In American agriculture, a few companies call the shots. Austin Frerick’s first book shows that we may know even less about them than we realize.

Rob Larew, president of the National Farmers Union (NFU), contends that farmer stress is on the rise. “That stress is very tied to the financial pressures that farmers feel today,” he said. “As the amount we receive for the goods that we are selling continues to go down, while the inputs that we are having to buy go up, that is a stress, right?”

Larew has a view into the system that few others do: NFU membership totals almost 200,000 American family farmers, ranchers, and rural residents. He notes that the psychological pressures farmers face have their provenance in the financial constrictions that shape their daily lives. Regardless of what they produce or where they live, many farmers are encountering diminished choice as a result of agricultural monopolies. Fewer, and bigger, actors set the terms at essentially every level of the food system, leaving many farmers without much say in their own realities.

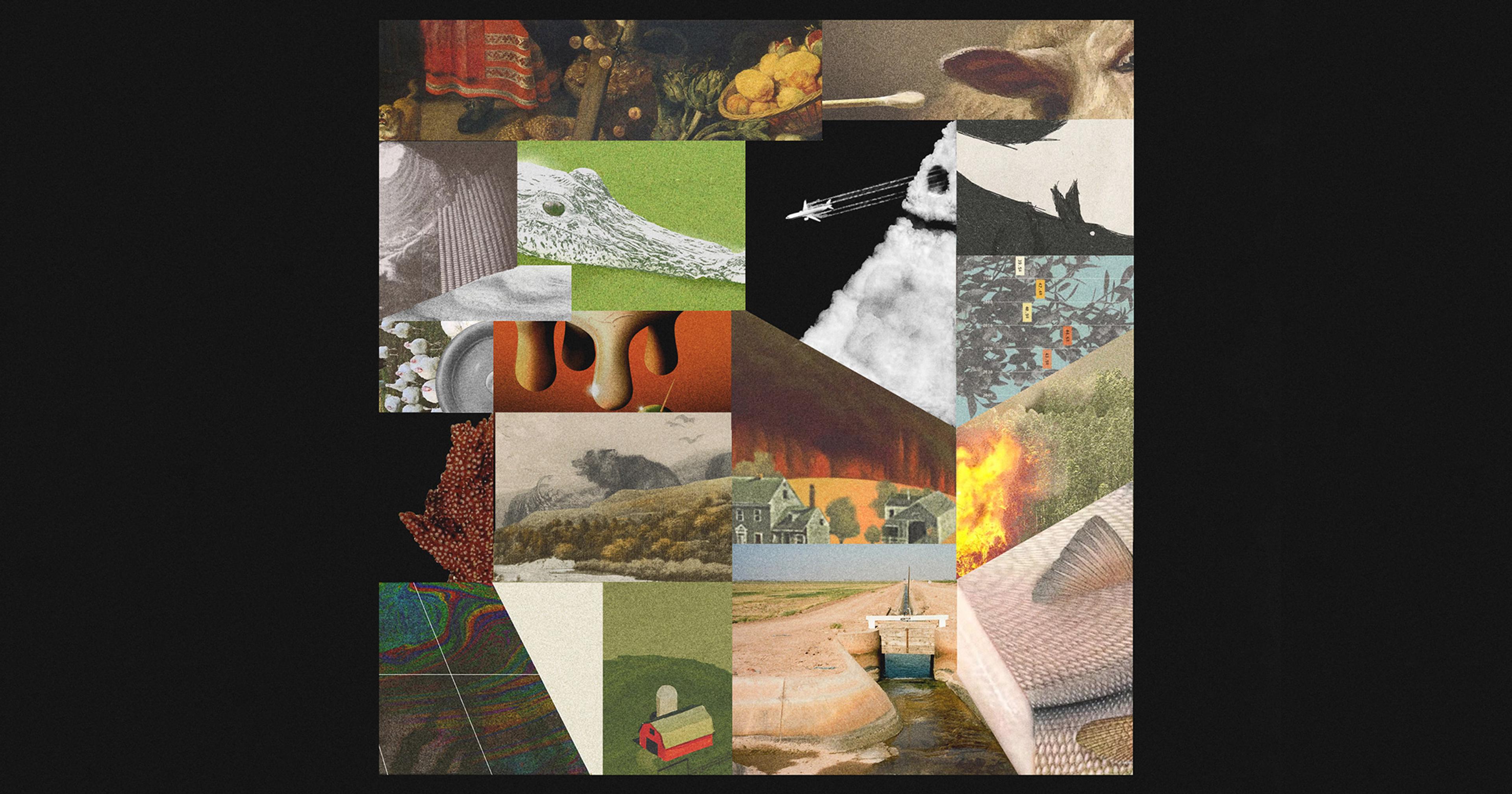

In his first book, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, Austin Frerick picks up this thread. He writes, “The American food supply chain — everything from seeds to baby formula — has fallen under the control of a narrow group of individuals, leaving family farmers and local businesses fighting an uphill battle just to stay in business.” Frerick is an expert in agriculture and antitrust policy whose family has lived in Iowa for seven generations. His book unpacks the playbooks of seven monopolies whose owners — modern-day “barons” — have near-complete control over their areas of the U.S. agricultural system.

Frerick takes apart their strategies patiently and methodically, almost as though he is turning an engine upside down to figure out its workings. As Larew points out, farmers in most states, with the exception of Colorado, do not even have permission to fix their own machines due to manufacturing monopolies. Developing and sharing a clear understanding of agricultural consolidation is a way Frerick hopes to draw agency back to farmers.

Among the book’s seven monopolies, some, like Walmart or Driscoll’s, are instantly recognizable to a general audience. Others, like Iowa Select or Reimann’s, may be less so. Frerick examines how the shift towards corporate consolidation coincided with deregulation and the decline of antitrust enforcement. The companies‘ owners moved from being garden-variety capitalists to industrial tycoons not only through individual enterprise, but because they could. Each company only gained power in the last 40 years, taking advantage of new loopholes in the system.

“A lot of stories either focus on the person or on the structure. I wanted to understand — how does someone like this emerge, and what does it mean from a societal standpoint?” Frerick said on a call. “I didn’t just want to be like, ‘Let’s gawk at rich people.’” The barons are windows into the structures that stand behind them. They anchor larger discussions about check-off reform, illogical corn and soy subsidies in the “Wall Street Farm Bill,” and Walmart’s monopoly over SNAP dollars, just to name a few.

