For many years, most living history farms in the U.S. focused on the agricultural history of white Americans alone. A shift is underway.

At a site as large as Colonial Williamsburg, the world’s largest living history museum, chance encounters between its 1,500 employees happen all the time. Once such meeting, between Eve Otmar and Chris Custalow four years ago, led to a literally groundbreaking project.

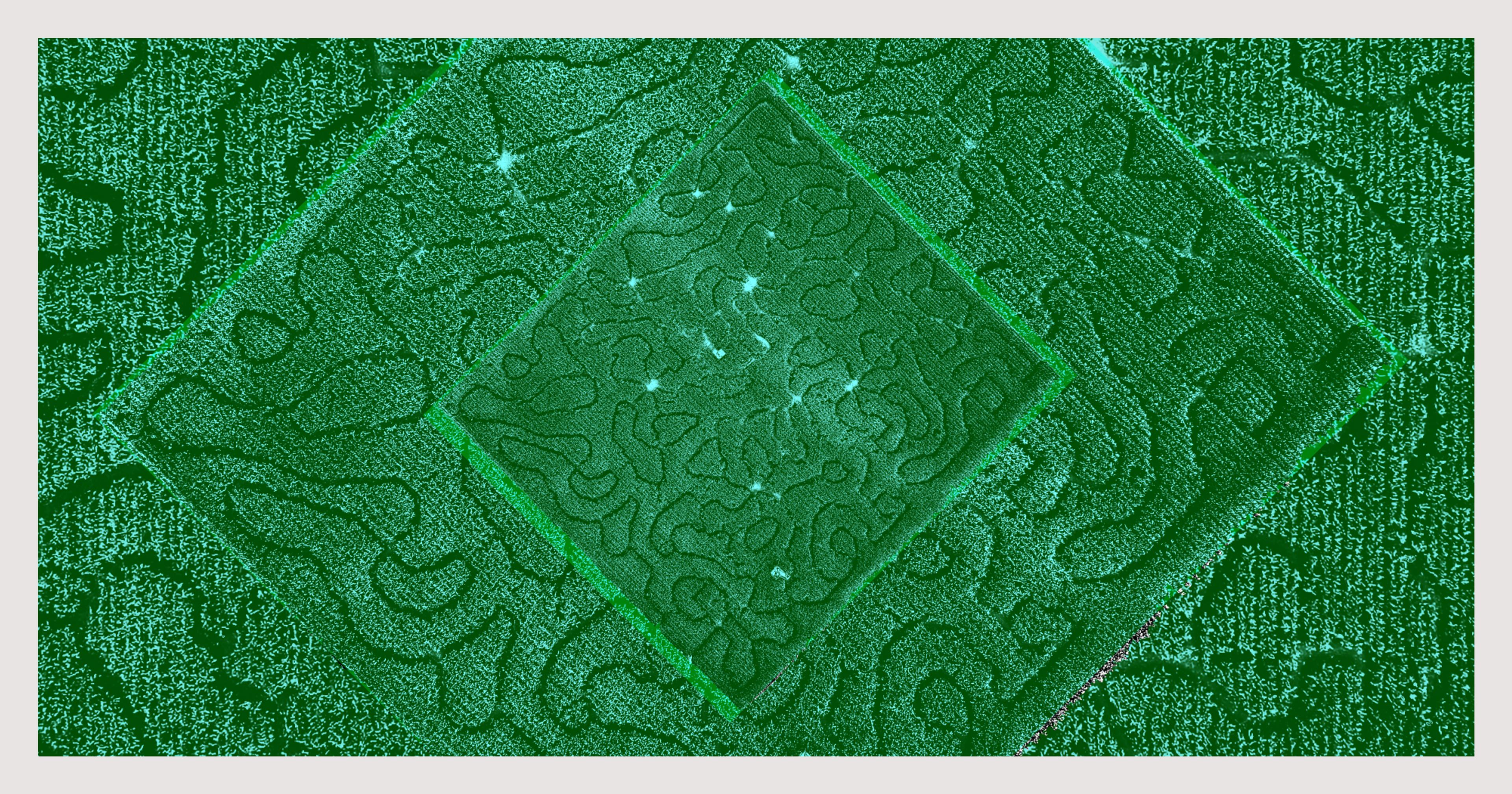

Otmar, the site’s master of historic gardening, had recently collaborated with storied African American culinary historian Michael Twitty to create the Sankofa Heritage Garden, a recreation of a garden enslaved people might have kept in 18th-century Virginia. As she talked with Custalow, the site’s Indigenous communities engagement manager, the idea of adding an Indigenous garden took shape.

