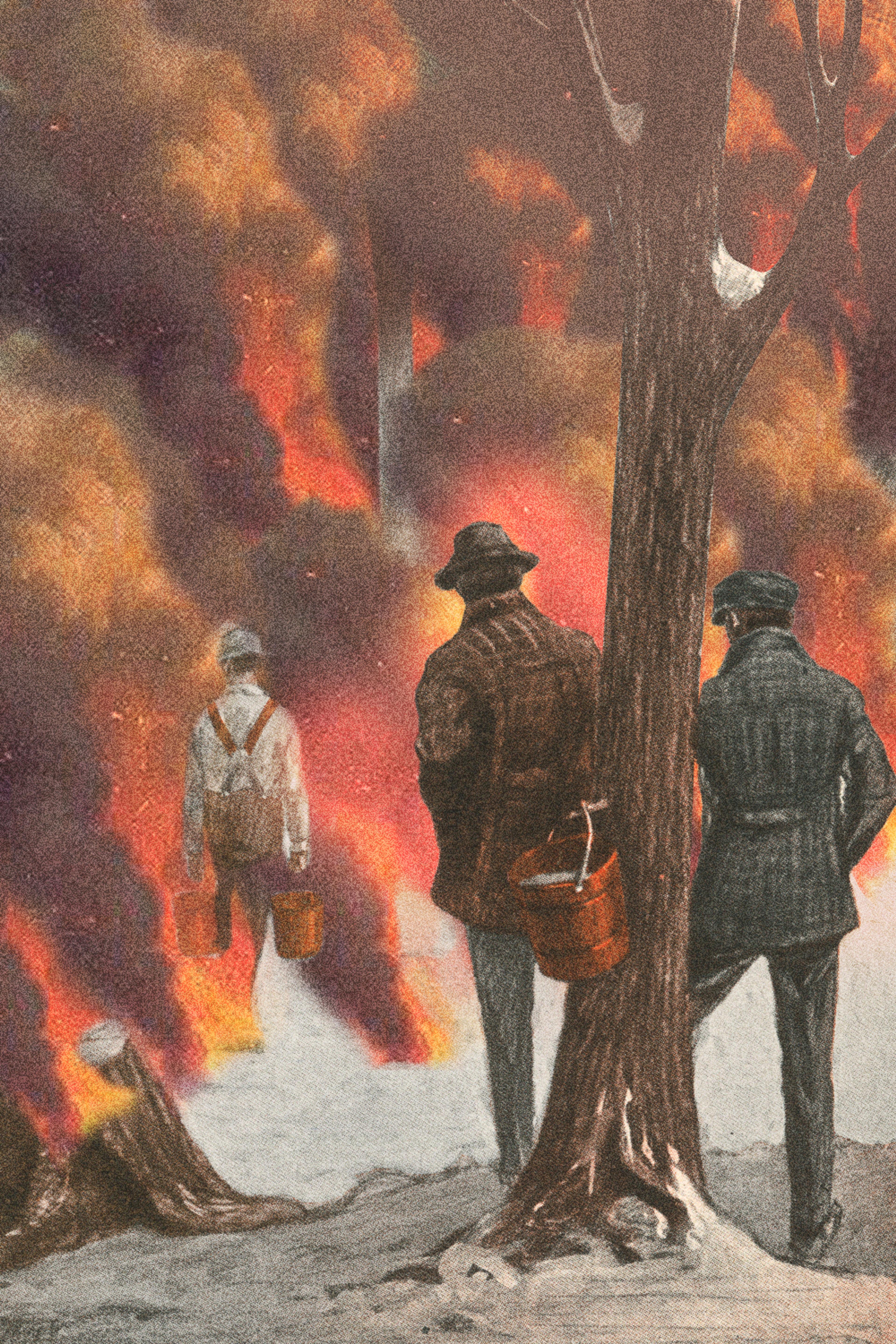

Maple sugaring has long been a precarious affair, at the whims of a host of variables. But after multiple winters of plummeting production, producers are starting to fear the worst.

Graphic by Adam Dixon

This time last year, Ojibway writer Staci Lola Drouillard made her way through the deep snow of northern Minnesota, approaching the oldest maple tree in her sugar bush to continue a family tradition. This tree, affectionately known as Old Man Maple in Ojibway, has seen generations of tappers from her family come and go. Drouillard and Old Man Maple are not unique in this.

A study last year on maple tappers from Appalachia to Montreal found that while maple tapping is becoming an increasingly large-scale industry, roughly half the tappers active today are the children or grandchildren of tappers. For the Indigenous communities that have grown up among the maples that familial link goes much further back and flavors the overall culture and lives of the community. For the Anishinaabe, the third month of the year, which falls roughly in March or April, marks the Maple Sugaring Moon when families would meet in the sugarbush to harvest what we now call maple syrup, sugar, and candy.

This year was different. Many small-scale tappers in the Midwest began tapping in January. In Grand Marais where Droulliard lives, “there was virtually no snow cover in the Superior Highlands along the North Shore of Lake Superior where the maple ridges are. We didn’t put snowshoes on once last winter — and that’s very unusual,” Drouillard said. “And because of unseasonably warm temperatures throughout last winter, the sap run was very unpredictable.”

