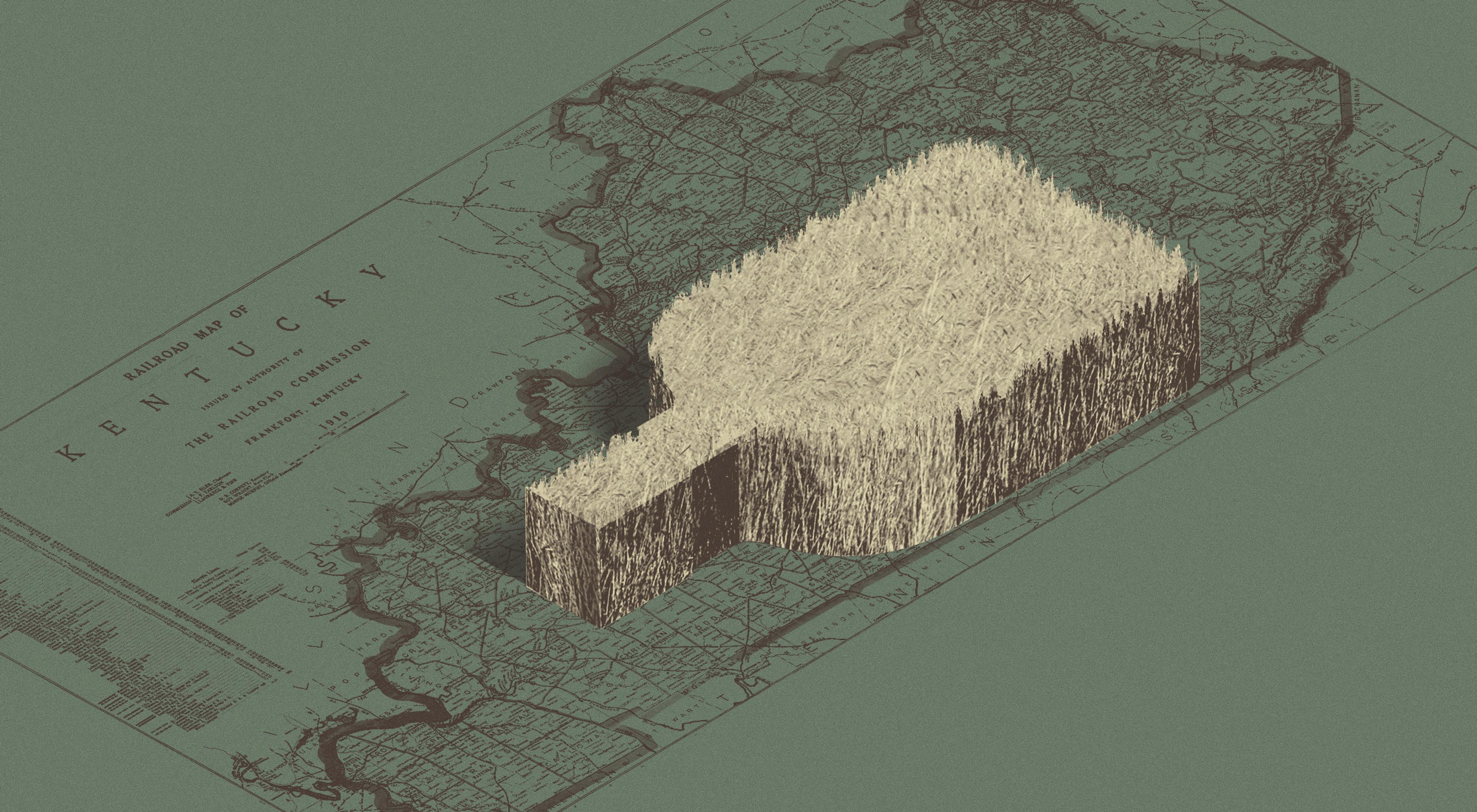

The Bluegrass State currently imports a key ingredient for its signature spirit. The bourbon industry wants to change that.

A glass of Woodford Reserve is among the crowning jewels of Kentucky. The official drink of the state’s most famous cultural export, the Kentucky Derby, the bourbon shines in the light like a clear amber gemstone. Each sip lingers as it presents a complex blend of flavors, from citrus and cocoa to caramel and spice.

Yet those who enjoy Woodford — or practically any bourbon made in the Bluegrass State — aren’t tasting the work of Kentuckians alone. While its water is drawn from limestone-filtered springs, and its corn from nearby farms, the ingredient that gives good bourbon its distinctive pepper and herbal notes is shipped in from thousands of miles away.

