Analysts say proactive responses by farmers may bring costs down.

Climate change has cost the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) billions of dollars in federal crop insurance payouts to farmers over the past decades, according to several recent studies.

What is difficult to determine, however, is how much farmers will have to pay in the future for higher farm insurance policy premiums due to climate change impacts from phenomena such as severe storms, rising average temperatures, and extremes in precipitation.

Some experts do say there will be an increase in the cost of farm insurance premiums, but determining the premiums for the federal crop insurance program (FCIP) involves multiple complex variables, including climatic conditions, crop yield performance history, and other factors. These premiums aren’t borne by farmers alone — taxpayers subsidize crop insurance premiums by a little over 60% on average, according to the USDA.

Climate change comes at a significant cost to farmers and taxpayers alike, according to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. A January EWG report shows that U.S. farmers received more than $143 billion in federal crop insurance payouts from 1995 through 2020. Drought and excess moisture, which EWG says are exacerbated by climate change, accounted for more than 61% of all crop insurance payments – referred to as indemnities – during that period, according to the group. Payments for drought skyrocketed 400% between 1995 and 2020, while payments for excess moisture increased almost 300% during that time period, though some of those spikes were due to other factors, such as increases in the value of crops and more acreage planted.

“Climate change is already having an impact on the crop insurance program.“

“Climate change is already having an impact on the crop insurance program. This is something that is just going to increase costs in the future, and it is very likely increasing costs already,” according to Anne Schechinger, EWG’s Midwest director and agricultural economist, who authored the analysis.

Schechinger said that climate change also is very likely to increase the costs of the crop insurance program to farmers, because farmers pay about 40% of their crop insurance premiums on average. “When premiums go up because of increased risks from climate change, then we know the farmer payment part of the premium will also go up,” she said.

An August 2021 Stanford University study found that “global warming that has already occurred has contributed substantially to rising crop insurance losses in the U.S.” The study, which analyzed the cost of the crop insurance program from losses (but did not look at the cost of the crop insurance program to farmers), found that higher temperatures attributed to climate change increased payments from the federal crop insurance program by $27 billion between 1991 and 2017, and contributed nearly half of the $18.6 billion losses in 2012 alone. Global warming contributed 19% of the cumulative national-level crop indemnities of $140.5 billion during that period, according to the report.

“Our results strongly suggest that global warming is already causing financial costs,” said the study’s lead author, Noah Diffenbaugh, professor of Earth System Science at Stanford. Even so, Diffenbaugh said that the increases in total indemnities over that time period are much larger than those caused by global warming, and that it would be inaccurate to claim global warming was the primary cause of the overall increases.

“We can be confident that additional warming, all else being equal, will cause those [premium] costs to rise,” he said. Extreme years climatically have a much bigger contribution to crop payouts, he said, adding, that “the odds of there being more extreme years is going up as a result of global warming.”

“The odds of there being more extreme years is going up as a result of global warming.”

Joseph Glauber, senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, agrees that climate change has driven up indemnity payments to agriculture. “There is no question that climate change will increase. To the degree that it affects yield variability, it will have an impact on rates, which are the underlying premium costs for farmers. Those rates will go up,” he said. But he also said that many factors have made crop insurance more expensive.

Because the crop insurance program is so heavily subsidized, farmers will only feel a portion of any increase, said Glauber, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and former chair of the board of directors of the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation.

Glauber said that although the process of setting crop insurance rates is arcane and slow, USDA’s Risk Management Agency, which manages the crop insurance program, constantly reviews and revises rates to adjust for changes that are occurring. Climate change impacts on yield variability will ultimately be reflected in crop insurance rates, he said. However, these could be gradual rate increases because the agency looks at several years’ worth of data, Glauber added.

Glauber said the crop insurance program’s premiums have been sufficient to cover the indemnities. “The program has been on an actuarial sound basis for 20 years now,” he said. “The rating methodology works pretty well.”

Crop insurance incorporates changing risks over time to charge producers actuarially fair premiums, according to a USDA spokesperson in the department’s Farm Production and Conservation Mission Area. “Risks from climate change, and any other factors, are automatically incorporated as part of normal program maintenance. This helps the program adapt to locations, crops, and practices that are more or less vulnerable to climate impacts in a fair manner,” the spokesperson said.

“Risks from climate change, and any other factors, are automatically incorporated as part of normal program maintenance.”

The USDA spokesperson said farmers may encounter higher costs from rising climate-risk-related farm insurance prices, depending on their individual circumstances. “Some producers may have lower insurance premiums due to minimal climate risk but strong technological innovation reducing risks. Others may have the opposite effect. Since the premium reflects all changing risk factors, not simply climate change, there will likely be significant variation across the program and over time,” according to the spokesperson.

A 2019 USDA report indicated that climate change could affect the federal government’s fiscal exposure from the FCIP, “as premiums and subsidies adjust with changing growing conditions. Adverse weather could make yields more variable from year to year, causing losses to happen more frequently.”

