The proposed pipeline would enable ethanol plants to sequester carbon dioxide out of state. It is profoundly unpopular.

In December 2014, an agent from the pipeline construction company Energy Transfer Partners came to Steve Hickenbottom’s farm outside of Fairfield, Iowa, and asked him to sign over an easement that would allow them to construct part of the Dakota Access Pipeline through 170 acres of his land. That conversation “started out nice,” he recalls now, but at the end the agent gave him two options: “Sign this over voluntarily, or we’ll take it via eminent domain.”

Hickenbottom didn’t sign, and true to its word, the company filed a condemnation enforcing eminent domain. Over four days in the summer of 2016, he watched a cohort of bulldozers, welding trucks, and excavators dig a 30 foot-by-30 foot trench, bury a pipeline in it, and cover it back up with soil. Hickenbottom grows soy, oats, and hay for cattle on about 1,000 acres that have been in his family for nearly five generations. He estimates damage to his land from those four days at about $200,000, and that doesn’t account for loss of productivity.

“When you give them eminent domain, or rather when they take it from you, you lose control of the land,” he said. “It’s just like legal thievery, I don’t know how else to explain it.”

When a similar agent from a company called Navigator CO₂ Ventures appeared at Hickenbottom’s door last summer, he knew it was time to fight back — he and his fellow farmers would have to get organized. “They bulldozed their way through the first time, and we didn’t know anything about it,” he said. “But now we’re way better off this time as far as getting things filed and talking to representatives and senators.”