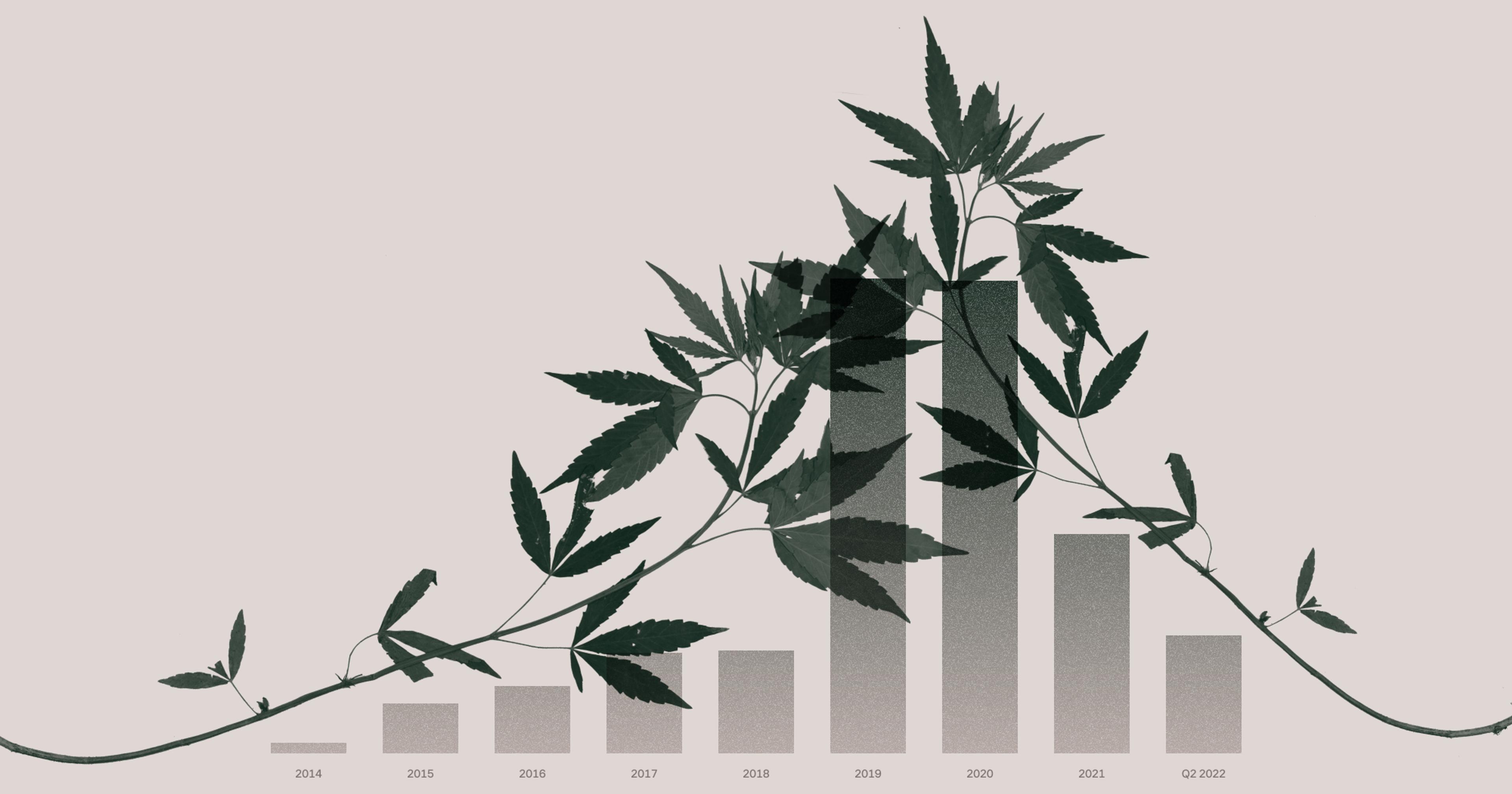

Rye makes up 18 percent of the grain (the technical term is mash bill) used in Woodford’s flagship bourbon; the percentage for other well-known bourbons ranges from 10 percent in Elijah Craig to 28 percent in Bulleit. Rye whiskey, another popular Kentucky spirit, legally must contain at least 51 percent.

Early in the state’s history, area farmers grew enough rye to supply its distilleries. But when Prohibition shuttered alcohol production in 1920, according to Woodford Master Distiller Elizabeth McCall, the market for local rye evaporated. In response, most Kentucky farmers shifted to a rotation of monocrop corn and soybeans — by the time distilleries reopened to pent-up demand in the 1930s, domestic rye production had all but disappeared. Distillers looked abroad, sourcing the grain from places like Germany, Poland, and Canada.

