Sowing novel mixtures of wheat, barley, and rye could offer farmers a hedge against climate unpredictability.

Picture a small field of dry, rocky soil, dotted with workers. They’re busy hand-scattering a mixture of seeds throughout, without regard for the neat rows of single grains that are emblematic of modern agriculture. The farmworkers’ movements look casual, almost haphazard, but in fact are quite deliberate. At a time in agriculture when envisioning the future may mean looking to the past, a forgotten method of farming may provide some solutions to climate change’s many challenges.

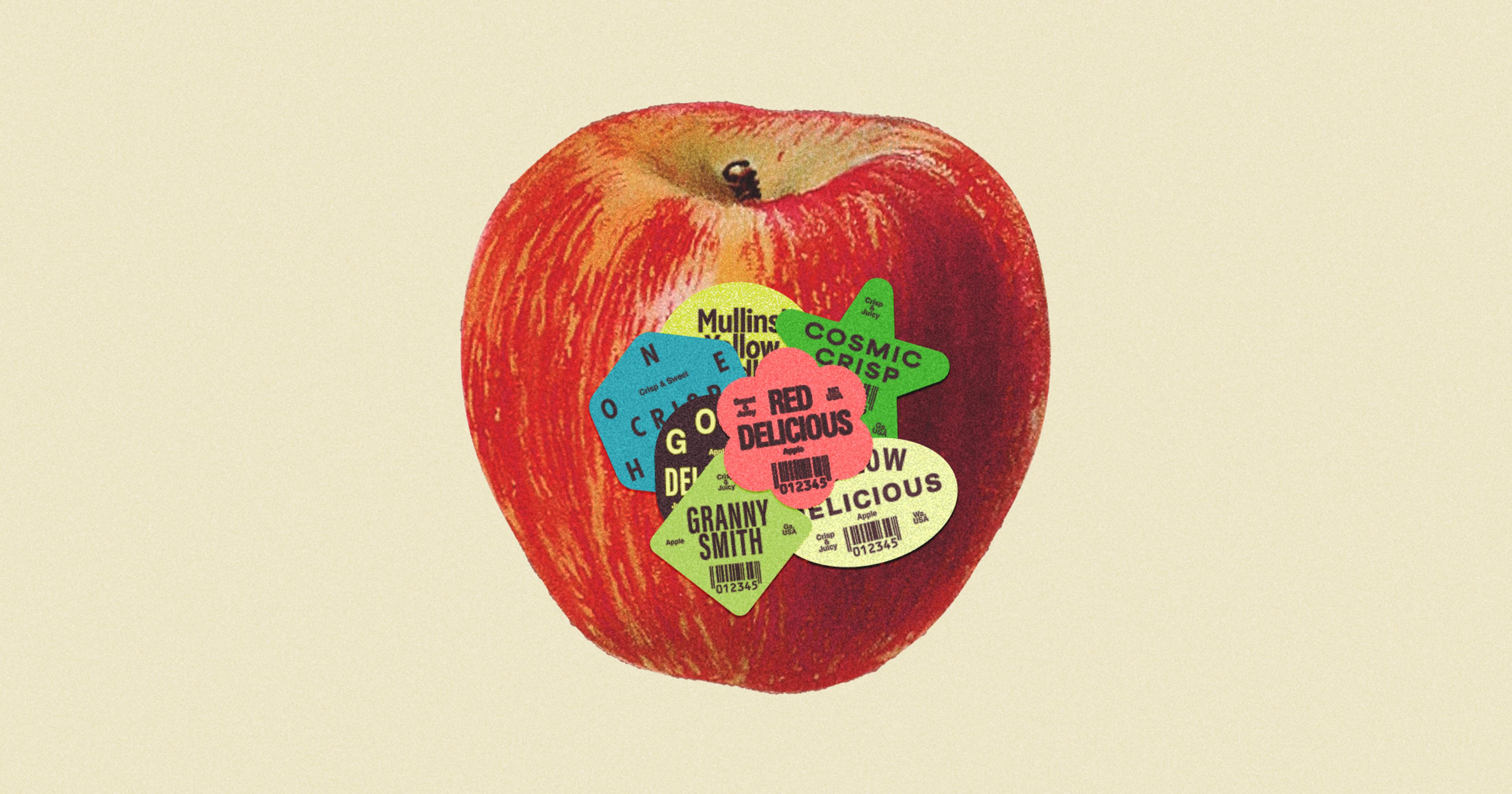

Maslins are both a method of planting and a cereal species mixture that can include the seeds of wheat, barley, rye, and other grains. In this seemingly unconventional ancient practice, a mixture of those seeds are hand-broadcast throughout a field. Sowing maslins fell out of fashion with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, as mechanized equipment and standardized farming methods transformed global agriculture to produce more uniform commodities.

Yet in countries like Ethiopia and Greece, some smallholders are still farming as their forebears did, sowing maslins into soil of varying conditions. No matter how wet or dry the growing season, those farmers are almost always able to produce grain, ensuring they can feed themselves and their families. Maslins use light and soil more efficiently than a single crop does, taking advantage of nutrients, light, and water at different times. For example, barley uses sunshine earlier in the season and wheat later on.

That’s why maslins are of particular interest to researchers, intrigued by the possibility that their risk tolerance and unique adaptability can be used by modern-day farmers as bulwarks against climate change.

Maslins are perhaps the original state of grain crops, said Alex McAlvay, the Kate E. Tode assistant curator of the Institute of Economic Botany at the New York Botanical Garden. “If you go to the Fertile Crescent and look at wild wheat, you rarely find it without wild barley,” he said. “It’s co-evolved for tens, hundreds, or thousands of years together in the wild. When people domesticated them, it’s no surprise they are somewhat compatible with each other and tend to co-occur.” It actually takes work to keep them separate, he added, because barley will invade a wheat field if you’re not careful.

McAlvay broadly defines maslins as any mixture of a small cereal or small grain. He learned of them when he was still a student in 2011, on a research trip to Ethiopia with fellow post-doc and graduate students .

