The U.S. is losing farmers year over year, but one demographic is growing — despite significant challenges.

According to the USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, Asian-operated farms increased by 6% between 2017 and 2022, even as the total number of U.S. farmers declined. Despite comprising only 0.8% of the country’s 3.4 million producers, their growing presence isn’t going unnoticed.

Several factors may have contributed to this increase. There were a few notable demographic shifts — the average age of Asian producers is 54.6 years, about four years younger than the overall U.S. producer at 58.1 years. Also 47% of Asian farmers were beginners as compared to 36% overall. This matches anecdotal evidence of the growth of farms launched by young Asian American women in recent years.

This rise in Asian American farmers also coincides with shifting consumer preferences, as nearly half (47%) of Asian producers focus on specialty crops. Between April 2023 and April 2024, retail sales in the U.S. “Asian/ethnic aisle” and produce sections — think sugarcane, bittermelon, and water spinach — grew nearly four times faster than overall grocery sales. This dovetails with the fact that Asians are America’s fastest-growing ethnic group. However, Asian grocers such as Korean grocer H Mart — now valued as a company at two billion dollars and including over 100 stores across 18 states — report that its customer base is at least 20% non-Asian. In response, some Asian American farmers are blending ancestral farming methods with modern sustainable techniques to meet this evolving demand.

“I came to farming on my own through a long and circuitous path,” explained Kellee Matsushita-Tseng, founder of Bitter Cotyledons, a group of cultural workers/artists centering, archiving, and sharing the stories of queer Asian American Pacific Islander community through the lens of ancestral foodways. She strives to bring culturally significant foods to underserved communities.

