Kansas growers already face the periodic loss of irrigation. With climate change that risk could spread across the Midwest — and become permanent.

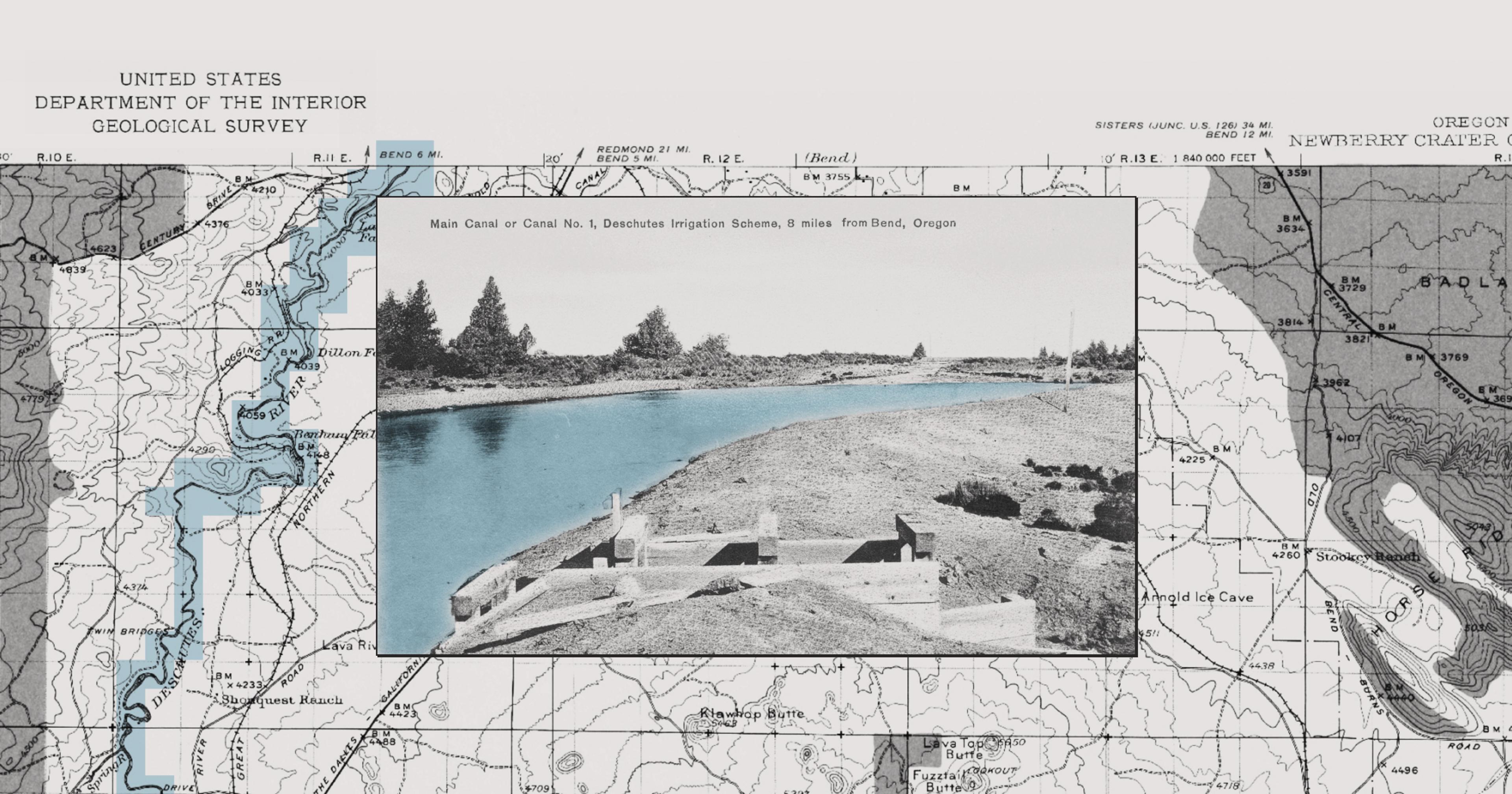

Dwane Roth left the army in the late ‘80s to be the fourth generation to farm row crops in West Kansas. Back then there was plenty of water. Wells across the 6000 acres his family owned or leased extracted 1000 gallons a minute from the Ogallala Aquifer — a hallmark of abundance.

But the supply dwindled. Over the decades well yields fell to 800 gallons a minute, then 700. It was still enough to irrigate but slowing water was a disturbing pattern. Then in the mid-2010s, the decline seemed to intensify.

“A lot of these wells don’t have the capacity they had in 2015,” much less a generation ago, Roth said.

