Thousands of miles from home, Somali refugees in rural Maine have begun to thrive thanks to a cooperative community farm.

Throughout Maine’s growing season, over two hundred Somali Bantu families travel the state’s winding back roads to the tiny town of Wales. They bus and carpool back and forth from the urban center of Lewiston, 20 minutes away. Their destination is a 103-acre farm of rolling hills, covered in waving stalks of flint corn. As this year’s season comes to its close, Muhidin Libah sits in the farmhouse surrounded by seedling catalogs, planning the farm’s crops for the next growing season.

Many of the crops grown at their Maine farm are familiar to the immigrants from their farms in Somalia, although their cultivation is modified to accommodate Maine’s shorter growing season. “In Somalia we grew yams,” Libah explained, gesturing to where a list of the farm’s crops and profits from the previous season cover one kitchen wall. “We grew all kinds of tomatoes, hot peppers, bell peppers. Swiss chard was wild in Africa; we never grew Swiss chard but we had it as a wild plant.”

Maine holds the dubious distinction of being one of the whitest states in the U.S. As of the 2020 Census, 90.8% of Mainers were Caucasian; it is not unheard of for a Maine child to grow up without meeting a person of color. So when the Somali Bantu community began to arrive in the Lewiston area in 2001, some Mainers did not welcome them with open arms. In 2002 the mayor of Lewiston wrote an open letter to Somali immigrants asking them to stop coming to his city. In 2006, a severed pig’s head was thrown into a mosque in Lewiston.

While many in Maine did embrace the arrival of the Somali refugees and supported the community in the face of this hostility, many still wondered: Isn’t Maine awfully cold for people from an African nation? Why would they want to live here of all places?

Maine was attractive to Somali immigrants for the same reason that it appeals to transplants from Washington, D.C., or California. The state has a low crime rate, good public schools, and affordable housing. Somali immigrants believed that Lewiston would be the best place to restart their lives.

“Lewiston had a bias,” explained Libah, executive director of the Somali Bantu Community Association (SBCA) of Maine, “They had a myth, saying that ‘Oh these people are coming to Maine because of the welfare system.’”

“They had a myth, saying that ‘Oh these people are coming to Maine because of the welfare system.’”

Somalia has been a country of conflict for generations, its current civil war raging since 1991. The Somali Bantu, a minority ethnic group, are a subsistence farming population who live in small villages. The Bantu are a peaceful people whose settlements are often destroyed in the conflicts of other ethnic groups.

Libah arrived in Syracuse, New York, from Somalia in 2004, after growing up in Kenyan refugee camps. A proficient English speaker, he was able to understand the complex forms and paperwork of this new country, leading to requests from refugees in Lewiston to help them organize and form a group to help support each other.

“I started loving Maine,” he admitted. “I started staying longer, bringing my wife with me — and she loved Maine, so she said you know what, we are moving.”

The displacement of the Bantu people in Somalia eventually led to the resettlement of Bantus across the United States, including the large settlement in Lewiston, Maine. Today there are over ten thousand Bantus in the small Maine city, whose overall population is just 38,493.

“The Bantus are land cultivators, they grow food,” said Libah. “They may have a sheep or a goat or a cow, but they are not animal rearing communities. We live in permanent settlements, we don’t move. On the other side, the people who are now the powerful people in the country are the camel herders, cow herders, and goat herders.”

Libah helped to found the Somali Bantu Community Association to help refugees resettle and understand how to live in the United States. The first challenges were teaching Somali immigrants how systems worked within the U.S. “In Somalia you have a simple life,” Libah said. “You don’t have to pay for anything, if you need land you just go to the chieftain and he assigns you a piece of land, and it is yours forever.”

“They said farming, farming, farming. We need a piece of land to farm, we need to farm.”

When he asked the community what they needed, the answer was universal.

“They said farming, farming, farming. We need a piece of land to farm, we need to farm.”

The Somali refugees had largely been relocated to urban areas such as Lewiston, even though their culture is one of land cultivation and agrarian lifestyle. The act of farming reminded the Somali Bantu refugees of their homeland and the lifestyle they lived before their world was torn apart by war. It also gave them control over their food source.

