“It would have to be someone smarter than me to lock in a profit because I sure wouldn’t know how to do it right now.”

Twelve months ago, Jonathan Gaskins knew it would be bad.

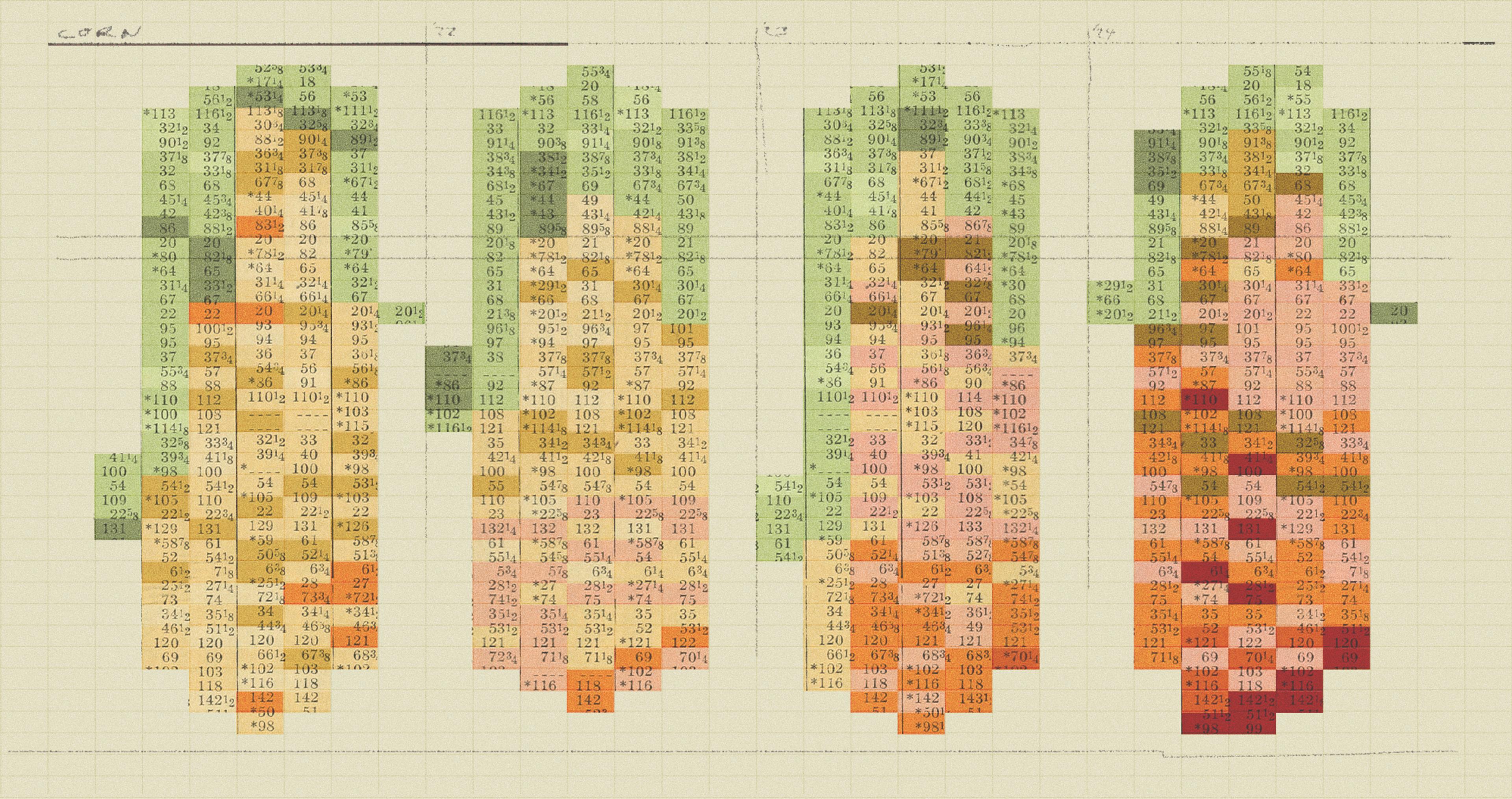

Corn prices, once as high as nine dollars per bushel, were falling well below the USDA’s projected price of $5.91. After banner years in 2021 and 2022, his 5000-acre row crop farm in southern Kentucky was in for a squeeze; he decided to wait it out. Instead of selling, he stored his 2023 corn harvest in hopes of a price rebound. But the 2023 dip was just the start.

