Small producers rarely manage to access USDA grants and loans. Independent consultants may boost their odds of “winning.”

Spend enough time with farmers and you’re likely to hear a number of recurring gripes: about, say, the heavy burden of government regulations, or non-farmers’ failure to understand agriculture’s challenges. Among small farmers and ranchers, who are often struggling to operate on the slimmest of margins, a dearth of federal monetary support — despite billions of dollars available from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) — is at the top of the gripe list.

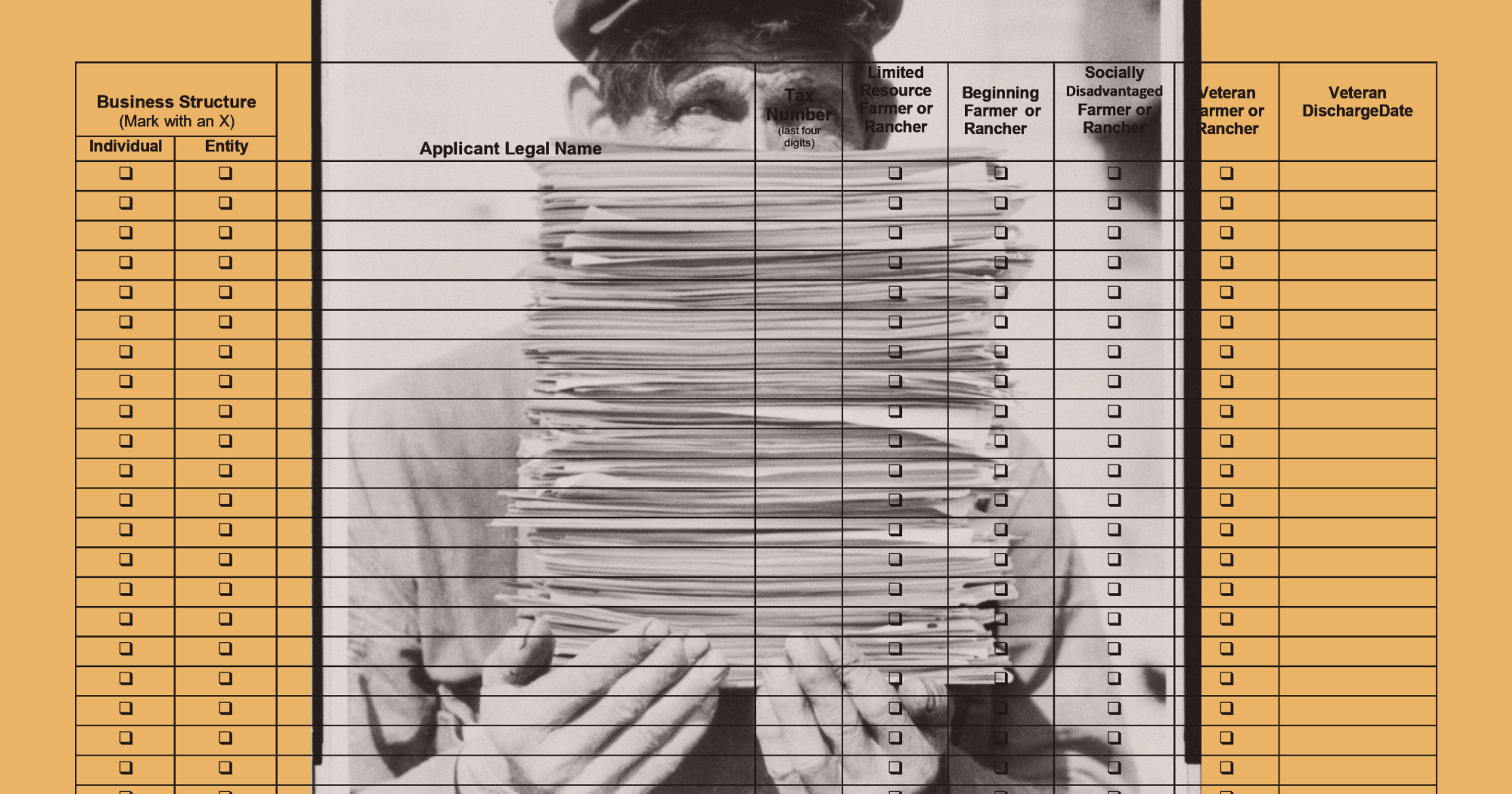

In theory, small producers are eligible for at least some of that USDA money. But in practice, say experts, they’re greatly disincentivized by the application process. Those who do figure out how to wade through what can be 100-plus pages of paperwork often report being denied for reasons they don’t understand. As a result, some turn to independent consultants for help. Consultants can’t guarantee funding “wins,” but in some instances they might increase the odds of a windfall.