In the interests of sustainability, supply chain resilience, and good old-fashioned local pride, the bourbon industry now wants to bring rye back to Kentucky. Since 2017, Woodford Reserve has been partnering with nonprofits, farmers, and academics to explore the crop’s economic potential and develop varieties suitable for the region. In 2023, the collaborative launched a five-year, $1 million program that combines support for growers, plant breeding, and distillation research. And other distillers have already started to buy the resulting grain and release bottles where it plays a starring role.

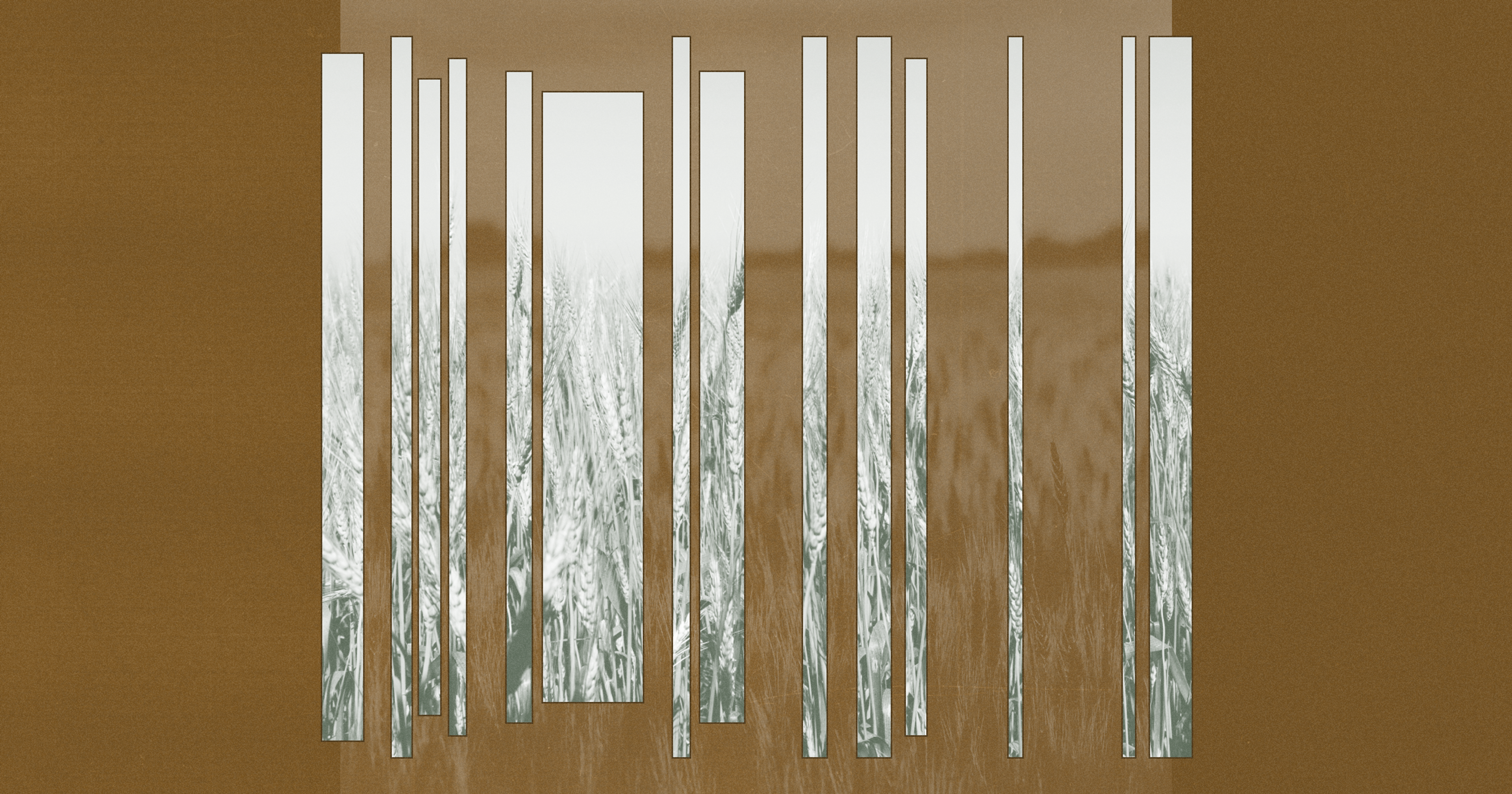

Those familiar with cover crops will note that rye is a common cool-season option for growers looking to suppress weeds, scavenge excess nitrogen, and prevent erosion. That’s true in Kentucky as well, notes farmer Sam Halcomb. Since 2009, his family has planted rye after the fall corn harvest on some of the roughly 9,000 acres they manage through Walnut Grove Farms near the state’s southwest border, preparing the soil to sow soybeans.

