Pollinator advocates are vocal about the urgent need to restore our native bee populations — just don’t make them honeybees.

When I told friends and family I was heading to Maine to study bees last summer, everyone assumed I meant honeybees. I think they were picturing me in a white protective suit, stylish metal smoker at the ready. Beekeeping is a popular back to the land hobby in both my rural hometown and New York City, where I now live. There are hives with informational signs in Bryant Park, two blocks from Grand Central Station, with a public bee-cam you can monitor from anywhere. Beehives have been offered as a luxury apartment building amenity; pollinator gardens are cultivated in every borough and all over the country. Through media reports and outreach efforts, many people have learned that bees are in trouble and they need our help.

That said, though keeping urban honeybees has been widely promoted as a conservation activity, I’d recently seen dissenting voices in the naturalist community. I was going to Maine to learn about wild bees instead.

“We’re saving the wrong bees,” instructor Nick Dorian said bluntly, calling honeybee hyping efforts “beewashing.” According to Dorian, one hive of honeybees can consume the nectar and pollen that could feed 100,000 wild bees. Supplementing diverse wild bees with the unhealthy, voracious honeybees in a recreational hive can seriously impair a biodiverse ecosystem.

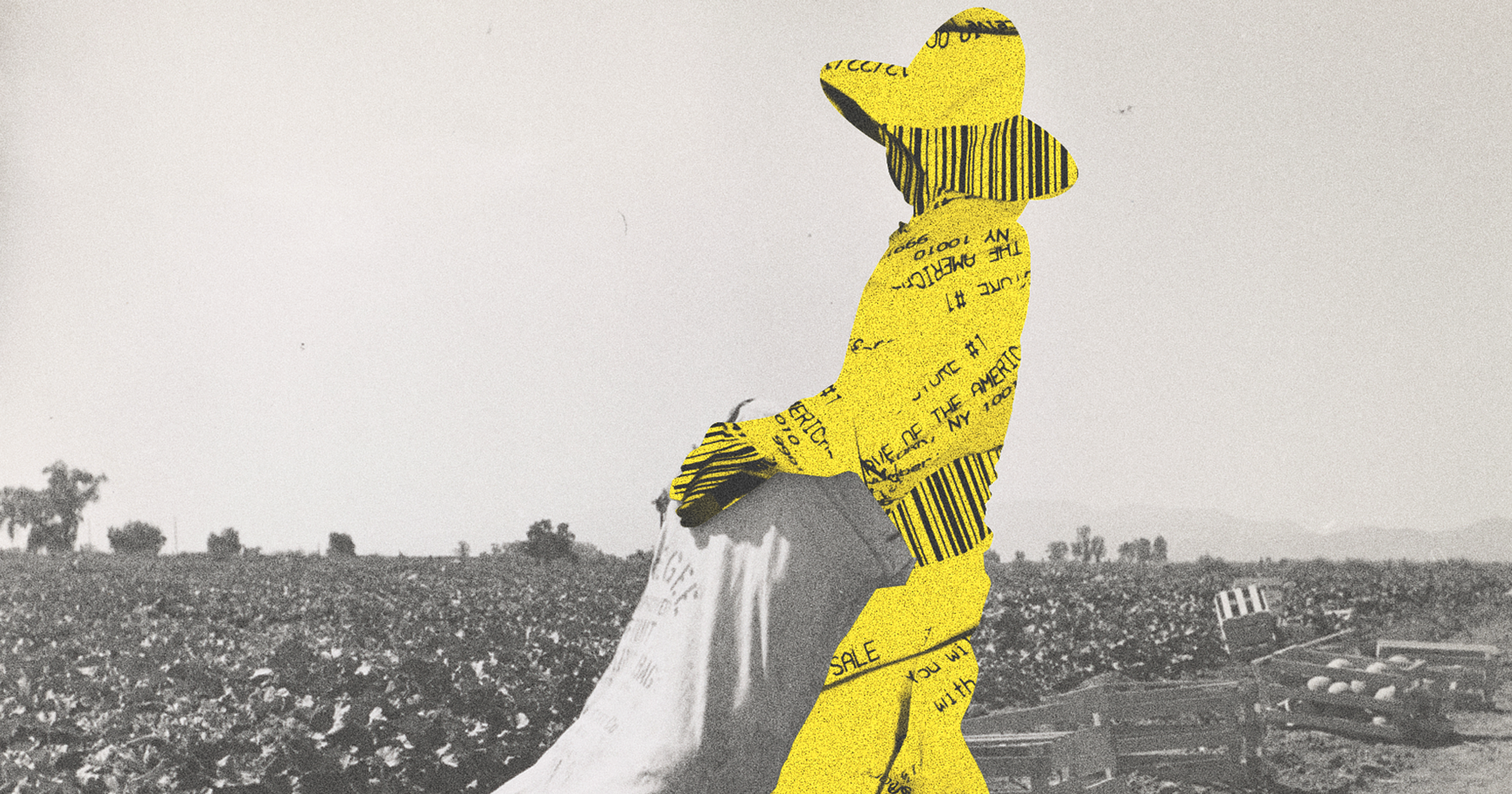

Native bee species do have special skills as native plant pollinators, but putting a dollar sign on those skills may be counterproductive. The intrinsic value of a given bee’s existence and the unplumbed interdependencies between co-evolved plant, fungi, and animal species cannot be priced. When illnesses are introduced or species endangered, we stand to lose much more than the cost of a pint of blueberries. Such is the toll of cultivated hives.