Maple production is intricately tied to the weather around the tree. In general, to collect maple sap, temperatures need to be freezing at night but above freezing during the day. The snow that falls at this time of year has even been called sugar snow for its link to maple sugaring; without it, regional treats like syrup on snow are more or less out of the question.

This is why the shifting climate matters so much to the location of the sugar bush. Researcher Jay Wason at the University of Maine points out tree migration is often more complicated than people think and that many trees will not be able to swiftly migrate further north. For example, he said, “Sugar maple requires pretty rich soils with plenty of exchangeable calcium. We just don’t have that in many places … So we wouldn’t expect that species to move there easily. So, these soil constraints are definitely a factor.”

This soil differential is why maples and other hardwoods cannot simply be moved north. The maple leaf that dominates the Canadian flag does not even dominate the majority of Canada because the soil is simply not a good match for sugar maples; it becomes less habitable for maples the further north you go. Moreover, as any good tapper will tell you, a maple tree needs to be at least 30 years old before being considered. So while the climate may be warming, maple production cannot simply be shifted to different environments. Indeed, for many years the sugar bush offered northern farmers a buffer against bad weather crops by the extra income they brought in to local farms. Now, it seems that the maple tree is becoming the most climate-dependent producer on the farm.

“Sugar maple requires pretty rich soils with plenty of exchangeable calcium. We just don’t have that in many places.”

The climate also determines a whole host of variables related to adequate sap flow, quality, and overall production. This is because environmental factors directly impact the amount of sugar, metabolites, minerals, and other compounds in maple products. This has a direct link to the flavor, nutritional profile, and health attributes being captured in the sugaring. This includes the sugar content of the sap, with higher temperatures decreasing the amount of sugar. In terms of maple syrup, the less sugar, the more sap is needed to produce a gallon of syrup. Additionally, an overall increase in temperature has been seen to make tap holes less productive.

Harvard’s Joshua Rapp, a forest ecologist who studies maple production in the U.S. and Canada, points out that the issues surrounding maple tapping are not as simple as accounting for higher temperatures but also the unpredictability of the shifting seasons. He noted that, “One of the challenges with warmer winters is that collecting the most sap is not just a matter of tapping trees earlier than would be optimal in the past. As warm spells get more common throughout the winter, it becomes less predictable as to when the optimal time is to tap. Do you tap as soon as temperatures are in the right zone (say, in January), or later to catch the period when sap sugar content is higher and flows typically larger (in March) and risk having a short season because temperatures warm too fast?”

This new uncertainty is yet another challenge for those in an already unpredictable and complex market, prone to price fluctuations. At present, the maple industry in the United States is estimated to be worth over a 100 million dollars and is spread across the maple range, roughly from Appalachia to Minnesota. In 2018, for example, the value of production was 142 million U.S. dollars although it is the Canadians who produce the bulk of the world’s maple syrup with most production taking place in Quebec. In fact, it is a Canadian group, the Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers, that accounts for roughly 80% of the world’s maple production.

And like the maples themselves, the climatic change is being felt by maple producers across the entirety of the maple range, with 89% of producers having dealt with the negative impacts of climate change even before this unseasonably early sugaring. However, the work of scientists like Rapp suggests that some producers will be more impacted than others with the south more likely to see longer unseasonable warm periods.

In the long term, the maple range may shrink with production clustered around the areas that can provide the needed freeze thaw effect needed for a sugaring to occur. These sites are almost exclusively in the north and dependent on what is called lake effect snow which occurs when cold air moves across warmer water. As such, it is possible that maple sugaring could become clustered around the Great Lakes and parts of northern New England and eastern Canada.

“As warm spells get more common throughout the winter, it becomes less predictable as to when the optimal time is to tap.”

If that happens it is not only the production capacity of maple products that will be lost. It is also the traditions that surround the maple sugaring. The family gatherings that will not be had in the sugar bush. The pancake socials that will change. The tapping skills that will not be handed down. The unique relationship between the trees and the tappers that will be damaged or lost.

That, of course, is one future. It seems to be the most likely one. Already the world’s only maple reserve fell to a 16-year low. Yet forest-based agricultural systems remain under-researched compared to other agricultural methods — there is much to be studied. And importantly, the uncertain sugaring seasons of today, as eerie as they have been for producers, offer a heads-up that allows for the adoption of large and small-scale adaptive strategies, e.g., new production methods like reverse osmosis or very old methods like selective harvesting. Maple production also has one huge advantage over traditional agricultural products: Products can be reserved for a more profitable season or a more difficult one. In that regard, tappers may be set for a more traditional season in the upcoming year as La Niña promises to deliver a snowy winter along the maple range.

This new uncertainty has also sparked an interest in marketing techniques such as the benefits of obtaining an organic certification. There has also been a diversification of products being marketed beyond the maple range. Maple sugar has been touted as a safer sugar for those with diabetes (something organizations like Diabetes Quebec dispute). Less controversially, maple sap is having its moment in the sun as maple water, a healthier alternative to sports drinks.

For Indigenous tappers like Drouillard, challenges like these are hardly the first to impact her family’s ties to the sugaring. As she noted, “My great-grandmother and my grandfather’s generation experienced forced assimilation, land loss, and diminished access to tribal harvest lands. And yet, they continued to go to sugar bush, fish for trout in Lake Superior, go wild ricing in early fall, and hunt game all year long.”

In the meantime, Old Man Maple is still there for small local tappers like Drouillard. He just wakes up a little earlier these days.