Collagen is a cheap and abundant meat industry byproduct — so why is the supply chain so challenging?

All throughout America, people wake up each morning and spread cow across their faces.

Most of them probably wouldn’t put their daily beauty routine in those terms. But the phrase would be an accurate, if flippant, way to describe applying collagen cream.

In the United States, the key ingredient in the popular cosmetic — as well as the countless collagen supplement powders, capsules, and liquids that promise plumper, smoother skin — is usually derived from byproducts of bovine agriculture like hides, bones, and tendons. (Other animal sources of collagen, primarily pork and fish, are more popular in Europe and Asia.)

Demand for collagen has recently exploded, said Leo Manning, director of sales and marketing for the North American branch of global manufacturer Nitta Gelatin. The U.S. collagen market grew by a consistent compound annual rate of about 15 percent over the past five years. Research firm Global Market Insights placed the world collagen market at about $4 billion in 2022 and predicts ongoing compound growth of roughly 8 percent through the coming decade, in line with Manning’s own projections.

Yet supplies of collagen derived from American agriculture, noted Manning, haven’t kept up with domestic consumption. He estimated that only about 30-40 percent of bovine collagen produced in the U.S. can be sourced from cattle raised in the country. The rest comes from South American or European animals, including nearly all collagen advertised as “grass-fed” or “pasture-raised.”

As the collagen boom continues, many people are looking for new ways to meet domestic demand closer to home. Whether by tapping underused parts of the cattle supply chain — or by developing processes that don’t rely on animals at all — they’re looking for their own piece of an attractive market.

Collagen is currently produced from what farmers call “the drop,” everything that’s left from an animal once it’s been harvested for meat. In cattle, the drop accounts for roughly half of a carcass’s total weight, and depending on market conditions, represents about 10-20% of its value.

Lee Schulz, an agricultural economist with Iowa State University, said the drop is critical for the business model of large meatpackers. Companies with centralized slaughterhouses like Tyson and JBS USA can collect huge numbers of cattle hides and turn a tidy profit selling them to collagen manufacturers like Nitta.

“They’re able to offset their costs for the animal and get higher values for all of these products,” Schulz said of the big meat processors. “It also allows them to keep meat prices lower, because they’re able to capture more value from that system.”

“A lot of collagen buyers want much larger volumes, truckloads at a time, and it would take us half a year to get there.”

Yet the majority of America’s slaughterhouses are much smaller. Of the 776 federally inspected facilities operating in 2022, 499 harvested less than 1,000 cattle, and another 185 harvested less than 10,000. Because they don’t generate the volume needed to access industrial-scale markets for collagen and other byproducts, Schulz explained, many of these facilities have trouble getting the full value of their drop.

Some of those processors, he added, even find the drop to be a liability due to the lack of smaller-scale buyers, paying for its disposal rather than selling it at profit. That drives down the prices processors can pay to the locally oriented farmers they service, in turn driving up the costs of local meat.

