Climate change is forcing some winemakers to move north. But others are moving into the arid Utah desert, using water conservation and specialized grapes to make it work.

As climate change warms our world, winemaking in some regions has been shifting northwards. But in Utah, where cutting-edge technology, resilient grape varieties, and innovative farming techniques have converged, some growers are thriving in the driest of terrains.

A surprising agricultural story is taking root in southern Utah, where scorching summers and stark sandstone cliffs define the landscape. At roughly 37-38 degrees north latitude, on par with Valencia in Spain or Tuscany in Italy, and at elevations that expose vines to intense ultraviolet radiation, a small but determined community of vintners is mastering the art of winegrowing.

Once considered too hot, too dry, and too high for cultivating premium grapes, these arid fields now produce wines that regularly stand out in blind tastings. How are Utah’s vintners overcoming thin soils, limited water, and climate extremes to make a mark in American wine?

The answer lies in a blend of historical wisdom, scientific innovation, and persistence.

A Heritage Revisited

The idea of winemaking in the desert of Utah isn’t new. In the 1860s, early Mormon pioneers planted vineyards for sacramental wine, proving that grapes could flourish here under careful stewardship. But as attitudes shifted toward temperance, those vineyards withered and the region’s winemaking dreams lay dormant for generations. Fast forward to today, and renewed interest — spurred by tourism, entrepreneurial growers, and broader consumer curiosity — has revived the craft.

Michael B. Jackson, owner of Zion Vineyards in Leeds, arrived in 2012 and was astonished to discover a legacy waiting to be reclaimed. “The early Mormons had 650 acres of vineyards here,” Jackson said. “We’re now at just 1/10th of that, but we’re rebuilding.”