“Think about the refugee resettlement process and what that means for an agrarian culture,” Ashley Bahlkow, a program adviser for the Somali Bantu Community Association, told Katy Kelleher for Down East magazine, “It’s resettling folks with few resources and in urban settings, because that’s where some of the few resources we do offer exist, like public transportation.”

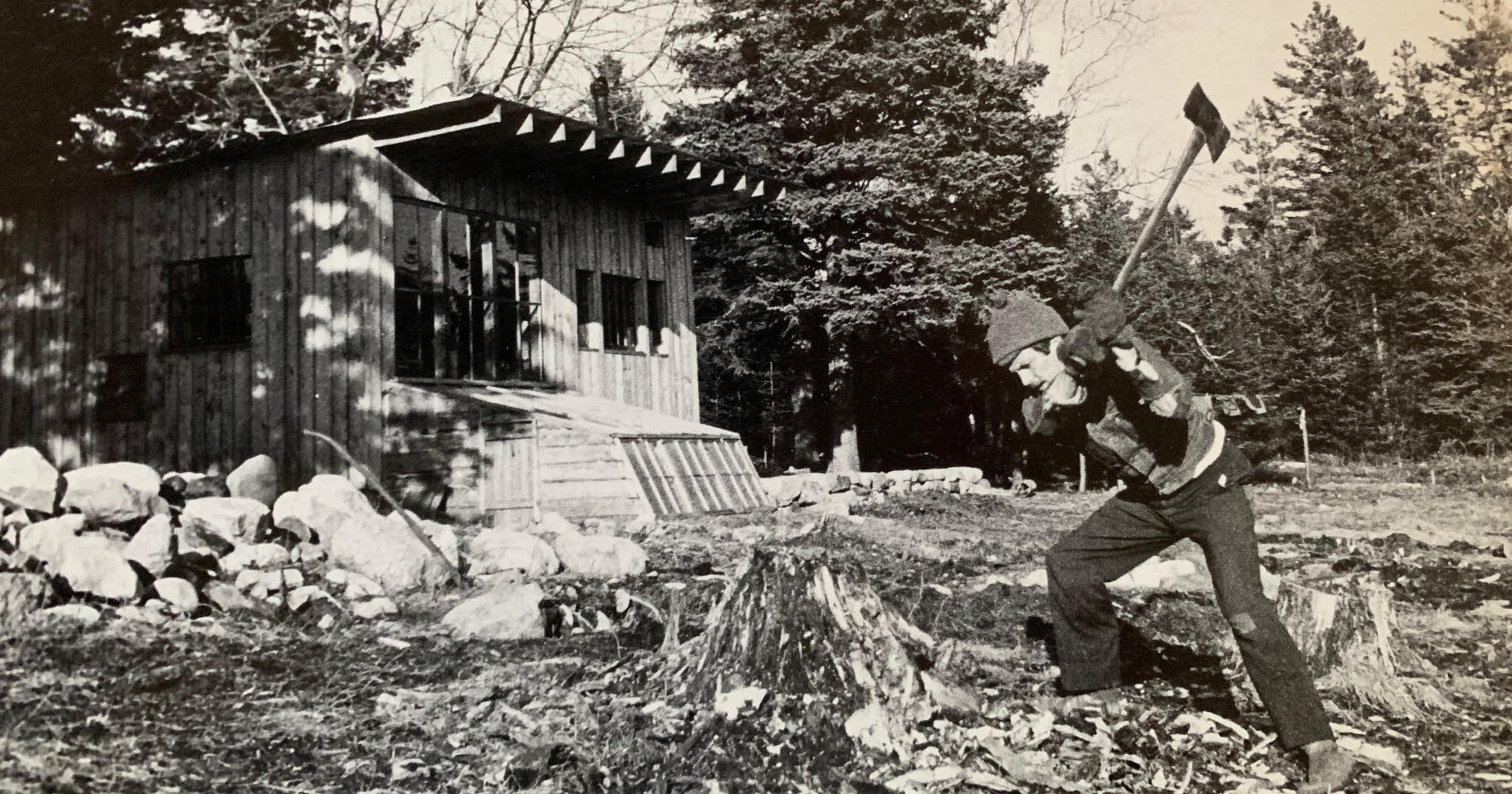

Libah set about trying to find farmland. In 2014 they were able to lease a small plot of farmland in North Yarmouth, Maine, enough to accommodate 20 farmers. The next problem was what to grow.