“I never saw someone like me, working in an agricultural field — let alone at a museum, talking about their ancestral knowledge and teaching those things,” said Custalow, a member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. “Now we’re on our third season of growing traditional foods in the traditional agricultural methods of our ancestors.”

Over the last few decades, living history farms and museums in the U.S. have begun to highlight the stories of previously overlooked communities. Thanks to researchers and interpreters, the agricultural practices of Native Americans, African Americans, and Hispanics are reshaping our understanding of the history of American agriculture. And it’s coming at a moment when diversity initiatives in the workplace, the classroom, and in society at large are facing significant backlash.

“This is, dare I say, a revolutionary thing,” said Custalow.

Learning by Doing

The idea for the Sankofa Heritage Garden began with the closing of the museum’s Great Hopes Plantation, which featured historical recreations of enslaved houses and gardens. Twitty and Otmar, along with now-retired historic interpreter Robert Watson, planned and planted the garden in August of 2021. Crops included the Egusi melon from West Africa, okra, cowpeas (black-eyed peas), white eggplant (called Guinea squash), and tomatoes.

Sankofa, a word from the Twi language spoken in Ghana, comes from a longer proverb that says we should not hesitate to go back for something we forgot in order to move ahead. In short, Sankofa embodies the best intentions and possibilities of historical interpretation, which scholars say “brings the lives and experiences of a past age into the modern era to provide a contextualized interpretation of long-gone cultures.” The Three Sisters Garden came along a year later.

When in full bloom, it can be difficult to tell the Sankofa and Three Sisters gardens apart. Both feature mounds or hills of the traditional Indigenous triad of corn, beans, and squash, a method also known as companion planting. Beans climb and stabilize the corn stalks, while squash keeps moisture in the soil and keeps out weeds. As Custalow explained, scooping the rich topsoil into hills also gives the plants maximum exposure to its nutrients — particularly important in a place like Virginia where the topsoil layer quickly gives way to clay.

Of the two gardens, Sankofa’s hills tend to be higher. According to Otmar, their greater height reflects the drier conditions in West Africa, where most enslaved people in 18th-century Williamsburg learned how to grow food. Otmar and Twitty also accounted for the historically limited time there was to tend these gardens and only weeded once a week — to great success. “We barely had to touch that garden,” said Otmar. “It kept the moisture longer. It grew incredibly well.” She and the other gardeners still adhere to that schedule.

To determine what to grow, Otmar uses a blend of written records and archaeological research. Take the peanut. Before a housing development was built on the grounds of a former plantation near Colonial Williamsburg, archaeologists unearthed centuries-old peanut shells where the enslaved quarters used to be. Otmar added peanuts to Sankofa’s rotation.

While their first peanuts suffered from a cold spring and late frost, Otmar has had better luck with Bambara groundnuts, the third most important legume in Africa after the peanut and the cowpea. Meanwhile in the Three Sisters Garden, she and Custalow have planted muscadine grapes, Jerusalem artichokes, paw paw trees, prickly pear cactus, and even sunflowers, the heads of which Custalow says are delicious fried with just a touch of salt and pepper.

Many of the Sankofa’s heritage seeds come from Truelove Seeds in Philadelphia and the Roughwood Center for Heritage Seedways. In the Three Sisters Garden, however, seeds often come directly from Native communities. Custalow has brought seeds back to Colonial Williamsburg from the Saponi nation in the Virginia and North Carolina piedmont, as well as the Choctaw and Cherokee nations in Oklahoma. They not only plant the seeds in the plot but also send seeds back after growing them out to help Native communities increase their yields. It’s this aspect of the American Indian garden that Custalow finds most rewarding.

“Right now, the agricultural movement within Native nations is really big,” he said. “It’s only in the last five to 10 years that these people have really been able to … produce larger quantities of food that allows them to approach food sovereignty.”

Cultural Sustenance

“Food and language are the two things that hold our history,” said Jennifer Frazee, a biracial member of the Choctaw nation and director of Fort Gibson, a 19th-century army fort in eastern Oklahoma that played a role in the Trail of Tears. “Whenever you’re learning the process of food, the ceremonies that go behind food, the making of it, and all that, you are learning the culture of that people in a way that you would never do just by reading the recipe out of a book.”

