Central Oregon’s irrigation canals, a vital lifeline to the region’s farmers, lose 30 to 50% of their water due to seepage and evaporation. Modernization is coming.

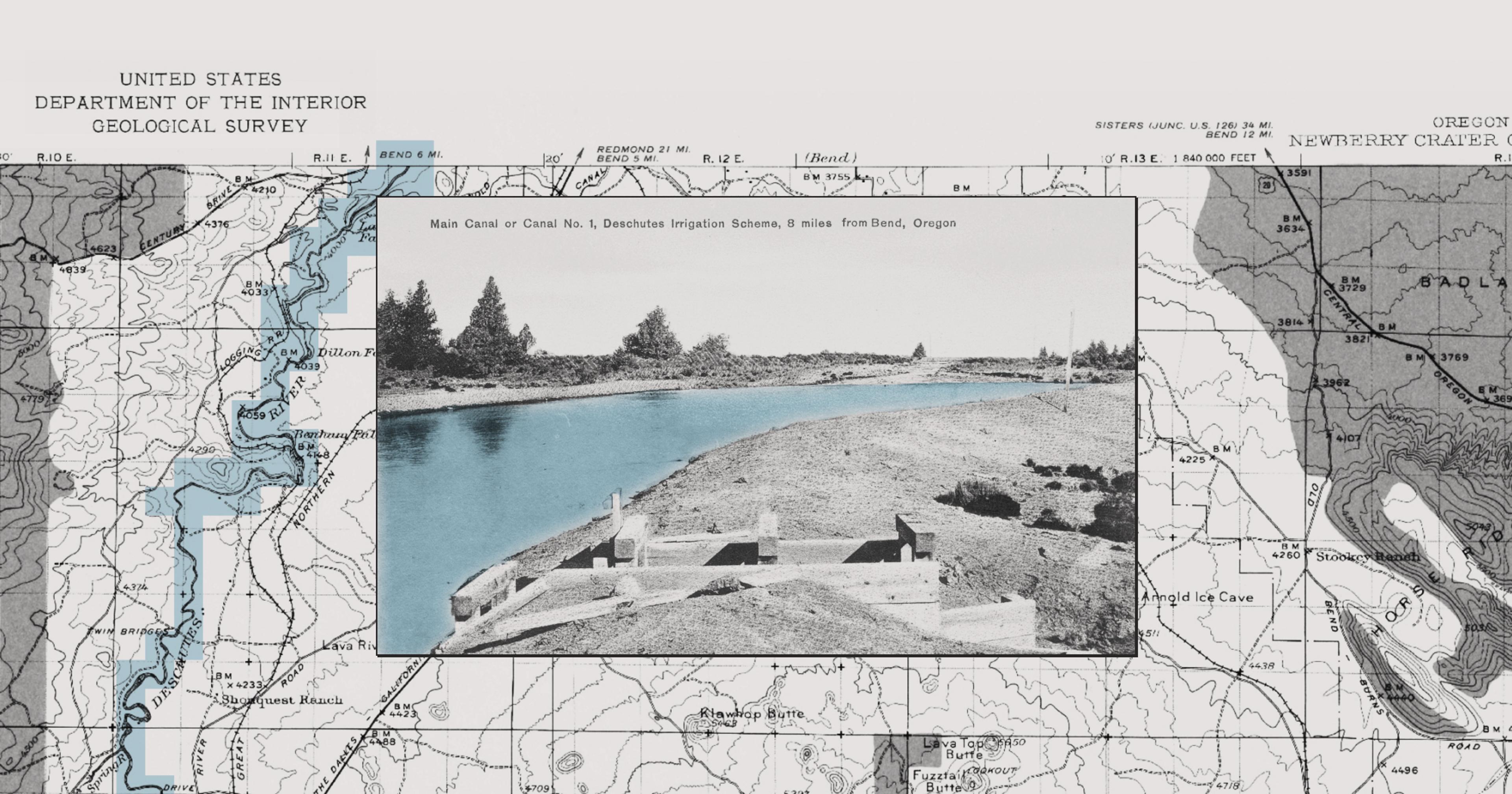

In the early 20th century, with an eye toward expanding cattle grazing and farming its high central desert, the state of Oregon, funded by the federal government, began to build its first large-scale irrigation systems. Rivers and streams were dammed to create reservoirs; unlined and open earthen canals were dug (or in some cases, wood flumes were built) to divert river water and release it over thousands of acres of farmland. Historically, Central Oregon has relied on about 80 inches a year of melting snowpack to recharge its rivers in spring; because of its otherwise low precipitation, agriculture would have been impossible here without irrigation.

