Select college cafeterias have long offered fresh local produce, some of it grown right on campus. But the newest farm-to-college programs offer students a crash course in every aspect of food production.

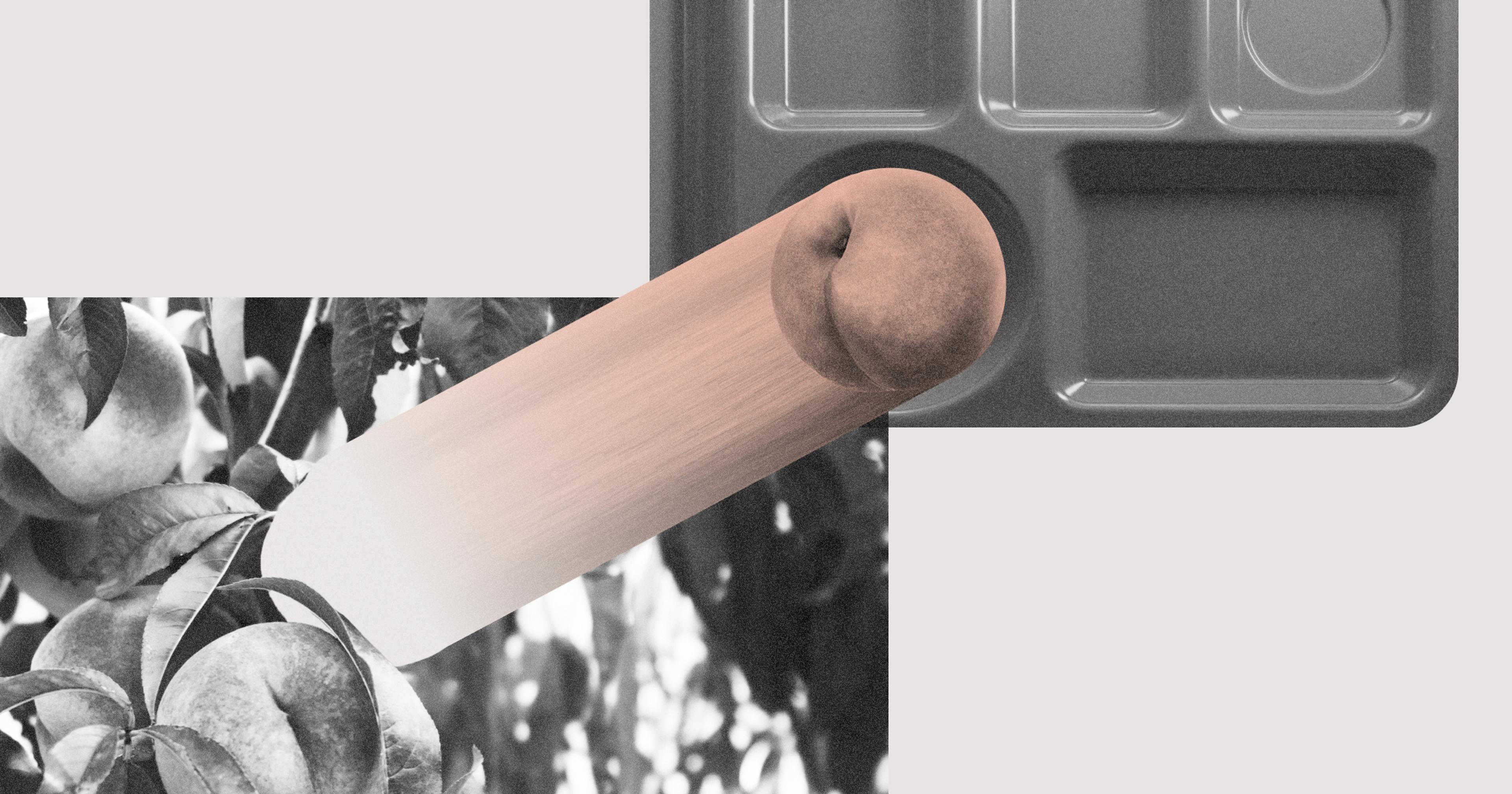

Avocado ice cream isn’t just a staple in the campus dining hall at Cal Poly Pomona (CPP) — it’s a collaborative work of art.

Start with the avocados: They came from an organic university farm where ag students learned in the “original classroom,” growing their own crops instead of learning about it in a book or video. Student teams were then involved in all stages from farm to spoon, from culinary development of the flavor profile, achieving the perfect green tint, designing and packaging cups and pints that illustrate the university’s origin story, marketing the product, and selling it at dining locations and the Cal Poly Pomona Farm Store.

Call it farm-to-college 2.0, a way for students not just to learn about the fundamentals of farming, but also to gain hands-on experience in every aspect of the supply chain. Our food systems are wonderfully complex; learning hands-on about growing, shipping, preparing, marketing, and selling gives college students a holistic, real-world experience. Programs like the one at CPP may well mark the future of ag education.