“I was scrambling just to get some seedlings, doesn’t matter what kind,” remembers Libah. “But I did not know that people had corn seeds in their luggage from Africa. I saw something sprouting, coming out of the ground, and I said what is that? That’s corn, they said, from Africa!”

That first year, the developing farm operation grew African flint corn or maize, a crop that can be eaten or ground down to make flour. Soon they found more land to lease, and were able to accommodate 42 farmers in a plot in the nearby communities of New Gloucester and 36 more at a farm in Sabattus. But all of the driving was taking its toll.

“It was driving all day long, just to see what is going on at the farm,” said Libah. Because they were leasing the farmland, rather than owning it outright, they were unable to add infrastructure such as a wash station to prepare their produce for market. They were also unable to amend the soil — often necessary for a successful crop in Maine’s mixed terrain.

After years of moving from one farm to another while searching for land, the SCBA was finally able to sign a 99-year lease in Wales. The new farm could accommodate all of the interested growers in the Somali community. With this acreage, Libah has been able to offer land both to those wanting to grow for themselves and those interested in growing for market.

Muhidin Libah gesturing over the fields of Liberation Farms. Photo by Kelsey Kobik.

·Habiba Salat showing off harvest of Swiss Chard & greens. Photo by Somali Bantu Community Association.

“One portion is the community garden,” Libah explained as he walked across the sloping terrain of the land they have named Liberation Farms. “We prep the land, divide the land, and we put names on the stakes. People will come and access the land. Everything they grow we have no control over, they produce whatever they want, and they take it home. If they have more than they can consume, they can contact us and we sell it for them.”

But Libah is most proud of the cooperative growing system at Liberation Farms. There are 45 farmers who are part of the cooperative, which grows produce to be sold in their farm stand and at local farmers markets, as well as corn that is used by a host of companies along with the community’s own flint corn tortillas sold directly across the state of Maine.

Growing in Maine is challenging even for farmers who have grown here their entire lives. The Somalis admit that 2023 was a rough season; unusually high rainfall damaged some of their corn crops.

“We never had to amend the soil back home in Africa,” he said, “The river would bring fertile soil annually, so the soil was rich forever. We had nine months worth of growing in Somali soil — summer is the three months you cannot grow, it is so hot and the wind is blowing. Here we only have 120 days worth of growing so we are not growing nine months, we are growing three months — it is upside down.”

In spite of the challenges of growing in Maine, the Somalis are able to apply traditional companion planting methods for a bountiful crop. “I’ve noticed that some farmers have the most beautiful way of growing corn,” Lana Cannon Dracup, Somali Bantu Community Association’s farm operations manager, told Down East, “with five feet between each cluster. Then, they interplant things underneath: tomatoes, squash, hardy greens, melons, onions.”