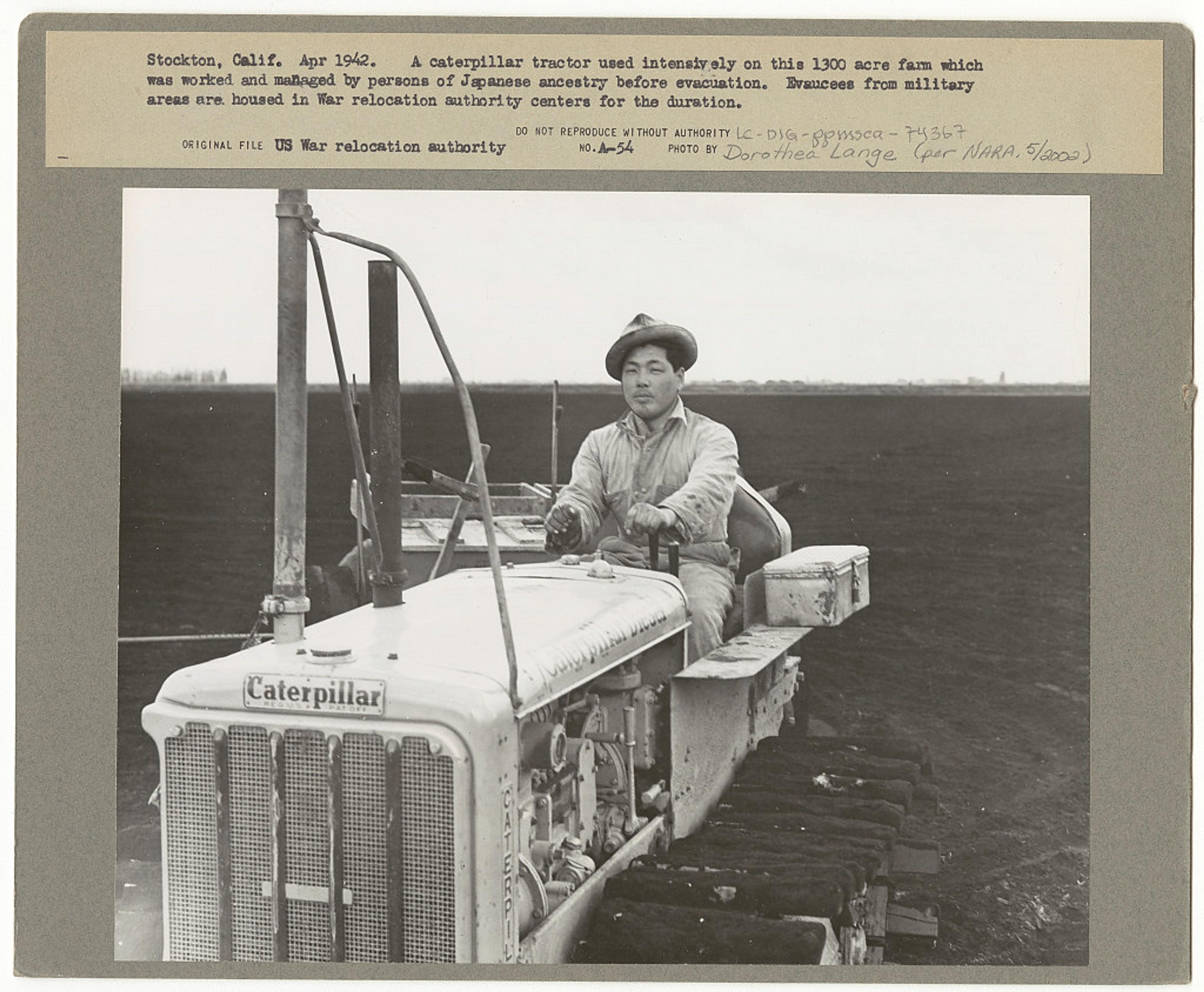

In California and Hawaii, where Asian American farmers are concentrated, cultural heritage often informs crop selection and farming methods. “My grandfather, a second-generation Japanese American, grew up farming in Stockton, California,” said Jade Sato of Minoru Farm. “During World War II, our family’s land was confiscated when they were interned in Japanese incarceration camps. It wasn’t until after his death that I realized how much I missed connecting to the earth and working with the soil.”

A farmer of Japanese ancestry in Stockton, California, in April 1942, prior to evacuation

In New York’s Hudson Valley, Christina Chan of the farm Choy Division started Choy Commons, a collective of Asian American farmers growing ancestral foods to distribute to local and often disadvantaged communities. She finds that growing sustainable Asian vegetables helps bridge the gap between her American upbringing and Chinese heritage.

“Early in my farming career, I explored Korean natural farming,” said Sato, who farms in Adams, Colorado. “There are also many similarities with subsistence farming, which is common in China. I studied how Asian people in different climates work with the land in a way that reduces waste and considers the full cycle of life.”

The legacy of traditional practices is also evident in Hmong-built farming communities in Minnesota. After arriving in the U.S. as refugees following the 1970s Khmer Rouge genocide, these farmers have become essential to local agriculture, now comprising more than half of Minneapolis and Saint Paul farmers. There’s also a significant population of Hmong farmers in Fresno, growing much of California’s Central Valley’s strawberries, ginger, and sugarcane.

Overcoming Challenges

Systemic barriers have historically prevented Asian Americans from thriving in agriculture. Before World War II, two-thirds of West Coast Japanese Americans worked in agriculture, producing 40% of commercial vegetables in California. The mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war led to seizures of their land and property, an event from which most never recovered. Earlier, discriminatory policies like the California Alien Land Law of 1913 prevented Asian immigrants from securing long-term land leases or ownership. Organizations like the Asiatic Exclusion League further marginalized Asian farmers and laborers.

More recent laws in at least two dozen states forbid foreign-born individuals or entities from owning farmland — and specifically target China. National security is the professed reasoning behind the laws even though Canadians represent the largest portion of foreign landowners at 33%; Chinese holdings are less than one percent. Activists argue that these laws are on pace with past discriminatory laws against Asian Americans in the United States, and do not bode well for the future.

Many Asian American farmers also still face structural challenges, including difficulties in securing funding and land ownership. “Getting funding when you’re a small farm is tough,” said Sato, whose farm encompasses nine acres and focuses on growing Asian varieties of produce. “We’ve tried to get USDA funding, but I have limited time to write detailed proposals about how I’d use the money if I got it.” These are similar challenges faced by Black and Latino farmers who have faced a history of discriminatory laws and USDA practices.

On top of these hurdles, it’s no secret that farming is a tough livelihood for all producers. “It’s more than just putting a seed in the dirt, adding water, and harvesting,” said Noah Hubbard, a row crop farmer in Central Nebraska who goes by The Korean Korn Farmer on TikTok. “Depression and suicide rates in agriculture are incredibly high. I have a farmer friend down the road who recently took his own life. It’s emotionally taxing work.”

Choy Division

Climate change further complicates an already unpredictable profession. “Two years ago, I returned from the farmer’s market on a Saturday, and it was a beautiful day,” said Sato. “I go inside to unpack, and this huge storm rolls in with tornado gust winds up to 80 miles an hour. It completely ripped apart our field, and our greenhouse was utterly destroyed in ten minutes. It took an entire year and a half to rebuild and recover.”

Yet, despite hardships both specific and general, Asian American farmers have long contributed to U.S. agriculture. “Many early 19th-century Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrants arrived with farming experience,” said former USDA Equity Commission Member Yvonne Lee. “In California, they pioneered and created the asparagus, celery, and strawberry industries.” She also points to the enormously popular Bing Cherry, developed by Ah Bing in Oregon in the late 1800s.

“Supporting these farmers means using consumer power to uplift this still invisible yet vital group in the American food chain,” said Lee.

Community organizations and advocacy groups are crucial in this movement, providing resources, policy advocacy, and community-building efforts. “The agricultural system is changing, and there are ways to build businesses and farms that focus more on relationships than commodities,” said Matsushita-Tseng. “There’s starting to be a shift in public awareness about supporting historically disadvantaged farmers, which will be the key to success.”