Whether from grow-your-own kits or commercial producers, non-native fungus is among us.

Golden oyster mushrooms are the labradoodle, nay, the goldendoodle, of mushrooms. They are popular, pretty to look at, easy to raise, and highly adaptable.

That last attribute, it turns out, can be a problem.

Some months back, a Subreddit thread contained a warning about oyster mushroom grow-your-own kits. Beware, they can take over your couch, your rugs, or really anywhere the spores migrate to and settle in. Some experts have said this dramatic case of “good mushrooms gone bad” may be apocryphal, or at least exaggerated, and that grow kits pose little danger to your home.

But that doesn’t mean there is no cause for alarm. Non-native invasive golden oyster mushrooms are now in the wild. A lot of them.

There isn’t consensus about whether they came from kit mushrooms abandoned in the backyard or from spores creeping out from commercial growers. Either way they are proliferating, with the potential to crowd out indigenous mushrooms, other plants, and even animal habitat.

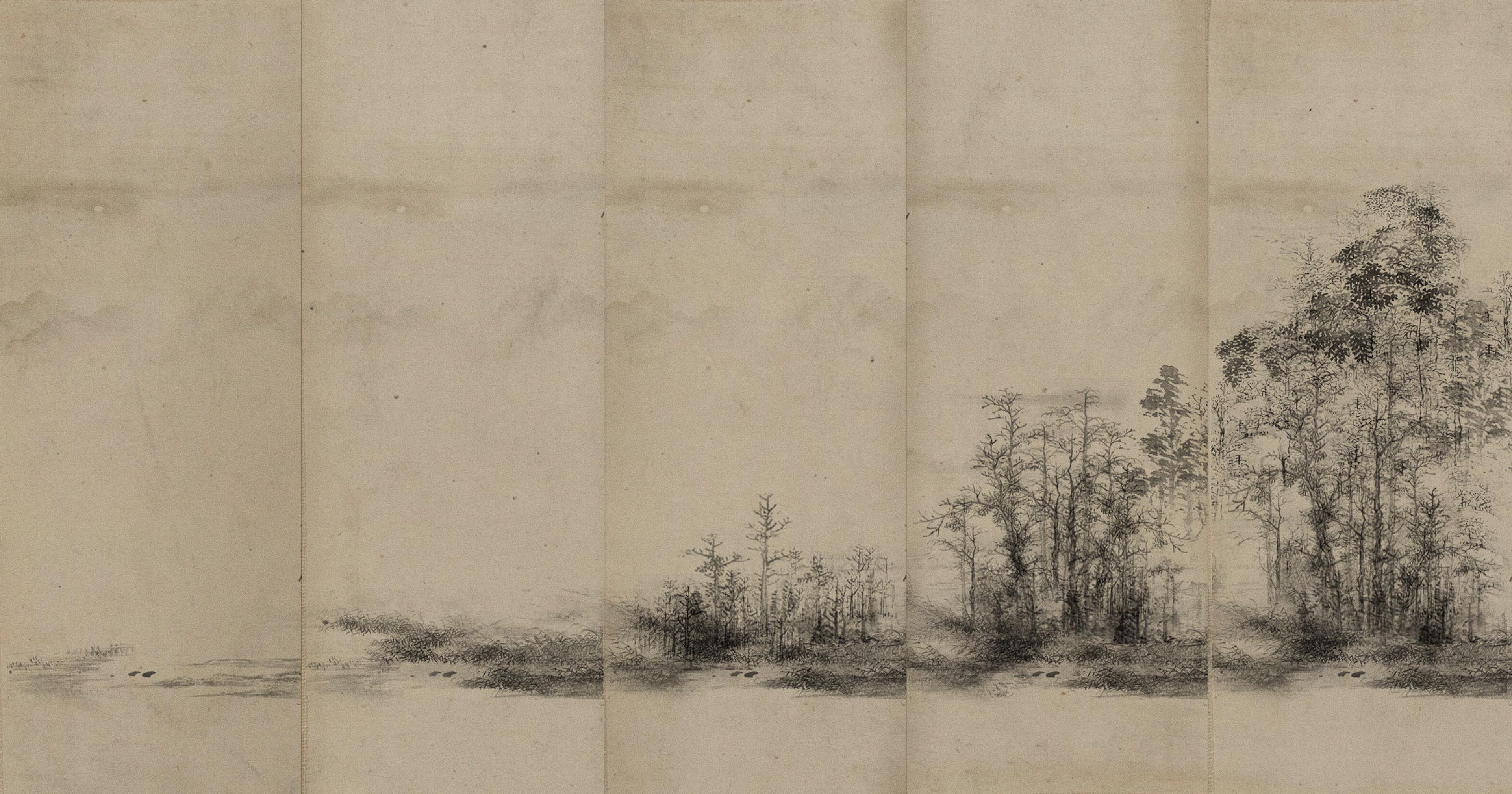

“Fungi have been overlooked in conservation and biodiversity frameworks,” said Anne Pringle, a mycologist in the botany department at University of Wisconsin-Madison. “People have a very strong sense that there is such a thing as an invasive plant — that concept is not controversial. But as humans, we don’t have an equivalent sense that fungi can also have a biogeography, and because we don’t have that sense of the biodiversity of fungi, we have that perception that moving them around is not harmful.”

With the proliferation of mushroom and mycelium uses far beyond food — as packing and building materials, as clothing fibers and leather alternatives, as biodegradable coffins and as soil cleaners — it’s easy to imagine globetrotting non-native species.

Andi Reisdorf’s master’s thesis was likely the first document to sound the alarm in 2018. Reisdorf (née Bruce) published a study examining the spread of non-native golden oyster mushrooms (also called “GOM,” yellow oyster mushrooms, or Pleurotus citrinopileatus), which she said represents the first known case of a cultivated mushroom spreading quickly and widely outside of its native range. She used citizen science data to track its growth across at least nine states.

