As American sod farmers start voting about whether to join USDA’s checkoff programs, sharp lines are drawn between yeas and nays.

On January 13, 2025, a month’s worth of voting commenced to determine whether America’s sod farmers will get their own checkoff. At least in theory.

Several days earlier, Carolyn Sherry, who runs a 1000-acre sod and calf-cow operation in Yukon, Oklahoma, with her husband, Brad, still hadn’t received her ballot in the mail. She was skeptical it would turn up. In fact, she was skeptical about pretty much everything related to a sod checkoff: how legitimate it was for the fescue, Bermuda, and Zoysia grasses their farm grows by seed and sells by the roll; how fair and transparent distributing and counting ballots would be; or the program’s actual utility for sod farmers.

“Our main challenges are weed control and weed resistance to chemicals over time … but we feel like we’re handling our problems pretty well,” Sherry said, referring to the sod checkoff referendum as an attempt at “democracy through bureaucracy.”

“We don’t have any complaints we want USDA involved in,” she added.

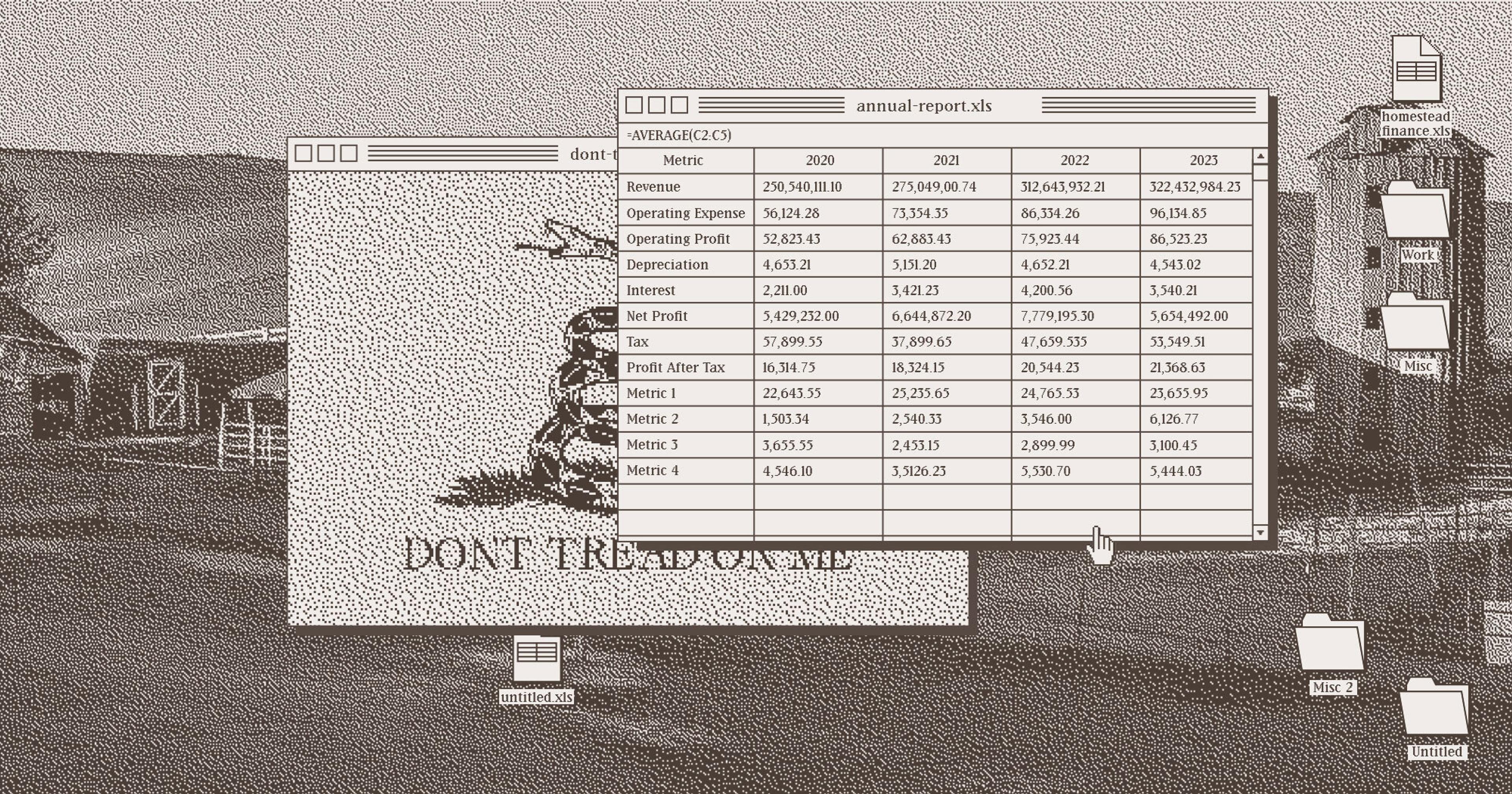

Checkoff programs are run by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Agricultural Marketing Service and they are a contentious business, as we reported back in 2023. They require mandatory fees from all producers of an enrolled agricultural commodity — 22 in all at the moment, including beef, eggs, and popcorn, with exemptions for Certified Organic. The programs have been challenged in court, most significantly on First Amendment grounds.