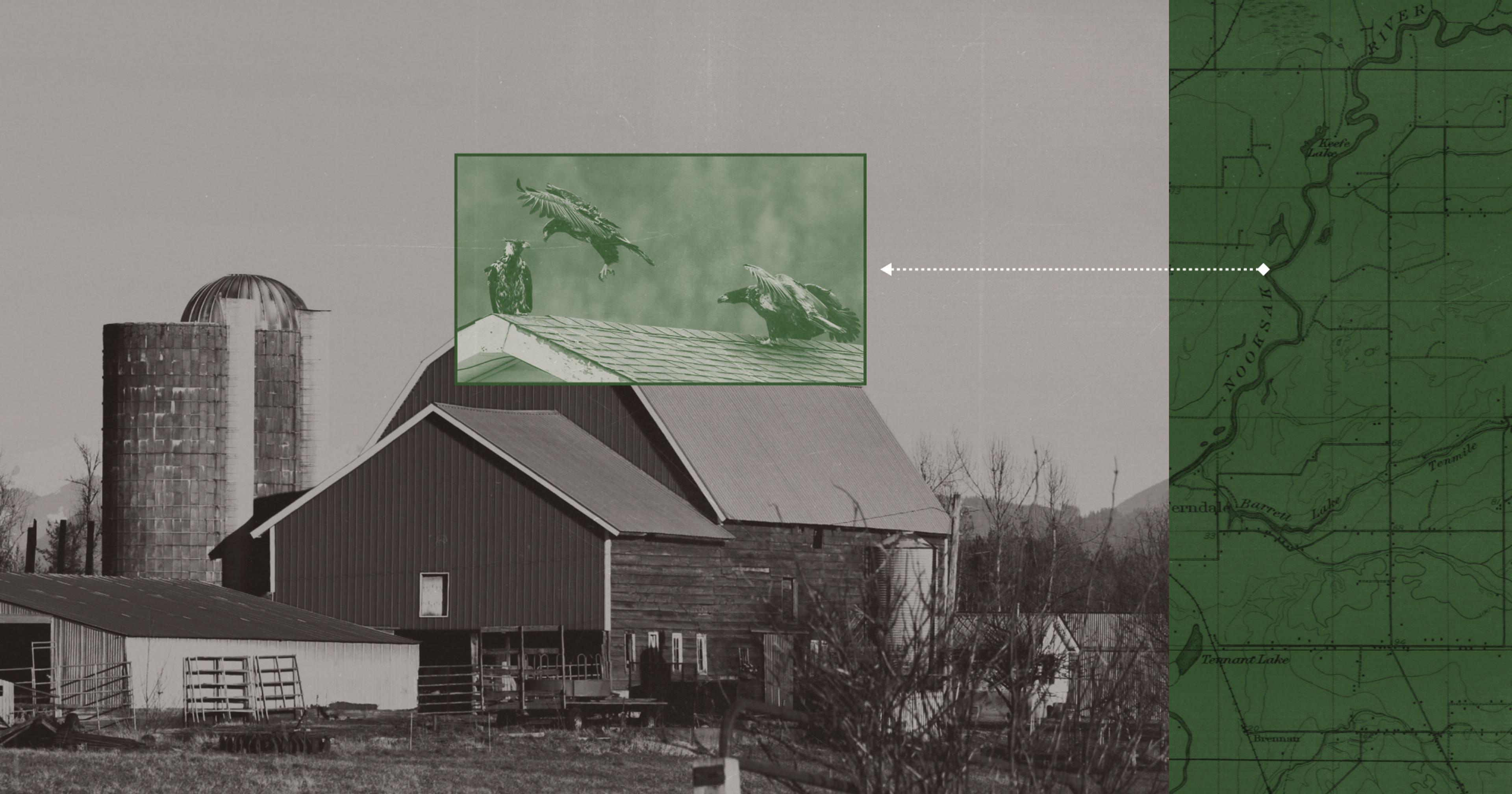

Hickory Nut Gap Meats, just southeast of Asheville, North Carolina, is a midsized producer struggling with its drop. The business farms beef, pork, and chicken on its own land, in addition to marketing pasture-raised meat from over 90 other farmers across the Southeast.

Ann Sitler, the company’s director of operations, said it can successfully offload many drop products — if they’re edible. Local restaurants want marrow bones and pig ears for applications like ramen broth; Hickory Nut Gap’s own “Vital Blend” ground beef incorporates hearts and livers. But about half of the drop still consists of products like cattle and pig hides, prime sources of collagen, that often go without buyers.

“A lot of [collagen buyers] want much larger volumes, truckloads at a time, and it would take us half a year to get there,” said Sitler. “Then you’d have to pay for the storage, and then it doesn’t make any sense, because you’re not getting enough to cover your costs.”

