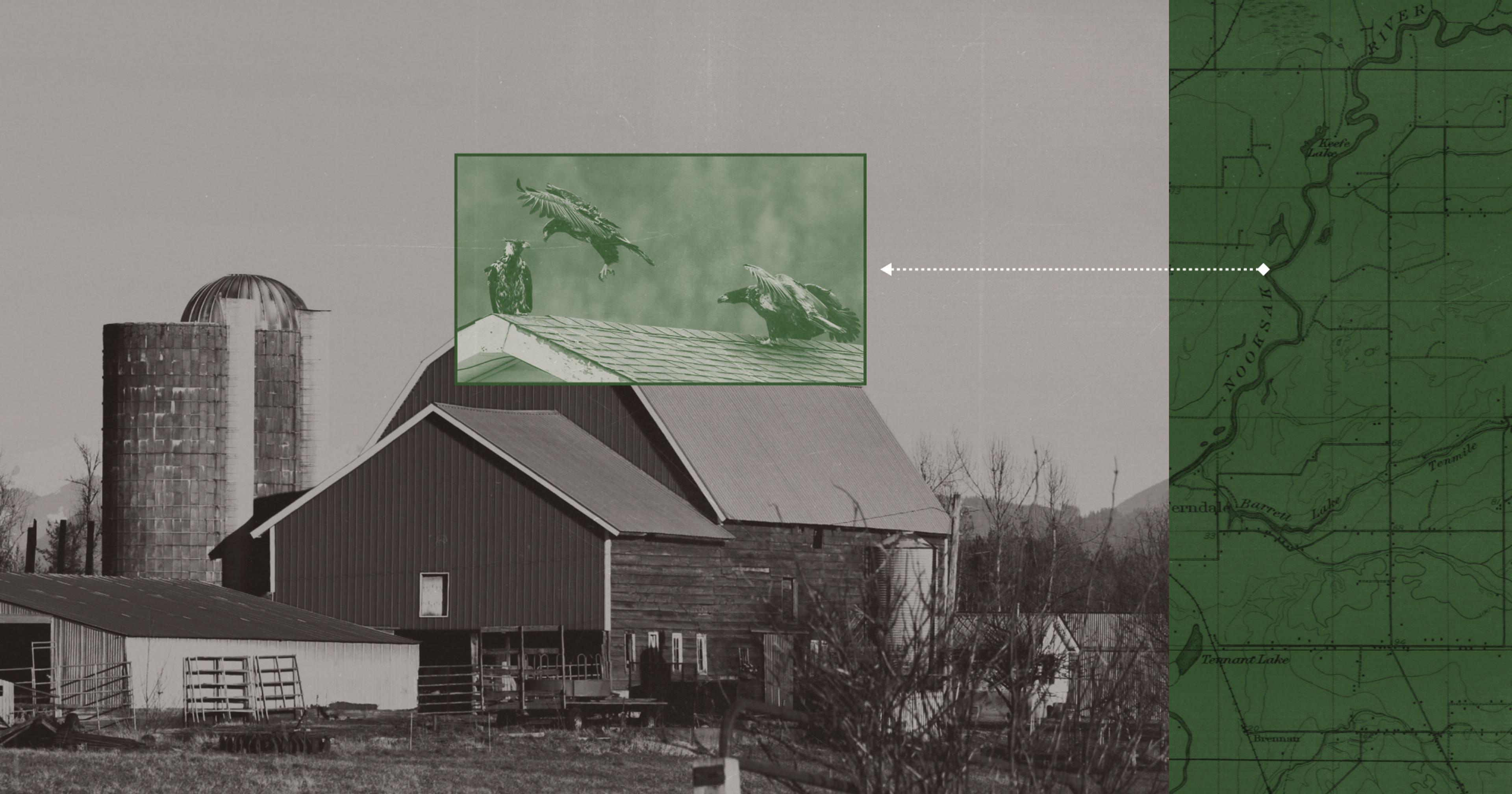

Farmers may want to preserve wild birds near their farms, but buyers’ fears of foodborne illness — and subsequent lawsuits — can make it tough.