“One of the reasons we’re lucky here is that it’s such a charismatic mushroom, so people are noticing it and recognizing it as an oyster. So that helps a lot,” she said. “Its invaded range is continuing to expand and its density is increasing. From my perspective, for something to spread so aggressively and so fast that native decomposers are being outcompeted and displaced, it’s alarming. Two fungi can’t occupy the same space.”

“For something to spread so aggressively and so fast that native decomposers are being outcompeted and displaced, it’s alarming.”

Now found throughout the Midwest and Northeast and into Canada, golden oysters are native to the subtropical hardwood forests of eastern Russia, northern China, and Japan.

The big threat is to biodiversity, Reisdorf said.

“Strong biodiversity is really important to ecosystem function. We don’t have measured evidence about specific impacts, but it’s not a stretch to infer that biodiversity is being threatened here,” she said. “And climate change adds an additional threat.”

Many experts have posited that with shifts in temperature and other conditions, fungi may evolve, introducing new fungal diseases.

Two of the central people doing work on invasive golden oyster mushrooms are Michelle Jusino, a research biologist with the USDA Forest Service, and Aishwarya Veerabahu, a graduate student in Pringle’s lab.

Veerabahu cautions that their data is only preliminary and nothing has been published yet, but that the spread of GOM is heavy in the Midwest and in the Northeast.

“In the Midwest you’re very likely to see golden oyster mushrooms in the woods. People are walking out with garbage bags full.”

“In the Midwest you’re very likely to see golden oyster mushrooms in the woods. People are walking out with garbage bags full — whether the intention is to eat them or just to get them out of the woods,” she said. (She cautions amateur mushroom foragers to never eat wild mushrooms unless they have received training.)

Ah, but maybe this is a problem Americans could, with enough training, eat their way out of? Nope. Veerabahu describes it as a “genie-out-of-the-bottle situation.”

