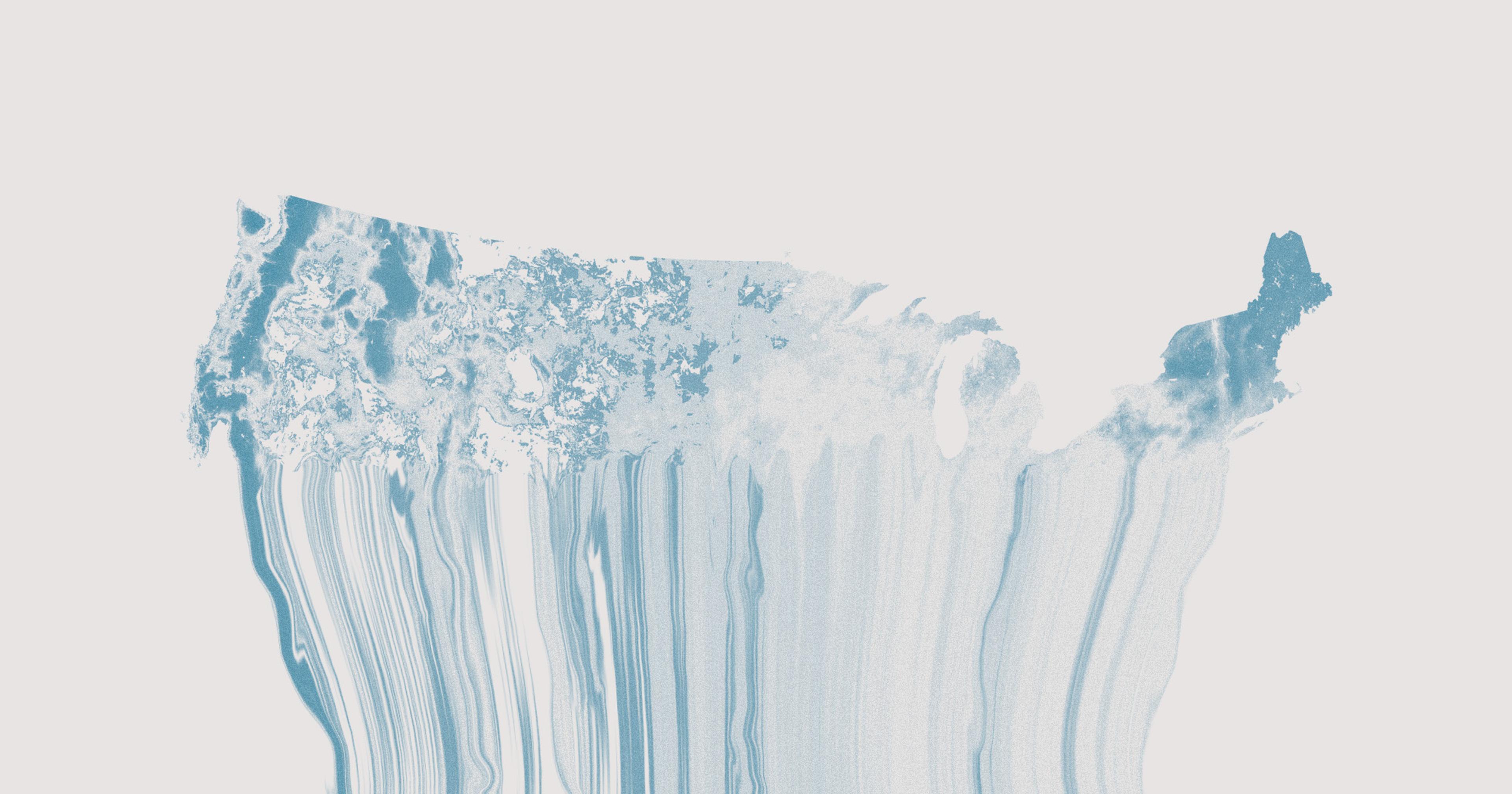

A new study measuring rare, cosmic atoms shows that soil erosion in the Midwest is orders of magnitude worse than we thought.

For Minnesota corn and soybean farmer Mike Seifert, erosion is obvious. On his family’s 100-acre farm south of the Twin Cities, there’s a marked difference between the pastureland and the cultivated areas. “If you stand at the fencerow, you’ll be two or three feet higher than the surface of the field next to it,” he said. “You can tell that at one point in history, that field was at the same height, and it’s not anymore.”

