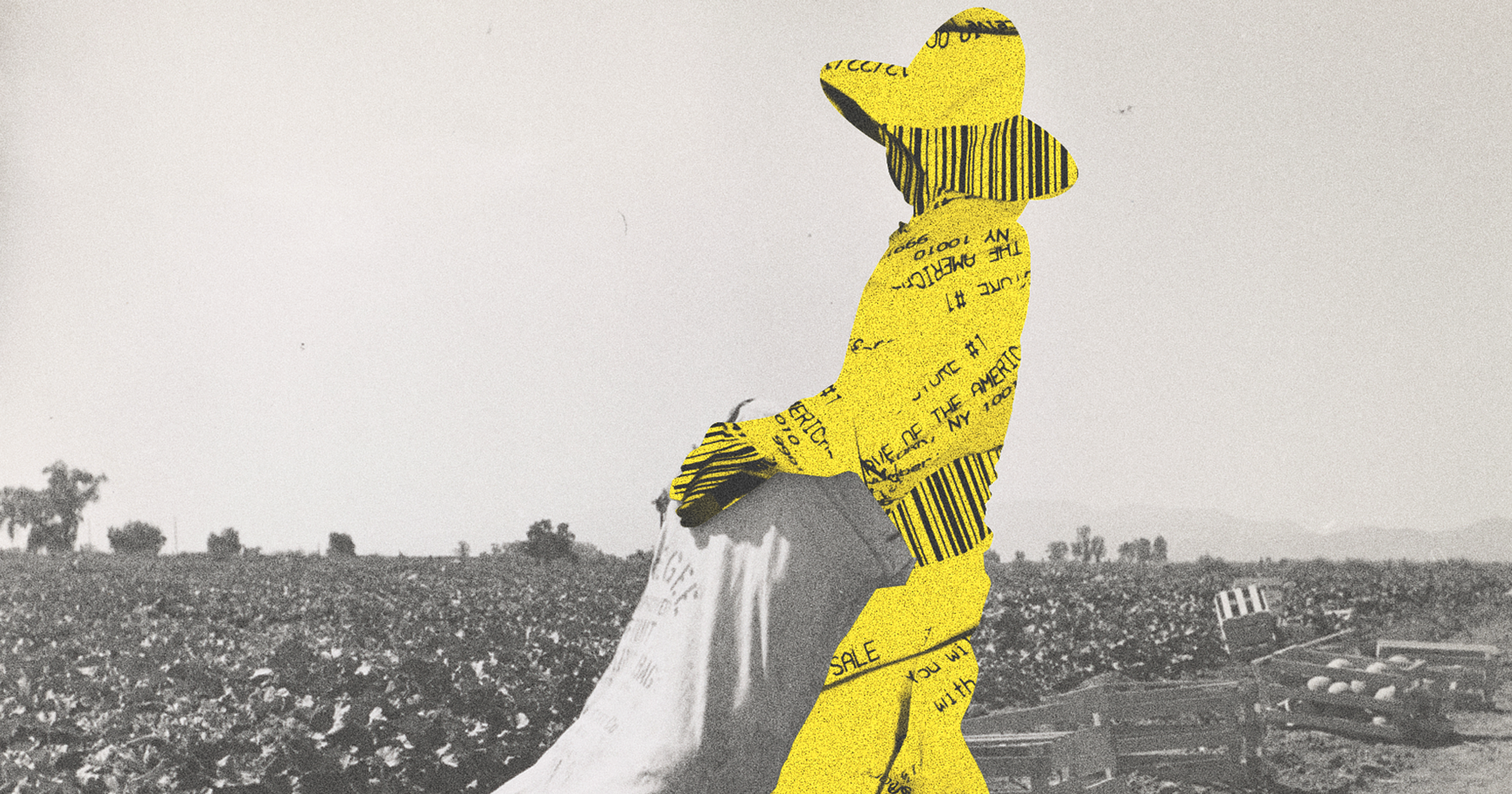

With low incomes and poor access to healthcare, farmworkers suffer an outsized economic impact from a disease many people have never heard of and doctors still misdiagnose.