To its credit, similar to the IRS trying out ways to help Americans file taxes for free, USDA has recently attempted to elucidate the process of applying for loans, grants, disaster assistance, and the like, particularly for “historically underserved” farmers and ranchers. A 2022 Get Started guide offers essential information. It outlines what money is available for what practices and emergency scenarios; who qualifies for it; and where to start trying to access it — namely, by visiting one of several thousand local USDA service centers (there’s one in every county) that offer free guidance.

It sounds simple. The reality is a lot less so.

The local service centers tasked with helping farmers parse the USDA funding landscape are not all created equal. Some of them have grazing or agroforestry or energy experts on staff who can assist with the plans necessary to support an application; some don’t. And that’s just the start of the challenges.

Applying for money is “a networking game. If your USDA rep knows you, you’ll be more plugged in and likely to get funding,” claimed one producer on the website of a farmer-funding app called FarmRaise. (USDA did not respond to requests for information or comment in time for this article to run.) And who’s winning that game?

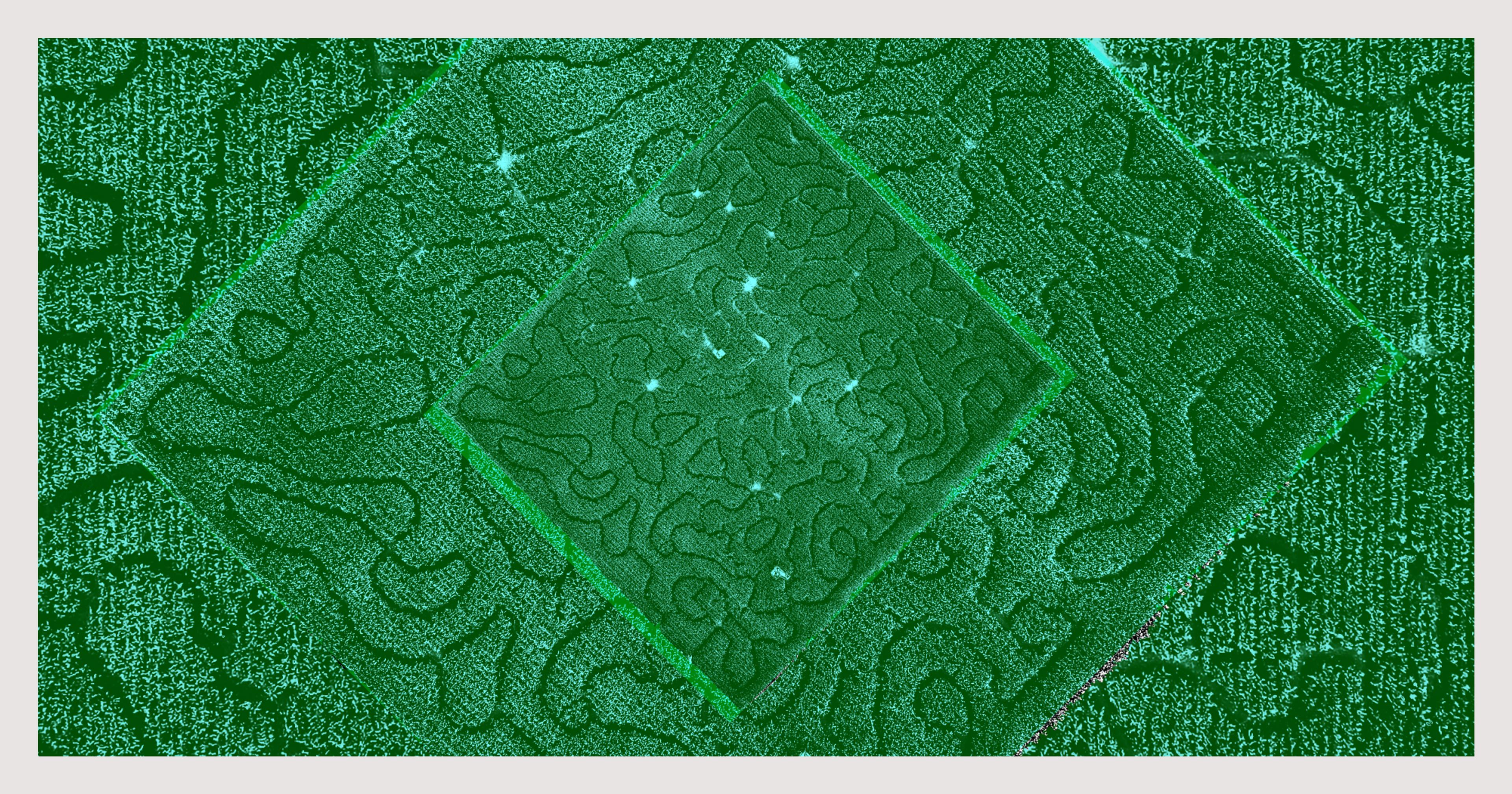

A 2022 report from the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy showed that larger, industrial farms receive the majority of particularly conservation program funding. Said Ryan Nebeker, a research and policy analyst at non-profit food advocacy publication FoodPrint, “There’s a strong institutional bias towards helping larger farms first. The thinking there is that small changes on your biggest operations will go the furthest when money is limited.”

