Small farmers and their workers sometimes clash over what comprises fair wages and true educational opportunities.

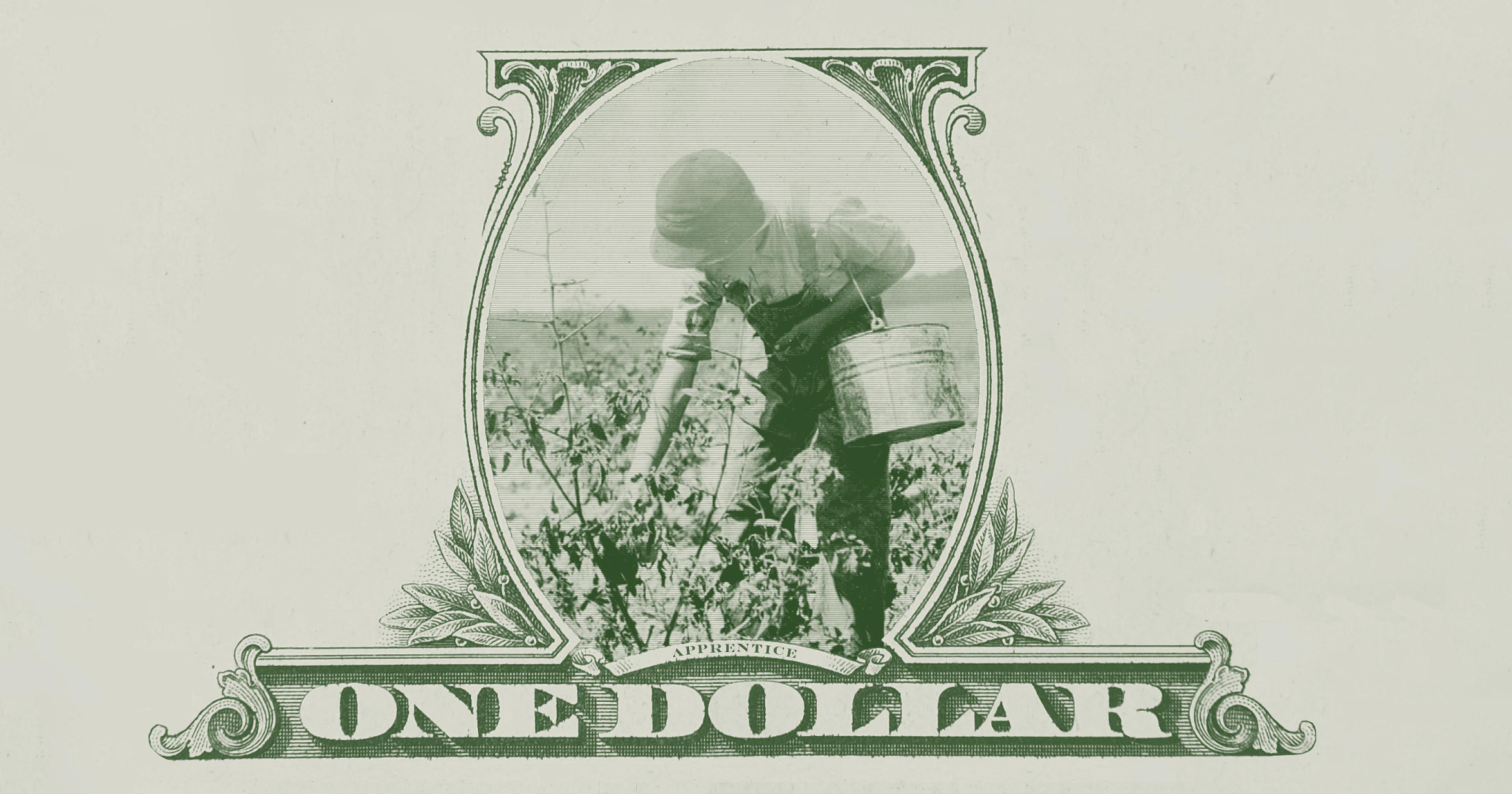

In early March, just in advance of a new planting season, a spirited debate broke out on an agriculture job listserv. At issue was a listing for a farmworker “apprenticeship” that offered free room and board and a stipend that averaged out to somewhere below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. In exchange, trainees would receive hands-on regenerative farming experience. The original poster and supporters maintained that small farms contending with slim margins could not afford to pay more and that the apprenticeship’s educational component tilted the balance to a more-than-fair trade. Critics pointed out the model’s potential for exploitation and Department of Labor (DOL) violations, its economic non-viability for underprivileged workers, and other related problems.

What to pay (or not) a much-needed worker — who happens to be in need of training — has been a contentious topic in ag circles for years. Among farmers young and old, stories abound on the travails of so-called internships and apprenticeships. These terms can comprise what Wendy Chen, a food and agriculture Fellow at the Vermont Law and Graduate School, called “convoluted” distinctions between types of workers. That murkiness is layered on top of (some say unjust) exemptions for small U.S. farms which, under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), don’t have to pay minimum wage to agriculture workers. (Some state laws might override this.)

After finishing a year of courses and training at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Center for Agroecology 12 years ago, Anita Adalja took an apprenticeship on a 20-acre vegetable farm. The position offered a $1,200-a-month stipend and a trailer to share with three other apprentices. “It was not a pleasant experience,” said Adalja, who founded the farmworker advocacy group Not Our Farm in 2019. The farm crew worked at least six days a week from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., using headlamps to harvest in the dark. They weren’t allowed to wear gloves despite bitter cold “because it would damage the greens.“

Adalja got frostbite on several toes and began to develop arthritis. The 100 or so farmworkers in the Not Our Farm network have their own stories, of mold-infested housing, of no bathroom to use during the workday, of working long hours for very little pay. Some of those experiences may constitute labor and/or housing violations under state or local laws, or the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Workers Protection Act. The problem, said Chen, is enforcement.