“Hindsight is always 20/20,” Gaskins said. “We should have sold everything off the combine.” Since the 2023 harvest, prices have only continued to nosedive.

Gaskins managed to sell most of last year’s crop before prices got so low. But this year’s crop won’t be so lucky. With only 20% sold pre-harvest thanks to a wet spring, 80% of Gaskins’ crop is at the mercy of a commodity market that doesn’t show signs of turning around.

“It would have to be someone smarter than me to lock in a profit because I sure wouldn’t know how to do it right now,” Gaskins said.

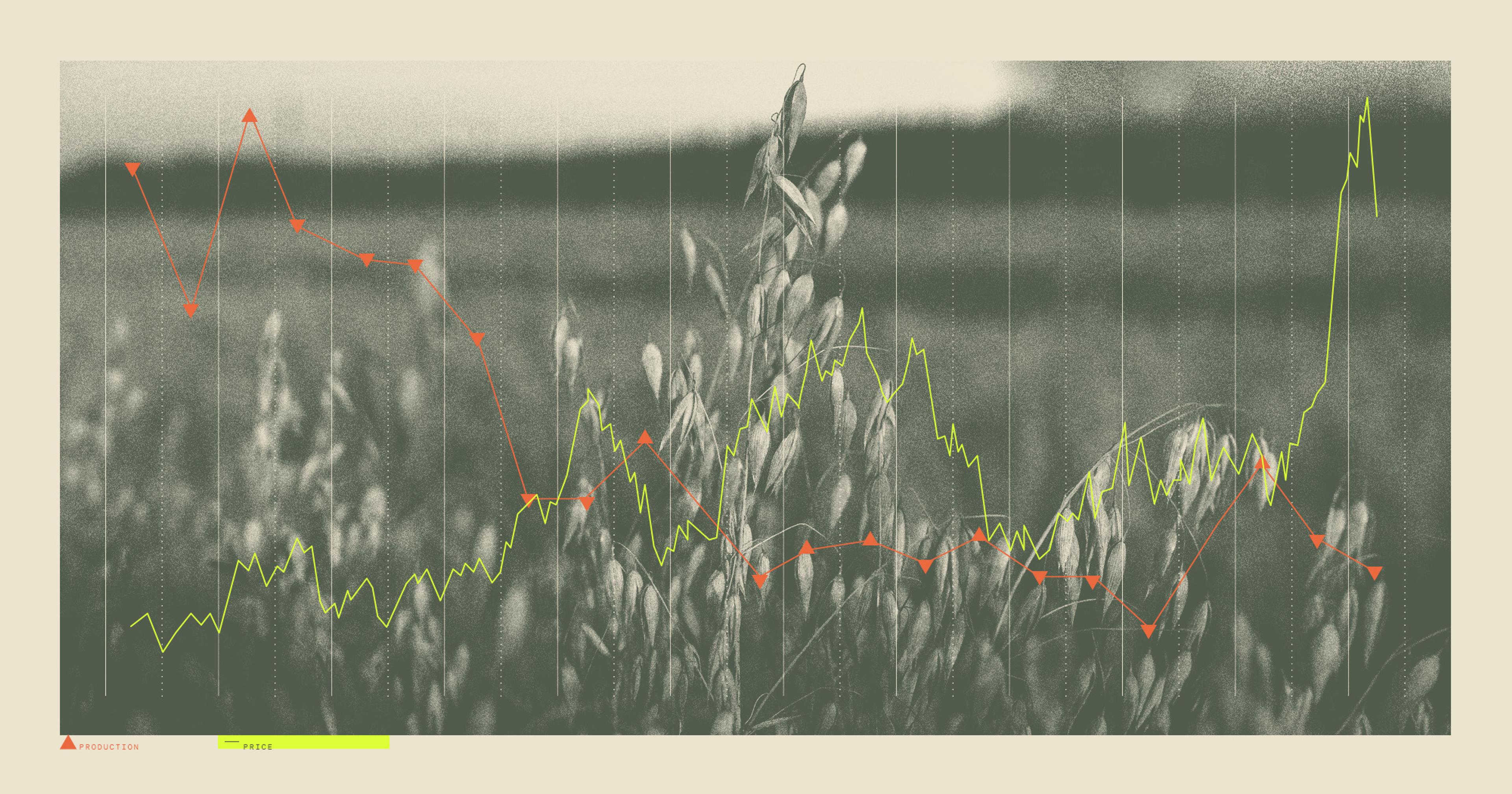

There are countless farmer stories like Gaskins’. After all-time high prices in 2022, U.S. ag markets have taken a downturn and no one is sure how long they will last. 2024 saw corn and soybeans on razor-thin margins, unlikely to make enough to pay back the loans taken out to grow them. Ag lenders are now preparing for repayment problems and loan restructuring as farmer cash-flow takes a dip. And experts say federal dollars won’t offer much relief. To make it through, good business — like built-up cash, outside income, and lender relations — will be more important than good farming.

“The ag industry, like a lot of industries, goes through cycles,” said Nathaniel Watts, vice president of credit agriculture underwriting at Farm Credit Mid America. Downturns are expected, he said, but they also demand quick operational changes. “When market conditions are down, producers must quickly adapt and manage their costs,” he said.

Watts said Farm Credit has already asked its financial officers to help vulnerable customers find their breakeven and proactively reduce expenses to meet it.