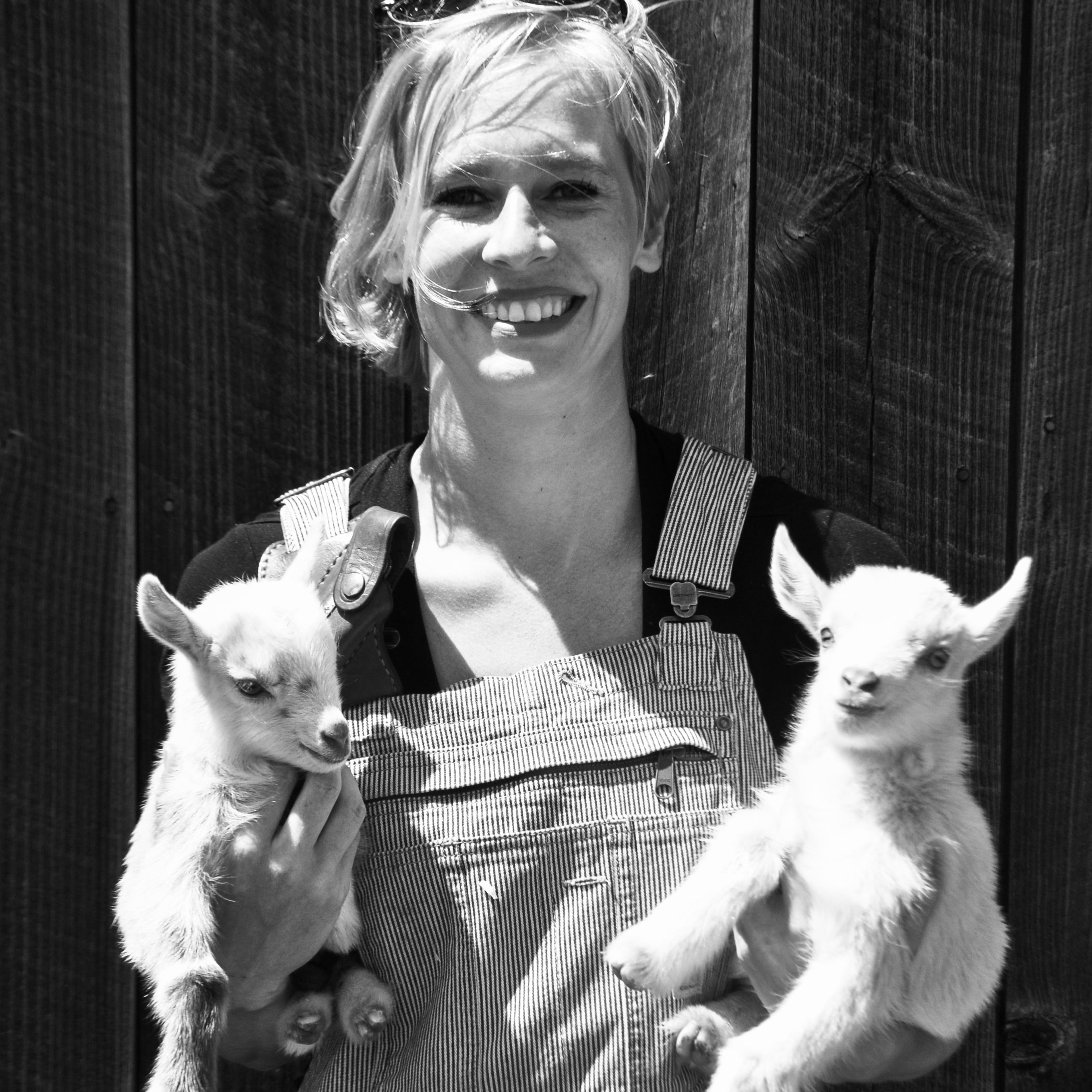

The farm is also home to a small herd of goats and a flock of chickens, which the community uses for meat. They have added a washing station to prepare and package their produce, operate a farm stand during the summer months, and have built three high tunnel green houses since taking over the farm. The neighbors may have been skeptical when they arrived, but the community has thrived in the tiny town.

“The farmers are also setting aside space for cultural events,” notes Kelleher’s Down East piece, “like drumming and dancing, gatherings that can be difficult for a community that largely lives in Lewiston-area apartment housing.”

Visiting in late November, I found Libah focused on planning for the next growing season, while outside in the fields the last ears of corn were being harvested and dried. The farm was preparing for a traditional African market: a gathering of the community where the goats not being kept for breeding the next season are bartered along with other goods.

The farm has grown since the Somali community arrived and now has hoop greenhouses for starting seeds in the spring and drying corn in the fall. Chickens and goats are butchered at a halal slaughtering station and a full washing and processing area has been built for vegetable harvests. Like the hardy flint corn flourishing in their fields, the Somali farmers at Liberation Farms have proven that they can thrive on Maine’s rocky soil.