Much of the world debates GMOs purely in terms of human health and the environment. In Mexico, it’s also about cuisine, culture, and heritage.

In December 2020, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed a decree to gradually ban glyphosate, one of the world’s most common herbicides, and all genetically modified (GM) corn, by January 31, 2024. The Mexican government holds that glyphosate, widely used on GM crops which are engineered to be resistant to the herbicide, is harmful to human health. It was a bold move from the second-largest importer of U.S. corn, most of which is genetically modified, but it wasn’t until last November, with the deadline fast approaching, that the U.S. began to push back.

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack met with López Obrador to express “deep concerns” and threaten to file a formal complaint under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Mexico voiced concerns over GM corn’s impact on human health, a position the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative claimed was “not grounded in science” and threatened “to disrupt billions of dollars in bilateral agricultural trade.” Still, the Mexican president wasn’t backing down. But in February 2023, after enough pressure from U.S. agriculture officials, farmers, and the industry’s biggest lobbying groups, Mexico gave in.

López Obrador issued a new decree which eliminated the previous January 2024 deadline to ban GM corn for livestock feed (imports will still be banned for human consumption). Without a set date for the complete substitution of U.S. GM corn imports, the new rule simply says Mexican authorities will carry out “the gradual substitution” of GM feed. Still, the U.S. was not satisfied with this watered-down version of the decree and in March requested formal trade consultations. Negotiations failed in June, according to the U.S. Trade Representative’s office, and so, backed by Canada, the U.S. asked to open the USMCA’s dispute process against Mexico.

Mexico’s move to ban genetically modified corn is part of a decades-long fight to protect the country’s many varieties of native corn against the global agroindustry’s push toward GMOs. Mexican activists are celebrating the essence of the decree, less so its failure to set a concrete date on the ban. They are aware of the enormous pressure Mexico’s trade partners are exerting and intend to keep pushing back.

Corn is a staple of the Mexican diet and an integral part of its heritage, culture, and traditions. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) put corn on its Intangible Heritage of Humanity list for its role in Mexican culture and gastronomy. As such, corn is being defended from many different fronts. Along the same lines, the Mexican government is attempting to prove that glyphosate and GM corn are dangerous for human consumption and health, introducing alternative agricultural practices and herbicides that are sustainable and culturally appropriate.

The dispute over corn between the two countries is not only guided by economic principles but also with what corn fundamentally represents for the trade partners. “We weren’t satisfied with the new mandate because for us, corn for industrial use and livestock fodder is still corn for human consumption,” explained María Leticia López, director of the Asociación Nacional de Empresas Comercializadoras de Productores del Campo (ANEC), a national farmers’ organization. Though corn in the U.S. is mostly used for livestock production and industrial use, she continued, corn is not a commodity in Mexico. That’s the fundamental difference: “We eat corn and Mexico is obligated to preserve the health of its population.”

White corn makes up almost 87% of Mexico’s corn production, some 22 million tons a year, most of which is for human consumption. Mexicans eat on average around 432 pounds of white corn per year, largely in the form of tortillas. On the other hand, while the U.S. is the world’s largest producer and consumer of corn, less than 2% is for human consumption, according to the World Resources Institute.

“Mexico could make up for its deficit of yellow corn for industrial and fodder use but it won’t be easy or short-term.”

Mexico is home to about 60 native varieties of corn, a product which was domesticated through human selection in what is now south-central Mexico some 10,000 years ago. In pre-Hispanic times, Indigenous peoples worshiped maize as a deity and today, their descendants have preserved the respect for this sacred plant. Communities across Mexico hold celebrations and rituals around maize’s agricultural cycle: the selection of the seeds and the plot of land, the rituals asking for rain, the harvest of the first corn, and the final harvest.

“The free exchange of seeds has paved the way to so many varieties and it is an inalienable right of Indigenous peoples,” said Cristina Barros, a renowned researcher of Mexican traditional cuisine. “What transnational GM companies want to do is create a dependency on their seeds so that farmers have to buy them every season, plus their biotech package to grow the crop, at whatever price they want,” she said. “Indigenous peoples have a right to their heritage.”