The price drops are so severe that breakeven may be the best some farmers can hope for. For example, once you account for land rental costs, Illinois farmers will be losing money this year, said Brittney Goodrich, an agriculture economist who studies risk at the University of Illinois. And Illinois is typically one of the more profitable corn and soybean states in the U.S., since it has fewer irrigation costs. “I would say other corn and soybean-producing states are going to be hurting even worse,” Goodrich said.

“We are sitting on a pile of corn.”

The falling crop returns are largely a product of inflation and surplus. The cost to produce corn and soybeans increased dramatically during Covid’s peak, according to Michael Langemeier, associate director of the Center for Commercial Agriculture at Purdue University. Growing a bushel of corn that once cost four dollars now costs five or more, he said. That wasn’t a problem when prices were high, but now “we are sitting on a pile of corn,” Langemeier said.

Gaskins isn’t the only one that held onto last year’s harvest in hopes of better prices. The USDA estimates that in June 2024, there were still 3 billion bushels of corn sitting on farms unsold — up 37% from 2023 — and another 1.97 billion bushels in commercial storage. Meanwhile on-farm soybean stocks were up 44% from a year ago. It’s basic supply and demand; the surplus is already driving down prices while the Midwest — which dominates row crop production — is expecting a bumper crop.

That means the federal farm safety net won’t offer much relief, said Gary Schnitkey, agriculture economist at the University of Illinois. Despite extreme weather that delayed planting and overheated crops during the growing season, harvest for most row crop farmers was too good for crop insurance to kick in. And because 2024 corn and soybean subsidies are based on 2023 harvest prices, which weren’t all that low, farmers will see little if any federal dollars. The proposed FARM Act would offer crop farmers rescue payments, but Schnitkey said it won’t be voted on until after the election.

