As the climate crisis worsens, flaws in our national safety net for farmers are becoming more pronounced.

This year, all the hopes Walt Hagood held for his Texas cotton farm were contained in dark seeds, so small they could spill through his fingers. In a normal spring, he would have planted them in soil readied by winter rains, where moisture would have seeped through the coats, softening and swelling the embryos. The primary roots would have stretched down, emerging from protective coverings. Expanding cells would have straightened, pulling free into a first glimpse of light above the surface. But a newly unfurled seed is fragile — too much moisture or not enough, too much heat or too little, and the miracle will end before it begins.

The winter in Lubbock County, Texas, was stubbornly dry. Months passed with essentially no precipitation. Then in late spring, it poured — tipping from one problem to another. Hagood, who has been farming for 44 years, was patient, waiting for the soil to dry until he thought the cotton would stand a chance. At first, it seemed to have worked. The seeds worked their magic; the stems toughened and grew. “We were in better shape than we thought we would be,” Hagood said.

But in July, a record-breaking heatwave began. For 46 days this summer, the mercury never dropped below 100 degrees in Lubbock County. Hagood watched weather forecasts closely as the soil baked. Most of his farm is not irrigated. “I was thinking, ‘Please rain, please rain.’” As the heat refused to break, his plants began to wither where they stood. “At that point, we started burning up,” Hagood said. “It just reached a point we knew it was over.”

It’s the second year in a row Hagood’s crop has failed, after an extended drought in 2022. “We’ve been through a lot of tough years,” he said glumly. “That’s why we talk so much about a safety net.” Like many commodity growers, Hagood buys insurance through the Federal Crop Insurance Program; though it won’t fully cover Hagood’s losses, it aims to help farmers survive this kind of season.

But as the climate crisis intensifies, more and more growers are finding themselves repeatedly in Hagood’s situation — jacking up the pricetag for taxpayers and straining the system in the process. A new report by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group found that extreme weather linked to warming triggered at least $118.7 billion in crop insurance payments in about two decades. Weather-related payouts have skyrocketed since 2001 — heat-related payments for losses like Hagood’s, for example, have grown by a factor of 10. The crop insurance program plays a huge role in federal agricultural policy. Yet despite mounting losses, its policies are failing to help farmers adapt to rapidly changing conditions.