Years after Valley fever’s symptoms have subsided, former patients and their families still hold vivid memories of the pain and anxiety they endured. In 2017, Gloria Gaytan’s farmworker husband Dionicio likely contracted the fungal infection while tending almond trees in California, while she awaited immigration papers back home in Mexico. She remembers his teary phone calls as he attempted to “be strong” and work through “immense fatigue,” she said, not wanting to lose any wages.

Another worker, José Vasquez, got sick in 2011 and recalls the intense pain caused by his fluid-filled lungs, and his fears about money when he could no longer manage to drive and unload trucks filled with nuts. His wife, Patricia Cruz, came down with Valley fever in 2020 and suffers from it still. But she has no outside help caring for their two young daughters, one of whom has Down syndrome, on days when she struggles to breathe or muster the strength to move.

All three (who spoke to us through an interpreter) live in California’s San Joaquin Valley, where Valley fever is endemic, and where it was discovered in 1894 — hence its full name, San Joaquin Valley fever. Only 40 percent of patients will become symptomatic; they may seek medical care for mild, flu-like symptoms, or for more significant ones like chest pain, dizziness, trouble breathing, and rashes. But in socially and economically vulnerable rural ag worker communities — with low incomes, scant access to healthcare, and little information about services they’re eligible for — contracting Valley fever, said Leslie Wilson, a professor of health policy and economics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), “can devastate families.”

Wilson contributed to a cost-of-illness study that found the most severe cases of Valley fever can cost one Californian $1,023,730 over their lifetime, not including lost wages — “quite a significant burden for the individual,” the researchers wrote. The annual mean wage for farmworkers in California is $34,790. Many are uninsured.

