In Virginia, a non-profit is preparing to welcome Black farmers on farmland donated by a white couple as a form of land reparations.

When Natasha Crawford grows her mustard greens, garlic, and squash in a quarter-acre plot 23 miles south of Richmond, Virginia, she’s taking part in something bigger than her own hobby farming.

A restaurant health inspector by day, Crawford signed an in-kind lease of the acreage on the Petersburg Oasis Community Farm as part of a more expansive vision for Black farmers in the state: This site acts as an incubation program organized by the Central Virginia Agrarian Commons (CVAC), a non-profit seeking to bolster the area’s food systems by turning land over to Black farmers. Farmers can lease a plot of land here, as Crawford did with her Healing Hope Urban Gardens.

“It’s really hard for small, independent Black farmers to try to do things on their own, and try to purchase land and not really have the support that I feel that you would need,” said Crawford.

The CVAC launched in 2022 after white Amelia County residents Callie and Dan Walker donated an 80-acre portion of their farmland as a form of reparations. The Walkers, who stopped farming on that acreage once it was donated, realized the land housed a plantation on it until the 1960s, when Callie’s father bought the property and tore down the house.

The Walkers signed a deed of gift drafted by Agrarian Trust, an Oregon-based national land trust working to advocate for collective land ownership and stewardship through multiracial coalitions. The deed permitted the CVAC to take complete ownership of the land, which doesn’t yet have any Black farmers toiling the soil.

Crawford works on the Petersburg plot while the Amelia County property has yet to invite farmers onto its land. In a way, the Petersburg site acts as a training ground for farmers who have their sights set on a bigger plot at Amelia.

First, the CVAC has to build a retreat-slash-bed-and-breakfast building that will together house around 16 farmers, in order to “allow for folks to have a place to say and to also have an educational opportunity and learn how to farm,” said Duron Chavis, a founding board member of CVAC based in Richmond.

Each farmer can receive a lease for the land based on their needs, Chavis added, noting that CVAC is seeking to acquire more land to “replicate the model … and to ensure farmers can farm without going into debts.

Each farmer will receive a lease for the land based on their farm enterprise needs, Chavis said. “Our goal is to connect urban and rural agricultural enterprises that have been created by BIPOC community members to facilitate long-term alternatives to land access.”

“I’ve seen how we have limited access to capital to purchase land, so it made a lot of sense to try to figure out how we lock that in so that we can establish that long-term land tenure.”

The property will eventually become a multi-functional space where Black farmers can live, work, and grow their agricultural enterprises without debt. But farmers will need to pay for their own business expenses, Chavis clarified.

“While we received the land we did not receive any funding or anticipate any funding to invest in the farmer business or to subsidize their farming endeavors,” he said.

Construction is expected to be completed by early 2026.

Chavis views the Petersburg farm as a starting point for BIPOC farmers who may be interested in low-cost or in-kind leases that will soon be available at the Amelia County acreage. As an example, Crawford doesn’t pay for her lease but instead will soon help the CVAC by managing a greenhouse that’s under construction.

This is an opportunity that Chavis said is vital for marginalized farmers in Virginia, if not the entire country. “As someone who has spent years farming in urban environments, I’ve seen how we have limited access to capital to purchase land, so it made a lot of sense to try to figure out how we lock that in so that we can establish that long-term land tenure,” he explained.

The CVAC is part of a growing movement of young Black Americans advancing the idea of reclaiming land that has been lost or stolen. Of all private U.S. agricultural land, white Americans account for 96 percent ownership, according to the USDA. At the peak of Black land ownership in 1910, Black farmers owned 14 percent of the country’s farmland, a notable accomplishment less than five decades after slavery was outlawed.