Fencelines like Seifert’s exist all over the Midwest — clear evidence to many that decades of intensive agricultural production have had a substantial impact on the region’s topsoil. But how do erosion rates from agriculture compare to the erosion that would have occurred naturally? A new study, published in the journal Geology in December, quantifies the difference between the two. The results are staggering: Erosion from agriculture, the researchers say, is taking place 10 to 100 times faster than natural processes, suggesting an urgent need for practices such as no-till farming and cover crops.

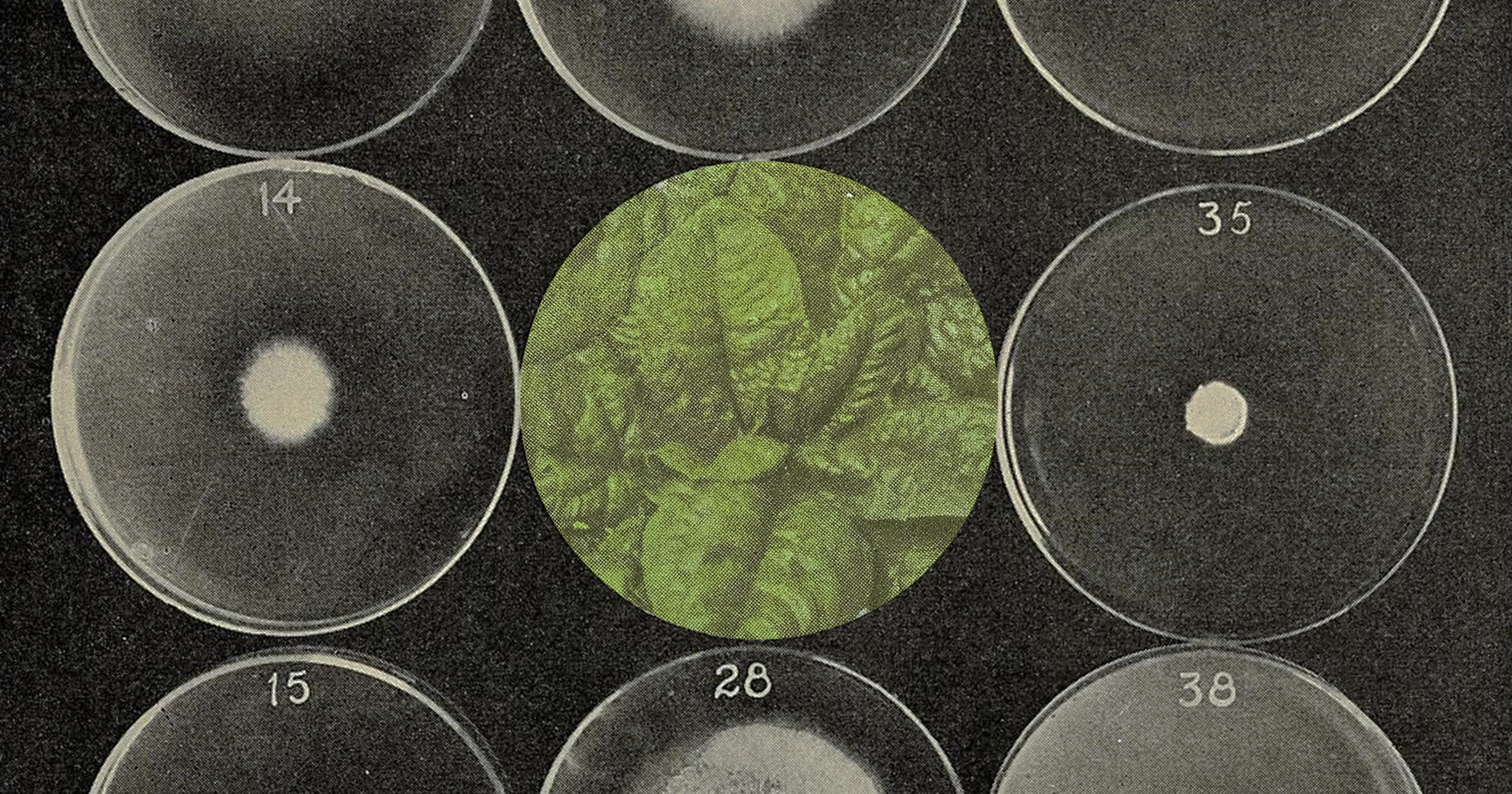

To get to that calculation, the researchers used a novel — and cosmic — method. First, the team collected soil samples from holes augered two to four meters deep in the ground at 14 native prairie sites around the region. Then, at the Purdue Rare Isotope Measurement Laboratory in Indiana and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, they processed portions of that soil to generate quartz. From that quartz, they could extract and measure Beryllium-10, a rare type of atom created when particles from space collide with earth’s atmosphere.

