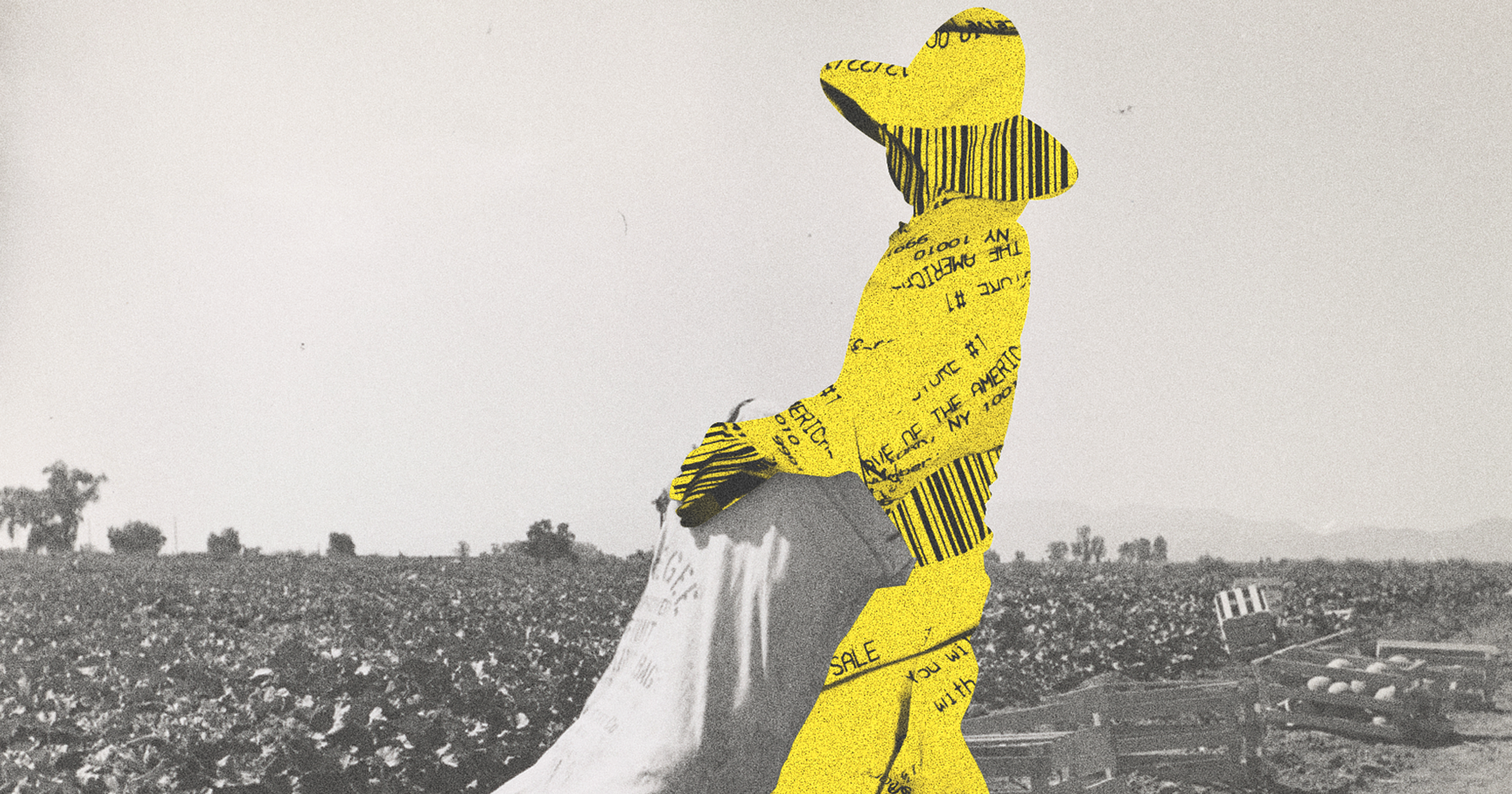

Legislation penalizing companies that employ undocumented workers goes into effect on July 1. Some farmworkers, fearing discrimination and deportation, are already fleeing the state.

In fields across Florida, ripe tomatoes, lettuces, and strawberries are rotting away under the sun’s relentless glare. Around the state, untold numbers of farmworkers have stopped showing up for work, fearing discrimination and deportation in the wake of a new state law that aims to crack down on illegal immigration.