“The basic principle argument was that I, as an individual, object to the government requiring me to pay for speech with which I disagree, which in general is not allowed,” explained Harrison Pittman, director of the National Agriculture Law Center at the University of Arkansas. Additionally, certain of the checkoff boards have been accused of fund mismanagement.

Despite the contention in other checkoffs, Turfgrass Producers International (TPI), a trade group representing 350 of the estimated 1,500 sod grass producers in the U.S., has determined that a checkoff will help their industry weather various challenges. They’ve spent the last five years trying to convince their colleagues that a vote for checkoff is a vote for a brighter, soddier future. They’ve already got a slogan, “Keep It Real” — an unsubtle dig on the fake turf industry.

A sod checkoff would extract from every producer a fee (critics call it a tax) of 1/10th of a penny per square foot, or a little over $43 per acre harvested. All collected funds would be earmarked for sod marketing and research and portioned out by an 11-member board. “We used to have auctions and events and maybe we’d raise $75,000, $100,000 in a good year” for those purposes, said Bob McCurdy, a West Tennessee sod and row crop farmer who served on TPI’s board for six years; he grows warm season hybrid Bermuda and Zoysia root stocks planted by a method called sprigging. “That’s not enough to fund anything.”

“We don’t have any complaints we want USDA involved in.”

When checkoff discussions began, he was firmly in the anti camp, balking at what he considered government interference. Eventually, he was convinced that a checkoff would be a big help to American sod farmers, helping the industry as a whole gain greater appreciation among the public and the producers themselves “sell more grass, and that’s pretty important,” he said.

McCurdy believes American consumers have been fed the erroneous notion that natural turf is too water- and chemical-intensive to be environmentally sustainable. He said that has contributed to more urban and suburban landscapers — the biggest purchasers of sod; it’s also used for sports complexes and golf courses — choosing artificial turf. The Sherrys, however, dispute that plastic turf is a threat to their business. They note that a number of municipalities and states have moved to ban fake turf over concerns about heavy metal and PFAS contamination. “The artificial turf problems in California of toxins in the water runoff are taking care of itself,” wrote Brad in an email.

Still, it’s difficult to compare the broad ecological footprint of sod versus plastic turf. A 2024 report prepared for Montgomery County, Maryland, to determine which was preferable for its athletic fields noted that a natural grass field could use 1.5 million gallons of water per acre per year, for example. They also found that artificial turf needed plenty of watering, too, for cleaning and cooling purposes — in addition to the environmental risks it poses to waterways. It’s also a challenge to understand how much of a threat artificial turf truly is to natural grass. Artificial turf was valued at $2.7 billion in North America in 2020; the sod industry was valued at $2.2 billion in 2022, up from $1.5 billion in 2017. Both industries predict increases in sales over the next five years.

To battle what he sees as a two-headed negative force, McCurdy would like for an estimated $14 million in annual checkoff receipts to pay to disseminate the positives of real grass turf: The industry claims this includes carbon storage, oxygen production, and soil erosion prevention. And the negatives of plastic turf: its toxicity, high maintenance requirement, and the need to be replaced. “Most people who put an artificial field in don’t realize that in eight to 10 years they’re going to rip that thing up,” McCurdy said. “Every high school I go to has got a pile of it sitting back there, hoping lightning strikes it.”

“Almost all people irrigate their lawns in an incorrect manner, therefore producing a false image that grass is a heavy water user … The sod checkoff can generate a VOICE that is currently absent.”

An unscientific sampling of the 72 public comments left on the sod checkoff docket before voting started seemed to indicate strong support for the program. Lindy Murff, a Texas sod farmer and TPI board member, wrote, “Almost all people irrigate their lawns in an incorrect man[ner] therefore producing a false image that grass is a heavy water user … The sod checkoff can generate a VOICE that is currently absent.” Derek Tjaden, farm manager for Lawrence, Kansas’s, Sod Shop, felt checkoff dollars could support needed new varieties of sod as well as non-biased field research. In a similar vein, a golf industry representative named Chava McKeel wanted to use checkoff funds “to gather more national, state and local research focused on the value of ecosystem services, smart irrigation, drought tolerance, low-input grasses, etc. that turfgrass provides.” Members of Rutgers University’s turfgrass program were highly in favor of checkoff, as it would give them necessary funds, they wrote, to expand their research to improve sod production and develop new cultivars.

In fact, support of research programs is where the true value of checkoff lies, said Pittman. “I’m in the research and extension part of the university system, and a lot of our budget derives from checkoff programs,” he said. “Frankly, without them, from a land grant university perspective, I don’t see how we would have the incentive to maintain equipment, to maintain land, to maintain research plots, to maintain human resources, without those research dollars coming in.”

There is no shortage of contrary opinions about a checkoff program, though, or the way it would be managed. “I’m against one farm one vote,” wrote someone named William Popek about checkoff referendum procedures that give out one vote per farm EIN number. “If the larger burden is going to be on larger farms to keep this program going, then acreage should be considered.” Anonymous complained that the checkoff would come with “additional procedures to regulate and tax sod growers.” A trade group called the American Sod Farmer Coalition, which appears to have emerged with the specific intent to fight the checkoff, called the program unequal in its benefits, lacking in transparency and accountability, and an “immoral … form of theft.”

At the moment, it’s all but impossible to predict which way the sod checkoff winds will blow. Voting concludes on February 11, 2025. At the time of this writing, the Sherrys had finally received their ballot and would be voting No. Time will tell if their colleagues are with them or against them.