“Farm to school provides students with access to nutritious, high-quality, local food that supports learning,” said Jiyoon Chon, communications manager for the National Farm to School Network in New York. “It also presents opportunities for schools to procure in alignment with their values; for example, a school may source from a local BIPOC farmer for specific produce that’s culturally relevant for their student body,”

How the Ice Cream Gets Made

Every great collaboration has a point person. Jeremy Mora’s whole job is to act on behalf of both the CPP College of Agriculture and the CPP Foundation — a nonprofit that helps provide on-campus student jobs — to oversee agricultural operations and revenue-generating activities.

“This includes visiting ranches and animal units, as well as traveling to our external [commercial farming operations],” he said. Proceeds from all sales go toward student scholarships, on-campus student jobs, educational grants, and university projects like Cal Poly Pomona Farms Ice Cream. “My team and I manage the labs to ensure they are operational, sustainable, and reflect real-world conditions, creating an optimal learning environment for our students.”

While numerous schools have farm to university collaborations, none are quite as unique as their “salsa project,” he recalls, led by Gabriel Davidov-Pardo, professor of food science in the Huntley College of Agriculture. “This project involves creating a raw ingredient sourcing plan, understanding cost points, shrinkage, master packs, packing materials, and overall Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), making it a comprehensive learning experience that requires the collaboration of the entire team,” said Mora.

Carlo Arceo, assistant director at Cal Poly Pomona Enterprises, a nonprofit supporting the university through financial and facility resources, said they’ve developed an ordering process that supplies fresh ingredients so regularly, they often never make it into the fridge. “Every week I get an email about what’s available for that starting week. Sometimes they get the harvest that morning and we get it that same afternoon.”

CPP’s dining hall is no basic cafeteria as a result — week after week, it reflects seasonality and local harvests. “So currently, right now, like broccoli, cabbage, different types of cabbage, really different types of cauliflower. We have different colors — green, purple, white. We have Romanesco. Normally you only see that in fine dining restaurants,” Arceo said.

What Local Farms Gain

Aside from increased sales, farms have much to gain.

“For farmers, ranchers, fishers, and food processors, farm-to-school can serve as a significant financial opportunity by opening doors to an institutional market worth billions of dollars. Buying from local producers and processors creates new jobs and strengthens the local economy,” Chon said. He points to data including the USDA’s Farm to School Census, where 65.4% of school food authorities reported participating in farm-to-school activities (2018-2019), representing over 67,000 schools nationwide. This is a “significant growth” Chon said, since 2015, when just 42% of districts surveyed by USDA said they participated in farm-to-school activities.

Jill Burkhart, along with her husband Jeff, have owned a dairy farm in Dallas County, Iowa, for decades. Now called Picket Fence Creamery, they produce milk, ice cream, and cheese curds. Jill is an Iowa State University (ISU) alumni, where she now collaborates with her alma mater in what she calls a “win-win” situation.

“The challenges were few — it was just a matter of getting delivery and invoicing set up with the correct personnel. They did a great job helping us get on schedule with both. We have found the ISU staff to be extremely helpful and very nice,” she said. “We’ve had ISU students and staff visit our farm because they purchased our products on campus — it is great to talk to them and answer their questions. Also, we have regular ISU customers who stop by to pick up products to take home for semester breaks,” she said, adding that three local groceries also attract ISU customers for their products too. “This partnership is a great way to promote local, and keep dollars rotating in the local economy.”

Harvesting New Crops of Farmers and Food Workers

Where will the next generation of farmers, food producers, supply chain experts, and food industry marketing professionals come from? Collaborations like these, both colleges say.

“We probably employ more than 1000 students throughout the academic year. And then those students are provided with employment skills that are transferable onto the career that they want,” said Thomas Sekayan, chief operating officer at Cal Poly Pomona Enterprises. “We assign them strategically to certain job roles so they get paid and they learn, and it’s a fantastic resume builder, and they get that degree at the school.”

Iowa State’s original creamery and education program started over 150 years ago, just after the Civil War, thriving until 1969. Then, after a decades long hiatus, former director Stephanie Clark saw a “huge need” in 2009 for experienced students in the dairy industry, both on the farms and in food production industries. In 2020, after a 50-year hiatus, the ISU creamery was reestablished. Though ISU’s program isn’t old enough to have produced ready to work farmer graduates, that’s the primary reason ISU restarted the program.

“We didn’t have students graduating from ISU that had that hands-on experience,” said Sarah Canova, business manager of ISU’s creamery. Now, 20 undergraduates per semester work at the creamery, from formulation of ice cream and cheese, to making it, ordering, doing inventory, and through the retail store process. Another student is in charge of finance, and one manages social media — so it’s not just ag students. One student ended up working for beverage giant Califia Farms after learning about non-dairy product development, for example.

ISU sources cheese from the Burkhart farm, because they are “really flexible and willing to sell us approximately 70 gallons per month, and deliver it to our doorstep. It’s pasteurized, non-homogenized, and already packaged in gallons for us to pour into our cheese vats,” Canova said.

There is a lot of red tape at the university level to start a business like this, Canova cautions, so do your research if you want to start a similar collaboration. “Make sure you’re talking to all of your university partners to understand what you can and cannot do, and where you can and cannot sell,” she said. Most importantly keep the student experience front of mind, so the next generation is “fully integrated” into all aspects — for their own education, and for the future of food production.