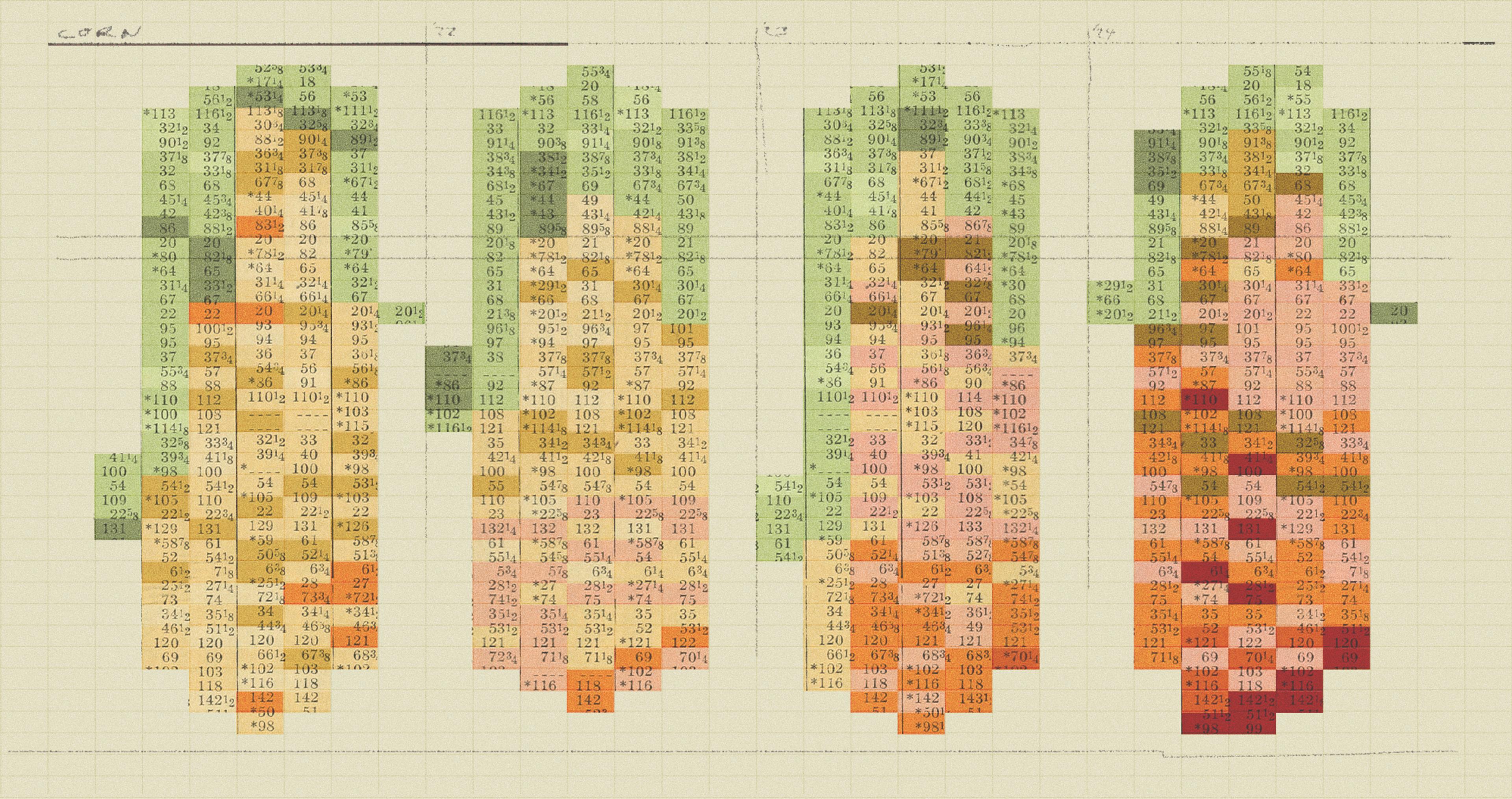

A recent report by the risk modeling company Verisk indicates that simulated yields across the U.S. Corn Belt between 2046-2055 were 20-40% less than yields simulated between 1991-2000 due to the impact of climate change on weather. The overall modeled corn response to global climate model-projected climate change over the period 1991–2055, averaged across the four GCMs over the entire Corn Belt “was a reduction in yield of about 7% per °C summer warming in the Corn Belt,” according to the report.

However, determining changes to insurance premiums “is a multi-dimensional problem,” said Julia Borman, manager of the regulatory and rating agency client team at Verisk, and an author of the report. For instance, she said lower yields could move crop prices higher. “When yields go down and prices go up, then your actual revenue can be quite close to your expected revenue, and you won’t necessarily trigger your [insurance] policy,” she said.

“When yields go down and prices go up, then your actual revenue can be quite close to your expected revenue, and you won’t necessarily trigger your [insurance] policy.”

Eric Belasco, associate professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics at Montana State University, Bozeman, noted another challenge to making linear projections: farmers are constantly modifying their behaviors and often invest in technologies that could help to mitigate climate impacts.

Joe Glauber summed up the question about insurance costs to farmers. “The basic story is that with climate change you are going to have higher premium costs. That means a higher cost to farmers,” he said. It also means “a higher cost to the government in the sense that they subsidize insurance costs.”