Frazee began her career in living history museums as an interpreter at Hunter’s Home, Oklahoma’s only surviving antebellum plantation. In fact, it was a visit to Colonial Williamsburg in 2015 that inspired her to highlight untold agricultural stories.

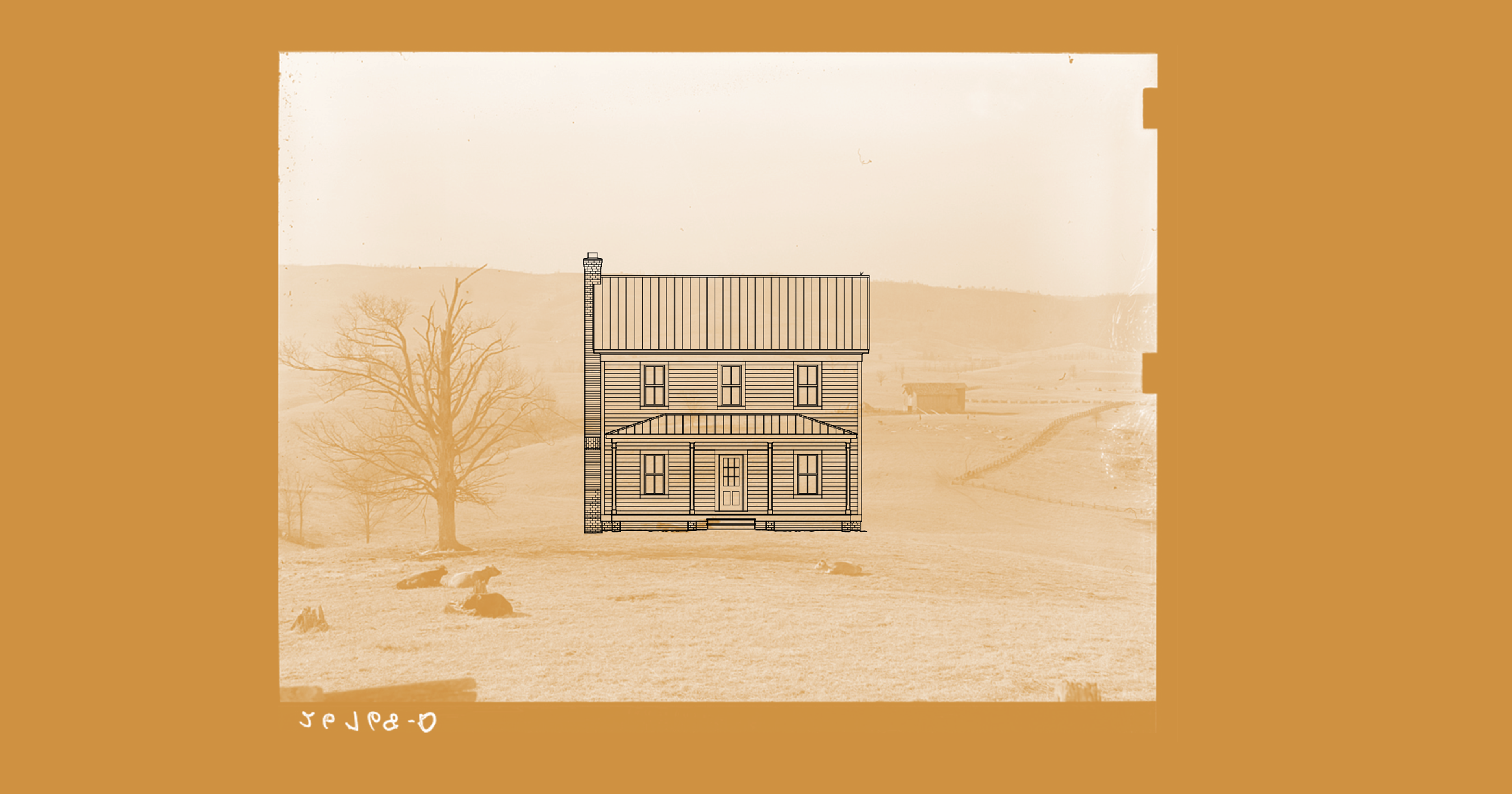

One of the most notable changes to the plantation site came in 2018, when the site changed its name from the George M. Murrell Home back to Hunter’s Home, the name given to it upon its completion in 1845. George Murrell was a white Virginian who came to Oklahoma because of his wife, Minerva Ross Murrell, a half-Cherokee woman forced to relocate during the Trail of Tears. Moreover, since the Cherokee nation is matrilocal, the actual owner of the property was Minerva, not her husband.