It’s a tipping point, one that could mean an increasing number of West Kansas producers can’t get enough groundwater and become increasingly vulnerable to drought. Without conservation changes, the same will be true for other communities across the plains that sit on dangerously thin water.

Today well yields are lower — with the worst at Roth’s operation barely scraping by at 200 gallons per minute. He and his nephews were able to adjust, reducing all wells to far below their capacity. But some of their neighbors fared worse, forced in the last 10 years to stop irrigating altogether and revert to dryland crops.

New research published in Nature Water combined 30 years of water data with corn and soybean yield data to confirm the phenomenon that Roth and his fellow growers are experiencing: Parts of High Plains Aquifer, including the well-known Ogallala aquifer, have a point of no return — some farms and communities have already crossed it — and the damages that ensue can come with little warning.

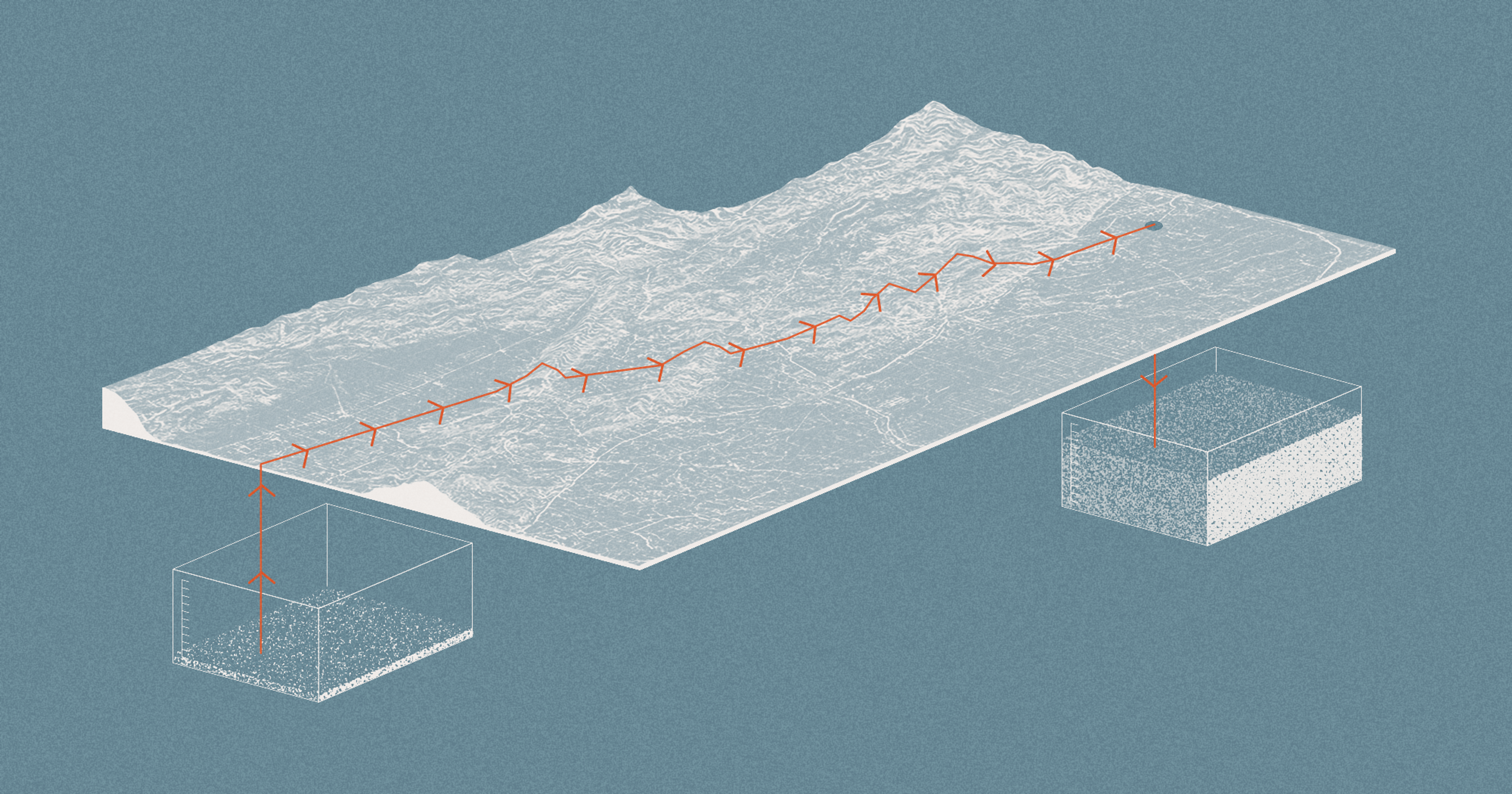

According to the research, when the aquifer first begins to thin the impact on yield is negligible. Just like in Roth’s case, well yields — the rate at which a well can pump water — wane from abundant to plentiful to enough, with little effect on crop yield. But as the aquifer is drawn further and further down, it becomes too thin. Once the water drops beneath a threshold, production challenges and losses start to escalate. Even as the aquifer appears to have plenty left to give, it becomes increasingly difficult or impossible to extract water at the rate that crops need it.