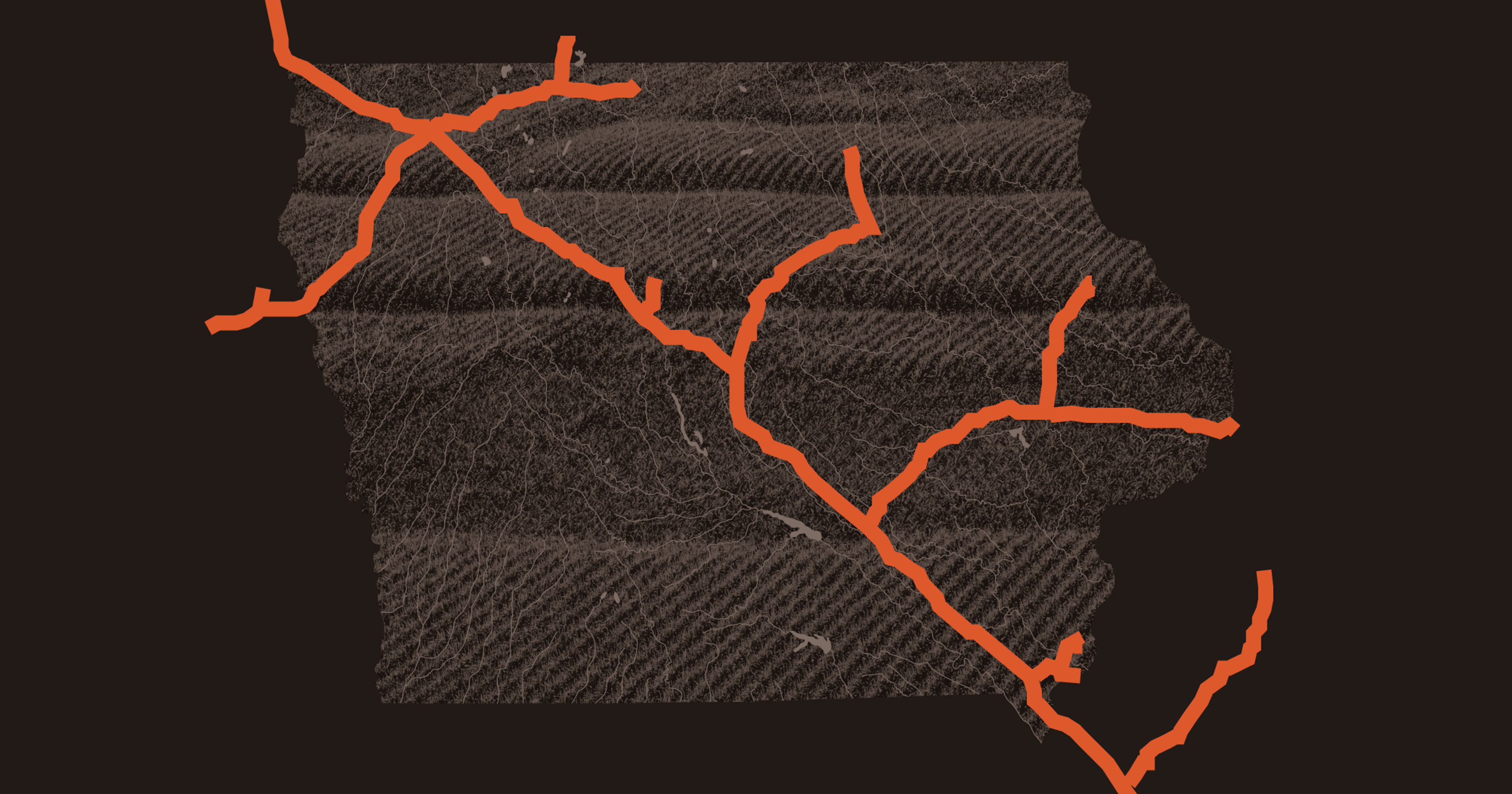

The Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden Administration’s historic suite of climate legislation, included new and lucrative tax credits to limit the greenhouse gas emissions for fuels, and with those incentives came new business opportunities. Navigator is one of three companies, along with ADM-Wolf Carbon Solutions and Summit Carbon Solutions, that are seeking to construct a network of pipelines across the state of Iowa.

