As the hottest state grows even hotter, researchers are recruiting Florida farmworkers to test a heat protection wearable. But will it help?

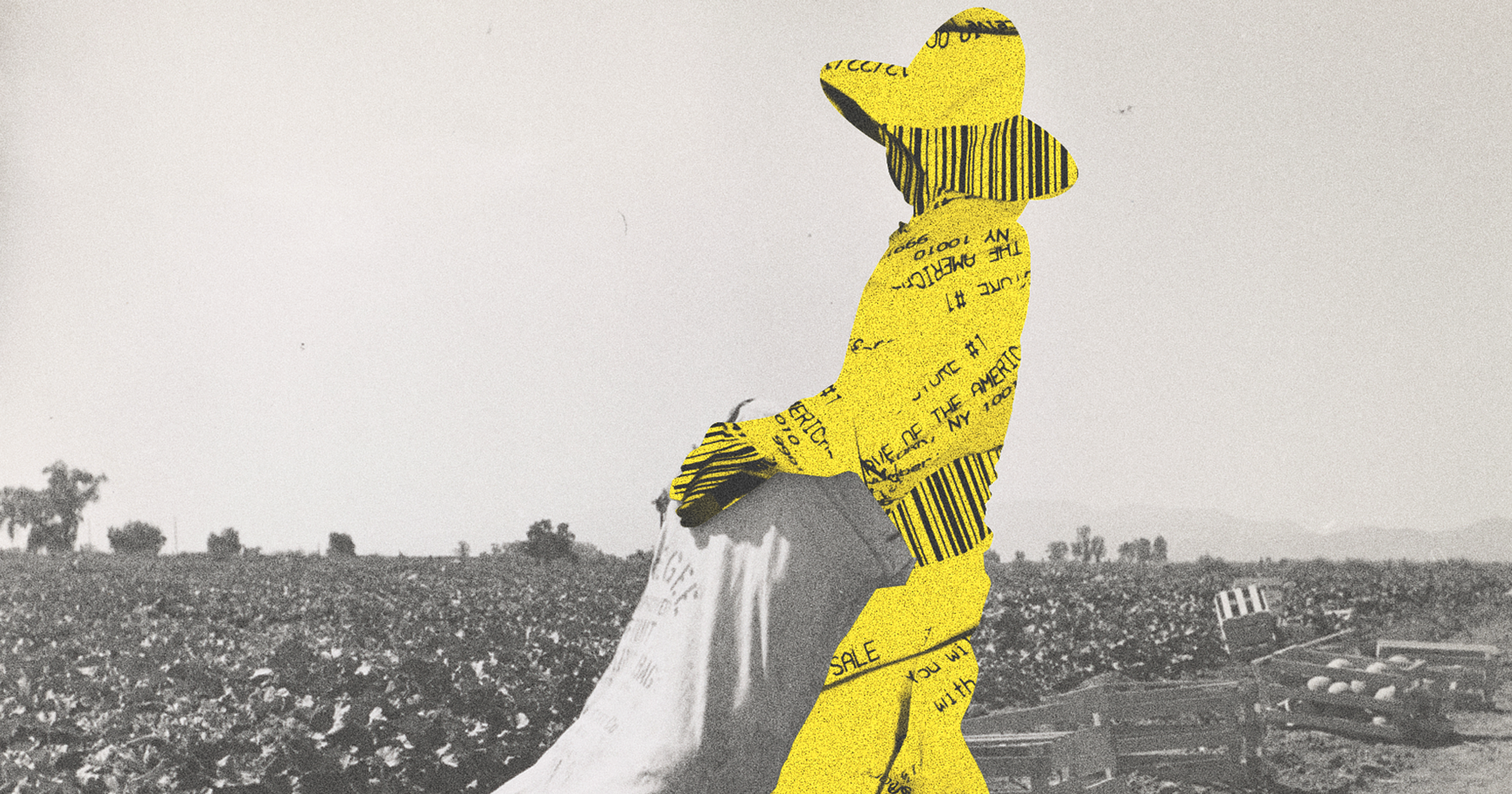

The Sunshine State is the hottest in the nation, bearing down on residents with scorching temperatures and stifling humidity alike. Outdoor workers, including the roughly 150,000 agricultural workers seasonally employed every year in the state, are especially vulnerable.

Summer months on Florida farms are “almost like a sauna,” said Roxana Chicas, a registered nurse and assistant professor at Emory University. The shade cloths protecting crops from sunburn make workers feel even hotter by stopping air flow.