The legislation (Senate Bill 1718), signed by Governor Ron DeSantis on May 10, makes it illegal to transport undocumented people across state lines. It requires hospitals to collect data on a patient’s immigration status and submit quarterly reports to the state agency that administers Medicare. It voids out-of-state driver’s licenses for those without proof of citizenship. And, perhaps most significantly, it requires companies with 25 or more employees to verify worker citizenship status through the federal E-Verify system, which is operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security — something that agricultural employers have been exempt from in the past. Now, if anyone hires a worker who is considered an unauthorized alien, they could face penalties of up to $1,000 per day.

Two weeks after signing the bill, DeSantis announced he was running for president, with curbing illegal immigration a centerpiece of his campaign.

While the law doesn’t take effect until July 1, its repercussions are already being felt — including by those who supported the bill. “I’m a farmer and the farmers are mad as hell,” Republican state representative Rick Roth, who voted in favor of the anti-immigrant bill, told the crowd at a recent event. Roth all but begged workers to not leave Florida: “We are losing employees. They’re already starting to move to Georgia and other states.”

Florida is home to an estimated 772,000 undocumented workers, who play a vital role in the state’s agriculture, construction, hospitality, and transportation industries. It’s estimated that noncitizen immigrants account for somewhere between 37% and 47% of Florida’s agricultural workforce. Last Thursday, some of those immigrant workers and their supporters held a day-long strike throughout Florida to protest the new law.

Neza Xiuhtecutli, director of the Farmworker Association of Florida, estimates that there are about 300,000 farmworkers who live in the state illegally. Immigrants “are all over the agricultural industry,” he said. “We employ primarily farmworkers from other parts of the world, and not just Hispanic, but also Haitian and Jamaican farmworkers.”

The law is expected to have a cascading effect on the Florida food system. “If nothing changes, there will most certainly be sharp decreases in production affecting not only farmers and farmworkers, but the rural communities in which we operate who depend on agriculture,” said Adam Lytch, regional manager at L&M Farms in East Palatka, Florida. Lytch highlighted the important role skilled foreign workers play in American agriculture during his testimony at a recent Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing.

“I’m a farmer and the farmers are mad as hell.”

Many expect to see the number of temporary H-2A workers increase as a result of the legislation. The H-2A guestworker program allows farmowners to — legally — bring nonimmigrant foreign workers to the U.S. to perform temporary agricultural labor. While migrant workers have the opportunity to earn more than they could in their home countries, it requires them to leave their family for long periods of time. While working in the U.S., they rely on their employers to provide housing; many are housed in temporary labor camps.

As domestic workers have found jobs outside agriculture, the H-2A program has grown rapidly in recent years. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Labor certified around 370,000 H-2A workers — more than seven times the number certified in 2005, and double the amount in 2016.

Xiuhtecutli is worried that a further increase in H-2A workers in Florida will lead to significant steps backwards for farmworkers’ rights. “It puts workers in a very vulnerable position because they depend on their employers for food, transportation and housing, and isolates them from the outside world,” he said. “So they have little chance of actually learning about their rights … what they can expect and what the law protects them from.”

Furthermore, it “would displace workers who are already here,” said Xiuhtecutli. “They know the system, they’re climatized, they’re skilled in local agricultural work.”

“There will most certainly be sharp decreases in production affecting not only farmers and farmworkers, but the rural communities in which we operate.“

Under the new law, farms are out to lose, too. After Georgia passed its E-Verify law in 2011, sixth-generation blackberry farmer Gary Paulk witnessed 300 farmworkers flee, which he expected would force him to “abandon about 25 percent of his 125 acres,” accounting for “a projected loss of $250,000” that year. According to an estimate from the Florida Policy Institute, this new employment verification mandate could cost Florida’s economy $12.6 billion in one year.

“It costs a lot of money and it doesn’t really make you any more. It just allows you to play the game … It’s burdensome on the growers,” said Gene McAvoy, a former extension agent who now consults with growers across southeast Florida. “When I started working with growers in South Florida 27 years ago as an extension person, I answered technical questions related to growing — fertilizers, what to do about insects. The past couple years, my job has really transitioned to helping farmers comply with all [these regulations].”

How agricultural operations will look under the new law is still unclear. “Everybody’s taking a deep breath. We’ll really start to see the impact next month in mid-July when it’s time to prepare land and then start planting in August. That’s when we’re gonna see what’s what,” said McAvoy, who compared his expectation to the plot of the controversial 2004 film “A Day Without a Mexican,” in which all of California’s Latino residents mysteriously disappear, and leave “rich people in Beverly Hills trying to cut their own lawn and make their beds.”

For undocumented Florida farmworkers, however, the threat is here — and it’s real. “We’re already seeing the effects now. People are already afraid for the future of their families … people are already being discriminated against,” said Xiuhtecutli. “It’s not about what we can expect when the bill is implemented. It’s already happening.”