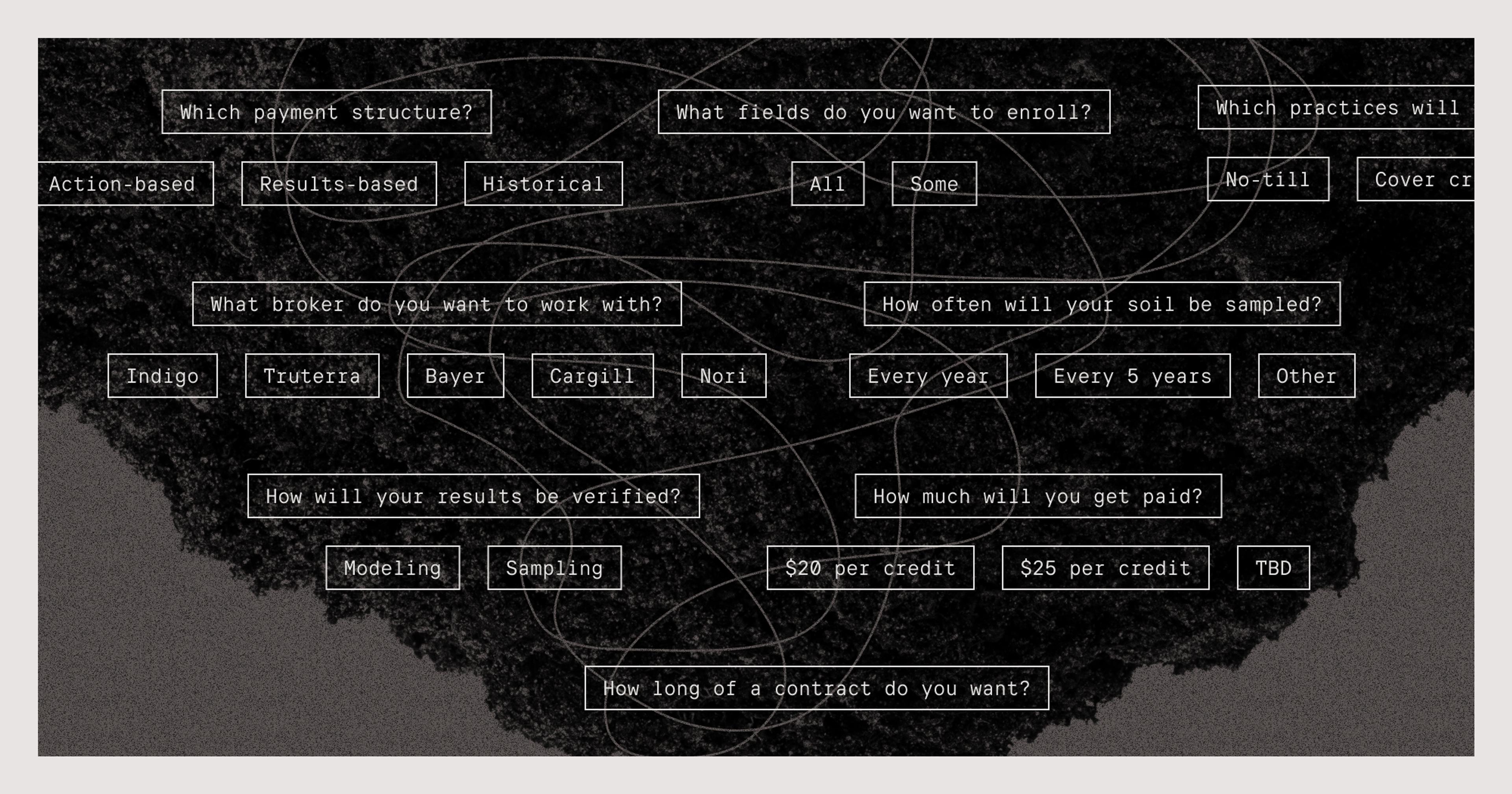

These pipes would transport carbon dioxide (CO₂) captured at industrial facilities that produce the climate-warming gas — primarily ethanol plants — and deliver it to North Dakota or Illinois for sequestration. Taking advantage of the new tax credits by building a proposed network of pipelines could deliver $2.16 billion to the Iowa ethanol industry, according to an estimate commissioned by the industry group Iowa Renewable Fuels Association.

To the casual observer, these pipelines represent a kind of multilayered boon: stimulate American industry, support farmers who grow corn for ethanol, and reduce carbon emissions. But the true climate benefits of such a pipeline are very much up for debate, and farmers whose land has not yet recovered from construction easements for the Dakota Access Pipeline are skeptical of letting a new company come in and tear up their fields for profit. This proposed carbon dioxide pipeline, which has been touted as both a climate solution and a path for Iowa corn to remain valuable, has forged a rather unlikely alliance between environmental activists and a sizable contingent of Midwestern farmers who have organized to block it.

“It’s not like this coalition hasn’t happened before, but the thing that’s really unique about this is we’ve got even more diverse characters involved: QAnon and far-right Trump characters, mainstream Republican fiscal conservative folks, urban liberals, a lot of Democrats, Independents, a lot of environmentalists,” said Mahmud Fitil, land defense director with the Indigenous activist group Great Plains Action Society, describing the movement opposing the pipelines. “And so far in Iowa it’s taken shape as focusing at least legally on the vein of private property rights, which is the hallmark of conservative values in the Republican party.”

Issues With Ethanol

The climate-saving potential of ethanol has long been the subject of substantial debate. In 2005, the Bush Administration passed the Renewable Fuel Standard to incentivize the domestic production of ethanol and other biofuels as a supplement to gasoline. This legislation was framed as a helping hand to farmers that would create a more valuable destination for corn harvests, and also as a way to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Ethanol is far from an emissions-free fuel; both its production and combustion emit carbon dioxide. Ethanol advocates argue that this is offset by the CO₂ that gets sequestered in the soil in the process of planting and growing corn. But the effectiveness of that sequestration varies wildly according to factors like farming methods and land use, which results in a wide range of appraisals of the fuel’s sustainability.

The U.S. Department of Energy, for example, cites 40% carbon savings from using ethanol in lieu of gasoline; whereas one study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment estimated that the carbon footprint of ethanol is actually 24% greater than that of conventional gasoline, due to the losses of carbon-sequestering forest or grassland that have been converted to grow corn.

Just as the climate benefits of biofuels are disputed, so too are those of the methods of carbon storage and usage incentivized by the Inflation Reduction Act. The geologic burial method, in which liquid carbon dioxide is injected deep into the earth, presents some risk of earthquakes or leakage of CO₂ back into the atmosphere. More controversially, the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits can apply to the practice of using carbon dioxide to more efficiently flush oil from wells, which has obvious negative implications for the climate. Many climate advocates point to carbon capture and storage as a practice that enables polluting sources of energy.

“They shouldn’t need any reason beyond: ‘This is my land and I don’t want the pipeline going through it.’”

To that end, the Sierra Club’s position is that investment in carbon capture and storage to support the continued or increased production of ethanol is a “false climate solution.” Furthermore, they argue that the proposed carbon dioxide pipeline poses a threat to the rural communities it runs through. It’s a relatively new innovation in hazardous material transport, with 5,000 miles of carbon dioxide pipeline currently operational in the United States. The “hazardous” designation is due to the risk of highly pressurized liquefied CO₂ exploding out of a leak in a pipeline, where it can displace oxygen and potentially suffocate bystanders. In 2020, a carbon dioxide pipeline explosion in Satartia, Mississippi, hospitalized 45 people.