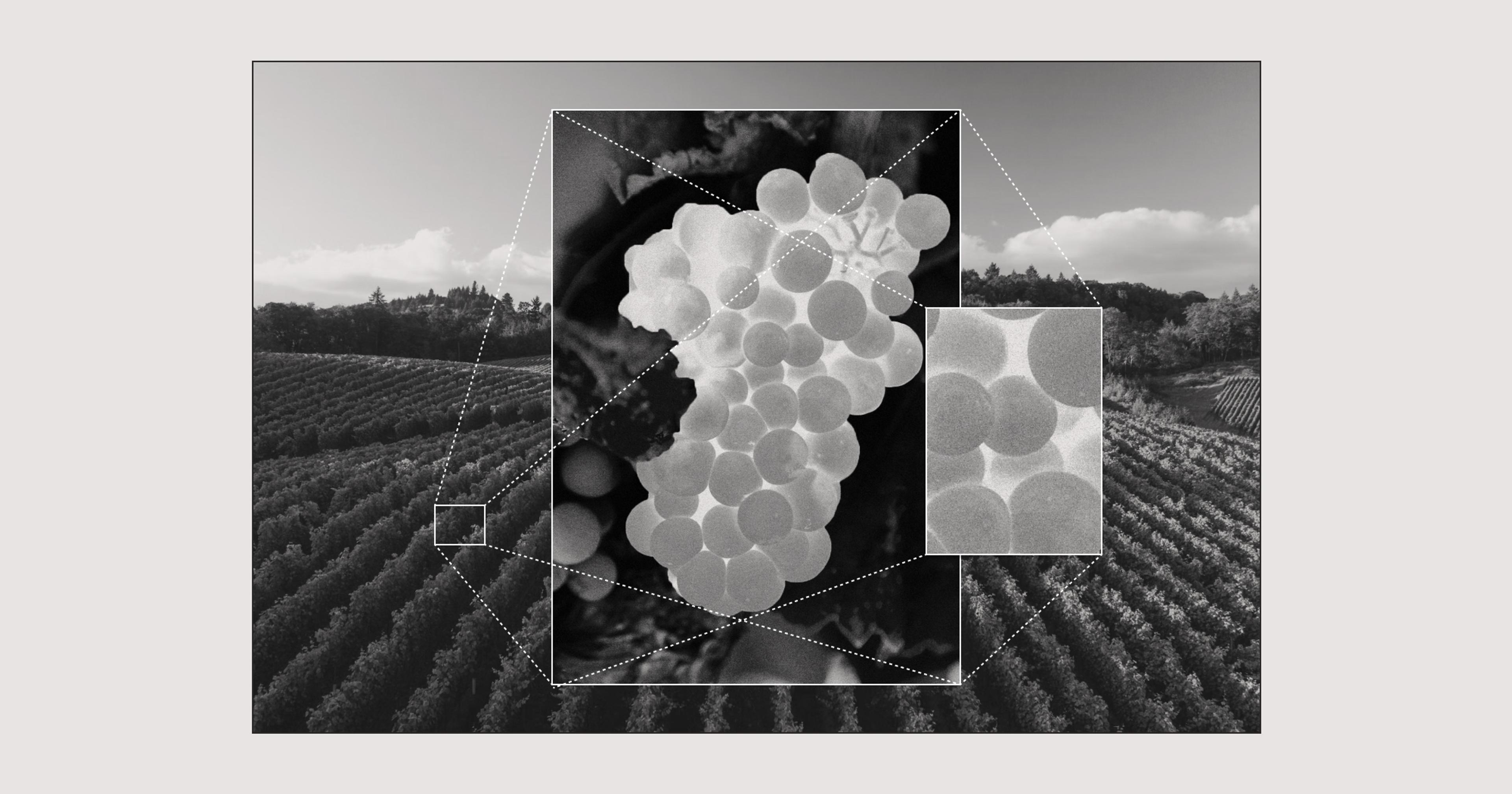

The high-elevation fields near Cedar City and Leeds face a suite of environmental hurdles. Volcanic soils rich in potassium require careful nutrient management. High altitude intensifies sunlight exposure, and desert air can push temperatures to extremes. Vines must be chosen and tended with these conditions in mind, balancing the delicate equation of heat, sunlight, and vine stress.

To make informed decisions, growers rely heavily on local expertise and research support from Utah State University. Testing soils, measuring radiation, and analyzing temperature fluctuations provide data that inform choices ranging from which grape varieties to plant to the precise timing of irrigation. USU’s Extension programs and collaborative research efforts have been central to equipping vintners with the tools to succeed in Utah’s challenging environment.

Doug McCombs, owner of IG Winery in Cedar City, explained that the extension is leading the way on research.

“They’ve done water, soil, water and soil sample studies to establish baselines. And they’re beginning that research now, so that they can, as years go by, have a real good database on which to begin working through some of these issues,“ he said.

One significant contribution is USU’s work in identifying grape varieties suited to the state’s extreme conditions. By evaluating cold-hardy and drought-tolerant cultivars, researchers have provided critical insights into which vines are most likely to thrive. These studies take into account factors such as survival rates, fruit yield, and optimal harvesting times, enabling growers to tailor their practices to Utah’s unique climate and soils. For example, specific grape types have been shown to withstand the region’s thin soils and high UV exposure, which might otherwise limit production quality.

Additionally, USU supports cutting-edge projects like the Grape Remote-sensing Atmospheric Profile and Evapotranspiration eXperiment (GRAPEX). This initiative uses advanced remote-sensing technology to monitor vineyard water usage, helping growers optimize their irrigation schedules. In a state where efficient water management is vital, such tools are transforming how farmers balance sustainability with productivity.

Precision in a Parched Environment

Water scarcity is obviously the defining challenge of agriculture in the desert. While some traditional crops thirst for large volumes of water, grapes have proven more efficient. Still, vintners must deploy smart tactics to make the most of every drop.

McCombs explained that efficiency is key: “If we have ample water, and the temperature’s not a million degrees, we can do quite well here.”

This efficiency comes through advanced irrigation management. Drip emitters deliver precise doses of water directly to the vine’s root zone, reducing evaporation. Soil moisture sensors are checked daily or weekly and signal when vines truly need water.

Weather stations track temperature, humidity, and wind. Armed with this data, a grower might apply water in shorter, more frequent intervals during peak heat, or cut back by a certain percentage late in the season when vines require less.

“We’re experimenting with desert weeds as ground cover,” Jackson noted. “It’s unconventional, but it helps hold moisture and reduce evaporation.”

