Xylazine, one of the most common sedatives in large-animal veterinary care, is increasingly being mixed with fentanyl for human use. The results are disastrous.

Are you familiar with xylazine, recently declared an “emerging threat” by the White House? On the street, often mixed with fentanyl, it’s known as tranq dope, sleep cut, or zombie heroin. Besides significant overdose risks, it has the potential to cause festering open wounds, necrosis — sometimes described as “rotting skin” — and eventual amputations. It’s turning up in 50-90% of street drug samples in many parts of the country, including Pennsylvania and Western Massachusetts.

It’s also one of the most commonly used sedatives for large-animal veterinarians in the country.

“We want horses to have calm experiences with veterinary procedures,” said Sally DeNotta, an equine veterinarian at the University of Florida. “There isn’t really any reason in modern day veterinary medicine to be performing procedures on animals that are scared or physically restrained. It’s really not humane. So we use xylazine for both the benefit of the animal and the safety of the people [in the room].”

Yet on the streets, the drug is a clear danger to humans: On April 12, the Biden Administration declared fentanyl mixed with xylazine as an “emerging threat to the United States.” The report cites a recent spike in overdoses — a 1,127% increase in the south, 750% in the west, more than 500% in the Midwest — as the motive behind the declaration, which will lead to an interagency working group and an eventual “national response plan.”

Xylazine is also the target of newly proposed, bipartisan legislation introduced by Senators Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), and Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) Among other things, the Combating Illicit Xylazine Act would classify the drug as a Schedule III controlled substance, and enable the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to “to track its manufacturing to ensure it is not diverted to the illicit market.”

In veterinary medicine, xylazine was first introduced in the 1960s as a sedative during veterinary procedures. It fell out of favor as a treatment for smaller animals some years back, and is primarily used now with horses and cattle, according to Bernd Driessen, professor of anesthesiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. “Xylazine is a very valuable sedative, and centrally acting muscle relaxant,” Driessen said. Though there are a couple of alternative sedatives for horses — detomidine and romifidine — there’s nothing comparable for cattle.

The drug’s emergence as a fentanyl companion has been rapid and relatively recent — DeNotta said she’d never even heard of the possibility for human use prior to a few months ago. “My understanding for most of my veterinary career was that the alpha two agonist sedatives were very dangerous for humans,” she said. The conception is affirmed by Driessen, who says humans are about 10 to 20 times more sensitive to xlyazine than animals.

DEA stats reveal that In 2021, xlyazine was connected with at least 1,281 overdose deaths in the Northeast and 1,423 in the South. Because the animal tranquilizer is not an opioid, an overdose can’t be reversed by naloxone, also known as Narcan. Atipamezole, which can reverse the sedative’s effects, is used in veterinary medicine, but has not been approved for human use by the FDA.