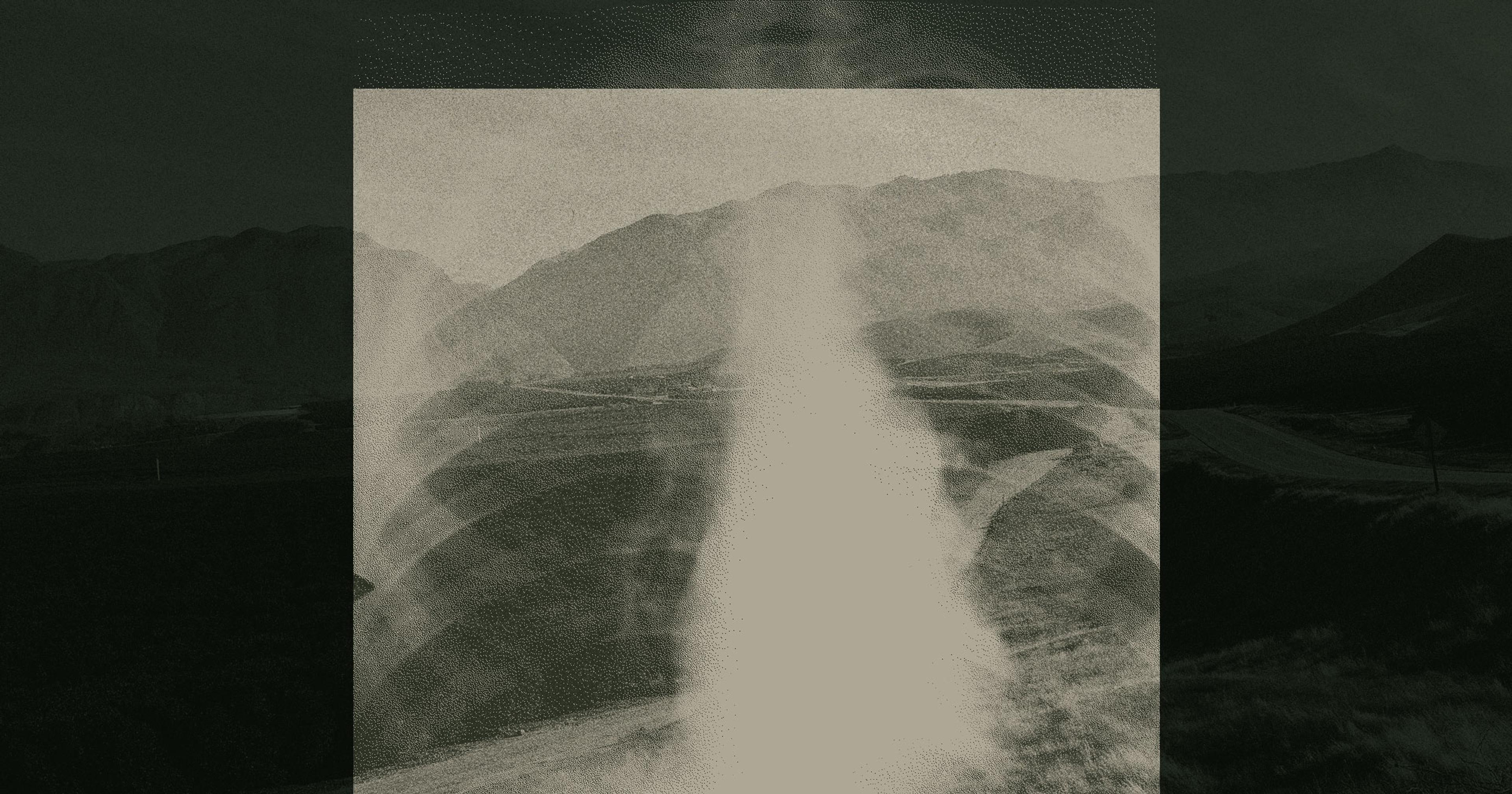

Valley fever is caused by a fungus called Coccidioides, which grows out of decaying rodent bodies in their burrows. It proliferates during the rainy season, and is released into the air when the soil is disturbed, by digging or operating heavy machinery; construction workers are among those most susceptible to contracting the disease. Over the past two decades, it has spread outside its traditional Southwestern boundaries, into Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Colorado, possibly as a result of the warming climate.

The number of cases has also risen precipitously. There were fewer than 2,000 cases in California in 2001; there were 9,004 in 2019. Stats are somewhat higher in Arizona, and together the two states account for the brunt of cases tallied each year (20,003 in 2019), hospitalizations (nearly 2,000), and deaths (200).

Data Source: Centers for Disease Control

Any outdoor worker who inhales spores carried on the region’s copious dust runs a risk of contracting it, as do family members living in poorly insulated housing amid the region’s abundant fruit and nut acreage. Farmworkers working close to the ground, tending root and bulb crops, are significantly more likely than those undertaking tasks like pruning grape leaves to become ill, according to a 2018 study. Study participants reported a median loss of 18.5 workdays — or 10 percent of their annual average.

Said Royce Johnson, medical director of the Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical, “If you’re laid up for three months, that’s an economic catastrophe for families that don’t have a bank account, and we certainly see that frequently.” Kern Medical is what Johnson called a “safety net hospital” whose administrators will attempt to get patients enrolled in an insurance plan or otherwise find funding to treat them, when other hospitals turn them away.

In a small percentage of patients, Valley fever can lead to chronic pneumonia, life-threatening meningitis, multiple hospital stays, and long courses of expensive drugs. Johnson said he’s been treating one such long-term patient since the 1970s.