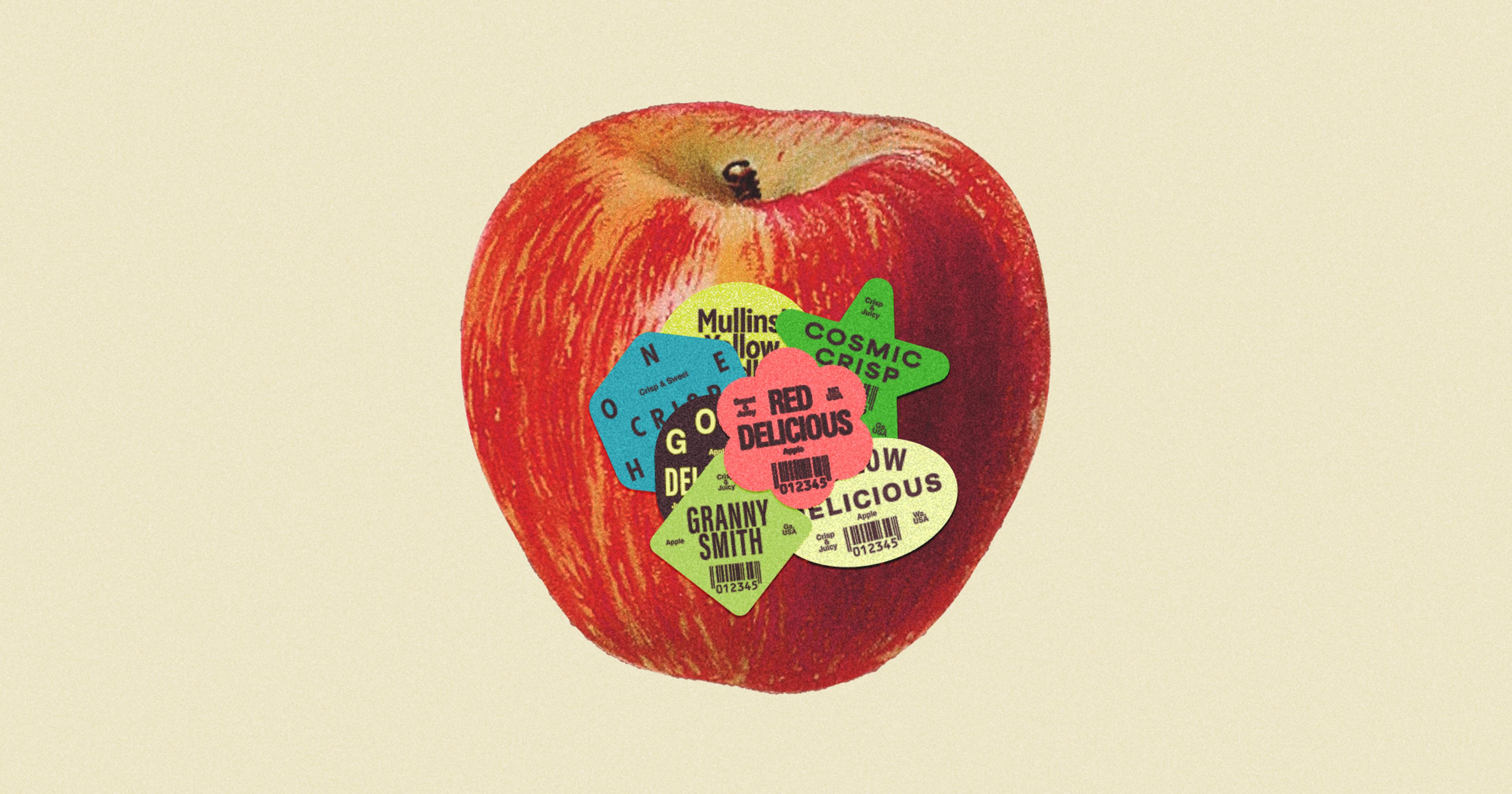

As growers gain confidence, they are also turning to grape cultivars that thrive in extreme heat and dryness. Spanish and Italian varietals, well-suited to Mediterranean and continental climates, have proven especially adaptable to Utah’s challenging conditions. Leading the way are the Albariño, prized for its bright acidity, and the Tempranillo, celebrated for its robust structure. These varietals produce grapes with thick skins and balanced sugars, enabling them to endure the region’s intense sunlight while yielding wines of remarkable character.

“We’re sticking to varietals that handle the heat and elevation,” Jackson said. “They’re not just surviving; they’re actually thriving.”

Volcanic soils in Utah impart subtle mineral notes, and the dramatic day-to-night temperature swings preserve acidity and aromatic intensity. Add a dash of altitude, and you get wines that marry lush fruit flavors like ripe peach in Albariño, and dark cherry in Tempranillo with lifted aromatics and a structured acid backbone. Tastings often reveal surprising complexity. For instance, a Utah Albariño might present bright citrus upfront, evolving into stone fruit and a whisper of minerality, while a Tempranillo could showcase red plum, subtle spice, and a lingering finish that speaks to the region’s high-elevation conditions.

Local wineries have noticed that educated drinkers appreciate these nuances. “Our Merlot has beaten big labels in blind tastings,” McCombs shared. “Once we find the sweet spot, the quality is undeniable.” Sommeliers and wine educators, intrigued by the novelty of these emerging vineyards, have praised their distinct personality, citing a fresher, more aromatic style compared to warmer lowland counterparts.

