Deep in West Virginia coal country, a lavender farm attempts to strike a balance between profit, cultivation, and remediation.

When Charles Bowman worked seven miles underground, he spent days in complete darkness, no light but for what comes out of a lamp on the forehead. One day, a piece of metal 15 feet long fell on him from behind and drove him headfirst into the ground. Left with five blown-out discs, nerve damage, and a spinal cord stimulator, he found himself unable to continue work as a coal miner.

Today, in the middle of June, he is bathed in light. He is sweating, in fact; the flattened-out hollow of an old surface mine on a West Virginia mountain is blazing hot. The mercury reads about 85, but with dense humidity pouring off the surrounding forests and unrelenting sun, it feels more like 400 degrees. He and a team of roughly a dozen other farmworkers are crouched, clipping single stalks of lavender from clusters in the rocky ground. This is the Ashford Farm, formerly known as the Appalachian Botanicals farm, which has been cultivating lavender for five years on the same mountain where Bowman spent 14 years underground.

“The reason I took this job, is with all the coal mines shutting down, I wanted to still be involved with West Virginia. I’m a West Virginia boy, I love the mountains. And this” — he gestured toward the field around us — “wouldn’t be nothing, it’d still just be a flat bottom.”

The coal-rich region of Appalachia is pockmarked with old mine lands that lie spent from their former use. Coal mining, regardless of its potential economic merits, pretty much obliterates the ecosystems it touches. When you blow the top off a mountain to chisel out the coal within, you can never build it back. You can, however, make efforts to heal what’s left of the ecosystem, which is mandated by the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977.

And once that ecosystem is healed, must it serve some economic purpose? It’s a question without an easy answer — these are millions of acres of polluted and degraded rock in remote, sparsely populated areas. And the communities that formed around them have relied primarily on pulling coal from that rock to make a living and support their families. How can the land support them now?

In West Virginia, the answer to that question has largely revolved around timber — more extraction — and tourism. Farming remains a fairly fringe proposition.

