Companies like Corteva and Bayer are pushing to commercialize — and genetically engineer — soil microbes.

Consider the seemingly limitless number of living species on the planet — more than half of them are contained in healthy soils. Most are microbes: bacteria, fungi, protozoa and other microscopic organisms which, although invisible to the naked eye, are essential to agriculture, and fundamental to life on Earth.

These microorganisms play a critical role in the health, quality, and nutrition of our crops, and protect them against a wide variety of diseases, pests, and weeds. They help restore degraded soil, building its structure, and guard against floods and drought. Microbes also regulate the nitrogen and carbon cycles, playing a crucial role in capturing and storing carbon in the soil, thereby helping us combat climate change.

Hundreds of these naturally derived soil microbes or “biologicals,” traditionally used in agroecological farming, are now also applied to conventional production systems. Their market is worth almost $15 billion but, driven by growing consumer demand for healthier, more sustainable food, is expected to double in the next five years. As a result, huge agrochemical and biotech companies like Bayer-Monsanto, BASF, Syngenta, and Corteva Agriscience, are pushing to commercialize soil microbes, which they are genetically engineering to increase survival and efficiency in the soil.

Much like GMOs in other parts of agriculture and livestock production, genetically engineered (GE) microbes are proving somewhat controversial. At issue: We currently have little idea of the potential impacts these microbes could have on the soil microbial community and its vital functions. We understand the function of less than one percent of the billions of species of microbes in our soil, and even less about the interactions between these hugely diverse and complex communities. Yet the scale of release of these GE microbes is huge, and the odds of containment very small, with an application of GE bacteria releasing up to 3 trillion genetically modified organisms every half an acre.

A report by Friends of the Earth, titled Genetically Engineered Soil Microbes: Risks and Concerns, explores the potential implications of these microbes used in agriculture, and claims they are a cause for concern and a potentially serious threat to soil health.

Kendra Klein, deputy director for science at Friends of the Earth and the report’s author, said, “These are living organisms, put out into living systems — organisms that can replicate and are part of incredibly complex ecosystems that we understand very little about. We are releasing genetic sequences into the environment which have never existed before.”

Klein believes an extremely precautionary approach needs to be adopted when GE microbes are used in agriculture because the scientific evidence is uncertain, but the stakes are high in terms of human health and the environment.

“It’s reasonable to assume there will be some unintended consequences, but there is absolutely no system to monitor any potential impacts, or their spread in the environment, once released,” Klein explained. “Most microbes used in agriculture die off within a season, but if they are engineered to be more persistent, and last longer, they could become invasive and change the microbial community dynamics. And if they are pathogenic and persistent, then that could create enormous problems.”

“There’s no silver bullet or shortcuts to achieving a better functioning soil.”

