The Silicon Ranch solar company has plans to install droves of sheep on sites across the country. Do the ecological and community benefits outweigh the methane output?

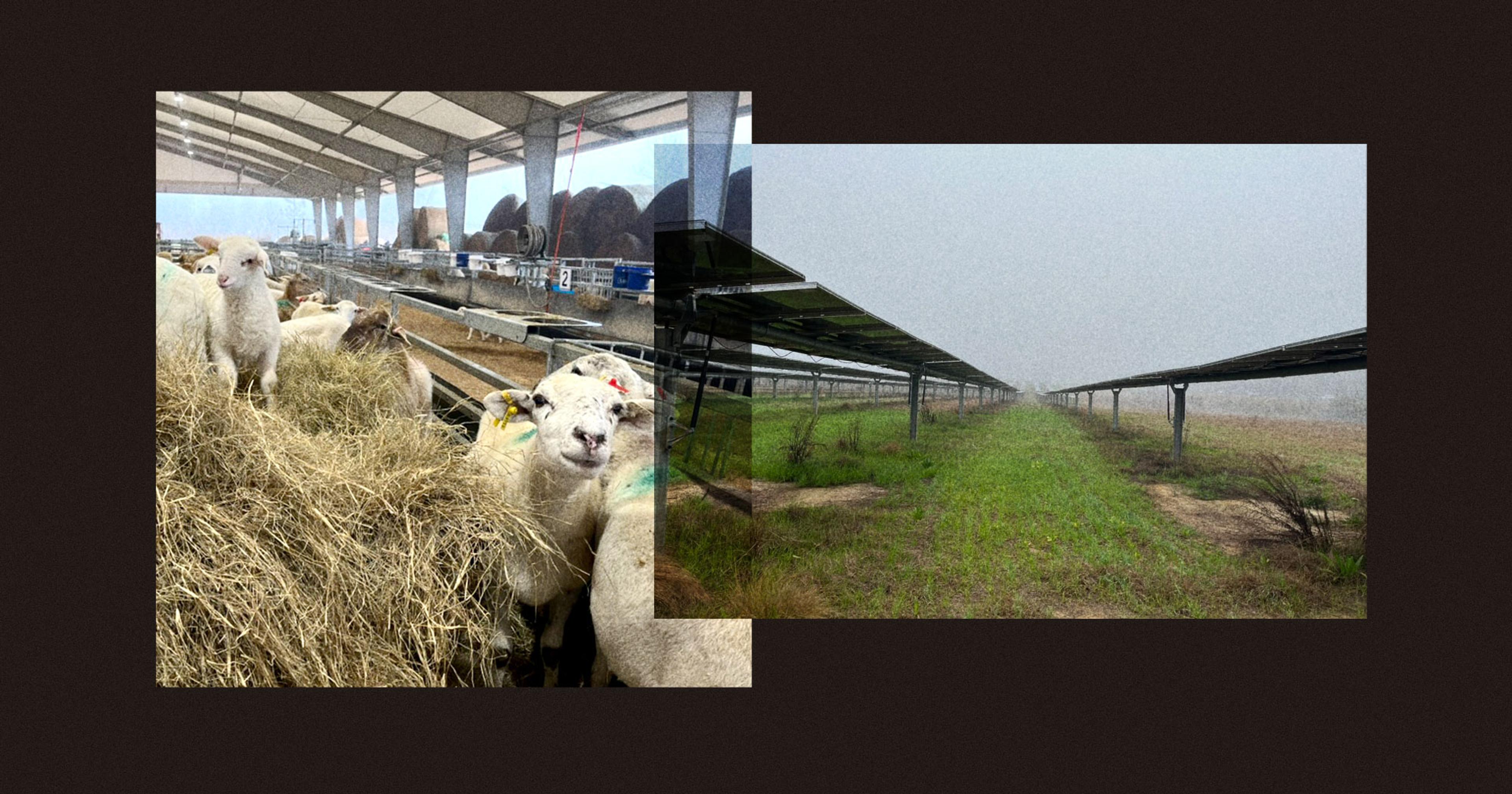

Rain is misting gently over some muddy, hawk-patrolled fields in Elko, Georgia, a sleepy town 117 miles south of Atlanta. Under the roof of a large sheep shed, though, pandemonium reigns. As their mothers poke their muzzles out of their pens to nibble snacks, dozens of curly-haired Katahdin lambs have seized the chance to wriggle out and are now boinging up and down the shed’s pathways.

The adorable chaos belies the more serious business afoot (a-hoof?) here. These lambs and ewes, about 800 sheep in all, belong to Silicon Ranch, a green energy company that combines solar power generation with agriculture, known as agrivoltaics, in all its installations. Agrivoltaics keeps land in food production — livestock rearing, in-soil and greenhouse crop production, for example — instead of giving it over to less beneficial turfgrass to undergird solar panels. In a few weeks, the Elko flock will be set loose beneath 560 acres of such panels to rotationally graze a smorgasbord of cool-season ryegrass and clover and vetch. The sheep are key to managing the site without the gas-powered mowers and intensive watering needed to keep turf in shape; eventually, many of the males will become food for humans.

Experts agree that this kind of “stacked” use of dwindling prime fertile farmland supports a slew of improvements to ecosystems, community, and green energy supply. But do these plusses offset the environmental impacts of spreading more methane-belching livestock across the surface of our planet? That is a trickier question, and one that hasn’t been well-studied. It also, said Emily Bass, associate director of federal policy at the nonprofit Breakthrough Institute, “requires a complex accounting of whether this demand [for lamb] exists in the market already, or if it’s being constructed.”