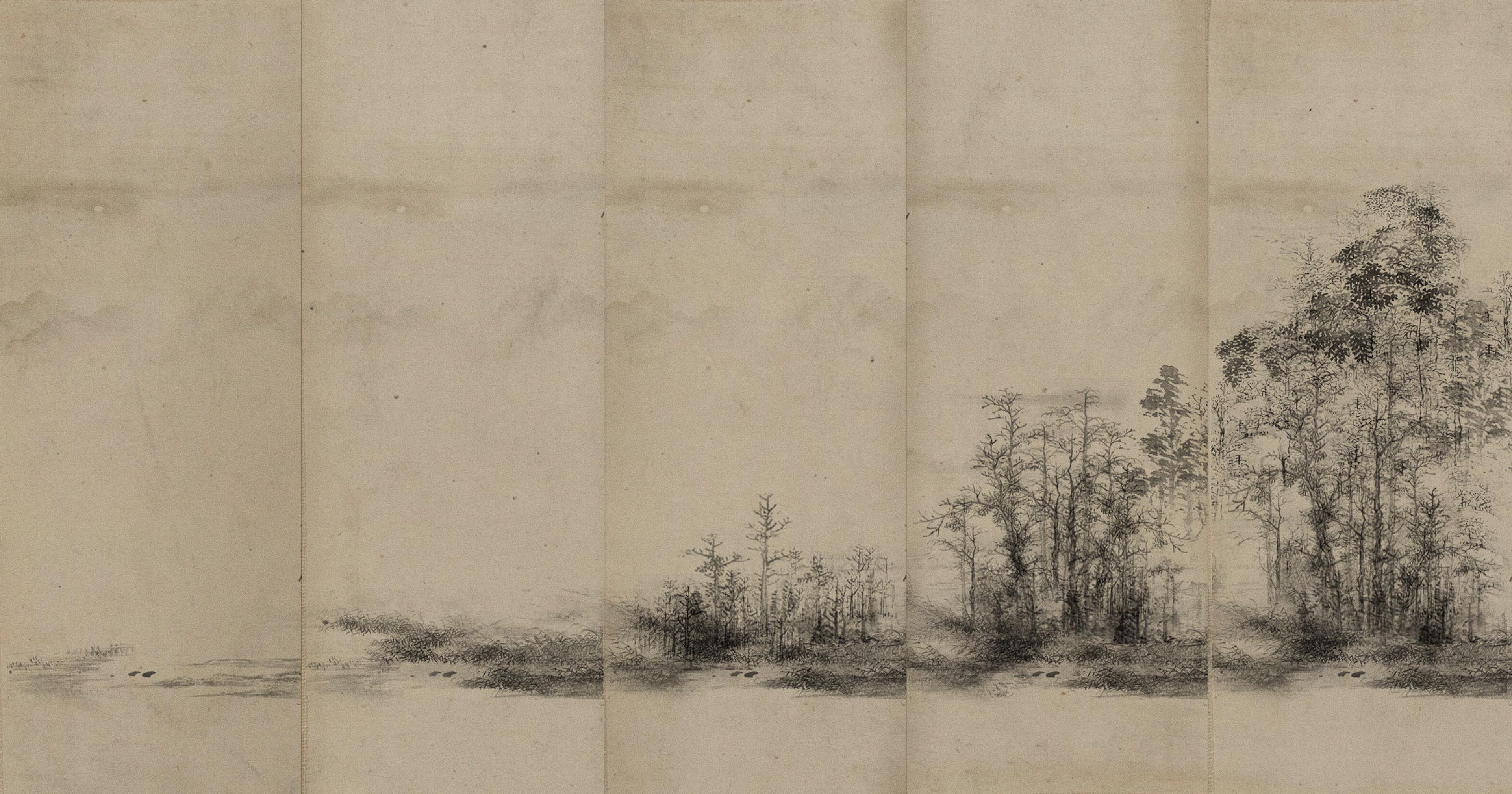

An aerial view of one of the fields referred to as “the Bowl” by the workers at the Appalachian Botanicals farm.

A farm’s success is inherently dependent on striking a balance between exploiting the land and caring for it. You’re removing a plot of land from its natural state and coaxing it into an artificial purpose: the cultivation of crops for human use and consumption. But if you push the land too hard, and do not allow it to rest or restore, it will produce less and less.

It’s an immense challenge to run a farm even in the most forgiving of soils, to say nothing of the ruins of a mine. What does it take to sustain it?

_______________

Here’s how reclamation works, in simplified terms: To be able to mine on a given site, a coal company is legally required to take out a bond that gets released once they’ve restored that site to a reasonable degree of ecological health. (Kind of like a security deposit.) The release of that bond occurs in stages, upon meeting various requirements: keeping pollution out of waterways, fortifying against landslides, and planting new forests and vegetation over rocky remnants.

The system has yielded varying degrees of success. In the worst case scenario — if coal companies go bankrupt, or pretend to have ongoing mining activity on sites that are actually abandoned — they can evade responsibility for remediation. In the case of bankruptcy, that means that states are left to clean up the mess. In the case of evasion, it means that the communities living alongside and downstream of those mines have to endure pollution for which no one will claim responsibility.

And even when former mine sites are successfully reforested, the ecosystems are not necessarily healed. When the earth is still bare and raw immediately after mining, it’s most vulnerable to invasive species like the autumn olive. When those take root, they’re very difficult to eradicate, and can overcome the native organisms that sustain the ecosystem.

Dakota Graley, 18, harvests lavender from one of the thousands of plants in the main field at Appalachian Botanicals lavender farm.

But the prospect of putting a farm on a former coal site is highly ambitious and pretty rare — at least in the mountainous Central Appalachian Coal Basin, which stretches across the state of West Virginia into eastern Kentucky and Tennessee. This is not a region that is known for quality farmland to begin with. It’s all steep slopes and hollers, shallow layers of soil over rock formations. W. Lee Daniels, professor emeritus of plant and environmental sciences at Virginia Tech, estimates that less than 10 percent of former mine lands in this region go to agricultural use, in plots just a few acres in size.

Lavender, however, is a good match for mined terrain because it’s a relatively low-maintenance crop that thrives in dry, rocky soils. It also provides a very romantic, media-friendly narrative: from dirty coal to aromatic lavender, ruined land to fields of blooms. In 2017, the Green Mining initiative earned some optimistic coverage for its vision to transform a strip mine in Kanawha County into a lavender farm. It brought in would-be farmers from across the country to learn how to grow the crop, with the goal of eventually making them cooperative owners. But it quickly ran out of funding, and the lavender crops that survived the first planting were tended by volunteers.

Jocelyn Sheppard, who worked as a consultant for nonprofits at the time, had helped secure the grant for the Green Mining Project. A similar project could serve the community by providing reliable employment, she believed, as a for-profit business. With the support of a private investor, she signed an agricultural lease with the property owners of the Raven Crest mining complex in Ashford, West Virginia, and started growing lavender on 38 acres of partially remediated surface mine in 2019.