Despite the policy focus, this book reports from the trenches of the food industry: fields, hog confinements, slaughterhouses, fluorescent-lit grocery aisles. Frerick addresses how Big Ag intersects with concrete issues of labor, immigration, the environment, food scarcity, and more. One of his most shattering revelations is the death of an immigrant farmworker from Honduras at Indiana’s Fair Oaks Farms in January 2021. During a 12-hour shift, the 47-year-old father of three got pulled into manure equipment and died from asphyxiation.

“A lot of stories either focus on the person or on the structure. I wanted to understand — how does someone like this emerge, and what does it mean from a societal standpoint?”

Worker safety in the dairy industry can be dire: ProPublica recently conducted a year-long investigation into immigrant farmworker conditions after an 8-year-old child died at a Wisconsin farm. Frerick was the first to report on the death of the farmworker at Fair Oaks, however, which is both a behemoth dairy operation and a dairy-themed amusement park. “The person died in the area where they take you through on the tour, and I was there afterwards. It’s a tourist attraction,” he said.

Layers of corporate abuse also make it harder for immigrant farmworkers to speak up. Larew said, “Much of that labor is not self-reporting for fears of retaliation. That is detrimental to the entire food system starting at the farms.”

Frerick noted media complicity in the barons‘ ascent. With their vast coffers of money, companies are free to invest in shaping narratives as they like. Frerick said, “The current state of media means that these barons can create their own realities.” In February, for instance, New York Attorney General Letitia James brought a case against meatpacking giant JBS for greenwashing. JBS had taken out a full-page advertisement in The New York Times claiming that it would reach Net Zero by 2040, without any plan to actually get there. In another instance, Cargill, the world’s largest private company, supported research concluding that organic food was not more nutritious than non-organic food. Frerick devotes chapters to both companies in his book.

“One of my bragging points to this book is that I have nearly a thousand citations,” he joked. Though his writing style is restrained, it simmers with damning facts and figures. Take, for example, his chapter on the Iowa hog industry. Frerick’s family worked in Iowa’s food system, and when he was young, “the landscape was alive.” Now, the same fields have given way to corn and soy monocropping and large-scale hog production — Iowa Select is the worst offender. Using census data, Frerick calculated that 26,000 Iowa farms have stopped raising pigs since Iowa Select launched in 1992.