In late August of 2008, an Alaska farm harvested fresh peas while sandhill cranes strutted down the rows, gleaning leftover peas and foraging for insects. The birds were regular visitors from the Palmer Hay Flats wildlife refuge, about 10 miles away, where 20,000 cranes congregate each summer.

Unbeknownst to the farmer, these stately birds left droppings that infected the peas with campylobacter jejuni, a bacterial illness that infects about 2.4 million people each year. After this batch of peas hit the market, close to 100 people fell ill and five were hospitalized.

As alarming as it was, this situation in Alaska is the only documented domestic incident of foodborne illness conclusively linked to wild birds through lab testing. Yet birds are often associated with food poisoning outbreaks in produce, leading buyers to make stringent demands and farmers to destroy wild bird habitats.

Where It Began

Most experts agree that popular fears about foodborne pathogens in produce started with an infamous 2006 spinach E. coli outbreak which caused 104 hospitalizations and 3 deaths. This outbreak was a major hit for food buyers. They dealt with financial losses from recalls, lawsuits, and plummeting spinach sales.

Facing economic losses and increased public scrutiny, food companies felt the pressure to make food safer. This pressure led buyers to institute new food safety practices including the removal of wildlife habitat on and around farms. While the 2006 outbreak was ultimately linked to wild hogs and cattle, buyers remained concerned about birds and other unrelated wildlife. They passed these fears down to their suppliers.

“There’s been incredible pressure on growers to do everything that they can to keep wildlife out of the farming environment in California.”

Daniel Karp, associate professor of wildlife, fish, and conservation biology at University of California, Davis, said that, “Since [the initial outbreak], there’s been incredible pressure on growers to do everything that they can to keep wildlife out of the farming environment in California. And then that’s kind of spread to other places throughout the United States as well.”

Over the last couple of decades, farmers have poured copper sulfates in the water, put out snap-traps and anticoagulant rodenticides, removed hedgerows, and made every effort to convince buyers their produce will not be tainted by local fauna.

While some farmers may not agree with these practices, continued food safety concerns among farmers and buyers have kept them alive. A study of the Salinas Valley (where the majority of U.S. salad greens are grown during warmer months) found that “over a 5-year period following [the 2006 spinach outbreak] 13.3% of remaining riparian habitat was eliminated or degraded.”

Testing the Fears

During the 2024 summer growing season, a team of researchers from UC Davis spent hours following bluebirds, turkeys, California quail, and other wild birds around the campus farm and nearby Putah Creek, dutifully collecting fecal samples. Their goal? To measure E. coli survival in droppings on lettuce, soil, and plastic mulch to determine how birds and their poop can affect food safety on farms.

At the end of the study, the team surveyed droppings from nearly 10,000 birds across 29 lettuce farms on California’s Central Coast. The team found that E. coli survival rapidly declines in bird feces, particularly those smaller than a quarter from songbirds and other smaller specimens. While they noted that E. coli lives longer on lettuce than soil or plastic mulch, likely due to the moist microclimate of lettuce, about 90% of all surveyed droppings were on the soil.

Their findings showed that birds on farms pose a relatively small food safety risk. They estimate that if growers ignored small bird feces on the soil, California lettuce farms following a no-harvest buffer around feces would be able to decrease the affected area from 10.3 to 2.7 percent. It also means that farmers could preserve habitat and even erect nest boxes to attract small, insect-eating songbirds to help with pest control — without compromising food safety.

John McKeon, who has been working on farms in the Salinas Valley for the last 25 years, shared a similar outlook. He’s noticed that for wildlife, there’s “a very high risk assumption” but that often the incident rate is actually really low, especially with wild birds.

“Pathogenic E. coli and salmonella are vanishingly rare in wild, farmland birds. And we now know E. coli tends to die off quickly in most bird poop.”

McKeon is currently working as the director of organic integrity and compliance at Taylor Farms, a massive agricultural operation that partners with other farms to produce about one in three salads in North America. Recently, Taylor Farms found that one of their 10-acre fields of romaine lettuce had accumulated significant bird feces.

