How scientists and regulators are fighting back against rampant honey fraud.

Vanilla. Olive oil. Truffles. The list of most counterfeited foods is a veritable who’s-who of culinary delights. On that point: Chefs, mead makers, and home cooks crave honey for its subtle flavor profiles and robust nutrients. But honey fraud can mean they pay top dollar for tony tupelo, but end up with wildflower — or worse, a honey that’s adulterated with cheap rice syrup.

In the past two decades, Americans have increased their per capita honey consumption from 1.2 pounds a year to nearly 2 pounds. Producers in the United States harvested 139 million pounds of honey in 2023 — that’s about 17 Olympic swimming pools or 4,000 concrete trucks worth. But even this heavy harvest isn’t enough to meet America’s demand. In 2022, the United States imported $745 million worth, and is the largest honey importer in the world.

The high demand and variable production of honey — like all farmers, bees can experience low-yield harvests — means that sneaky ways to fake, forge, and adulterate abound. Like adding water to a thick soup, honey supplies can be stretched by adding cheap plant-based syrups like corn or rice. In 2023, the European Commission found that nearly half of imported honey samples were adulterated.

Considering the breadth of the fraud, honey testing is one way to ensure a quality product makes it from hive to consumer. A number of testing solutions are in practice, but the financial costs and lingering turnaround time can deter many suppliers and packers from making the investment. But some scientists and honey aficionados are trying to create a database of honey “fingerprints” that can lead to a more accessible and cost-effective test framework. Their hope is to help tamp down on fraud while supporting suppliers and apiaries at the beginning of the supply chain.

The Circuitous Route From Hive To Table

Picturing honey may invoke images of identical gold liquid in bears with spout-caps lined up on store shelves, but honey has more than a one-note personality. Depending on the majority of flowers bees visit, honey takes on floral, acidic, medicinal, or earthy notes. Honey hues can range from pale, barely-there rays of morning sunlight to deep, molasses-like tones.

Honey varietals get their distinct color and flavor from the type of botanicals a bee visits. These are just a few of the samples being tested by Eastern Michigan University to map honey fingerprints.

·Credit: Sarah Derouin

While mead makers or chefs crave unique varietals for their concoctions, the general public usually prefers a more “classic” honey: sweet, golden, with few strong flavor notes. In part, this tried-and-true flavor arises from the way honey makes its way from apiaries to table.

Many honey brands at a grocery store typically originate from multiple beekeepers around the county and even globe. Honey makes its way into barrels and buckets where it’s then shipped to a central packing plant. There, honey from multiple floral sources gets combined in a giant vat to become a general “honey.”

“It’s sort of like mixing paint, trying to find a color that most people in the U.S. think is honey,” said Jeff Lee, a self-proclaimed “bee shepherd” and the owner/operator of Lee’s Bees in North Carolina. Lee takes his bees on the road, providing pollination services to farmers around the country. He explained that once individual honey harvests have been combined, it’s nearly impossible to trace where it originated from, or where any adulterated honey snuck in. And with so many intermediaries between beekeepers and packers, adulteration can easily sneak into supplies.

In the 1990s, a significant influx of cheap honey from China and Argentina was being imported to the U.S., depressing the worldwide price. By the early 2000s, the U.S. government imposed a large duty on honey imports from China and Argentina (184% and 37%, respectively).

“Companies were basically taking honey from China, they were shipping it to a third country or maybe just doctoring the shipping manifest.”

What happened next was unsurprising. “Companies were basically taking honey from China, they were shipping it to a third country or maybe just doctoring the shipping manifest … and thereby avoiding the duties,” said Eric Wenger, member of the board of directors member for True Source Honey. For instance, one year, 37 million pounds of honey came from Malaysia — but the American Honey Producers Association notes they only had the capacity to produce about 45,000 pounds of honey annually.

“The industry was in a very difficult position where this honey was flooding in,” said Wenger. In 2010, industry professionals came together and formed True Source, a non-profit organization that certifies and traces the source of honey.

Wegner explained that True Source has a certification process that focuses on conducting third-party audits in countries of origin to prove that these countries had legitimate beekeeping industries and that the honey shipped to the U.S. is legitimately from those countries. The honey is tested before and after shipping. “The entire purpose to say that if you said honey came from a particular country, you needed to go through the steps and provide the evidence to support that claim,” he said. While the process won’t help consumers buying generic honey in bears, branded honeys can contain True Source certification.

Originally, True Source used pollen testing methods to determine where a honey originated from. Microscopic pollen grains naturally make their way from bees into honey, leaving behind a biological map of their home, reflecting a geographic location. Now, Wenger noted they have moved on to more advanced technologies.

