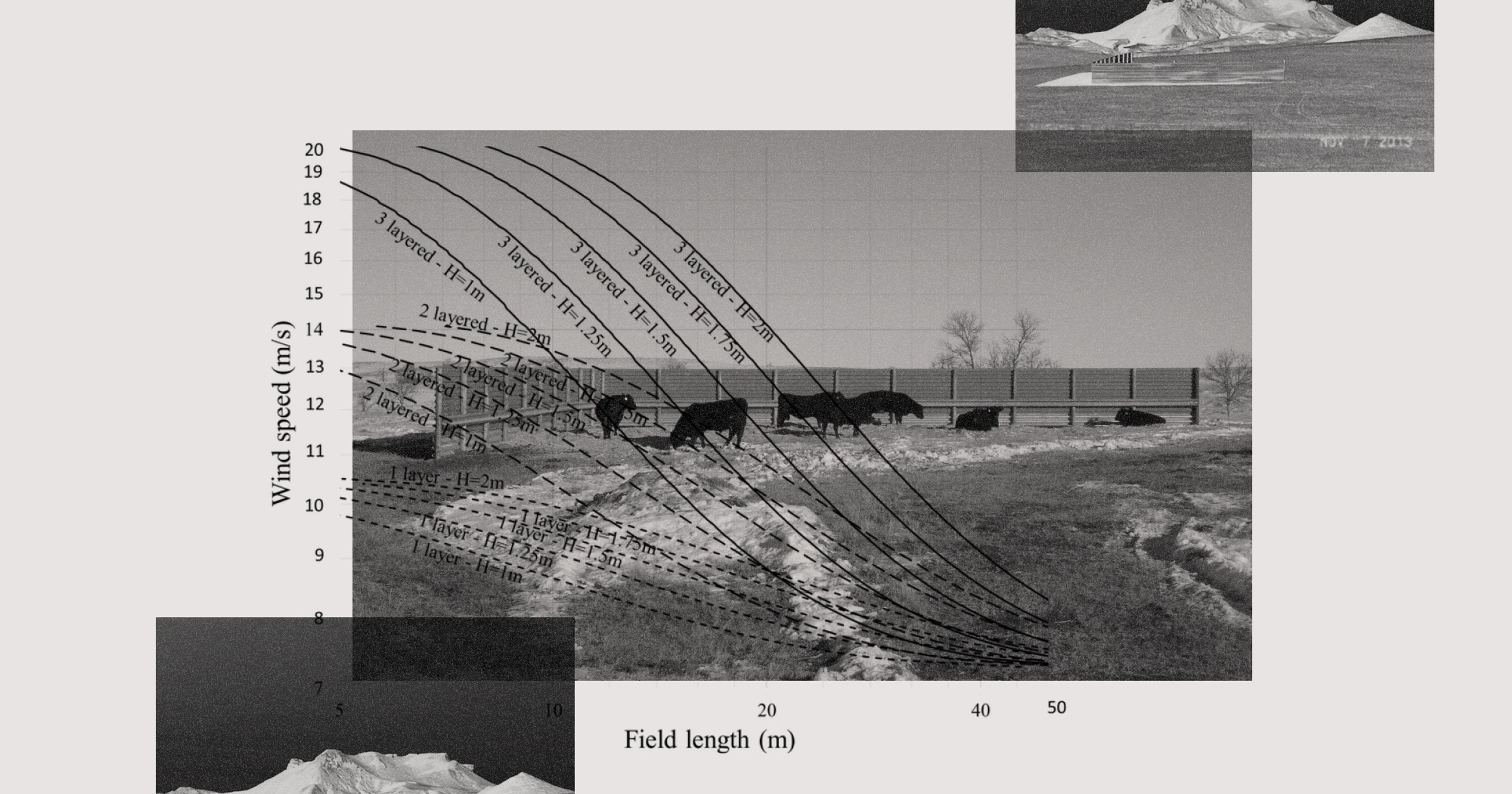

Usually made of straw or corn stalks, bedded packs are deep piles of the bedding material, with a dry, fresh layer added daily. While trees or buildings can act as windbreaks, ranchers also build their own. Effective windbreaks need to be tall structures that let small amounts of air through to avoid downward drafts as the wind passes over.

When preparing cattle for incoming cold, centralizing their resources and shelter to keep cows from straying is a key to keeping them alive. Keeping the packs sheltered by the windbreak is the most successful way to shelter herds in winter. Water and food should be placed behind the windbreak to encourage cattle to stay close to the shelter.

Complications Abound

Water is another complicating factor, as it is difficult for ranchers to keep tanks from freezing up in the cold — owners are often left checking water systems multiple times a day in extreme temperatures. Fortunately cattle are crafty — Mannix said they can survive for a while even without getting their water provided.

“A lot of cattle won’t travel to water during those storms. They’ll get by on snow for quite a while. So a lot of times, you’ll see that even if you keep the water open in the storm, they just huddle up and eat some snow and hay. Then when it clears up, we’ll see them visit the water tank again,” he said. This, of course, is only an option in snowy conditions. Dry, extremely cold weather leaves ranchers responsible for keeping a close eye on water tanks to ensure they don’t freeze over and leave the cows thirsty.

Even with an all-inclusive area set up for the cattle, Mannix said it’s still the best practice to fence off potentially dangerous bogs, streams, and other water sources. Confusion caused by cold-induced stress can lead a cow to wander, so it’s important to keep cattle away from icy waterways, in case they attempt to walk across thin ice and fall through.

In winter weather, cattle can enter cold stress — when their coats and natural metabolic process are no longer enough to keep them warm and their core body temperature drops. This stress can cause cattle to change their behaviors, leading cattle to seek out shelter, which, if not provided, can lead to issues. In the past, said Mannix, the ranch has lost cattle to cold snaps thanks to this cold-stress-induced behavior. Although the ranch has avoided it so far this year, wandering cattle have broken through the ice of streams or springs, ultimately leading to their deaths.

The choice between personal well-being and caring for livestock can prove difficult for many ranchers.

Snow drifts offer another potential winter death trap. Mannix said snow drifts have been known to endanger cattle and ranchers. “I’ve heard stories of cattle being killed when they seek out a draw or something like that for shelter, and then are drifted in with snow. Or when ranchers were so drifted in that they couldn’t get to the cattle to feed or water them,” he said. Fencing off and avoiding areas of a field at higher risk for drifts can help with this issue.

Throughout all the thought and effort ranchers put in to maintain their herds’ health through the cold, Armstrong noted the hardest part is often getting the ranchers to prioritize their own well-being in extreme weather.

Cold stress isn’t unique to cattle. Even bundled in layers to keep in body heat, ranchers risk hypothermia, frostbite, and other health concerns themselves when facing extreme winter weather. In a perfect world, said Mannix, “you feed the cattle and get them tucked in before the worst part of the storm hits.” But reality sometimes leaves ranchers outdoors tending to herds in high winds, fierce blizzards, and frozen rain. The choice between personal well-being and caring for livestock can prove difficult for many farmers and ranchers.

“People have such a strong connection to their animals, and they feel a huge responsibility to take care of them, and they should,” he said. “At some point, if the weather’s bad enough, you have to prioritize your own safety. And that’s something that ranchers have a hard time stopping and thinking about before they race out to take care of their animals.”