“We’re at this Cherokee site, this Cherokee plantation, the only one in Oklahoma that we have left. And all we’re talking about is this old white guy that really had nothing to do with it,” said Frazee.

Frazee was able to bring her educational expertise as well as her lived experience to Hunter’s Home. She grew up on an allotment given to her family in 1903, one of the most significant waves of forced relocation for the Choctaw. “What I saw was Native American agriculture. That’s all I knew,” she said. Frazee remembers her grandfather having a kitchen garden at the back of the house for tomatoes, peppers, and herbs. From him, she learned to rely not on gardening manuals but on spiritual practices and collective knowledge passed down through generations.

If the grass turned purple due to a lack of phosphorus, for instance, they would make offerings of eggshells and banana peels, both good sources of the mineral. She still puts sardines (which provide nitrogen, phosphorus, and other fertilizing nutrients) in the soil whenever she plants a tree on her own home.

“We’re at this Cherokee site, this Cherokee plantation, the only one in Oklahoma that we have left. And all we’re talking about is this old white guy that really had nothing to do with it.”

At Hunter’s Home, she and the other employees would lay down tobacco to ask for a favorable harvest before planting. Whenever possible, the site’s employees use seeds from the Cherokee Nation’s seed bank for their companion planting and raised beds. The heritage breed of Dominique chickens also provides meat, eggs, and feathers to recreate historical clothes and bedding. When they graze, they turn and fertilize the soil.

There is a darker side to the history of Hunter’s Home, however. Minerva’s overseeing of the plantation included approximately 40 enslaved people brought from Virginia to Oklahoma. Hunter’s Home staff do not shy away from this reality, but they acknowledge its complexity.

“She was the product of a policy of assimilation,” said Frazee of Minerva, explaining that intermarriage was a way for white settlers to disrupt and erase Indigenous cultural teachings.

“Traditional culture is about community. It’s about everybody working for each other and taking care of each other. And there is no place for slavery in that,” she said.

Controlling the Narrative

“Agriculture and its enslaved component cannot be disconnected from the economic development of America — and particularly the economic development of Texas,” said Naomi Carrier, a playwright, composer, historical interpreter, and founder of the Texas Center for African-American Living History in 2007.

Since the 1980s, Carrier has been commissioned by various places to write and perform plays about the lived experience of African Americans in Texas. Fifteen of these plays, most of which dramatized the experience of enslaved African Americans from 1821 to the end of the Civil War, were collected in her 2010 book ‘Go Down, Old Hannah’: The Living History of African American Texans. But her last commissioned performance was in 2017.

“The political climate [now] is not open to the work that I did,” she said, referencing the reactionary turn in the last decade of Texas state politics. “I am developing my grandfather’s and grandparents‘ property into a living history farm because I am not allowed to tell this story as I once have on these state-owned farms.”

“The political climate now is not open to the work that I did.”

Fortunately the Texas Center for African-American Living History allows Carrier to tell this history on her own terms — and turf. “My vision for that space is to interpret some of the reenactments in my book and also how cotton and sugar was essential to the lives of my family,” she said. The center is housed in a building constructed by her grandfather, Marshall Mitchell, on the property in Lavaca County that he and his wife Malinda purchased in 1917. (Carrier successfully lobbied to have a historical marker placed on the site.) Mitchell not only built the family home but also a school, a church, and a sugar mill. “At harvest time, in the fall, wagons would be lined up full of sugar cane for my grandfather to turn that into molasses,” she said.

Carrier also recalls her aunts and uncles having to pick cotton before school to help their families survive. She is reminded of this reality every time she drives out to the property: “Sometimes the fiber from the cotton is so thick that it almost looks like fog.” Inside the house, she has her grandmother’s teaching certificate, an old sewing machine, and other artifacts from her grandparents’ time.

As a one-woman operation, building out the programming will take time, especially since Carrier is helping with other projects, such as assisting with efforts to get national recognition for the Columbia Tap Trail in Houston’s Third Ward, a 4-mile stretch of former railroad built by enslaved people to transport sugar and cotton.

“You can only memorialize with respect and preserve what you love. But you can only love what you’ve learned,” she said.