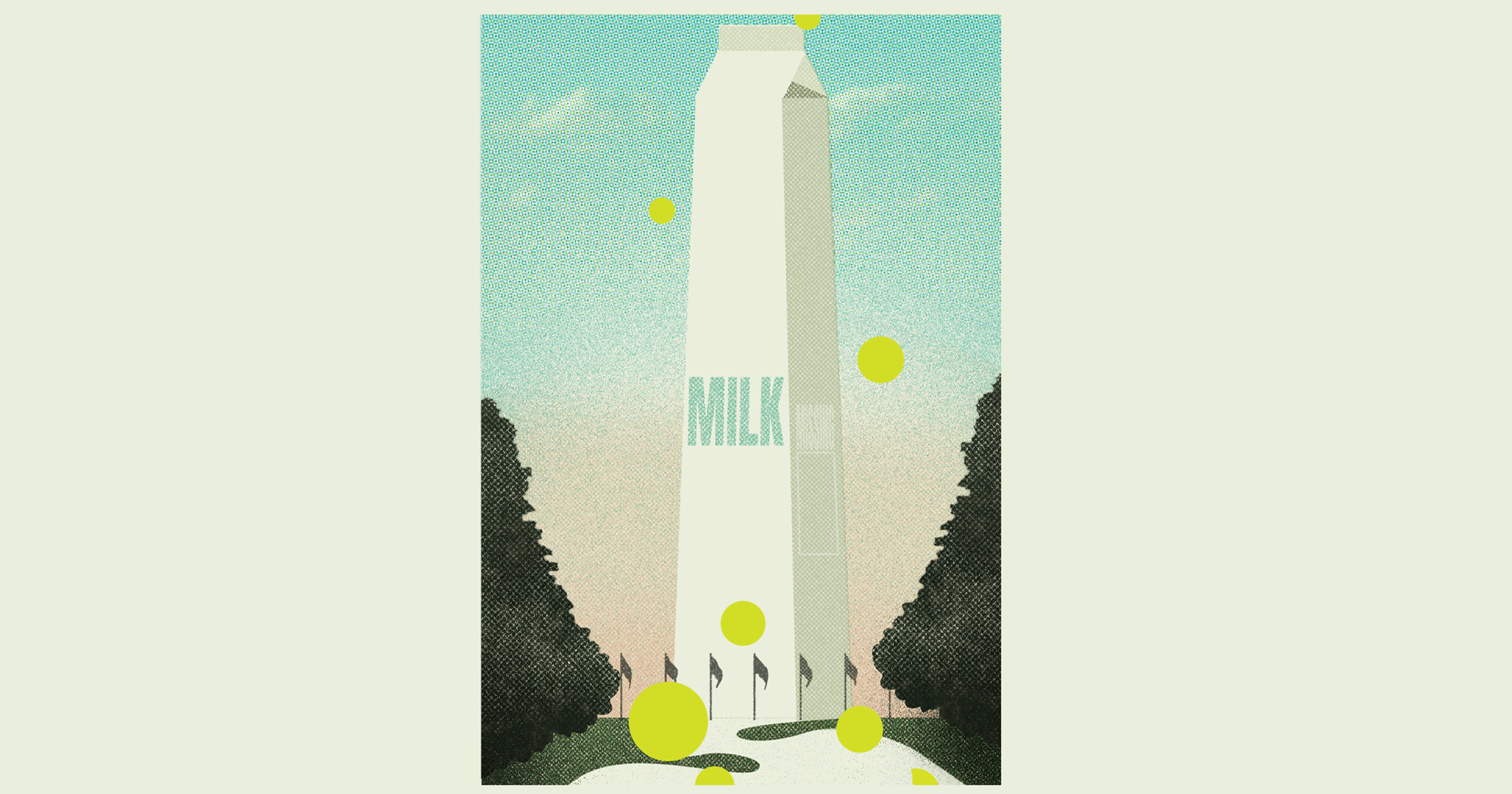

Meanwhile, ethanol industry groups and their supporters argue that one pressing reason to construct these pipelines is that businesses in other states are already utilizing the Inflation Reduction Act’s new tax credits, leaving Iowa ethanol plants at a competitive disadvantage. Furthermore, a growing list of states that includes California and Oregon have legislated a low-carbon fuel standard to go into effect within the coming decade, which would exclude ethanol plants that do not use carbon capture and storage technology from those markets. There’s also growing demand for low-carbon ethanol in the development of “sustainable aviation fuel.”

Pipeline proponents say that if Iowa ethanol plants begin to get shut out of the national market, corn farmers in the state will lose a lucrative destination for their crops. (Roughly half of Iowa corn goes to ethanol production.) In March, the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association commissioned another study that estimated that profit losses to Iowa corn farmers without the opportunities afforded by the proposed pipeline would average 85% by 2030.