Honey Fingerprinting

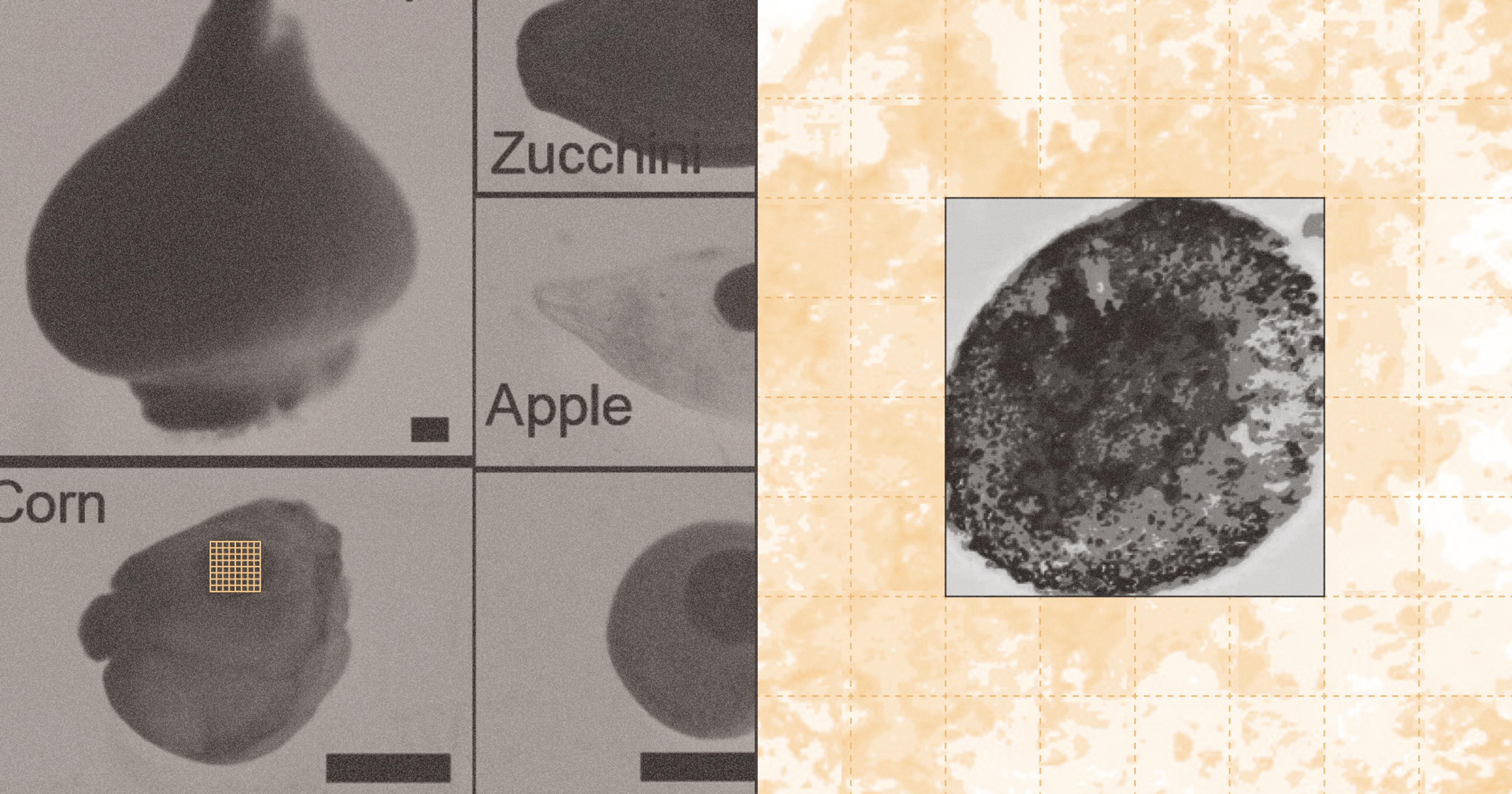

Honey testing can reveal the signature, or fingerprint, of that sample. Pollen mapping is one way to identify the provenance of a honey, but counting and identifying individual pollen grains can be time consuming. The method also doesn’t tell you if there are other sugars added to the honey.

Newer methods have emerged over the past couple decades focusing on the chemical signatures of honey, including NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy). NMR instruments work in a similar way as an MRI machine, but instead of mapping out the parts of a knee, NMR maps out the chemical molecules. The honey is slightly diluted with distilled water and run through a human-sized tubular machine. In the end, researchers get a printout of peaks and valleys that represent different compounds in the honey. While the NMR is expensive — instruments usually run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars — running the sample only relies on a simple prep with distilled water and a few minutes.

In the NMR readout, sugars create the giant spikes while the more subtle chemical signatures from harvested flowers show up as tiny speed bumps. And when it comes to identifying honey varietals, the devil is in the details. Cory Emal, chemistry and fermentation science professor at Eastern Michigan University, uses these small blips to fingerprint the signatures of different honeys.

Along with his team, Emal developed an algorithm that sorts the tiny NMP blips into categories. It’s an exercise in fine tuning. “We’re operating right on the edge of what we can detect,” Emal said. The algorithm must also be dialed in to pick up the nuances in the NMR results. “One of the problems with our technique is: What is a standard honey? There’s no standard orange blossom that everybody can point to and agree this is the platonic ideal of orange blossom honey.”

In the future, they hope to be able to run a honey sample and identify the varietals by the chemical signatures available to everyone. Ideally, the database would continue to grow with testing results being added by researchers and industry professionals. The more information, the better the database will be.

“One of the problems with our technique is: What is a standard honey? There’s no standard orange blossom that everybody can point to and agree this is the platonic ideal of orange blossom honey.”

Professional testing is one tried and true way of testing for fraudulent honey, but Wegner says to not waste your time with at-home testing. “The industry spends hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of dollars every year for very expensive, very sophisticated tests. And somebody’s like, ‘Oh, well, take it home and do the flame test, or the water test,’” Wegner said. “We just shake our heads, and it’s like, please don’t promote those tests, because if they worked, we would all do them because they’re very cheap.”

The next best way to ensure quality and origin is buy directly from local honey producers. “Where I take the bees, there are certain times of the year where there’s only one type of flower blooming. And it’s so dominant, the bees will only make that type of honey,” explained Lee. “I harvest it as soon as those flowers are done, and that’s how I personally control the quality.” When he moves his bees, he replaces the boxes of combs to collect a different varietal. The careful collection process allows him to confidently classify his sour wood honey from his water tupelo honey for consumers.

If you really want to support local bees and find a reliable product, Lee suggests getting to know your local beekeepers. “I just tell people, if you don’t buy it from me, just know who you’re buying it from.”