Current safety recommendations include a “no-harvest zone” around bird poop including any crop that has been directly contaminated or could be by soil splash. The exact size of the zone depends on the crop type, number of droppings, and the size of droppings but it’s often around a 3-foot radius. Based on these guidelines and their own safety protocols, Taylor took this field off the commercial list, and decided to use it to further study the risk posed by wild birds.

They sampled bird poops throughout the field and tested for common foodborne bacteria. McKeon said, “Our incident rate was super-low, like no detection to only a few.” Then they had a harvest crew come through and run the lettuce through a rig before testing again, to “see what kind of detection we saw on that rig in terms of transference or cross-contamination potential, and again, the incident rate was really low.”

Don’t Blame the Habitat

Losing 10 acres of lettuce to wild bird poop is a financial loss for any farm, but Karp’s team has found that attempting to remove wild bird habitat may unnecessarily amplify this issue. Their work supports these conclusions. “Pathogenic E. coli and salmonella are vanishingly rare in wild, farmland birds,” he said. “And we now know E. coli tends to die off quickly in most bird poop.”

One of the team’s previous projects surveyed 20 strawberry farms on California’s Central Coast, a region that produces 43% of the nation’s strawberries. They found that removal of neighboring wildlife habitat had a negative impact on the farm.

“Our results indicate that strawberry farmers are better off with natural habitat around their farms than without it,” said lead author Elissa Olimpi, a postdoctoral researcher in Karp’s lab. The team found that removing natural habitat can increase crop damage costs by 76 percent. Conversely, adding habitat can reduce costs by 23 percent.

Karp explained that removing nearby habitat changes the way birds interact with the landscape and affects the type of birds on the farm. With less habitat available, more birds visit the farm. Large monoculture plantings that lack wild spaces also encourage more of the larger invasive species rather than native, insect-eating songbirds that benefit farmers. While many advocate for the ag benefits of birds for your farm — pest control is frequently invoked — Karp said he wishes we could reframe the way we think about them. Even on an intensive farm with no habitat around, you will still have birds. He encourages farmers not to think of birds as good or bad: “It’s like, what are you doing and how does that affect the birds and how does that affect the outcomes you want?”

In a 2022 study, Karp’s team examined the types of birds visiting farms and the pathogens they carry. They found that pathogens were most often found in birds associated with cattle feedlots, not the songbirds eating pests in a produce field. Karp said, “Our data suggests that some of the pest-eating birds that can really benefit crop production may not be so risky from a food-safety perspective.”

Changing the Conversation

Organizations like the Wild Farm Alliance (WFA) are trying to help farmers seize that benefit while protecting birds. They teach farmers how to support beneficial birds on their farms as a form of retro pest control.

Federal and state programs that regulate food safety on farms also seem to side with wildlife.

The USDA recommends against the removal of avian and other wildlife habitat and has implemented several programs designed to support wildlife on farms, including the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), and Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW).

Today, the vast majority of leafy greens growers in the Salinas Valley, including Taylor Farms, are members of the California Leafy Green Products Handler Marketing Agreement (LGMA). This program is a voluntary certification program for farmers that was created by the farming community in response to the 2006 outbreak. While joining is optional, membership requires farmers to verify compliance with food safety practices — more than 90% of U.S. leafy greens come from LGMA members.

When I reached out to them, leadership at LGMA noted they are first and foremost a food safety organization. However, communications director April Ward said that they do support wildlife co-management, which is “all about balancing food safety risk and conservation efforts.”

“We could go to the buyers and be like, you know, this is not benefiting anyone. It’s likely not making things more food safe.“

Like the USDA, they don’t recommend bird habitat removal. Instead, they recommend steps like “preventive barriers and increased monitoring” in specific situations along riparian areas.