Data Source: Environmental Working Group

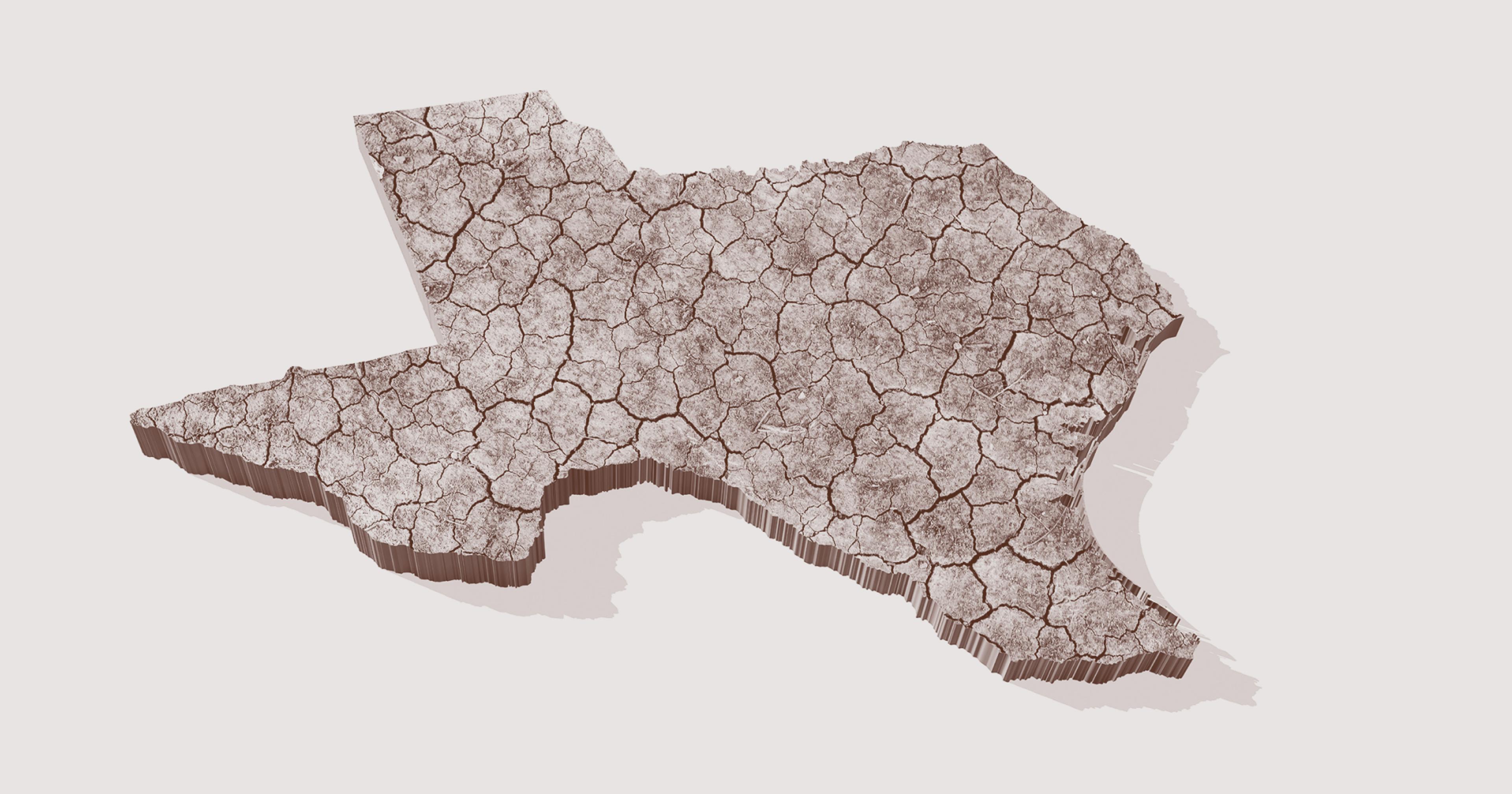

“We found there are hotspots, or areas with disproportionately high payouts,” said the report’s author, Anne Schechinger, Midwest director at EWG. Drought, the leading cause of weather-related loss, cost the crop insurance program $56.6 billion. The majority of these payments went to just 10 states in the central United States. Meanwhile heat-related losses — which increased nationally by 1,000 percent since 2001 — were scattered across the country in places like California and Kansas. Schechinger said that the geographic distribution shows the losses are correlated with specific weather changes, not just where agriculture tends to be practiced.

No matter which peril — heat, freeze, excess precipitation, drought, or hail — the Lone Star state was near the top of the list. “Texas is in a really unique position, where they’re being impacted by so many extreme weather conditions,” Schechinger said; the state’s crop insurance payouts totaled over $15 billion. “Asymmetric impacts,” a spokesperson for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) wrote in an emailed response to questions, are “one of the largest identified program risks to making sure the program operates properly for all.”

The EWG report joins a growing body of research sounding the alarm about how quickly agricultural losses are growing — and the increasing costs for taxpayers. “We are all paying for this,” Schechinger said. Unlike a private insurer, the federal program can’t go bankrupt, but its claims have spiked 500 percent in the last two decades. A 2021 study out of Stanford University found that “global warming has already contributed substantially to rising crop insurance losses in the U.S.” It looked at a slightly earlier period, from 1991 to 2017, and calculated that higher temperatures caused $27 billion in losses.

People may be more likely to accept risk if they don’t have to pay for the full consequences — driving more recklessly if they have car insurance, for example.

Even more troubling is research that suggests crop insurance programs may actually be making the problem worse by incentivizing farmers not to adapt. Counterintuitively, counties with higher crop insurance coverage actually see worse yield impacts from extreme heat, said Rod Rejesus, professor of agricultural economics at North Carolina State University.

Rejesus suggests something called a “moral hazard effect” may be part of the problem. The concept predicts that people may be more likely to accept risk if they don’t have to pay for the full consequences — driving more recklessly if they have car insurance, for example. Similarly, if farmers think their losses will be covered by crop insurance, they may be less likely to adopt costly practices to become more resilient to warming temperatures.

To qualify for the federal crop insurance program, farmers must comply with certain guidelines, for example, like following recommended planting dates, as well as federally approved standards called Good Farming Practices. These guidelines mean that even in regions with depleted groundwater, some growers can actually lose their insurance if they switch to relying on rain, rather than irrigation.

“We’re paying to keep farmers on this treadmill of planting crops that require irrigation,” Schechinger said. “And yet we’re still paying out a bunch of money in these counties for heat and drought [losses] — because there’s not any water there.” Another example of how farmers are discouraged from adapting is that they can also lose their insurance if they don’t follow strict USDA guidelines when they plant and remove cover crops.

“Cover crops can improve resilience to climate change, and also have the potential to sequester carbon,” Rejesus said. Yet perhaps because crop insurance requires strictly adhering to sometimes arduous guidelines, his research found that farmers in counties with higher crop insurance coverage were slightly less likely to use cover crops. As Civil Eats reported earlier this fall, for example, farmers hoping to plant multiple crops together, like growing wheat in grasslands — a practice that can help prevent erosion — are denied coverage.

“The business-as-usual of how people farm — it’s just not going to work with the extremes going forward.”

For small farmers, or those who grow diversified crops, it can be even more difficult to access insurance. The USDA offers insurance policies for these kinds of operations through the Whole Farm Revenue Policy, but they are less heavily subsidized, and many growers find they can’t afford the premiums.

Both sides of the political spectrum agree that current crop insurance policies aren’t meeting the program’s goals. The USDA predicts that 2023 farm income levels will drop by 22 percent, while expenses continue to rise. Hagood doesn’t blame climate change — “I don’t want anything that I say to come across as political, as much as just practical,” he said.

But he’s also seen firsthand how expensive insurance premiums are, and has been stuck paying for uncovered losses, either because the policies were too expensive to purchase in the first place or because many claims don’t end up paying out in full. He sees the impacts just driving around Lubbock, where every year more growers retire or go out of business. “You can tell there’s a lot of stress and a lot of financial pressure,” Hagood said. “We have to find a way to reform crop insurance.”

Yet a deadlocked Congress did not manage to pass a new Farm Bill before the last one expired on September 30. The Inflation Reduction Act had designated around $20 billion for conservation programs that would pay to help farmers become more resilient, and Republicans are now lobbying to repurpose that funding to provide higher subsidies to commodities like corn and cotton.

Schechinger, on the other hand, thinks larger reforms to the program are needed, as agriculture grapples with the scale of challenges to come. As temperatures rise, the costs of crop failure will only continue to grow. Models predict that as soon as 2030, crop yield failures will be 4.5 times higher, while by mid-century, major staple crops like rice or wheat might be failing every other year. Farming conditions in the near future will look very different, she said.

“Can we keep growing the same crops in these areas, that frankly, are not going to have water in the next few decades?” she asked. “The business-as-usual of how people farm — it’s just not going to work with the extremes going forward.”