“Austin’s book is refreshing in how he weaves it by telling these family stories, in how in these examples the industry has become so consolidated,” Larew said. Christopher Leonard, author of The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business, added, “There’s this cluster of people who talk about agribusiness [living] on the coasts, like in D.C. or San Francisco or whatever, and not enough of them on the ground here in the Midwest where the business is rooted.”

“There’s this cluster of people who talk about agribusiness [living] on the coasts, and not enough of them on the ground here in the Midwest where the business is rooted.”

Interestingly, 20th-century deregulation was a bipartisan affair. “Rather than working to limit concentrated power, politicians in both parties have either helped entrench powerful interests or attempted to conduct policy in a manner that is agnostic to power,” Frerick writes. Similarly, he said companies like Iowa Select have avoided accountability by fostering “close relationships with state politicians on both sides of the aisle to roll back regulations.”

This deregulation undid Roosevelt-era antitrust policy under the New Deal, which benefited families like his own. Frerick suggests a return to rigorous antitrust policing of the type Roosevelt would be proud of. After all, his barons are incarnations of the very Gilded Age robber barons that antitrust policy managed to curb. Though we might feel unmoored in the face of consolidated power, Frerick argues that we actually have a template for the fight.

The idea of being in a new Gilded Age is not specific to this book. In the 2023 book Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America, federal prosecutor Brendan Ballou writes about “a twining of big business and big government that finds profits by creating and exploiting legal gaps and obscure government programs.” And Jesse Eisinger, author of The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute Executives, said that the Gilded Age is a “useful comparison to think about where we are today compared to the 18th and 19th centuries for a variety of reasons. We had a period then of rapid economic growth and vast and increasing wealth inequality, and concentrated industries and ownership of those industries, which gave the wealthy disproportionate power in the country.” He went on, “It’s a model for understanding where we are today.”

Across party lines, there is dislike for big business, and momentum for change seems to be building. A January survey by the Pew Center found that Americans agree large corporations have a negative impact on the U.S, with a wholly bipartisan 68% of respondents saying so. Meanwhile, 88% of Democrats and 87% of Republicans believe that small businesses have a positive impact on the country. Monopolies have not fared well in the court of public opinion.

Federal Trade Commission Chairperson Lina Khan, who Frerick cites as a mentor, has taken on large corporations during her tenure and written about how they keep farmers‘ costs high. Larew said that the current government has “given voice to that challenge” to a greater extent than previous ones. In his newsletter, Matt Stoller, author of Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly and Democracy, writes, “We’ve re-injected the anti-monopoly philosophy into America, and there’s no going back.”

“For a lot of family farmers, it’s not just [about] my farm and my crop this year, but am I going to be able to keep the farm next year.“

As always, the way forward is not going to be easy. In his conclusion, Frerick outlines what could happen if we take action as well as if we continue on our present path. The contrast between change and yet more consolidation, environmental damage, and hollowed-out communities is sobering. Despite that backdrop, Frerick recognizes that the New Deal was not a panacea. White farmers benefited from the deal at the direct expense of Black farmers, driving many off the land. Without reducing policy’s potential for impact, a tension remains at the heart of the book’s framing: the way the period of progressive reform is held up as an example, and the sense that it never actually worked at all.

Perhaps this is inevitable when working with such a fraught national history. But it is important to acknowledge that policy has its limitations — indeed, creating lasting change to the U.S. food system might require a fundamental shift to the political system as we know it. Rather than falling back on the example of the New Deal, we need to fully reimagine the future. “The lands we inhabit — with fractured histories and debts owed — tell stories about ‘pasts’ we do not want to repeat,” Ashanté Reese, author of Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C., wrote recently in MOLD magazine.

“Where some see inevitability, the rest of us see possibility,” Reese continued. There are histories, presents, and futures of resistance, revolt, and reimagination at the grassroots. The future is uncertain.

“For a lot of family farmers, it’s not just [about] my farm and my crop this year, but am I going to be able to keep the farm next year, and keep that hopefully generational support for the farm?” Larew said. As the barons demonstrate, power is difficult to give up. But it doesn’t stick around forever.