Corn continues to be an intrinsic aspect of Mexican life, culture, and history. From its tamales and the different iterations of tortillas — sopes, tlacoyos, tostadas, gorditas, and totopos — to traditions like the Day of the Dead celebration, maíz is present.

“[The decree] is not about defending one type of corn over another,” said Barros. “It is about defending our millenary cultural traditions, our health, and ancestral forms of living.” Mexico’s move to ban GM corn is not based on a whim or the romanticization of the past, she said, but on the fact that Mexicans have domesticated corn, protecting its biodiversity and making it a main source of nourishment for centuries. As such, Mexico is self-sufficient in producing enough white corn for human consumption. It’s meeting Mexico’s many other corn needs that creates a problem.

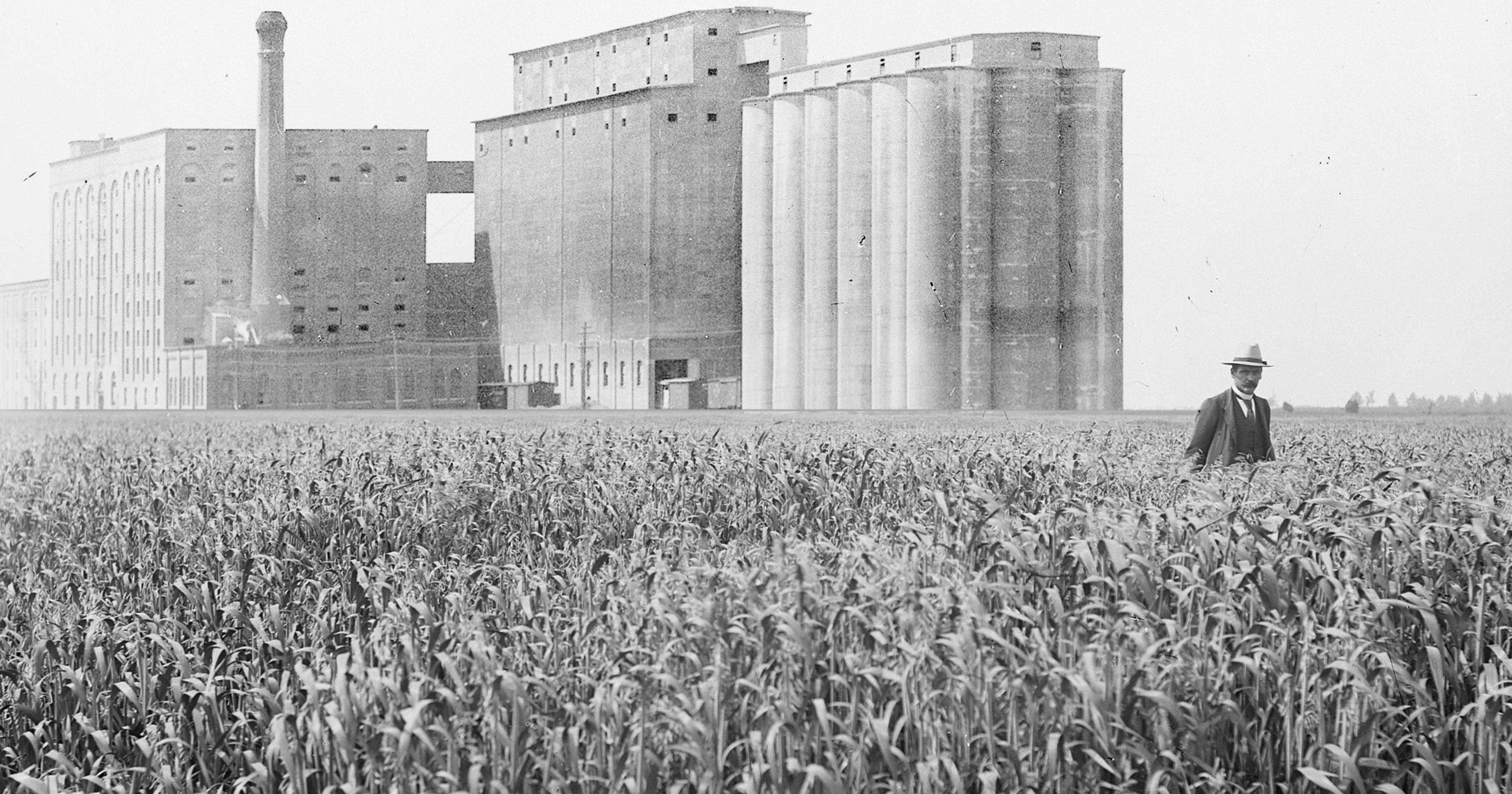

Since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the mid-1990s, Mexico’s agricultural sector has been undergoing significant changes. NAFTA essentially opened Mexico’s doors to low-cost U.S. corn producers which resulted in the 17 million metric tons of annual corn imports today. Even if Mexico had stood its ground against the pressure from its trade partners with the recent decree, the country is not yet able to make up for U.S. GM corn imports on its own.

“There are corn producers in the U.S. who are willing to change their GM corn for non-GM corn. We are fighting the same fight.”

“Mexico could make up for its deficit of yellow corn for industrial and fodder use but it won’t be easy or short-term,” said López. To start off, Mexico needs policies that promote the restoration of natural resources, she said. “We have to restore the damage and contamination of the soil, desertification, deforestation, lack of water, and more.” That implies an additional cost that producers shouldn’t absorb, she added. ANEC is leading efforts to do exactly that by teaching practices and new technologies to farmers so that they can regenerate their lands and grow crops more sustainably. A transition is feasible, said López, but it won’t come from a magic trick.