Maslins are unlike the most familiar Western polyculture, growing different crops like corn, squash, and beans together — known as the Three Sisters method — said Alison Power, a professor in Cornell University’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. She studies insects and diseases and how they are buffered by certain types of cropping systems.

The students who visited Ethiopia had been conducting research in Power’s lab. She said most people working in the agroecology field in the U.S. are not aware of the practice, but that the historically common system makes sense. “Under the expectation of climate change and unpredictability of moisture regimes, having the two mix together in a field offers some true advantages,” Power said. The grains have some complementary characteristics, like different depths of roots due to differences in drought and waterlogging tolerance. And different crops have varying needs for soil depths or nutrients, which allows them to coexist.

A mixed field of over 100 spelt and emmer wheat varieties

·Photo provided by John Letts

Ethiopian farmers said they preferred the taste and texture of the mixed grains, that they are more resistant to fungal diseases — specifically rusts — and are more drought-tolerant. Wheat and barley mixtures were the most widespread. Farmers in the country of Georgia have made similar observations, despite the two countries’ considerable climate and cultural differences.

Spurred to investigate further, McAlvay and colleagues published a lit review last year, consolidating agronomic and cultural information, including an intriguing fact that during the Ottoman Empire, taxes of mixed crops of wheat and barley were extracted from Serbia and Croatia. Current research projects include farmer interviews and field experiments in Ethiopia to learn more about insect and fungal resistance; drought-tolerance; productivity and yield stability; and the possible nutritional benefits of these staple crops.

McAlvay is also in the midst of a three-year experiment with Georgia’s Scientific-Research Center of Agriculture, its equivalent of the USDA, testing mixtures to potentially reintroduce to farmers there. Georgia was once the world’s epicenter for maslins, said McAlvay, as well as the center of wheat diversity, but the practice is no longer used there.

A third initiative, in Lebanon, where wild wheat still grows with wild barley, is in early stages, exploring how the relatives of these crops have co-evolved. Also on the agenda: how the components’ complementarity can improve yield, and how the mixtures adapt.