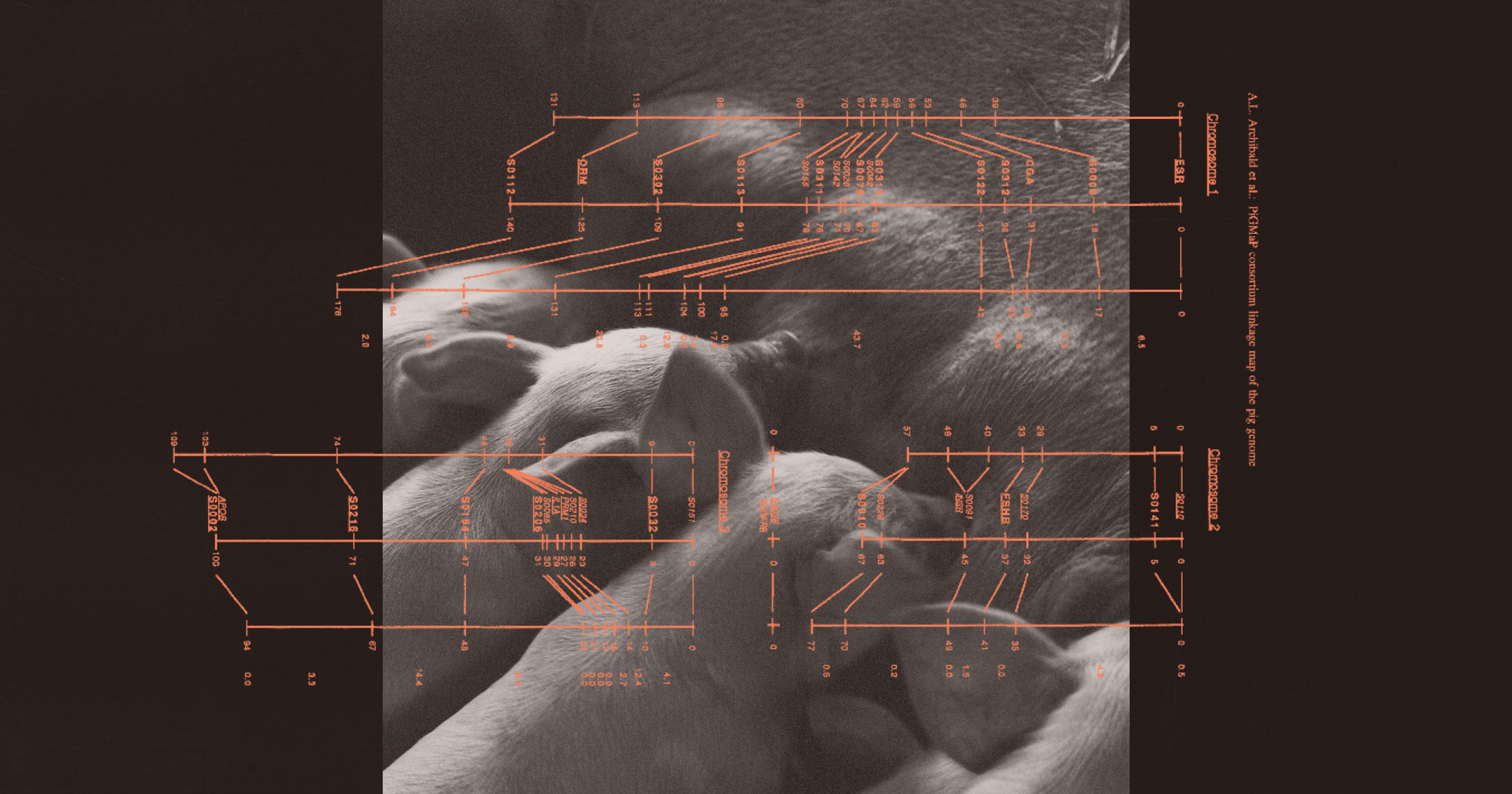

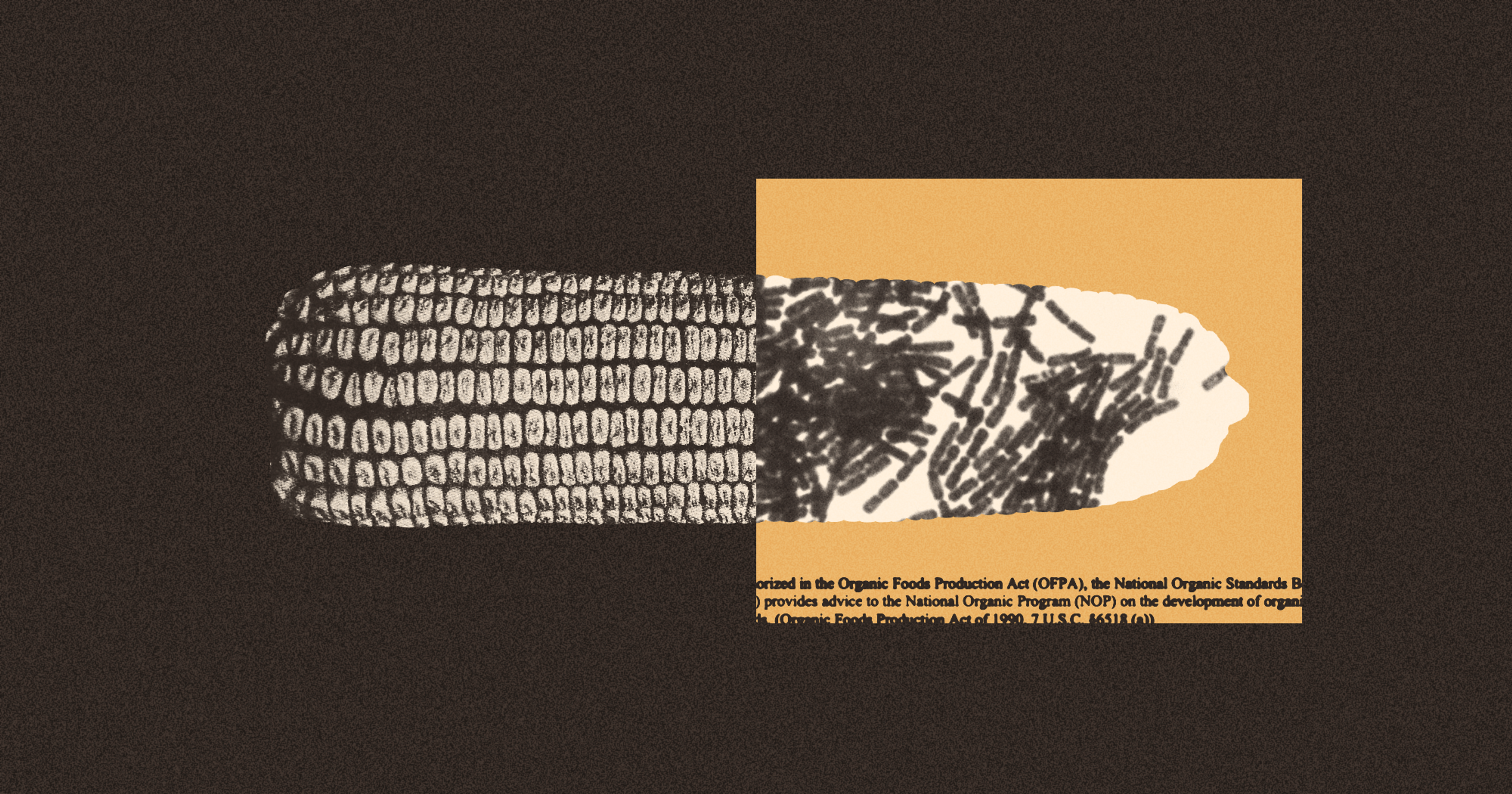

At least two genetically engineered microbes are currently used across U.S. farmland, primarily in monoculture corn production. BASF’s Poncho/VOTiVO 2.0 seed coating protects against nematodes using an insecticide known as clothianidin, while an added GE bacteria provides more nutrients and higher yields by breaking up organic matter around the root. Proven, a nitrogen-fixing, gene-edited bacteria from Pivot Bio, has had its natural ability to stop fixing nitrogen turned off. Currently used on more than five million acres of corn, this GE microbe is used alongside a reduced amount of the farmer’s traditional nitrogen fertilizer and, the company claims, contributes to healthier, more productive plants.

Mitchell Craft, director of communications at Pivot, said, “Pivot Bio’s microbes provide ammonium in small amounts on the roots of crops where it is directly taken up by the plant, avoiding nitrate leaching or volatilization into nitrous oxide. The microbes produce ammonium in exchange for sugars produced by the plant, which are their food source. When the crop dies, their food source goes away, and they die.”