Now, some of these systems in Oregon and elsewhere in the West are more than 100 years old — and their age is beginning to show. They serve water to communities of farmers and ranchers organized into irrigation districts — eight districts in the case of the Deschutes Basin. Farmers pay each district for water allocations that can run $100 or more per acre per year. The systems’ open irrigation canals also lose between 30 and 50% of their water to seepage and evaporation before it even reaches farm fields. The underlying infrastructure of these irrigation systems “worked out really well but [they] are aging and starting to show their wear and tear,” said Shiloh Elliot, a data scientist at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), a federal Department of Energy (DOE) lab that researches renewable energy solutions.

Many of them are due for costly overhauls but how to both tackle and afford them are daunting questions. Under the auspices of the DOE’s Water Power Technologies Office, INL and a sister DOE lab have devised software intended to help districts figure this out. They’re working off an Irrigation Modernization Program devised by a nonprofit called Farmers Conservation Alliance (FCA), which works with districts across the West to modernize irrigation systems. The hope of all involved: to create an irrigation model that can be “one size fits all, or at least is scalable,” Elliot said.

Leaky Systems

There were 1.7 million farm acres in Central Oregon as of 2017, mostly used for cattle and wheat, as well as for crops like potatoes and melons. Water in the region is becoming more and more of a precious resource, forcing farmers to seek emergency use permits from the state to pump groundwater. Because of climate change, “The natural environment that existed when those systems were established doesn’t exist anymore,” Elliot said. Snowpack from the Cascade Mountains has been dwindling, which means waters in the Deschutes River and elsewhere have been, too; this year, the state declared a drought state of emergency for Deschutes County for the third year in a row.

Complicating matters, the Deschutes River is home to three threatened species accorded federal protection under the Endangered Species Act: the Oregon spotted frog, bull trout, and steelhead. Under the terms of a Habitat Conservation Plan drawn up by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to accommodate public and private interests, Deschutes’ irrigation districts and other stakeholders have agreed to increase the River’s flow by almost 200% by 2028, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting.

This is one reason “there’s such an urgency and emphasis for these districts on, how do we prepare ourselves for these changing conditions,” said Marla Keethler, who works on FCA’s communications team. Mandates to protect federally listed species are often seen by farmers “as hurdles, and not received well. But what if we can open up opportunities for funding to support those species returning to levels that they need, and that funding benefits [farmers], too?”

In creating their software, which the INL website describes as “a decision-making tool … to help inform key decisions about modernization,” the DOE labs mined information collected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Geological Survey to understand things like “How much water is actually being lost out of a canal due to seepage? How much hydropower potential is there to this particular canal modernization?” Elliot said. That data can be used to understand what the components of modernization should look like. In some cases, it makes sense to replace a district’s open canals with underground pipes to eliminate water loss.

Additionally, depending on a district’s needs, dams might be removed to improve river flows, or special screens might be installed that allow districts to divert water without harming fish. The labs also help identify place-specific “multi-sector benefits, and what I mean by that is, do we have the potential to reduce some of the vulnerability of a remote community that may lose its power during fire season, because big transmission lines have to be turned off to prevent wildfires?” said Elliot. Laying pipe offers the chance to also lay down electrical infrastructure and/or establish microgrids to support community energy use.

Hydropower might also be introduced to bring in secondary revenue to an irrigation district. “If you can stick a turbine in a [water] pipe you can generate power,” said Elliot. Most of all, she said the group wants to figure out: “How do we make irrigation modernization approachable for the people who actually need to modernize the systems?”

Challenges Ahead

Finding money — and a lot of it — is essential because it costs about $1 million per mile of laid pipe to carry these projects out. FCA helps districts apply for local, state as well as federal funding, such as from USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Watershed Planning and Flood Prevention Program; they also secure private funding from companies like Google, which provided $120,000 to prototype a data management tool that tracks real-time water usage.

Still, the expense of updating is great enough that it renders the one-size modernization model impossible to fit to all — at least for the moment. For some cash-poor districts, a less long-lasting solution is to line canals with concrete or plastic membranes, to prevent seepage; and to cover them with solar panels, to cut down on evaporation.

Troy Peters, a biological systems engineer at Washington State University Extension, said that some communities rely on canal seepage to recharge their aquifers, making piping in these instances a non-starter. And piping can have unintended negative consequences. Years ago, farms in the Snake River Basin modernized their irrigation infrastructure. Afterward, “The aquifer started to drop a lot so some of these people that relied on these aquifers, like fish farmers, were like, Where’s my water? And they sued,” Peters said.

Peters sees benefit in educating farmers to use less water, no matter what sort of modernization an irrigation district opts for. “A lot of times they’re using more water than they need and leaching nutrients from their fields,” he said. “It’s definitely not in their interest to be over-irrigating, but it’s difficult for them to figure out when to turn the water on and when to turn it off.” Extension, state conservation districts, and to a lesser extent NRCS, are adept at passing this knowledge on — if only farmers will seek and heed their advice. Irrigation scheduling apps, such as one Peters developed, can also help determine things like crop water use rates and soil water holding capacity.

“Once you start to fix old systems and rethink how we’re managing water in that space,” said Keethler, “everyone gets some benefits from these modernization projects.”