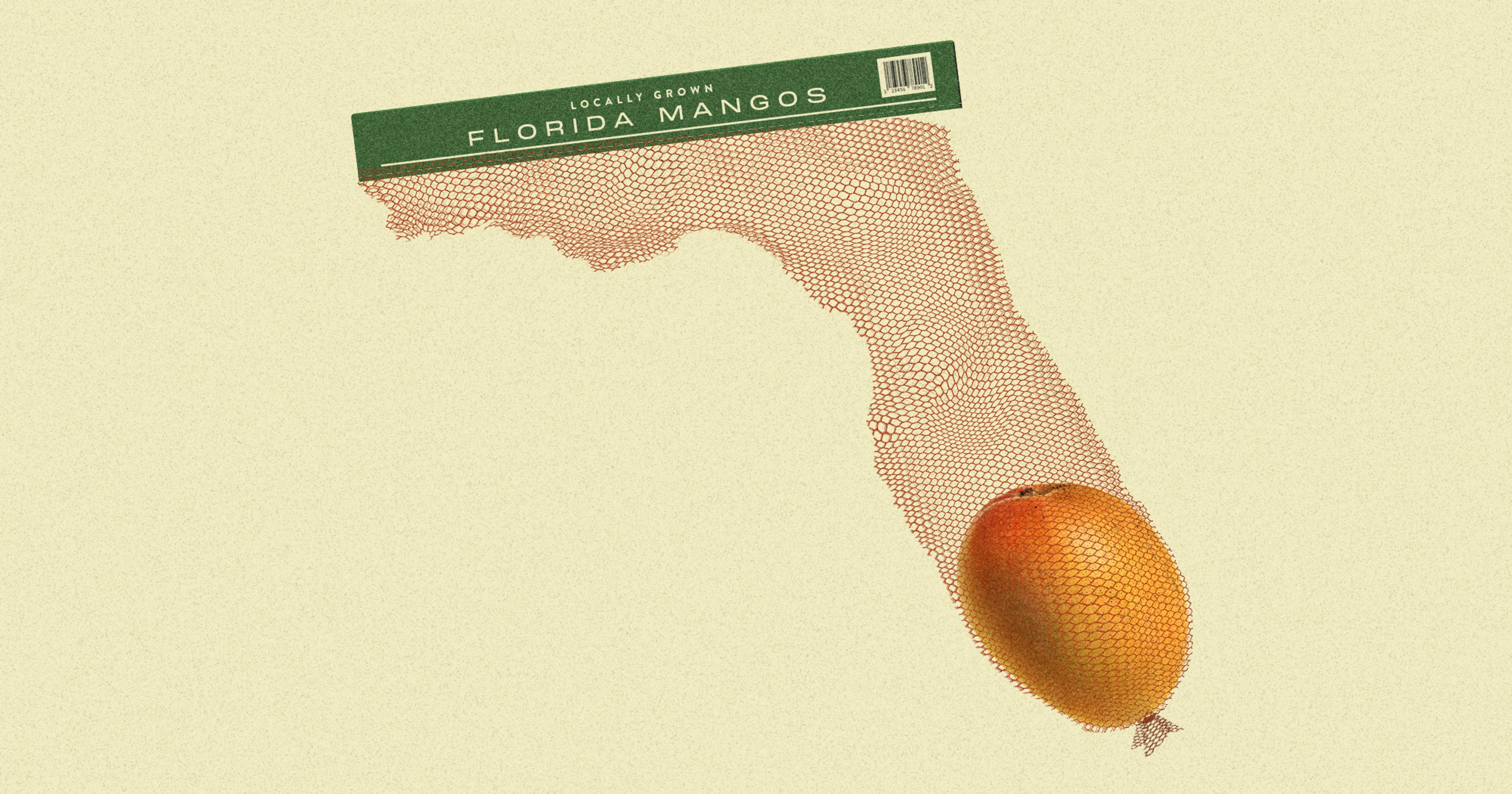

Historically, southern Utah’s agricultural landscape was dominated by alfalfa and other forage crops, essential to the region’s livestock-based economy but notoriously water-intensive. These crops thrived for decades, but as water scarcity has become an increasingly urgent issue, they are less viable in the long term.

Replacing alfalfa fields with vineyards represents a strategic rethinking of the region’s agricultural identity. Grapevines, once established, are far more drought-tolerant, requiring only a fraction of the water used by forage crops. By investing in wine, growers not only tap into a higher-value product but also embrace a sustainable solution for farming in one of the nation’s driest climates. This transition reflects a shift in priorities — toward crops that are both economically resilient and better suited to the environmental challenges of the future.

Ongoing research explores drought-resistant rootstocks, new pruning techniques, and experimental varietals from similarly arid regions, potentially from parts of Portugal or southern Italy, where climate conditions mirror Utah’s. Early climate modeling suggests that as global temperatures shift, more winemaking areas may resemble what Utah faces today. This positions the region as a laboratory for future-proof viticulture.

“The industry is growing fast,” McCombs said. “We’re selling more wine than we can grow, and there’s pressure to expand.”

By merging historical knowledge with scientific precision, selecting grapes that align with the climate, and leveraging every available resource — from university research to ground cover strategies — winegrowers in arid environments can secure their future. As climate patterns shift and water become ever more precious, the lessons from Utah’s wine country may guide other producers seeking to turn inhospitable landscapes into vineyards of possibility.

“I have so many people that walk out the door and go, ‘Hey, thank you for doing this,‘” Jackson said.