Isaac Larsen, the paper’s senior author, explained what space collisions have to do with soil erosion: “Stars exploding in the Milky Way produce high-energy particles that move through space and strike earth’s atmosphere. They smash into atoms and set off a chain reaction of things bouncing off of each other, and when they interact with oxygen and mineral atoms, they are so energetic that they smash them apart and produce Beryllium-10.”

Since there’s no other process on earth that creates Beryllium-10, researchers can use its quantities in soil to infer how rapidly or slowly a landscape is being eroded. In an area that’s being denuded fast, the minerals in the soil will have moved to the surface rapidly, and won’t have accrued much Beryllium-10, while slowly-eroding soils will accrue more of the element. By measuring the amount of Beryllium-10 in native prairie soils, the Geology paper provided an estimation of the Midwest’s natural erosion rate since the Ice Age: 0.04 millimeters per year.

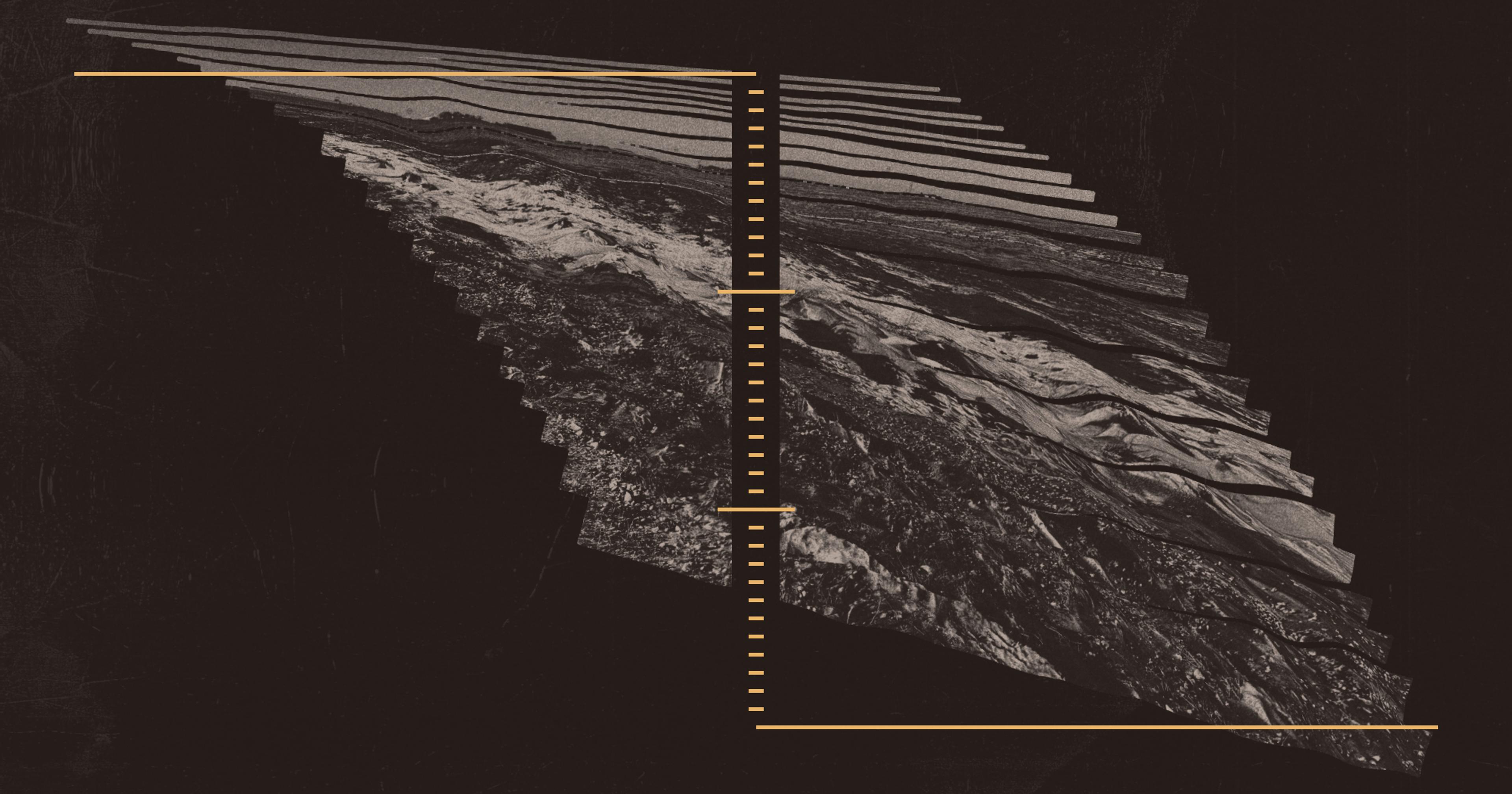

They compared this number to an agricultural erosion rate that they calculated in another paper published in February 2022, with a method similar to Seifert’s observations on his farm. Using high-resolution GPS devices, the researchers surveyed the drop-offs at 20 fencelines between native prairie and farm fields. They divided those heights by the amount of time since the land had transferred from the federal government to homesteaders, and found that agricultural erosion rates ranged from 0.2-4.3 millimeters per year — 10 to 100 times higher than the natural erosion rates measured using Beryllium-10.

Based on this comparison, the researchers argue that the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) soil loss tolerance standards, also known as “T” values, are too high in the Midwest — and that Beryllium-10 measurements should be used as the benchmark for new ones.

“If you sum up the effect of the erosion across the region, it results in several billion dollars of economic losses for farmers because of lower productivity,” said Larsen, adding that that figure doesn’t even include the cost of additional nitrogen fertilizer needed to offset the losses.

“If you sum up the effect of the erosion across the region, it results in several billion dollars in losses for farmers.”

Richard Cruse, director of the Iowa Water Center and a professor of agronomy at Iowa State University who has conducted research about soil erosion, agreed in an email that if the ultimate goal of the T-value is to have no soil deterioration, then the current tolerated soil loss “is much too high.” However, he added, the USDA also has to foster farmer engagement, and some worry that decreasing acceptable soil loss aggressively would discourage farmers from participating in conservation programs.