“The adaptation piece is even less studied and a unique feature of variety mixtures and maslins,” said McAlvay. One year’s environment influences the proportions planted in the next year. If more barley is harvested one year and that seed is saved and proportions not readjusted, more barley will be planted the next year. But if there is a gradual climate change, like getting a little drier, mixtures might track that change without a farmer having to intentionally adjust proportions.

“To me, conventional farming is no longer possible.”

It’s unclear why a mixture would not revert to a monoculture, but McAlvay said maslins seem to be self-balancing. Power doesn’t think reverting to a monoculture will occur in the short term because of weather anomalies, but doesn’t rule out the possibility; no experiments have yet been done to prove it.

Another important element is how one grain compensates for the other. When wheat has a poor growing season, perhaps because of a drought, the barley will grow well, and vice versa. It’s still in the early days of understanding the mechanism for these and other benefits, said McAlvay.

Early research offers promising information regarding disease resistance and tolerance. Unable to travel to Ethiopia in 2020, Anna DiPaola, a graduate student in Power’s lab, conducted an experiment at Cornell’s research farm in Freeville, New York. Her research established proof of concept that planting maslins in comparison to monocultures has an effect on aphid behavior and subsequent barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) spread. One of the mixtures did not get infected the same way that one of the monocultures got infected. The identity of the varieties planted also really matters, said DiPaola, who will submit her results for publication this fall.

While the concept of maslins came as new information to McAlvay and others, John Letts in Oxford, England, said he’s a black sheep who has been growing grain mixtures for over 25 years.

Letts is by training a paleo ethnobotanist, someone who studies human uses of plants through time. He began farming with grain mixtures to recreate the genetic diversity of the past, growing crops as they were produced in the Neolithic period using a low-carbon approach. Using no inputs, he said he is mimicking a natural grass ecosystem to foster and promote a sustainable way of farming.

“To me, conventional farming is no longer possible,” said Letts. “We have a lot of mouths to feed, but if we keep doing it this way, we’re all gonna die. Somewhere along the line, we’ve got to use science, our brains, justice, and equality at an economic level to feed everybody.”

“You need a sustainable solution. That’s got to be about genetic diversity, resilience, low input, carbon sequestration, feeding the soil biome.”

Letts’ eureka moment came when he was gifted a box of medieval thatch, dried grasses that were mixtures of ancient grains used to create roofs of buildings hundreds of years ago. It led him to develop what he considers true landrace grains using his find and thousands of seeds obtained from gene banks. Letts said in England, maslins are called mixtures or populations, and are strictly mixtures of wheat and rye.

His mixtures are resilient, genetically diverse, don’t require chemicals for disease prevention, and access moisture from different soil depths depending on the grain. Each plant’s unique differences pull together, acting as a buffer against environmental pressures.

For Letts, growing mixtures can reduce yearly yield because he doesn’t use chemical fertilizers. However, Letts said his yield is up to three times that of an organic system. He grows in the same field every year, planting clover as a cover crop to fix nitrogen in the soil and foster a “funky mycorrhiza,” he said, to support the plants. His goal is to obtain the system’s highest yield, not that of the annual crop.

Now focused on plant breeding, Letts oversees the select farmers growing his mixtures for his company, Heritage Harvest, which sells flour to bakers and soon to consumers. He is also executive director and head of farming and sustainability for the award-winning spirits at Oxford Artisan Distillery.

Liquor behemoth Diageo, which owns brands including Johnnie Walker and Tanqueray, recently made a minority investment in Oxford for Letts to conduct R&D in sustainable grain growing for the distillery.

With Diageo’s global reach and his ability to create new grain populations, Letts is hoping to play a role in transforming cereal production. Ultimately, he said, “I want to feed people.”

Letts ignored colleagues who said mixtures were not the future of farming. “You need a sustainable solution. That’s got to be about genetic diversity, resilience, low input, carbon sequestration, feeding the soil biome,” he said. “How do you do that in cereals? This is the best system I can figure out.”