The FLSA deems a farm small if it used less than 500 “man days” in any quarter of the preceding calendar year; that’s considered the rough equivalent of having seven full-time employees. An “agricultural” job is exempt from minimum wage (small farms) and overtime (farms both small and large), although as a bunch of Vermont farmers found out the hard way, just because a job is on a farm doesn’t mean it’s necessarily exempted.

As the Vermont news outlet Seven Days reported, “Milking cows? Ag. Turning that milk into yogurt or kefir? Nope. Sowing wheat? Ag. Milling flour in the granary? Nope.” Meaning, yogurt-makers and millers are entitled to both minimum wage and time-and-a-half over 40 hours a week. H-2A laborers — 73% of the U.S. farm labor force are migrants — actually must be paid at least as much as U.S. workers, to ensure their hiring doesn’t adversely affect American farmworkers, said Chen.

“We had too little labor, which meant there was too much pressure on our employees and ourselves and we expected way too much for the amount that we were paying people.”

“Intern” and “apprentice” are similarly muddy terms. According to DOL, in most cases an intern is someone who agrees to non-payment in exchange for hands-on training tied to credit in a formal education program. Basically, said Chen, “The employer can’t get any direct immediate benefit from it. You want to train somebody to grow crops? You can do that, but you can’t realistically say in order to learn to do that, [they] have to weed for three days straight because that’s just using deep labor.” It’s a distinction not limited to farming; deviations from this kind of rubric have arisen in other fields as well (notably, in journalism) where use of unpaid interns in exchange for college credit have run afoul of ethics standards.

Meanwhile, “apprentice” isn’t a distinct employment classification unless it relates to an apprenticeship program, such as at UC Santa Cruz, or Wisconsin’s FairShare CSA Coalition, that’s registered with a state or federal labor board. Such a formal program “is usually several years long with a vocational or trade school with credits toward a job and pretty formalized training,” Chen said. No minimum wage or overtime is required here by federal law, but the programs often work out their own standards for fair compensation.

Still, “intern” and “apprentice” might be used interchangeably and have none of this meaning attached to them. Small farmers sometimes maintain that they seek to hire so-called apprentices and interns because they can’t afford skilled workers, and that they don’t have the time, energy, or resources to teach them formally. People at FairShare have heard from farmers who’ve said they didn’t get into farming to be HR managers; that production and not education is what translates into farm stability; and that there’s only so much they can raise prices to meet constantly rising costs — including for labor.

These stressors are familiar to Katrina Becker, who farms 5.5 acres of organic vegetables in Athens, Wisconsin. During Covid, when finding and retaining workers was near impossible, “We had a reckoning as a farm in terms of employment,” she said. “We had too little labor, which meant there was too much pressure on our employees and ourselves and we expected way too much for the amount that we were paying people.” But she also pushed back against the idea that underpaying employees, no matter what you call them, is a necessary practice; she pays at least $15 an hour.

It’s fair to argue that an apprentice requires more energy and resources than a skilled farmworker but, “If you don’t have money to pay someone at baseline minimum wage,” Becker said, “it means there’s other issues with your business.”

It’s fair to argue that an apprentice requires more energy and resources than a skilled farmworker.

FairShare partners with the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development and the Wisconsin Technical College System, the latter of which offers two semesters of courses, between two seasons of on-farm work at organic vegetable farms. This includes learning about farm systems, financial management and marketing, and greenhouse work and pest ID. “People can see, by the time I’m done with this program I will have reached competency in these core skill areas,” said Sarah Janes Ugoretz, FairShare’s apprenticeship manager. Farmer mentors from 22 farms agree to pay at least $7.25 an hour to start, at least $10.50 an hour to finish, including for time spent in the classroom.

It’s worth noting that farmers — including Becker, who felt she had the bandwidth to take on her first apprentice only this year despite working with the program since 2015 — helped design this program from start to finish. In addition to providing extensive resources to help apprentices succeed, as well as inspecting farms for their suitability, Ugoretz also mentors the mentors. She helps address their concerns about how to make time and space for apprentices, and to better help them understand how to succeed.

FairShare is one of only a handful of similar programs across the country, and it’s currently near capacity, with 10 apprentices signed on for this year. But there are other ways to find a decent, less “official” apprenticeship or internship opportunity. Not Our Farm partners with search board Good Food Jobs, which mandates that any posted job pay at least $15 an hour — although, “If you’re not offering housing and your farm is in a really expensive place [for rentals], $15 an hour might not be nearly enough,” said Adalja. She calls the issue of housing “tricky,” since many farmers themselves “aren’t living on the land that they’re farming on and don’t have access to housing.”

In addition to creating several other resources, Adalja has also been working on a toolkit with FairShare that aims to help potential farm apprentices identify red flags during the interview process. Asking questions is important: “Is there a formal structure to it? Is there compensation and are those details laid out? Is there a curriculum and a schedule to guide that training? Are expectations clear? Is there an agreement that is signed? Does that exchange of your labor and that knowledge and compensation feel fair?” said Ugoretz. “Keeping those questions front and center can help people understand and decide, ‘Is this something I want to put myself into?’”