Ambrook, the parent company of this publication, started helping farmers apply for USDA money a few years back, by developing software that automatically filled in portions of forms — and there can be a lot of these, especially for first-time grant-seekers. This simplified applications for the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), which didn’t require business plans or tax forms or on-site audits. But most USDA applications are significantly more complicated and arduous, prompting Ambrook to focus its next efforts on building tools that would enable farms to have stronger financial records in order to better apply for funding.

“There’s a strong institutional bias towards helping larger farms first.”

Outside involvement in the grant application process seems to raise the hackles of some USDA county office staffers, even though there’s nothing strictly illicit about it. In addition, say industry insiders, USDA prioritizes farmers who’ve gotten big grants before, because they’ve proven they are good stewards of USDA money.

Matt Wilson is technical service program manager at agroforestry nonprofit Savanna Institute. He said staffers at USDA service centers “have a good handle” on what pots of money are available for cropland, wildlife, and pasture plans, and so on. That said, they may not always be aware of what practices are eligible to receive this money — another reason farmers might reach out to independent consultants.

“If you go into a [Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS] office in corn and bean country, they’re going to be really familiar with cover cropping and crop rotation, which they work with large producers on,” he said. “If you say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a market garden operation,’ or ‘I want to do agroforestry,’ they might go, ‘We don’t have anything available for that’ — even though technically those things are available. [There can be] unfamiliarity at the local office and it changes every time the Farm Bill gets updated. A big part of our job is just helping NRCS staff get up to speed on what’s available.”

NRCS runs many programs that are the source of USDA money small farmers are eligible for — at least on paper. It may create plans — for pasture management, forest management, and transitioning to organics, for example — that provide the framework for the application a local center files on behalf of a farmer. If there’s no existing management plan, such as for agroforestry practices in Wisconsin, a local office might contract with a technical service provider (TSP) like Wilson to help develop one for a farm’s very specific needs (again, at no cost to the farmer). If an application is approved, a TSP is needed to help a farmer implement her plan; the NRCS office pays the farmer 75% to 90% of this fee to then pay the TSP.

TSPs like Wilson are in short supply around the country, though, because they often need specialized backgrounds and training to qualify and Wilson said the process is complex — even if you do have the right training. In Wisconsin where he works, “We have more demand than we can service.” This has led to a backlog when “there’s definitely a growing need” for more people to help farmers with applications, said Juan Whiting, an independent consultant hired by farmers to both identify potential funding opportunities and write applications. The process, he said, “is a lot of work — the equivalent of writing a dissertation. There are a lot of people that are like, ‘I’m gonna do it on my own,’ and I’m like, ‘Do it on your own and you’ll never do it again.’”

“There are a lot of people that are like, ‘I’m gonna do it on my own,’ and I’m like, ‘Do it on your own and you’ll never do it again.’”

Whiting prefers to work with larger producers or organizations, since an application for a $20,000 loan is just as much work as one for $2 million, he said. This highlights another way smaller farmers are disincentivized, whether they’re approaching paid consultants or USDA staffers and TSPs. Said FoodPrint’s Nebeker, this agency-wide staffing crisis means that helping a smaller farmer access a smaller grant looks “really time-consuming and ineffective per hour of staff time. Unless you have staffers who are really passionate about helping small farms, they’re probably just not a priority.”

Still, if a farmer can find a consultant to help either for an up-front fee or a percentage of an eventual win, the expense may be worth it. According to FarmRaise, small farmers may be unaware that USDA has an application ranking system that it uses to determine whether or not to fund, and the system is hard to crack if you’re not an expert. Furthermore, USDA websites might contain out-of-date information; funding cycles can be short and farmers late to finding out about them; and individual USDA service centers often have different requirements for how paperwork needs to be filled out and filed. A consultant who is constantly researching and assessing USDA’s funding availability and parameters likely has a better grasp on how to make a farm look worthy of a grant or loan, and what the timeline is.

Janet Everly runs a grant-writing and consulting business in Indiana with her husband, Bruce, who’s also a TSP specializing in energy audits for seekers of REAP grants to improve energy efficiency. Janet said the company has a 92% success rate in helping their clients, including farmers, secure these grants to partially reimburse the cost of things like grain dryers and solar panels.

Any producer with a project over $10,000 is welcome to apply for a REAP grant but an application “can easily be 150 pages. We’ve had some that were almost 400 pages,” Everly said. “The application process is complicated and it took us many years to provide a product that is consistently good. We like to think that having a consistent product makes it easier for the USDA to navigate and score the application, which can take them many hours to process.”

Regardless, Everly said there are limits to how much even their decade-plus of expertise can translate into improved outcomes for farmers. USDA “changed the program recently and there’s a whole lot more competition; it used to [reimburse] 25%, now they’ve bumped up to 50%,” she said. “We really don’t know what our odds are this year.”