Daniel Sumner, ag economist at University of California, Davis, said that talk of an ag downturn is “a very Midwest perspective.” Not all of agriculture is in trouble. Most California specialty crop markets are doing well. Milk prices are better. And cattle prices are way up. Plus, anyone feeding livestock stands to benefit from the low commodity prices, Sumner said.

Still, corn and soybeans are important, he said. Corn, alone, generated more farm income than cattle in 2022. And when the commodities take a hit, they tend to take other ag sectors — like equipment — down with them.

“That’s what happened with the layoffs at John Deere,” Langemeier said. Seeing prices fall, farmers have to cut costs and new equipment is first to go.

Farmers can only cut costs so far — inputs like seed, pesticides, and fertilizer have no workaround.

But farmers can only cut costs so far — inputs like seed, pesticides, and fertilizer have no workaround. And the price of these inputs has remained high despite falling crop prices. A survey by the Kansas City Federal Reserve reported that many farmers in the region are approaching their credit line max earlier than usual, due to rising production costs.

“Most of these operations take out operating loans every year” to cover input costs, Goodrich said. Facing high costs and low returns, farmers that don’t have cash on hand “may not be able to pay back those operating loans,” she said.

According to Watts, many farmers — if they’re proactive — will be able to weather this downturn by tightening their financials and using cash reserves from better years. But some will undoubtedly need additional financial support. Anyone who took on lots of debt for land, equipment, or other fixed costs will be under more financial stress, because “those payments are required no matter if corn brings $5 a bushel or $3,” he said. Young farmers, because of their high debt load, low cash reserves, and need to grow, are especially vulnerable during a downturn, according to the University of Illinois farmdoc daily.

These financial hurdles are being negotiated in real-time. If you’re a Midwest corn or soybean farmer, “you know your lender and interact with them on a weekly if not daily basis,” Goodrich said.

And lenders have strategies to take some of the immediate pressure off. When the time comes, Watts said, FCMA is prepared to offer loan services like additional financing or debt restructuring to help farmers free up some cash and keep going.

Still, that financial lifeline is not one you want to have to take, Gaskins said. He’s been there. In 2009, he couldn’t repay the operating loan for his 300-head dairy. The lender worked with him, but he spent five years paying off that loan.

At least this year, Gaskins expects most farmers will be able to pay back operational loans — even if they don’t turn a profit — because they have cash on hand from the last couple of years of high prices.

“We hope — and hope is never a good marketing plan —that something turns around.”

The Kansas Federal Reserve confirmed as much, reporting that even with sharp decreases in farm income and capital spending, ag credit stress remains limited. In a survey, ag lenders reported some emerging signs of financial stress, like modest deterioration in farm finances, gradual decline in farm loan repayment rates, and a slight rise in farm loan repayment problems.

Most row-crop farmers are still working with a fairly strong balance sheet, Langemeier said. The U.S. farm debt-to-asset ratio is low, land values are strong, and farmers built up liquidity in 2021 and 2022. “We can withstand one or two years of low margins, but it will bleed that liquidity down,” he said.

In 2016, Gaskins‘ operation launched a fertilizer sales business. Today, the business does more than 10 million in annual sales, but this will be its first time facing a downcycle. And it’s Gaskins’ first time weathering a downturn with an accounts receivable department.

The debt load, his customers’ ability to pay their bills, “that worries me more than my own operation,” he said. “I know where I’m at on my operation but other people I don’t know as much about.”

For now, the fertilizer business and Gaskins’ 300-head dairy help offset the low commodity prices. But a few years at this rate and Gaskins says it will get a lot tougher.

While no one knows how long a downturn will last, it’s rarely just one year, according to Watts. In past cycles, periods of high prices are traditionally followed by multiple years of low prices.

Barring a devastated harvest or international event, Gaskins doesn’t expect to see things change soon. “I think we are in for at least two years, maybe three of losing money,” he said. In the meantime “we hope — and hope is never a good marketing plan — that something turns around.”