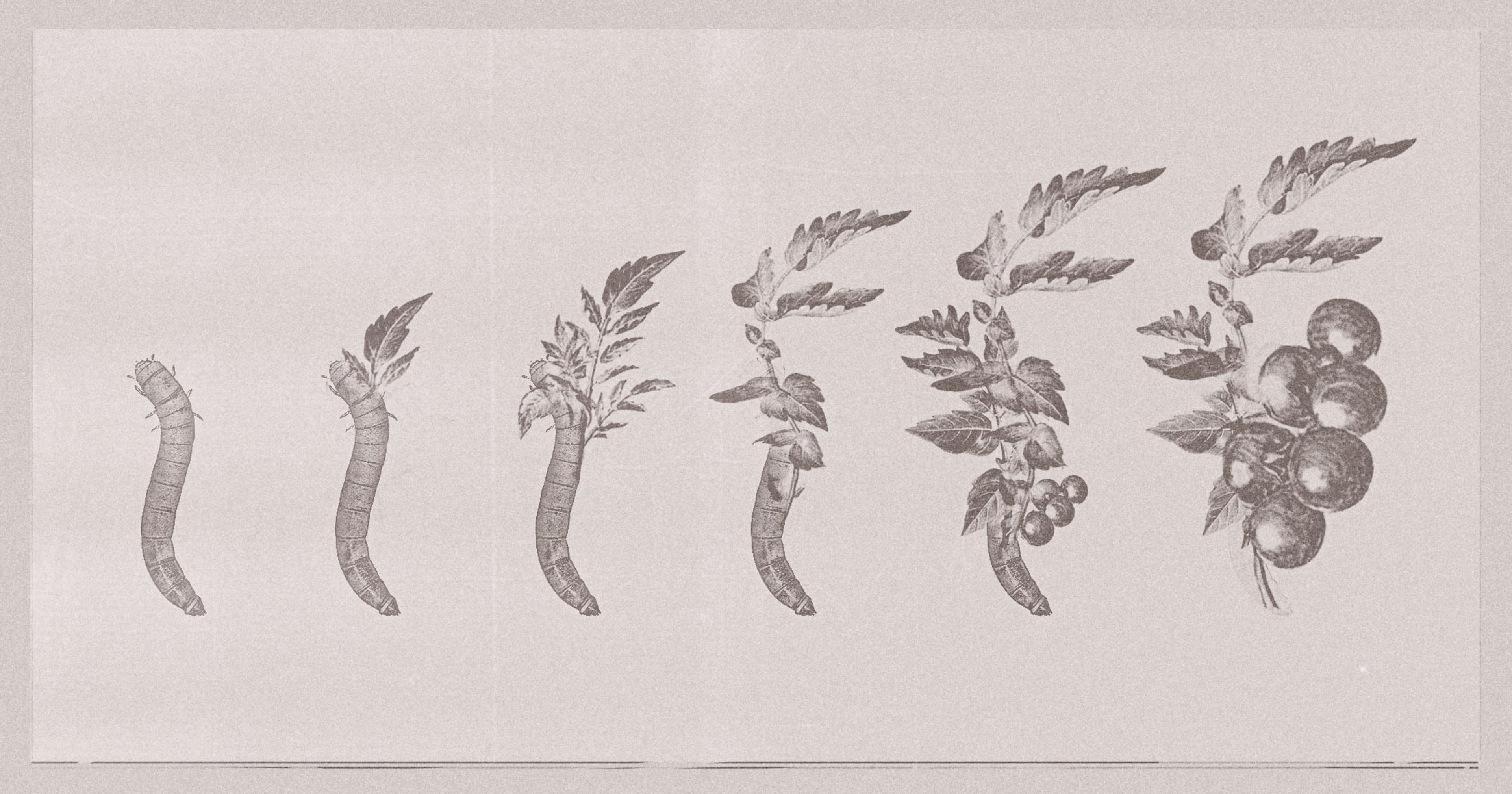

Both Larsen and Cruse agreed that soil conservation-minded farming practices play an important role in stemming the Midwest’s erosion problem. “No-till farming essentially will stop the erosion rates or reduce them to rates comparable to the [natural] rates,” said Larsen. “The next step is to get carbon back into the soil where it’s been lost. That’s another level and gets into soil-regenerative farming techniques that are not widespread at all.” This includes cover crops, crop rotation, and stopping the use of synthetic fertilizer.

Cruse seconded the need for cover crops. “Keep the soil surface covered at all times,” he wrote, “and armor [with grassed waterways] areas that are especially susceptible to water runoff in channels.”

Seifert, who is now in his fifth year using no-till farming practices, is the fourth generation of his family to farm the land. Of his farm’s 100 acres, 65 are cropland; the rest is a diverse mixture of wetland, pasture, and transition zones between them. There are also multiple different soil types. “There’s a lot going on in a small space,” he said.

For many years, the farm was diversified, with hogs, laying hens, and a large dairy herd. When his father took over, he got rid of the hogs and hens and focused on the dairy herd. “It was the ‘get big or get out’ era,” said Seifert. But after barely staying afloat during the 1980s credit crisis, his parents were ready to be done. They sold the herd and his dad went into construction, growing corn and soy on weekends and in his spare time.

“I wish I had started no-till 10 years ago, but I’m glad we’re five years in.”

“He was doing very conventional agriculture — chisel plowing the soybean residue and stubble, moldboard plowing the corn, spraying whenever it was advised, and doing lots of tillage passes in the spring,” said Seifert.