Vasquez was sick with profuse sweating, pain, and dizziness for three months, during which time he was hospitalized for 22 days; he recuperated at home for another 15 days. When almond season ended, he’d planned to harvest melons but was too sick to work and did not apply for unemployment benefits, even though he was entitled to them, fearing retribution for abandoning his job. Additionally, Vasquez was unaware that under California law, he was eligible for disability benefits. Although his medical care was paid for by Medi-Cal — California’s version of Medicaid that covers families of four with annual incomes under $36,156 — he fell behind on other bills. “My family went through financial hardship,” he said, causing him to sign up for several months working in Alaskan fisheries.

“I had to sleep sitting upward because I felt like I was drowning.”

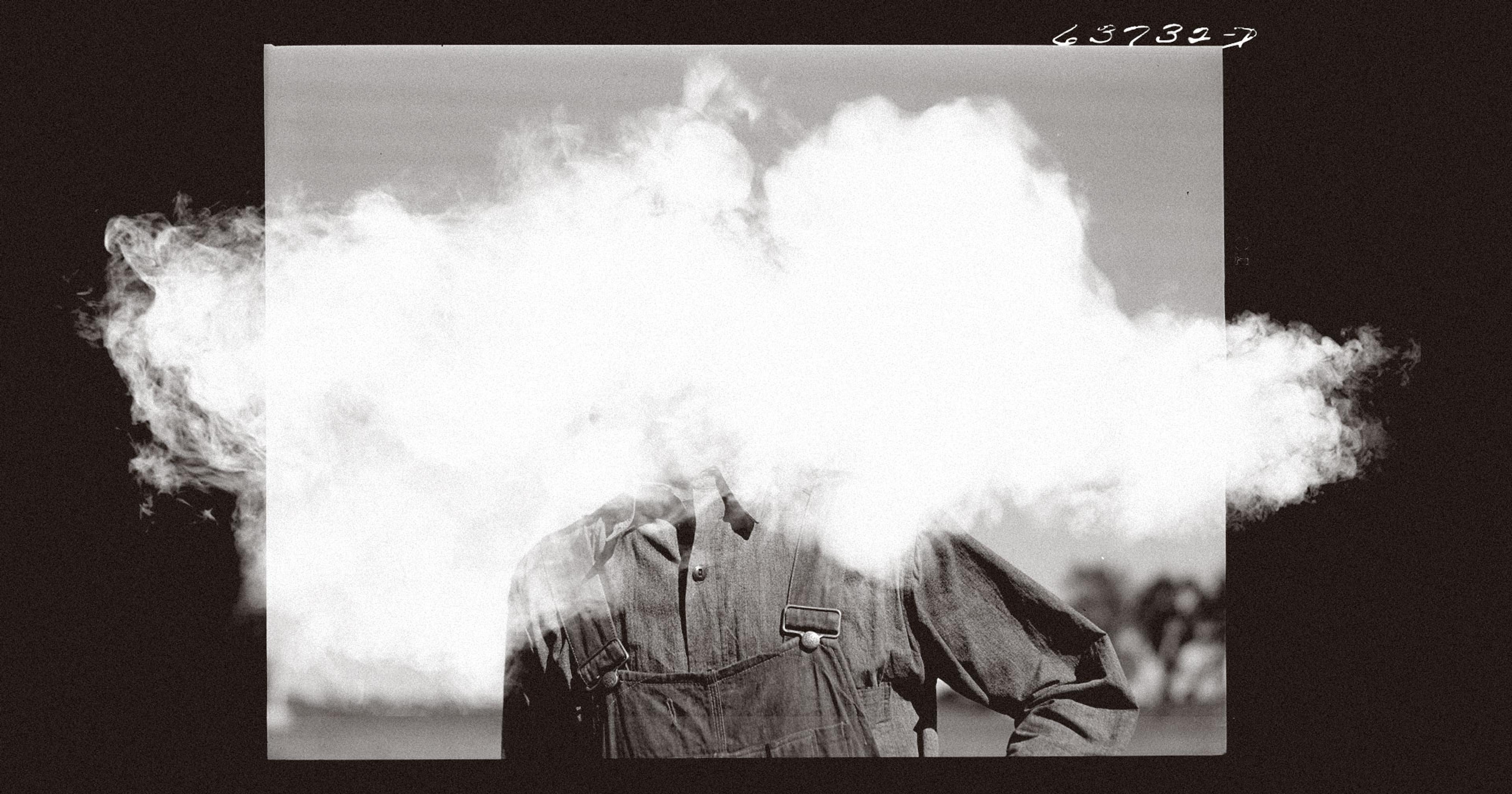

Wearing N95 masks is effective at reducing risk. “But the reality is, it’s 110 degrees out there in the summer and [people] get hot wearing them,” said Katrina Hoyer, who runs a Valley fever lab at the University of California, Merced. She pointed out that workers might also carry dust home on their clothes and infect family members that way. It’s possible this is how Cruz contracted it. There’s not yet a preventative vaccine for humans — although a vaccine for dogs is soon to be released.

Despite the fact that Valley fever has long been known in the Southwest, many patients are initially misdiagnosed; doctors fail to recognize its symptoms and order the proper blood tests for it. False negatives also run high, and false positives are possible, too. Cruz was first hospitalized for bacterial pneumonia and prescribed a round of antibiotics, delaying antifungal treatment for three weeks. In the meantime, “I had to sleep sitting upward because I felt like I was drowning,” she said. Antifungals are expensive — around $1 per pill; Cruz has been taking two pills a day for three years. They also cause side effects like diarrhea, headaches, and dizziness. “Even if they get treatment, it’s not a good situation,” said Paul Brown, a public health professor at UC Merced.

“Patients get anywhere from one to three rounds of antibiotics before they’re properly diagnosed,” Hoyer said, and no one’s sure what effect those might have on recuperation. But for people sick enough to require treatment, a delay in prescribing the correct one puts off recovery and increases medical visits and their attendant costs. On the plus side, contracting Valley fever once probably affords future immunity.