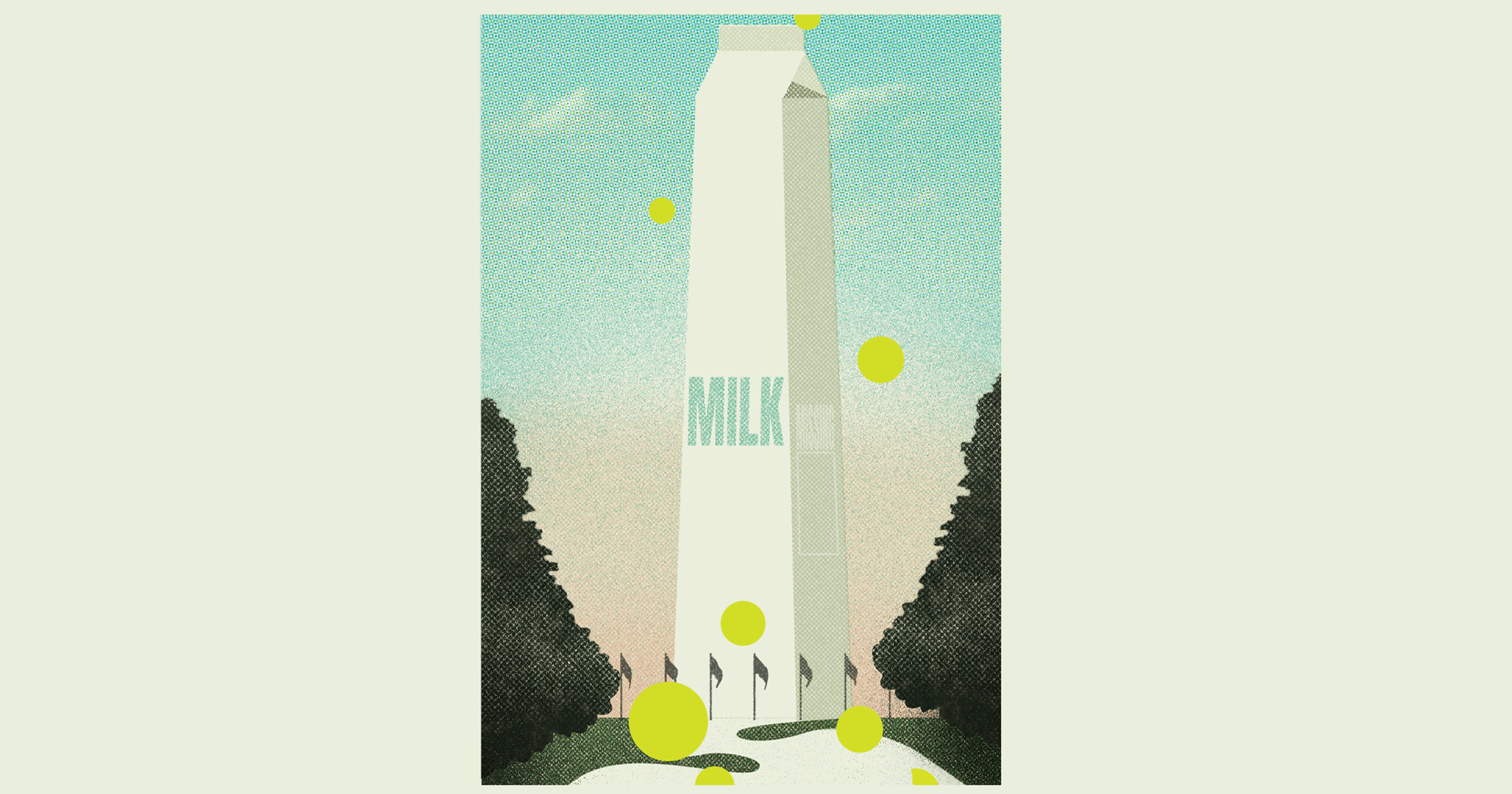

Given the clear danger to people, it may not be surprising that the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) has endorsed the federal legislation that would reclassify xylazine as a controlled substance, a designation that would add significant layers of security to its veterinary procurement and usage. Before signing off, however, the organization engaged in efforts to ensure veterinarians would still have access to the drug, and that it wouldn’t be “scheduled federally at a higher level than necessary.” (Schedule III would classify xylazine at the same level as ketamine and anabolic steroids, one level below fentanyl, opium, and methamphetamines.)

This bill “ensures that folks like veterinarians, ranchers, and cattlemen can continue to access these drugs for bona fide animal treatment,” said Sen. Grassley in a statement, a sentiment echoed in quotes provided by Cortez Masto and Senator James Risch (R-Idaho), another bill cosponsor.

A significant open question is whether the xylazine on the streets was diverted from the veterinary supply chain, or manufactured specifically for human consumption. The AVMA claims it “does not believe there is substantial diversion of xylazine from veterinary channels,” while an epidemiological study in Philadelphia theorized that people started obtaining it during the pandemic using online veterinary prescriptions and other supply chain diversions. Driessen said his understanding is that the xylazine is being produced from labs in Asia and Eastern Europe, not “being provided/sold by vets criminals or stolen from trucks of LA vets.”

“Vets have to keep track of how they use the drugs they order and if they were to sell xylazine to illegal entities, it would be quickly noted that their order amount is rising,” he said. “That alerts folks quickly.”

“I would predict that many vets stop using it because the bookkeeping is too complicated for them and also difficult to handle in a field practice situation.”

Whether or not the xylazine problem is stemming from our current veterinary supply, there is no question that scheduling it as a controlled substance would add non-trivial burdens to the veterinarians who rely on it. A quick scan of the comments on AVMA’s announcement reveals sentiments like “We don’t need another controlled drug!” and “Veterinarians shouldn’t be saddled with more paperwork that does nothing to stop drug abuse and will only make it harder and more expensive to use xylazine.”

DeNotta, who works out of a hospital, said she could adapt to new regulations, just as she has with veterinary drugs like ketamine that were labeled controlled substances due to human abuse. Her sympathies lie with “ambulatory veterinarians,” who would need to implement significant security procedures when traveling with xylazine to treat cattle in the field, for example. Driessen thinks that might be enough to put mobile vets off using it at all.

“I would predict that many vets stop using it because the bookkeeping is too complicated for them and also difficult to handle in a field practice situation,” he said.

Whether or not the Senate bill ultimately passes, the current White House and DEA focus on xylazine means that we’re likely to hear about more enforcement efforts in the months ahead. There are also new efforts to reduce xylazine overdoses, like a project out of Brandeis University that is cataloging the drug’s prevalence on the street and conducting research on how to mitigate its harms. (There are currently no approved reversal options such as naloxone.)

For her part, DeNotta is saddened by the whole situation. “I think that the illicit drug problem in this country is disheartening,” she said. “And it’s unfortunate that it changes the medications that we use much to the benefit of our profession and our patients. It’s unfortunate when they become more difficult to use or even acquire because people are using them for unsafe, unlawful reasons.”