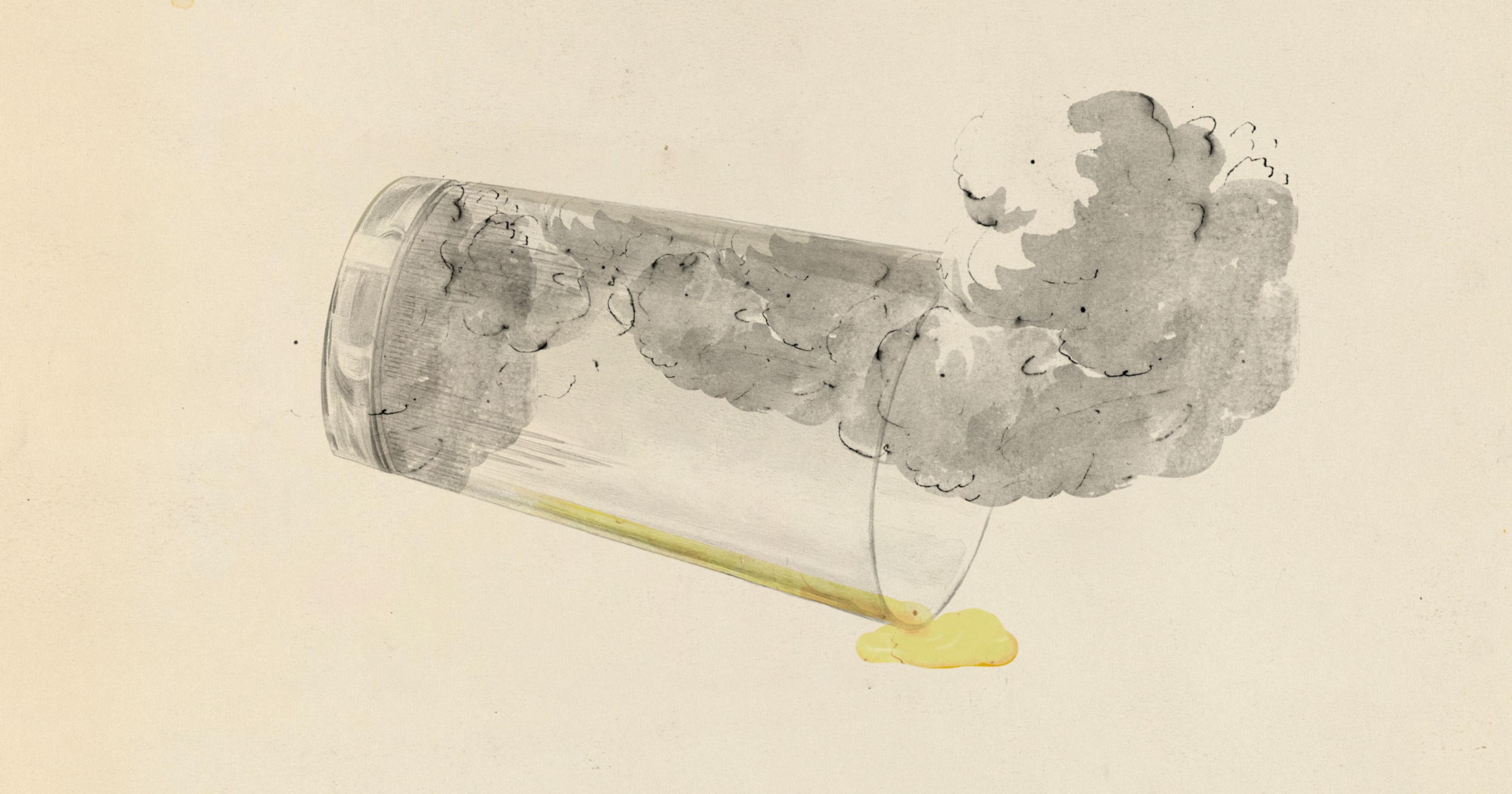

McKeon said that it again comes down to controlling the perceived risk versus the actual risk. He said, “You have customers that come out on a farm that may have never been on a farm and their sense of risk is different than yours.”

While farmers like McKeon may agree with Karp, the real challenge is getting buyers to the table. The team at UC Davis, along with other scientists and nonprofits, have done outreach events, testified before water control boards, and talked to farmers, but nothing will change if they can’t reach the buyers.

Karp hopes soon they can get farmers and academics together to form a coalition, “We could then go to the buyers and be like, you know, this is not benefiting anyone. It’s likely not making things more food safe. It’s costly from an environmental perspective.”