What’s new, Halcomb says, is letting that rye mature to harvest. Kentucky’s warm, humid climate isn’t optimal for the cold-tolerant plant, and with limited regional research on best management practices, area farmers knew their yields would be lower than in rye’s European heartland. Due to existing international supply chains, there’d be limited local demand for any product they could grow.

And unlike in Europe, where the grain is often sold as swine feed, America lacks an established market to absorb rye that doesn’t meet distillery quality standards. So Kentucky farmers generally terminate their rye crop early using herbicide or a mechanical roller-crimper, giving them a head start on soybean planting.

“There’s nobody going out knocking on doors in Kentucky saying, ‘Hey, do you have rye for sale?’”

“There’s nobody going out knocking on doors in Kentucky saying, ‘Hey, do you have rye for sale?’ Since nobody’s asking for it, nobody’s growing it [for grain],” Halcomb explained. “It’s kind of a vicious cycle.”

Policy choices have also made rye farming less attractive. Walnut Grove Farms has received funding from federal conservation programs for growing rye as a cover crop, Halcomb says, but it doesn’t qualify for that support when harvesting the grain for sale. And because commercial rye lacks a recent Kentucky history, crop insurers require growers to jump through extra hoops when seeking coverage and offer less generous terms.

In response to those economic headwinds, the rye project collaborative is giving Halcomb and three other Kentucky farmers a $5,000 annual stipend to grow 26 acres of rye each. Woodford then guarantees the purchase of all the grain from those acres at a premium compared to the commodity market.

“The program is intended to de-risk taking on a new crop,” said executive director Barbara Hurt of the Louisville-based nonprofit Dendrifund, which committed $500,000 and helps coordinate the project. “The farmers are putting in a lot of effort and in-kind value to the program, and we want to make sure it doesn’t hurt their bottom line.”

Another chunk of funding backs the work of David Van Sanford, professor of wheat breeding and genetics at the University of Kentucky. He and grad student Ela Szuleta evaluated nearly a thousand rye varieties from across the world, narrowing them down to about 40 that are most suitable for the state. Many originally hail from the Balkans, the European rye region with the closest latitude to Kentucky.

“The farmers are putting in a lot of effort and in-kind value to the program, and we want to make sure it doesn’t hurt their bottom line.”

With that genetic material as a starting point, Van Sanford hopes to breed an open-pollinated rye that matures quickly, thereby avoiding the worst of Kentucky’s heat and allowing farmers to plant their soybeans on schedule. He also aims to incorporate resistance to fusarium head blight, a fungus that can make rye toxic to consume, and a dwarfing gene to keep the plants from growing too tall and falling over in the field.

“I still feel like we’re at the fairly steep part of the learning curve,” Van Sanford admitted. But he’s encouraged by Kentucky’s history of wheat research, which has roughly doubled yields over the past four decades through improved varieties and management. Within the next five years, he says, it should become clear if similar improvements are possible for the state’s rye.

Meanwhile, McCall is hard at work evaluating Kentucky-grown rye for its distilling potential. Her team at Woodford is making small-batch whiskeys and serving them to a highly trained panel of judges, who taste for distinctions between rye varieties or grain grown in different parts of the state. She says the native product generally has a bolder character when it first comes off the still, with more floral, fruity, and spice notes, but that those differences tend to mellow with age.

Yet only a handful of boutique distilleries are currently selling whiskeys made with Kentucky rye. Examples include Monk’s Road Rye Whiskey by Log Still Distillery and the Kentucky Straight Rye Whiskey by Wilderness Trail. Bigger players are taking their time: Woodford only plans to release its first bottle with Kentucky rye as part of its premium “Master’s Collection” in a few years, while Heaven Hill will incorporate it through a limited-run “Grain to Glass” series.

McCall hopes that the locally grown grain will one day be much less of a novelty. “We’re committed to normalizing Kentucky rye, and hopefully mitigating the premium cost of it,” she said. “The dream is that it’s comparable to your standard rye that we’re getting now. And I think we’ll get there — it’ll take a long time, but I think we’ll get there.”