As yet, we do not know what the consequences might be of releasing billions of Proven microbes across millions of acres of farmland. Research has shown if a legume, such as lentils, is swamped with nitrogen, the plant will down-regulate the colonization of its nitrogen-fixing bacteria. But Pivot Bio has eliminated the ability of these bacteria to sense they are in a nitrogen-rich environment, by eliminating the “off switch” for the microbe’s process for fixing nitrogen. The negative consequences could be significant.

Joseph Amsili is a soil scientist at Cornell University’s Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, and coordinator of the New York Soil Health Initiative. His work includes educating farmers about how practices which build up organic matter, such as reduced tillage and cover crops, help regenerate soils.

“It’s like the Wild West with all these biological inoculants and people making claims that theirs is going to do this and that for the farmer,” he said. “Just adding a microbial inoculant, and expecting that you’re going to get all the benefits down the line is potentially a poorer investment than focusing on rebuilding soil health using good sustainable management practices — whether that’s cover crops, manure, or reducing tillage.”

“We don’t have enough data from field trials, or even from a controlled environment such as a greenhouse, to know what will happen.”

“There’s no silver bullet or shortcuts to achieving a better functioning soil,” he added.

Developers of GE crops and microbes are allowed to self-designate unlimited amounts of information as “Confidential Business Information” (CBI), so many details about the nature of the product can be hidden from the public. Although the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website mentions they have registered eight different genetically engineered microbes as pesticides, according to Klein, Friends of the Earth researchers could not even identify which microbes have been commercialized or are in the pipeline, beyond the two mentioned here.

Referring to a letter sent by Pivot Bio to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), regarding its GE microbe, Klein explained that the entire 4-page table, which appears in the publicly accessible regulatory system, is completely blank because the information has been deemed CBI.

“Whether people are farmers, consumers, local communities, or conservation organizations, they need to be able to weigh in and collectively decide what’s okay. What are we willing to allow? What are the risks involved?” said Steven Allison, a microbial ecologist and climate scientist at the University of California, Irvine. “It’s hard with microbes, as we don’t have an existing framework. It’s uncharted territory, and we’re not sure about what the potential risks might be. We don’t have enough data from field trials, or even from a controlled environment such as a greenhouse, to know what will happen.”

Allison stressed the importance of having an evidence-based regulatory framework and said that, because the development of these GE soil microbes is still at an early stage, there needs to be more testing by industry and researchers to prove the benefits are real and the risk is tolerable.

“We need to see the evidence first — that they work, and aren’t too risky. For example, that there is a kill switch in your GE microbe that prevents it traveling too far, or to too many generations,” he said. “There are probably safeguards that can be built into this technology. These need to be in place and the data has to be collected, before I can tell you ‘Yes, this is a low-risk technology.’”

“It’s like the Wild West with all these biological inoculants and people making claims that theirs is going to do this and that for the farmer.”

Clearly the stakes of maintaining soil health are particularly high right now, in the face of relentless climate change. Soil is the basis of 95 percent of our food production. We clearly need to protect and regenerate soil, so we can continue producing food into the future, and so farmers can deal with the increasing droughts, floods, and extreme temperatures.

If a GE soil microbe could legitimately reduce the use of synthetic pesticide or fertilizer, without harming soil health or the ecosystem, this would have significant environmental benefits. But we know genetic engineering, even using techniques claimed to be “precise,” can result in unintended genetic consequences in organisms, and has the potential for profound and widespread changes.

Research has shown microbial inoculants can significantly disrupt and alter an already existing plant and soil microbial community, even when they die off quickly, by changing the overall diversity of fungal and bacterial species, and can cause visible changes to plant growth and insect communities, which are different from the intended effects of the inoculant.

Allison suggests that a more natural and effective evolutionary process could be used to manipulate the microbes in the soil, which might be lower risk and less invasive than the genetic engineering approach.

“By choosing the microbes that survive best, in the environment you want, generation after generation, after only a few weeks you might have microbes which are genetically distinct and performing differently — from natural selection, not genetic engineering,” he said.