Some see greater potential in the drop of producers like Hickory Nut Gap. Mark Kleinschmit co-founded Minneapolis-based Other Half Processing with his brother, Jim, in an effort to bring small livestock farmers into the supply chain for hides and other byproducts. (Jim is also the project administrator of Growing GRASS, a five-year, $35 million effort focused on byproducts and funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program.)

“Collagen is super on-trend. If you can say that your product was produced via fermentation, which is more sustainable, that’s also super on-trend.”

Other Half verifies producers as using regenerative agricultural practices, aggregates byproducts from many of those farms to achieve the volume buyers want, then sells those materials at a premium — up to double the commodity price for cattle hides — to companies that want to make sustainability claims. The business has taken off with leather: Boot manufacturer Timberland and handbag maker Coach have both been consistent customers, Mark Kleinschmit said.

The brothers initially thought that collagen would be a good fit for the Other Half model, given the product’s market of health-conscious consumers and concerns over the sustainability of international sourcing. An investigation published by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in March, for example, found that many Brazilian cattle providing the raw material for collagen sold in the U.S., including the Nestlé-owned Vital Proteins brand sponsored by Jennifer Anniston, were raised on farms that had clear-cut tracts of Amazon rainforest and displaced Indigenous people.

But although demand definitely exists for regeneratively raised, U.S.-sourced collagen products, said Kleinschmit, the logistics of gathering enough raw material from distributed sources have so far proven impossible to work out.

“It’s a misfit in scale. What they’re used to working in and what’s interesting to them is just very different from what we’ve been able to come up with,” Kleinschmit said of collagen manufacturers.

Meanwhile, other businesses are turning from the slaughterhouse to the laboratory in their attempts to supply the collagen market. Rather than capturing more of the cattle industry’s byproducts, startups like Jellatech, Aleph Farms, and Geltor are raising millions of dollars to produce pure collagen from scratch.

New Jersey-based Modern Meadow uses genetically modified yeast that ferment plant-based sugars into a variety of proteins, including its trademarked Bio-Coll@gen. Jason O’Neill, Modern Meadow’s senior vice president and general manager of beauty and wellness, said the product is already in use by South Korean beauty brand AHC, and offerings from other brands are expected in January in partnership with the ingredient supplier Evonik.

A kilogram of lab-grown collagen costs tens of thousands of dollars, compared to about $12 per kilogram for bovine collagen.

“With beauty, the business is all about being on trend,” O’Neill said. “Collagen is super on-trend; if you can say that your product was produced via fermentation, which is more sustainable, that’s super on-trend. We see that driving demand.”

Lab-grown collagen makers still have a long road to travel before they could meaningfully displace existing sources of collagen in the market, especially in food and nutritional supplements. Modern Meadow’s current beauty product is based on human collagen and promotes the body’s own collagen production, but it doesn’t have the triple-helix molecular structure that gives animal collagen its stability.

O’Neill said the company has developed a way to replicate that structure in the lab but is still a ways out from commercial deployment. (He also acknowledged that it’s unclear if lab processes have a substantially lower carbon footprint than harvesting animal byproducts, although they generally need less water and land.)

Perhaps more importantly, the company’s production costs are orders of magnitude higher than animal-based manufacturers. A kilogram of Bio-Coll@gen costs tens of thousands of dollars, compared to about $12 per kilogram for bovine collagen. “We wash that down the drain every minute,” said Manning of Nitta Gelatin, about the limited amount of product firms like Modern Meadow are currently producing.

O’Neill nevertheless argued lab-grown collagen could represent 5-7 percent of the broader wellness market by the end of the decade. He pointed toward the history of hyaluronic acid, another popular skincare ingredient. Traditionally derived from rooster combs, it’s now largely produced by the biotech industry after 20 years of research and development drove down costs.

“I don’t see any of this ever wiping out animal-based collagen,” he said. “I think you’re just going to see a segmentation in the market where you’re giving consumers more options.”