“If the loss in competitiveness was so large that grain ethanol plants started closing, that would have a tremendously negative impact on this part of the country — there’s no doubt of it,” said Robert Brown, professor of agricultural engineering at Iowa State University, adding that he wasn’t sure whether low-emissions fuel standards will actually lead to plant closures.

Pipeline Popularity

In an era in which farmers face both increasingly slim profit margins and erratic growing conditions, one can imagine that anything that would stave off an alleged threat to farm income would be incredibly popular in a state like Iowa. And yet, the carbon dioxide pipeline is exactly the opposite: A poll in March showed that 78% of Iowans oppose the use of eminent domain to build it.

“It should be a bedrock conservative principle that you don’t take people’s use of their land away from them,” said Donald Ray, a retired teacher and small-scale farmer who raises sheep and cattle in Ringgold County. “And the Republicans should be very against that, only using it as a last resort.”

State Senator Jeff Taylor, a Republican who represents a deep-red district in Iowa’s northwest corner, has sponsored a number of as-yet-unsuccessful bills in the state senate that would either block or provide significant hurdles to the use of eminent domain in the construction of this pipeline. He sees the use of eminent domain to enable the construction of a pipeline that yields no public benefit or service to Iowans in violation of the fundamental Republican value of “respect for the Constitution and property rights.”

“These are private projects for private gain and they have no business qualifying for eminent domain,” he said. “Ultimately my argument is that no matter if the concerns of the landowner are justified or not, or whether you or I think they’re good, they shouldn’t need any reason beyond: ‘This is my land and I don’t want the pipeline going through it.’”

Jessica Mazour, conservation coordinator for the Iowa Chapter of the Sierra Club, further attributes opposition to the pipeline to an increased wariness of corporations’ desire to profit at the cost of community safety. That’s a recurring theme in the letters of opposition that 23 Iowa municipalities have sent to the Iowa Utilities Board urging it not to approve the use of eminent domain for construction. They cite the pipeline’s proximity to schools and homes, and the lack of emergency services to deal with the potential fallout of a leak like the one that happened in Satartia. Norfolk Southern’s unpopular response to the disastrous train derailment it caused in East Palestine, Ohio, in February has only augmented these concerns.

“There’s all this concern that Norfolk Southern isn’t being honest about what’s in the air, is the water safe,” said Mazour. “And that’s what’s gonna happen here? We’re gonna have to trust these private companies to say, ‘You’re fine?’ There are a lot of similarities, bringing hazardous chemicals to people’s communities where we don’t have adequate safety regulations.”

Fighting Back

On March 22, Steve Hickenbottom drove from his farm to the Iowa House of Representatives in Des Moines to join about 100 other protesters who wanted to have their voices heard as the House debated a new bill related to pipeline construction. It would require the companies constructing the carbon dioxide pipeline to obtain voluntary easements from 90% of property owners before being able to enact eminent domain. The protest was organized by the Sierra Club, but he estimates about three-quarters of the attendees were farmers and landowners.

The bill passed the House with a 73-20 vote, and will now proceed to the Iowa State Senate, where Sen. Taylor predicts it will have an “uphill battle,” due to some legislators’ allegiance to ethanol interests.

This is a rather remarkable state of affairs that demonstrates the continued political influence of the ethanol industry, given that the Iowa state legislature is Republican-controlled and the issue of using eminent domain to construct pipelines is evidently unpopular among Republican constituents. Former Iowa Governor Terry Branstad is now a major spokesperson for one of the pipeline companies. Branstad also nominated two of the three members of the Iowa Utilities Board, which has the power to implement eminent domain to construct pipelines.

But energy around the opposition campaign remains strong. Mazour said that the key difference between the Sierra Club’s campaign against the Dakota Access Pipeline and its efforts against these proposed carbon dioxide pipelines have to do with the organization of landowners. With Dakota Access, individual farmers were seeking individual legal representation and there wasn’t much of a cohesive effort among concerned parties. For this case, the Sierra Club has helped hundreds of farmers across Iowa gather together under representation by the law firm Domina Law Group, based in Omaha, Nebraska, which used a similar group lawsuit model to fight the Keystone XL pipeline.

“I guess what really sparked people’s interest in fighting back this time was just: We don’t want this to happen again, we’ve seen what happens,” said Mazour.

“The Dakota Access Pipeline really left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth — for the Indigenous nations for sure, and the white landowners as well. They came in and ran roughshod over everybody,” said Mahmud Fitil. “And now there’s this large groundswell of grassroots organizing even among conservatives, which you don’t normally see.”

As for Hickenbottom, I asked if this fight to protect his family’s land was an emotional issue for him. He responded: “Well, that might be one of the greatest understatements of the year so far.”