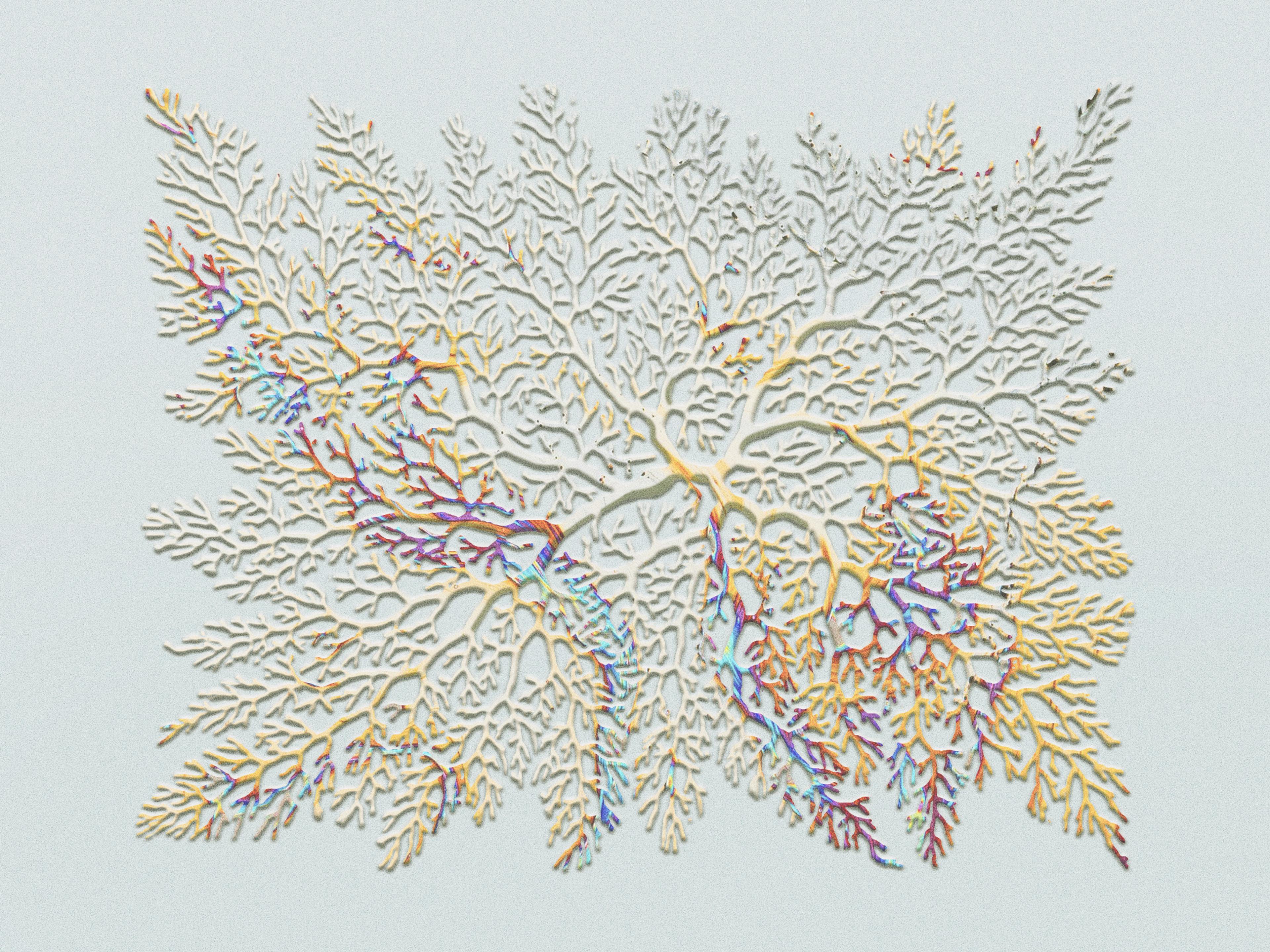

“The way that mushrooms grow, that is not really an option,” she said. Mycelial thread grows through soil, wood chips or other substrate, she said. When it’s ready to produce a fruiting body, it forms a mushroom above ground. That can be plucked or removed, but the rest remains underground.

“There’s practically no way to get rid of it,” she said.

Jusino said there have been other invasive fungi, such as the death cap in California, which likely arrived by hitchhiking on plant imports. (Its claim to fame is it’s the No. 1 cause of fatal mushroom poisoning worldwide.) This new outbreak is something different, though — an invasive cultivated fungus. As to where it is thriving, it could be where the release started, or it could be because temperature, humidity, and other factors are particularly conducive. She said they are investigating the question of whether the proliferation of golden oysters is crowding out other plants or fungi, or destroying animal habitat. They aim to have a paper ready in the next few months.

In June, the New Phytologist Foundation held a symposium on invasive fungi with conclusions about the ecosystem/biogeochemical consequences of such introductions forthcoming. From Reisdorf’s perspective, it’s unlikely we will know how GOM were introduced.

“There’s practically no way to get rid of it.”

“There’s a lot of lore about how this happened — a commercial outfit caught fire, or there was a tornado. But if there was one big introduction event, you would see that in the population genetic data. You’d see a cluster of similarity, and we’re not seeing that at all. We’re seeing extremely genetically similar specimens collected far apart.”

Reisdorf said this suggests multiple introductions of the same source strain in different parts of the country. But how that happened is still a bit of a mystery.

Pringle stresses the importance of citizen science websites like iNaturalist and Mushroom Observer in tracking movement and making a species more visible. But it’s an uphill battle.

“We have names for 5 percent of fungus species. Best estimates on how many species there are range from 2 million to 10 million, and they are hidden within soil, plant leaves, even animal bodies,” she said. “But there is such a thing as an endemic fungus, a place a fungus grows and where it doesn’t. So, moving them should be done thoughtfully.”