My bee school was offered at the Eagle Hill Institute in Steuben, Maine, a few towns north of Bar Harbor. Led by PhD students Dorian and Max McCarthy, The Natural History of Native Bees: Biology, Ecology, Identification and Conservation promised an education in everything bee-related — as long as it wasn’t a farmed bee.

Although I’m an experienced birdwatcher, before signing up for this class I’d never really thought about varieties of bees. I knew there were honeybees, the species I would soon learn as Apis mellifera, and some yellow fuzzy bumblebees who seemed angry most of the time. Turns out there are 4000 different North American bee species!

“We’re saving the wrong bees,” Dorian said bluntly.

They come in gorgeous blues, greens, and reds as well as good old yellow and black. Most native bee species are solitary and nest in single cells dug in the ground or plant stems, not communal hives. Unlike honeybees, these species don’t have queens or drones. A third of bee species specialize in eating pollen, not gathering nectar. Fifteen percent are “cuckoo” bees who don’t make their own nests at all, instead sneakily laying their eggs into another species‘ nest. They range widely in size and preferences for food, nesting habitat, and temperatures, and they are only active and likely to be seen at particular months or weeks of the year. As in birdwatching, these differences help watchers identify bee species.

The course was Sunday to Saturday; from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. we’d move from lecture to microscopy, to field work, back to lecture, then finish with evening discussions and movie viewing. Everyone at Eagle Hill shares a passion for natural history so at each meal I learned about my classmates’ gardens, research projects, and studies.

Dorian and McCarthy took inspiration from ornithologists in writing a new online field guide, Field Guide to Wild Bees, and in designing the class. Birdwatching is no longer a private list jotted down in the back of a book; more and more birders contribute to the international research database behind the EBird and Merlin apps. Bird lovers have been using increasingly powerful citizen science tools to document their research-grade field observations.

The interest in urban beekeeping and pollinator gardening show how much people already love bees and want to help. But my instructors insist that to save wild bees, you shouldn’t start a rooftop apiary or buy a butterfly bush. Instead, watch carefully and use the INaturalist app to document and identify. Once you see what bees are around, you can help them stay healthy and raise their families.

Whenever I hear the buzz of a bumblebee I consider how I used to be afraid the bees were angry at me.

“No one who has seen a bee nesting in a stem will want to cut that down. Once they see it, they’ll guard it with their life,” Dorian explained, miming an older gardener he had worked with, looking stern while covering the stem with a tomato cage.

The first morning of class I learned about the bumblebee’s buzz. They are sonicating — vibrating their wings as they fly. When they land on plants, their vibration is just the right frequency to release pollen from crops like tomatoes, chilis, and peppers. Without the buzz, there would be no blueberries.

In the afternoon there was a break in the rain and the bumblebees, lovers of sun, came out. For the first time, when I heard their buzz I knew they weren’t warning me off like a rattlesnake; they were doing their incidental job of pollinating while feeding themselves and their families. I recorded my first two field identifications of bee species, the two-spotted bumblebee (Bombus bimaculatus) and half-black bumblebee (Bombus vagans), and I felt my experience of being outside shift and deepen.

How to Help

Our wild bees are being threatened by widespread habitat destruction and hit hard by climate change. Their life cycles are highly dependent on temperature and the timing of emergence from hibernation, when their food and nesting conditions are ideal. The ubiquitous use of pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides can imperil all of this — and put our food supply at risk.

“If it kills a mosquito, it kills a bee,” said Dorian. “Wild bees are critical for production of crops like blueberries, pumpkins, and apples, and loss of wild bees from farms means that farmers face greater risk of not having enough pollination services.”

Once I learned about the pressures on our wild bees, I understood that local rooftop honey was not going to be the solution. Happily, city dwellers like me can help support the wild bee diversity around us while enjoying our time outside.

If you garden at all, even just in a flower pot on a stoop, you can keep the needs of pollinators in mind. Provide food in the form of native species that flower at different times of year. Make mini nesting habitats by leaving leaves and stems over the winter. Refrain from using pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides, even the organic ones.

But can you help bees by hanging out in urban parks, or simply taking a summer walk? Yes! When I got back to New York City after bee school, I noticed wild bees foraging in scruffy street side weeds and in cultivated flower beds. Yet for most bees scientists lack basic natural history data, i.e. where bees are, when they are active, and what they are doing throughout their life cycles. Through INaturalist, citizen scientists like me (and you?) can make meaningful contributions by recording in detail what we see, a valuable contribution to both scientific research and pollinator advocacy.

Now whenever I hear the buzz of a bumblebee I consider how I used to be afraid the bees were angry at me. I think of the blueberries, pumpkins, and peppers that exist because of this special vibration. I consider the tiny baby bee larvae, fed by pollen. And how every part and behavior of each wild bee species evolved over millions of years to work in competition or cooperation with the other living and nonliving parts of their ecosystem. The bees would be right to be angry, because our human actions are destroying this system. It is time to listen to what the bees are actually telling us — and to take action.