Dakota Graley, right, and Kaleb Hanshaw, director of reclamation & remediation for the Center for Coalfield Development, work to harvest lavender in the main field.

“It’s been reclaimed so technically it’s usable for something,” she said. “We’re this 38-acre piece of a 2000-acre coal mine site, and a chunk of it is still active. No one’s gonna build houses up there, no one’s gonna put in a store, a hotel, you couldn’t have people camping or hunting. There isn’t going to be anything to do with it other than grow something on it.”

But growing something, especially on reclaimed mine land, is a significant challenge. Sheppard had no agricultural background, and running the farm was a learning process. Other commercial lavender farms have been able to capitalize on picturesque, delicious-smelling land by hosting weddings, tours, and other Instagrammable events — the still-active mine all but ruled out these prospects. And finding enough lavender buyers to sustain the farm proved challenging, so Appalachian Botanicals developed its own product arm to be able to process and sell the crop in the form of essential oils, mists, and lotions. The company opened a manufacturing facility and store in the town of Foster, a few miles southeast of Ashford.

About a year ago, Sheppard came to the conclusion that operating the farm was too costly, and started to look for partners. In April, she announced that the West Virginia-based nonprofit Center for Coalfield Development would take over management of the farm, and it would be transferred to a new nonprofit entity “so we’d be eligible for grants and other types of support to sustain the farm in future years.”

The beehives at the Ashford Farm serve not only to pollinate the plants, but the honey is harvested as well.

Under the Biden-Harris administration, there’s more and more government money to clean up the mess left behind by fossil fuel companies. In 2022, the Center for Coalfield Development and West Virginia University won $63 million in funding from the Build Back Better framework to “take [West Virginia’s] former mine lands and turn them into assets,” in the words of a press release announcing the grant.

Kaleb Hanshaw, Center for Coalfield Development’s director of reclamation and remediation, took over the farm in May. Hanshaw, a former youth pastor, homesteads on his property outside of Huntingdon, West Virginia, and is certified in permaculture design. He drops reference to the teachings of Alan Savory into conversation, talks fervently about the balance of bacteria and fungi in the soil of a healthy ecosystem, and earnestly cites The Lion King’s “Circle of Life” as an agricultural philosophy.

Most industrial reclamation efforts are insufficient to actually restore a mine site to ecological robustness — they’re more about removing contamination than boosting health. Nor is a single-crop farm an effective method of ecosystem restoration, Hanshaw explained in a narrow shady grove next to rows of lavender in the softly sloping “bowl,” cradled on each side by forested mountains.

Charles Bowman, Nate Withrow, and Brian Bentley take a break from harvesting lavender near a road grader owned by the nearby mining company.

“The soil’s not healthy yet,” he said. “We’re impressed with the way Appalachian Botanicals was utilizing land that wasn’t used before with lavender, and it gives us the responsibility to go forward with reclaiming this site and move away from a monoculture to a diverse ecosystem.”

The eventual goal is to bring in complementary species of plants and livestock: plant fruit trees, strawberries, and melons; bring in herds of sheep to graze weeds and encourage pasture grasses around the lavender; bookend the lavender rows with water-hungry plants to draw excess rain away from the crops. But there’s a lot to do in the meantime, to improve conditions on the farm itself. Center for Coalfield Development’s resources, thanks to significant government grants, have allowed the farmworkers to get pay raises and health insurance, to buy safety equipment and trucks, and shelter from the blistering summer heat.

But there’s a delicate balance of factors that are required for the longevity of the Ashford Farm. The corporation that owns the land could decide to sell, which could jeopardize the lease. The farm has to maintain a positive relationship with the operating mine nearby. And a lot of the current funding opportunities could shift with a change in political administration.

"The Bowl" sets higher than most of the other fields and half of it is surrounded by a ridge to the south.

“From what I know, and I’ve seen, a lot of Appalachian land has been taken for energy for the country,” said Tommy Cook, a 25-year-old farmworker who’s lived in Boone County his whole life. “Once you’ve grown up with those mountains so long, and you’ve been all over them and they’re just gone, it breaks your heart to a certain degree to know I’ll never see that mountain again. But I’d rather see trees and foliage, and that part of the mountain won’t be just barren dirt anymore.”

While the farmworkers on the Ashford Farm make less than half of what they would in mining, they try to find value in the act of restoring what’s been lost. The market does not reward caring for earth; it rewards taking from it. It is also challenging work, contending with the whims of wild flora and fauna and the shifting demands of a changing climate. But at the end of a long day, Charles Bowman observed, when the wind hits at the right angle, the rows of rippling lavender look kind of like the ocean.