Chicas is working on a solution — a biometric device that warns the wearer they are at risk of heat injury. Researchers at Emory University, Georgia Tech, and the Farmworker Association of Florida are now testing wearable sensors on outdoor workers to better understand heat risks and to develop algorithms that predict the onset of heat-related illness. “The idea is that we will be able to prevent people from having heat-related illness and heat-related deaths,” said Chicas.

Fevers and Kidney Injuries

The research builds on previous findings from the same collaborators, who have worked with landscaping teams, construction crews, and farmworkers. Between the summers of 2015 and 2017, the team tracked the core temperature of 221 agricultural workers using a swallowed, pill-shaped sensor. For three days at a time, while the pill relayed temperature readings every 30 seconds, the participants also provided blood and urine samples before and after work. On average, nearly half the workers exceeded a core temperature of 38ºC (about 100ºF) at some point over a workday. “Farmworkers are working in the field with a fever,” said Chicas. “They may have headaches, muscle aches, nausea.”

Analyzing blood and urine samples, the researchers found that about a third of workers had an acute kidney injury over the course of just one work day. That risk of kidney injury went up 47% for every 5-degree increase in the heat index. “This is not something the workers know that they are developing — they don’t really have any symptoms,” said Chicas. “Once a person has one episode of acute kidney injury, they are at higher risk of chronic kidney disease.”

Florida farmworkers toil under a heat-intensive shade cloth.

·Photo by Roxana Chicas

The risks of heat are worsened by the equipment workers wear to protect against pesticide exposure, added Ernesto Ruiz, a researcher at the Farmworker Association of Florida. Thick clothing with long sleeves, boots, and gloves have the unfortunate side effect of stopping heat from escaping their bodies. And, not only is it difficult to rehydrate in the sweltering conditions, many report feeling pressured to skimp on fluids. “Workers tell us often that they specifically forgo drinking water so that they don’t have to take time off going to the bathroom,” said Ruiz.

Developing a Better Wearable

The earlier research was uncomfortable for workers, who in addition to swallowing sensor pills wore sensor straps across their waists and chests. Engineers at Georgia Tech reworked the sensors, and, after several iterations, developed the less cumbersome device the team is now testing.