“They’re contract workers and go from place to place. People fall through the cracks.”

To improve healthcare outcomes for farmworkers, Brown sees a need to focus on more testing. “People come through getting treated for pneumonia that’s not clearing up, getting treated again, getting kicked around from place to place until finally they find somebody who tests them for Valley fever,” he said. Additionally, many farmworkers live in medically underserved rural areas where doctors are few and far between. “Some farmworkers get [care from] mobile clinics that come out and do testing, but a lot of them don’t because they’re contract workers and go from place to place. People fall through the cracks,” Brown said.

Improved health insurance coverage might help. In 2024, Medi-Cal will be offered to undocumented farmworkers who fall below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. However, said Hoyer, “Our estimates are that that will raise the coverage rates for farmworkers by about 3 percent — a lot of farmworkers make more than 138 percent. Also, Medi-Cal is not great. [For starters], if you change counties, you have to change medical providers,” as well as find new doctors. She’d like to see farmworkers covered through the state’s insurance marketplace, Covered California, “because that tends to be more portable, and it tends to be for a whole year. The problem is that unless they give subsidies, it’s just too expensive.”

Both the state of California and the National Institutes of Health have increased funding for Valley fever research, which might eventually lead to a vaccine for humans. In the meantime, Wei-Chun Chin, a professor of material science at UC Merced, is working on a new Valley fever test that looks for the fungus rather than a body’s response to it. The test could be used in-clinic and provide results in a half-hour — as opposed to shipping samples out to a lab and awaiting results for two to three weeks.

UC Merced has also begun a program that will train clinicians to recognize locally endemic diseases like Valley fever, and keep them and their knowledge in the community. This year, it admitted its first students to an eight-year program that will grant them a Bachelor of Science degree from UC Merced, then an MD from UCSF’s medical school. “The whole time, they will be very aware of the social determinants of health, and the kinds of healthcare issues that occur in our region,” said Hoyer. “This will be huge.”