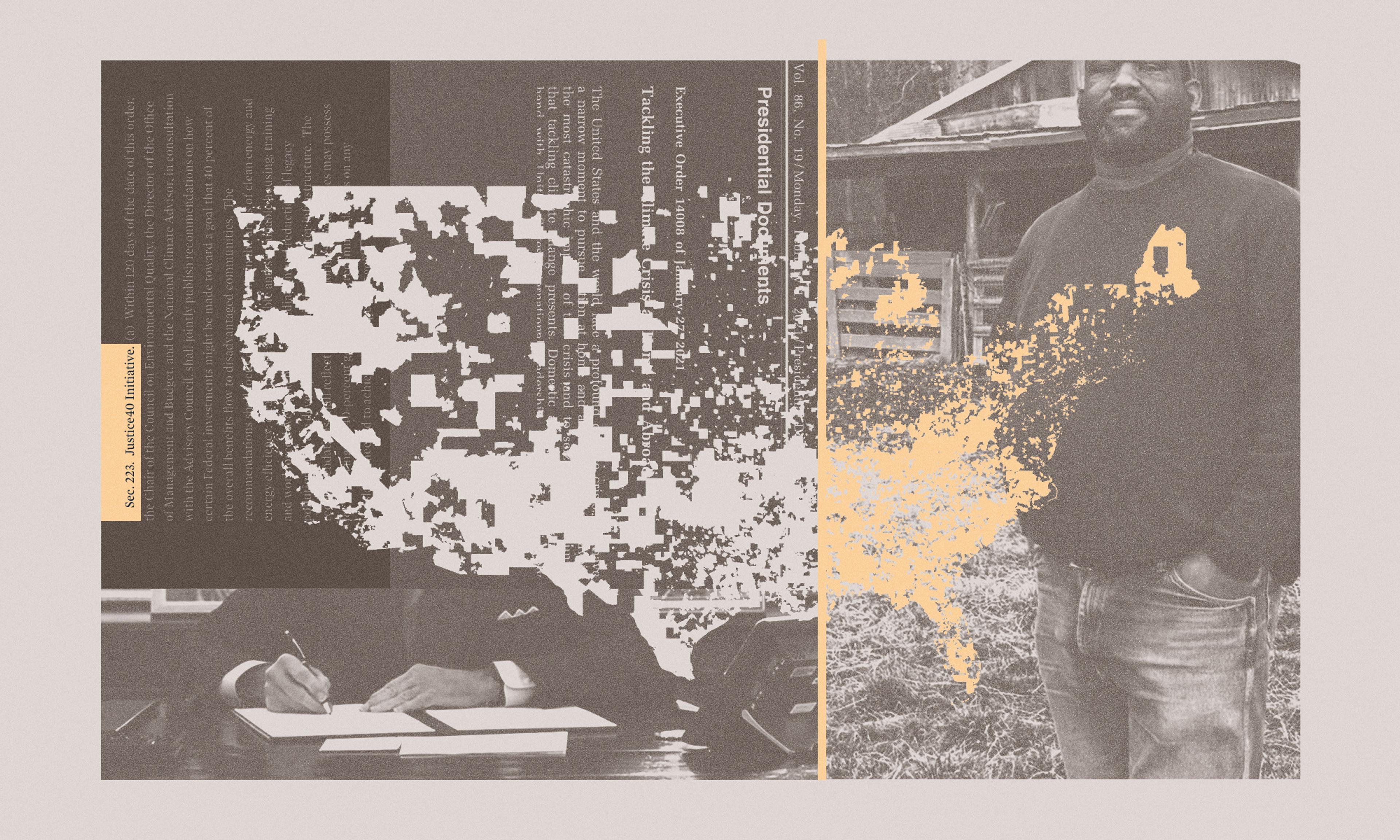

In a statement published by the American Farmland Trust, the organization outlines how Black, Indigenous, and farmers of color have been “subject to discriminatory federal, state, and local policies and practices, from being denied land ownership in the early 19th and 20th centuries, to receiving fewer government loans compared to their white counterparts.”

Healing Hope Urban Gardens

Today, Black farmers can still encounter troubling reminders of a violent past. “When we approached the county to rezone the land to make it more amenable for us to build housing, members of the community in Amelia County were very racist towards this project,” Chavis recalled. “They expressed things like how they didn’t want to have strangers living in proximity because they like to walk around their neighborhood. That type of dog whistling around Black farmers coming onto this land to farm was an example of the type of hostility that exists in rural communities.”

What the CVAC has accomplished should act as a blueprint for other states, said Kenya Crumel, director of the Black Land and Power sector at the National Black Food and Justice Alliance. “Many other marginalized groups in this country have received some form of reparations, but we’re the sole group that is told ‘Move on, sorry, you don’t get any reparations.’”

That’s not entirely accurate. In August 2024, the Biden administration announced it would begin distributing millions of dollars in relief checks to farmers who have experienced discrimination in farm loan programs. More than 43,000 individuals will receive payments ranging from $10,000 to $500,000. Also, more than 20,000 farmers and ranchers who were unable to secure loans due to discrimination will receive between $3,500 and $6,000.

Tyrone Cherry, a Black farmer who runs the youth farm component of Petersburg Oasis, appreciates the immense potential for what CVAC is aiming to do. “I’ve seen how farmers teach others about equipment to use, the skills they can apply to their crops, and it’s that intergenerational learning that is helping engage young farmers here,” he said.

He said young farmers gain valuable experience learning not just the hands-in-the-soil approach to farming but also the business side of it. “Because we bring our fruits and vegetables to farmers markets, we’re teaching them about the connection between food and community,” Cherry said.

Crawford points out how the CVAC projects can have a ripple effect that go beyond influencing the trajectory of Black farming opportunities. “It’s not just going to benefit Black and brown communities,” she said. “At no point has any farmer ever said they’re only going to their veggies for underrepresented groups. They’re going to grow them for whoever wants them.“