As it stands, the decree is just a piece of paper, explained Malin Jönsson, coordinator of Fundación Semillas de Vida, an organization that preserves maize’s biodiversity. It needs public policies to address issues of traceability, for example, to make sure that GM corn doesn’t end up in flour and tortillas. Traces of GM corn have been found in corn tortillas even though the planting of GM corn for commercial use is banned in Mexico. To prevent this from happening, in late June, López Obrador introduced a 50% tariff on white corn imports, which it imports in really small amounts, and on July 19, modified Mexico’s regulatory standards to ensure that tortilla makers only use non-GM white corn.

In 2001, researchers raised concerns over the contamination of GMOs on the genetic diversity of Mexico’s native crops. Native varieties such as bolita corn, used to make tlayudas, or cacahuacintle corn, used to prepare pozole, tamales, pinole, and tortillas, could be at risk of contamination or substitution by GM crops. It wasn’t until 2013 that Mexico’s Supreme Court banned the planting of GM corn to protect the country’s biodiversity.

Mexicans have grown corn in milpa, the traditional polyculture of maize that includes other crops like squashes, tomatoes, beans, and more, as opposed to the monoculture that often takes place with GM crops. The 2013 decision halted GM corn permits like Monsanto’s applications to plant some 2.5 million hectares of GM corn, an area almost the size of Rwanda, according to Reuters. Transnational companies like Monsanto, Syngenta, PHI and Dow have appealed the decision since but to no avail.

The presidential decree is the latest in this decades-long battle to ban GM corn, but a full victory for the activists could still take some time. “Until we see the profound changes we can’t say how big of an achievement it is,” said Jönsson. “If it really goes to the root of it and challenges GMOs, then it’s a success.”

Jönsson, López, and Barros are all part of Sin Maíz No Hay País, a campaign that began in 2007 when over 300 organizations of farmers, Indigenous communities, consumers, and researchers came together in defense of Mexico’s food sovereignty. Sin Maíz No Hay País is hopeful that U.S. farmers and politicians will also see it as their own fight. “Mexico’s position is not to go against the imports of U.S. corn,” explained Barros, but rather substituting GM corn imports particularly. Back in October of last year, Deputy Agriculture Minister Víctor Suárez told Reuters, Mexico would seek deals with U.S. farmers to buy non-GM corn from them, a possibility Barros is on board with.

“There are corn producers in the U.S. who are willing to change their GM corn for non-GM corn and there are farmers already growing non-GM corn,” Barros added. “We are fighting the same fight.”