“At the point your wells tell you that you have a problem, you have very little time to intervene,” said study author Nicholas Brozović, director of policy at the Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska. And if you “wait until you’ve seen the negative effects, you’ve waited too long — too long to bring back the resource.”

To be clear, water scarcity is no secret in Kansas. Everyone in the region knows groundwater is in short supply — that current farmers could very well wipe out irrigation within a generation. It’s the tipping point that can still catch growers by surprise, Brozović said. After decades of irrigating the same way, a grower can find themselves unable to sustain their crops and facing permanent water loss.

When a producer has to turn off their pivot, the value of their land decreases by as much as half.

The trouble is that the effects of a thinning aquifer get progressively worse. Water use that worked for years can become impossible as the aquifer wanes too thin to sustain it. For example, water shortages and yield loss are more severe when the aquifer is depleted from 100 feet thick to 50 than from 200 feet to 150. According to the data, even if a producer uses groundwater at a consistent rate, water shortages and crop losses escalate. This is what makes already-thin areas on the aquifer so vulnerable.

Severe thinning can even ramp up in a single season. Katie Durham, manager of Western Kansas Groundwater Management District No. 1, has seen it happen. Wells pumping modest amounts of water start to rattle mid-season — the telltale sign that a well is pumping air.

A producer farming crops atop 40 feet of aquifer might estimate they have 40 years of irrigation left because the average West Kansas drawdown — or reduction in water level — is about one foot per year, according to Kansas State extension agent and water resource engineer Jason Aguilar. But the new analysis suggests producers can’t consistently drain the aquifer to zero — it will become too thin to meet their demands long before it’s emptied.

Already, thousands of irrigated acres across Kansas had to be converted to dryland rotation, which relies solely on soil moisture and rain. It’s a transition that tends to be an economic hit for the whole community.

Irrigation is the economic driver of western Kansas, according to Jim Butler, senior scientist in the Geohydrology Section of the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas. Where there is water underground, there tends to be economic flourishing and larger communities above ground, Aguilar added.

“At the point your wells tell you that you have a problem, you have very little time to intervene.”

But when a producer has to turn off their pivot, the value of their land decreases by as much as half. Dryland crops only bring a fraction of the profit producers get with water-intensive crops. And without irrigation, crop insurance costs skyrocket. Whole communities feel the change in cash flow, Aguilar said.

It’s a problem that will only be exacerbated by climate change. The thinning aquifer will leave irrigators more vulnerable to drought just as they need more water to combat rising temperatures and lengthening dry spells. “It’s a huge generational inequity,” Butler said.

The only option, based on the data, is for farmers to willingly restrict their water usage now, before they have to, Brozović said. But change can be slow.

Roth’s operation — which he transitioned to his nephews — is now in the 8% of U.S. farms that rely on special technologies to conserve water. Like many of his peers, he was initially skeptical. The first time a salesperson suggested a $1300 water probe to track soil moisture, Roth suggested the salesman shove it up his ass.

But in 2017, after hearing a lecture on the water crisis and with the help of his landlord, he enrolled in a water conservation program that gave him a few probes for free. Within the first year, he’d saved the equivalent of $60 per acre. Over five years he reduced water usage by 15%.

“There’s a window of opportunity we have, but that window is not going to be open much longer.”

“We never lost yield. I wouldn’t say it increased it, but we knew we could grow more with less,” he said. And if you’re talking profit, Roth said, reducing inputs is always a more reliable strategy than aiming for a bumper crop.

Others are right behind Roth. Since 2017, Western Kansas Water Management District No. One has cut water usage by 39%, Durham said. The thinning aquifer is a challenge, but producers are finding creative ways to reduce waste, she said. They must if they want to see their “sons and granddaughters have an opportunity to farm.”

Still, Roth works alongside many growers who continue to be frivolous with water, never turning off their pivots, pumping out of the aquifer even during abundant rain, he said. “Socially that’s unacceptable, but it’s not illegal.”

The trouble is not limited to Kansas, experts say. There are thin spots on the aquifer all across the plains, particularly in states south of Nebraska, at risk of the same water crisis. If those regions don’t take steps to prolong the life of the aquifer they’ll also lose the ability to irrigate.

“It’s not all doom and gloom,” Butler at the Kansas Geological Survey said. “There’s a window of opportunity we have, but that window is not going to be open much longer.”