The land performed well for a series of years, until it didn’t. In particular, the topsoil was coming off of the hilltops and going into the lower areas, leaving them bald.

Seifert became interested in those types of practices through the teachings of North Dakota farmer Gabe Brown, who argues that farming in a more ecologically sound way leads to increased profitability. Seifert asked his dad whether he might be interested in trying something similar on their farm, and was surprised when he said yes. In 2018 and 2019, they transitioned the farm to no-till and cover crops — specifically winter rye — and started applying compost and compost extract to the soil, and diversifying their crops beyond corn and soy.

It was a particularly challenging year to transition to new practices, because 2019 was unusually wet. The Seiferts discovered another damaging effect of years of tillage: the tillage tools had compacted the soil into a hardpan about 8-10 inches below its surface. That meant that the rain couldn’t percolate into the soil, and it took a long time for the water to drain out of the muddy fields.

Seifert decided to trust that with time, the cover crop roots and the increased microbial activity in the soil would break the hardpan and improve the fields’ drainage. After all, he emphasized, extreme conditions like those are evidence of why farming practices focused on soil conservation are so necessary.

“Of the last four years, three have been extreme. I think this is what we can expect going forward — we’re not suddenly going to hit a string of typical years,” he said. “Weather events are getting more volatile. Our soil systems have to be more resilient. I wish I had started no-till 10 years ago, but I’m glad we’re five years in.”