Hands-On History

According to Sean C. Paloheimo, assistant museum director and director of operations at El Rancho de las Golondrinas outside of Sante Fe, New Mexico, visitors are increasingly interested in connecting with — and potentially adopting — the agricultural practices of the past. “We’ve gone from a place where people are like, ‘Oh, that’s it you used to be done’ to people saying, ‘Oh, it can still be done that way,’” he said.

El Rancho is the largest living history museum in the state and sits on a former trading post and paraje, or official rest stop, on the El Camino Real (Royal Road) that ran 1,600 miles from Mexico City to north of Santa Fe. Home to heritage gardens, residential and trade buildings, historic mills, and livestock, the site shows how Indigenous nations, Spanish colonizers and their Hispano descendants, and white settlers interacted and influenced each other.

The most prominent example of a traditional practice still in place at El Rancho is its acequia, or community irrigation ditch. When the Spanish arrived in the 1590s, they drained the marshland in the valley where El Rancho sits and built these ditches based on technology learned during the 8th-century Moorish occupation of Spain.

“We try to get people’s hands dirty.”

These acequias are the earliest non-Indigenous form of government — with seven hundred still active in modern-day New Mexico — as well as the oldest water management organization in the U.S. Paloheimo sits on the commission for the La Cienega Acequia, whose section on El Rancho property dates from around 1715. “All of our crops that we grow here are irrigated in that historic flood irrigation way.” While flooding the area may seem less efficient and more wasteful than newer precision irrigation systems, Paloheimo has discovered that “by flood irrigating, you’re actually putting more moisture into the aquifers,” providing water to the whole ecosystem and not just individual plants.

The historic garden watered by the acequia features many of the same plants found at Colonial Williamsburg, including beans, corn, watermelons, pumpkins, green chili, and eggplant, as well as punche, a native tobacco. Livestock manure fertilizes the plants. Some of their most popular programming are the historical demonstrations and classes, including making molasses from sorghum rather than sugar. “We try to get people’s hands dirty,” said Paloheimo.

A Fragile System?

Over time, the living history stewards have lost some of the knowledge they used to impart. Take the mills at El Rancho. Historically, they were powered by burros to crush the sorghum cane. Before the pandemic, a Hispanic family handled burros for the demonstrations. But they stopped coming after the shutdowns, and the site has not been able to train any other volunteers to handle the animals. “You’re working with an animal that can kick. It’s a precarious thing for one of our retired volunteers to take on,” Paloheimo said. They now use human power to turn the mills.

“It really is a fragile system,” he said.

The same might be said of the attempts by living history museums to increase the diversity of their agricultural interpretations, even as the acronym “DEI” has been weaponized against inclusiveness. When Frazee would tell people about Minerva’s role in the history of slavery, some visitors would ask, “If you have Cherokees that owned slaves, then why should we bother with giving them the rights back to their land?”

Both Frazee and Otmar, as white-passing and white women, also acknowledged that they are not always the ideal messengers for Black history. However, Frazee also noted that many Black interpreters do not get the level of support they need. “It’s all good and well for us to make a position and hire a Black interpreter — but how do we make sure that they’re not going to have to deal with bull when they’re doing their job?” Frazee said.

“Young kids, Native or non-Native ... it’s changing the way that they’re seeing the world and who they can be or what they can do.”

Carrier acknowledged the toll this work can take, noting, “This history has left me with a lot of trauma. There is a very powerful movement to conceal the violence, the terrorism, the trauma, and the achievements, and the resilience and the overcoming of every obstacle,” of African Americans, she said. Nevertheless, “I can declare freedom for myself. It’s not something you can give me.”

But learning this history can give people a whole new sense of understanding of themselves and their heritage. Otmar recalled an exchange with a young Black woman at the Sankofa Garden about the practice of planting hot peppers on the outside of their gardens — a practice enslaved people brought from Africa, where the smell keeps animals out of the other crops.

“She goes, ‘My grandmother taught me to do that,’” Otmar recalled. But the young woman had been told that they planted the peppers not to keep out animals but to ward off evil. “The tradition was still in their family and still being passed on, but they’ve long since forgotten where it came from.”

But despite some losses over time, Custalow said, “Young kids, Native or non-Native, get to see these concepts and see these communities and the crops themselves growing here. It’s changing the way that they’re seeing the world and who they can be or what they can do.”