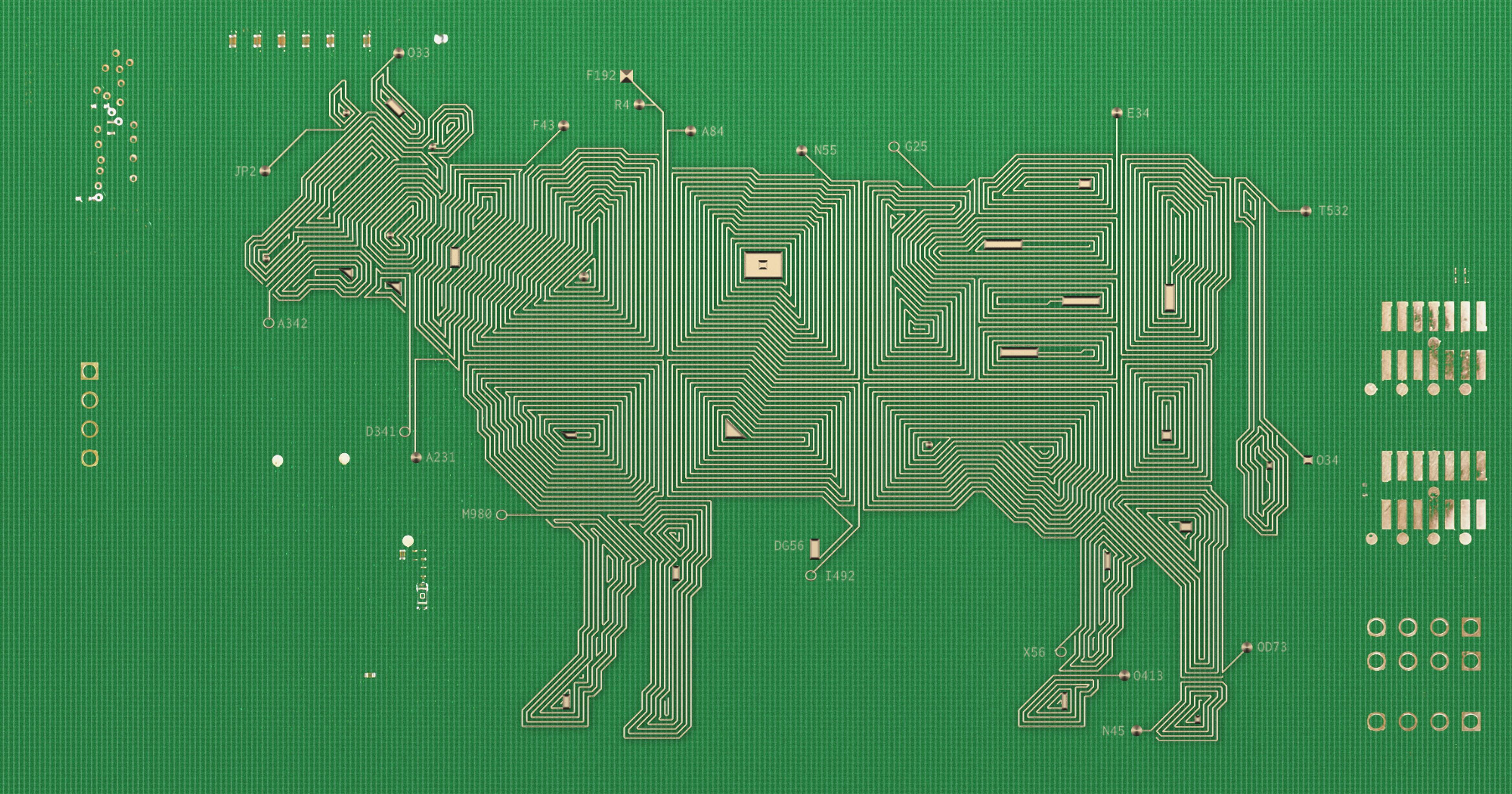

The current wearable is now a single chest patch that sticks like a bandage on the sternum. It tracks the workers’ respiration rate, heart rate, electrocardiogram, physical activity, blood oxygen saturation, skin temperature, and skin hydration — all in a square package about the size of a mini matchbox. The tech is far more accurate than your average smartwatch, using ultra-thin membranes that stay in contact with skin even when the worker is moving, said W. Hong Yeo, an associate professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering at Georgia Tech.

This summer, 168 farmworkers, recruited by the research team, wore the sensor as they labored under the Florida sun, in addition to stopping into a clinic to provide blood and urine samples and respond to a questionnaire about working conditions. The participants also got health test results and nurse advice for markers such as lipid profiles and blood sugar, a valuable service since they are mostly uninsured or under-insured, said Ruiz.

“Workers tell us often that they specifically forgo drinking water so that they don’t have to take time off going to the bathroom.”

The first goal for the summer’s data is to identify biometric thresholds for acute kidney disease, said Yeo. Computer scientists are now training an AI on the data points to develop equations capable of predicting kidney injury.

In the future, the researchers hope the device can ping the wearer’s smartphone when it senses impending illness, notifying them to take a break and hydrate. Connected via Bluetooth, the device could route alerts both to the worker’s phone and even a co-worker’s or manager’s.

Beyond that, the technology could further build on data from worker breaks to refine its alerts, perhaps telling wearers how long to rest or how much water or electrolytes to drink. Data from the breaks on how much a worker’s core temperature cooled or heart rate slowed could provide further information for developing detailed notifications. “That’s gonna be our next step,” said Yeo.

The Limits of Tech

Ruiz hopes the data collected over the course of the collaboration will also influence measures to improve working conditions. Currently, agricultural workers in Florida are not protected by enforceable heat standards at any level of government. Last year, Miami-Dade County officials proposed heat protection standards for outdoor workers. But, after complaints from agricultural and construction interests, Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law a bill that prevents local governments from setting their own heat regulations.

Ruiz said that findings such as those on acute kidney injury can underscore why heat protections are needed. “We need to amplify that to influence policy, to influence public sentiment, and ultimately to enact legislative change around actual worker-centered protections.”

But he is skeptical about the impact of the wearable device itself. Currently, many agricultural workers, often paid by how much they produce rather than hourly, say they feel pressured to push through the heat.

“We need common sense protections, the same sort of things that we offer student athletes.”

To be effective, Ruiz said wearable tech must be part of a larger set of cultural and policy changes. “We need common sense protections, the same sort of things that we offer student athletes,” he said. He adds these protections should include acclimatization periods for new hires, requirements for providing shade and water, and standards for breaks based on temperature and humidity. Recently, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration proposed new rules for heat protection that would enact similar heat safety measures; the proposal is currently in the public comment stage.

“We need tech and policy solutions,” agreed Chicas. She added that the objective information provided by the wearable could help remind someone to slow down at a critical point, avoiding dangerous consequences. She’s looking forward to continuing to refine the device — the next field study will test out health alerts, getting feedback on the alerts from workers.

“I think we can all agree that we don’t want workers dying in the field or having heat-related illness,” she said. “With the implementation of some simple interventions, I think we can protect farmworkers.”