Silicon Ranch is a 14-year-old utility-scale solar company that has over 180 agrivoltaic sites in 15 states — about one-third of all that exist across the country — mostly in the Southeast. These sites, plus a few in Canada, generate 5 gigawatts of power, enough to service 1 million homes.

What food can be grown under solar panels is highly dependent on location; there are agrivoltaic sites in the U.S. that are ideal for growing blueberries, or lettuces. Some Silicon Ranch sites are suitable only for pollinator habitat and prairie strips — food for bees and butterflies. Two of their sites are being developed for eventual cattle production, which is a challenge, since panels must be raised higher off the ground to accommodate these animals; on the plus side, the panels provide shade that can protect cows from heat stress. And 25 of their sites have sheep munching through them already.

Sheep production was once a mighty American agricultural force, with a historic peak of 51 million animals back in 1884; that number has been whittled to about 5 million head today. With too few available animals to stock their sheep-suitable sites, Silicon Ranch is on a mission to revive the industry. Increasing sheep numbers means improving the genetics of Katahdins. This breed is a cross with one that hails from the Caribbean (and is not common in chillier Mountain states where much U.S. sheep rearing now happens), and is susceptible to a deadly parasite called the barber pole worm. As for the market for lamb: Americans eat an average of one pound of it a year, versus 60 pounds of beef; much of U.S.-eaten lamb is imported, though, leaving a niche for domestic suppliers to fill.

Katahdin lambs preparing to graze under solar panels in Elko, Georgia

·Lela Nargi

Silicon Ranch talks a big game about the positive impacts of its practices. Chief commercial officer Matt Beasley is quick to point out that as owner (rather than lessee) of all the land it develops, the company maintains control over what happens to that land. And what it wants to happen is for that land to continue to store carbon, improve water cycling, support pollinators, and feed people, using regenerative farming guru Allan Savory’s metrics for holistic management and ecological outcomes.

It’s also invested in helping revitalize rural communities with jobs and municipal revenue. “We’ve hired over 8,500 Georgians over the last 10 years to install, operate, maintain, and care for our land and those projects generate over $250 million in tax revenues for the counties where they’re located,” Beasley said. “We want to be good neighbors.”

Trade publication Solar Power World chose Silicon Ranch as its Most Forward-Thinking Contractor in 2020 “because they were absolutely ahead of the curve when it came to solar site stewardship,” managing editor Kelsey Misbrener said. “Even five years ago, they were working to minimize site grading and tree removal.” (Deforestation for energy generation can be one consequential negative of solar adoption.)

Although the tide may be turning when it comes to public sentiment, Misbrener said that NIMBYism was a big impediment to getting more solar panels out on the American landscape. “Developers spend a lot of time at local city commission meetings dispelling false rumors … about solar projects harming communities,” she said. Which is one reason Brent Kim, faculty scientist at Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, thinks there are a lot of positives in the agrivoltaics model. Since there’s “an economic and ecological urgency to wean ourselves off of our dependency on fossil fuels,” seeing animals roaming under solar panels might “move the social perception needle toward people understanding that, oh, these can actually be a win-win for rural economies and the environment,” he said.

But the methane, though. It’s an issue Kim said bears consideration, since one meat sheep emits about 25 grams of this potent greenhouse gas a day, contributing to a severe exacerbation of climate change. (This is still less than a mature beef cow, though, which emits as much as 396 grams a day.)

Sheep excited for their new solar grazing

·Lela Nargi

There are livestock producers who push the idea that methane from grazing livestock can be offset by soil carbon sequestration in healthy grasslands. “The problem with this kind of framing is that soil carbon sequestration itself has serious limitations, because once soil reaches kind of a carbon equilibrium, it can’t sequester anymore,” said Bass, and that potential varies by things like region and management practices. “So what happens when [livestock] continue to be grazed on these lands? It’s going to take complex emissions accounting to determine what that benefit is, if any.” She said even “optimistic” studies of carbon-for-methane offsets vary between 20 and 60 percent.

Adding to that complexity is the fact that methane and carbon are not equivalent when it comes to their global warming potential. Methane breaks down after 7 to 12 years in the atmosphere (as opposed to carbon, which lasts hundreds of years), but its ability to trap heat is up to 80 times greater than carbon dioxide’s. Said Kim, “There are studies that project that by the end of the century, driven predominantly by methane, agriculture alone could add another degree Celsius of warming to the planet. That’s really sobering.” Silicon Ranch is using a tool called a flux tower to monitor microbial gas exchange — that is, how much carbon is moving from land to atmosphere. Notably, that does not measure methane or its impacts.

Said Bass, when it comes to balancing the need for food with the need for more solar, agrivoltaics in some places “has real efficiency trade-offs that more research can help illuminate — Silicon Ranch even talks about how it costs more to raise panels to have livestock in these systems.” To better determine whether “the math pencils” on agrivoltaics systems, she’d like to see comparisons of land in solar alone versus agriculture alone versus the two together, as well as an economic analysis “to translate agricultural production and solar energy generation tradeoffs to impacts on profitability,” she said.

Kim, however, believes there’s already “enough evidence to say that agrivoltaics is among the potential viable options for expanding renewable energy, making more efficient use of agricultural land, [and] supporting regenerative grazers and rural economies,” he said. “It’s not a free pass to scale up ruminant animal production but if implemented well, there are a lot of wins.”

Paul West, a senior scientist at climate solution nonprofit Project Drawdown, agrees. “I think it’s important that we don’t oversell [agrivoltaics] as a climate solution,” he said. Nevertheless, “We need a stronger appreciation for multiple benefits — habitat and pollination and water and community electricity. When there’s too much emphasis on climate, those other benefits, which I think are greater, don’t have as much of the limelight and hence appreciation for their values.”