The creator of Stardew Valley discusses whether video games can work as young farmer recruitment tools.

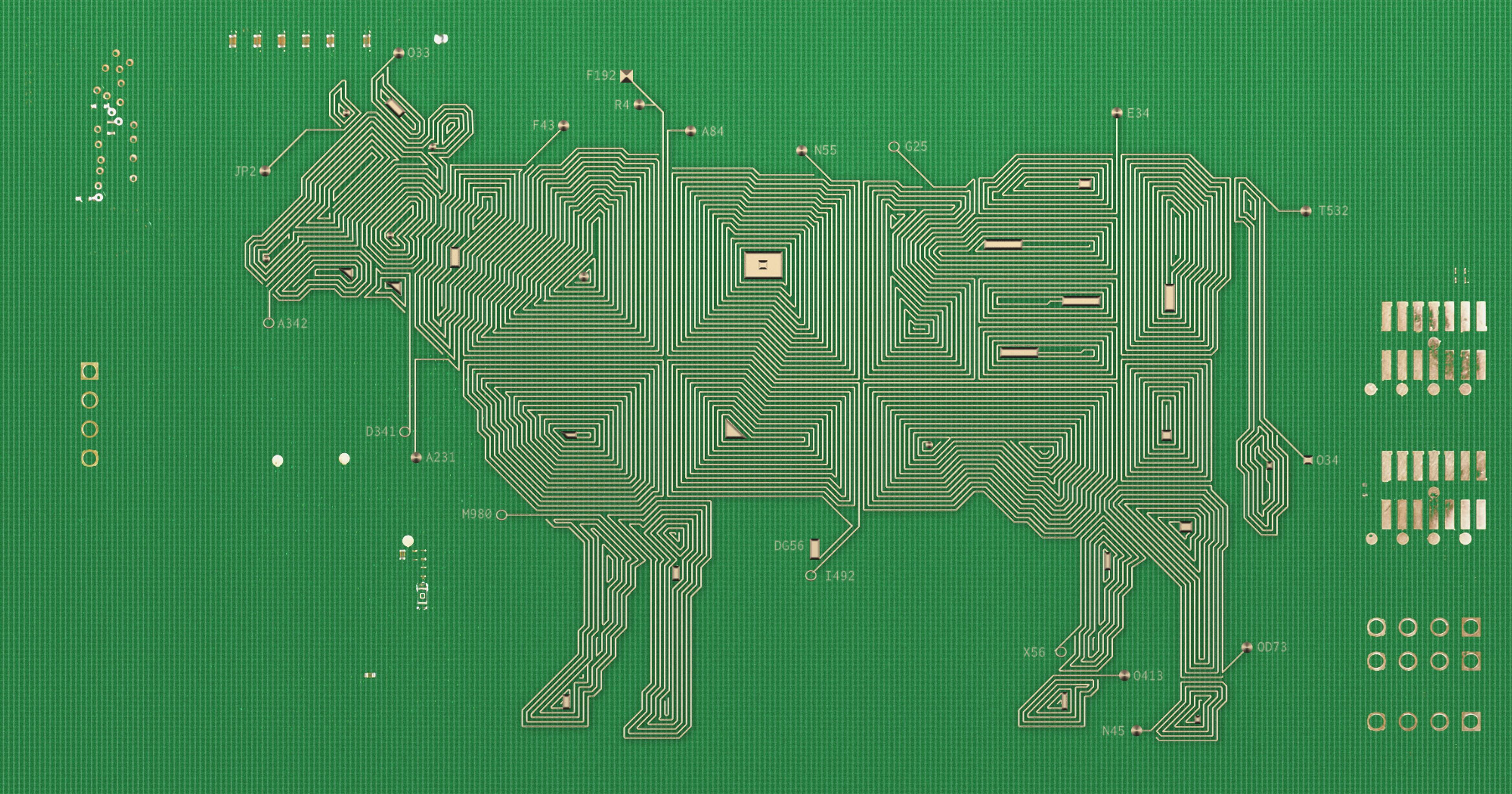

Flight simulators that prevent real plane crashes. Building a virtual hotel that redirects to a hospitality job application. Digital games have concrete, tangible value for certain industries. Take the U.S. military, which has been using games like Fortnite to target new generations of tech-savvy gamers in its efforts to recruit more young people into service. The NYPD is using a VR game to inspire city residents to make better public safety choices by placing them into virtual situations on the street. Gamification is becoming one of the most popular recruitment tools real world industries have to synthesize the digital zeitgeist today.

But when it comes to the farming industry, can digital games like Farming Simulator or Stardew Valley crack the code on recruiting new farmers?

Less than 8% of the American farm workforce is under the age of 35, and in Europe, it’s even worse, with young farmers making up less than 5% of the sector. For the American Farm Bureau, this shortage is the number one issue facing agriculture today, leaving ag marketers to seek unconventional approaches to find new recruits. Earlier this year, John Deere’s marketing team announced that they were hiring a “Chief Tractor Officer” — a TikTok star named Rex Curtiss, who would try to catch the attention of young people and speak for the next generation of farmers. Meanwhile YouTube star MrBeast has built a 100-player farm simulation to market Dairy Farmers of America. For those tasked with agricultural recruitment, seeking new approaches to getting more young people into farming requires creativity.

Farming Simulator attracts an agriculturally curious audience rooted in learning the ins and outs of farming, from breeding livestock to growing crops and selling assets; this includes some real farmers who want to wind down from a long day of driving actual tractors by driving a virtual one at night. Developed by Giant Software, the game typically has 44,625 live players and is based on the real-world challenges of both American and European farms.

Farming Simulator’s biggest competitor, Stardew Valley, has a worldwide gaming community with more than 120,000 live players in a 24-hour cycle with a largely non-farming audience. The game’s focus isn’t designed to depict the real challenges that farmers face, but worldbuilding that reinforces self-reliance. Its premise mirrors what many young farmers face today: someone who has inherited their grandfather’s once plentiful farm. The goal is to transform decaying fields into lush, fruitful landscapes with fertile crops and a potentially lucrative future.

Stardew Valley creator Eric Barone’s inspiration draws from the popular 1990s farming game, Harvest Moon, developed by Japanese video game designer Yasuhiro Wada. Wada drew from his childhood growing up in the countryside and a desire to develop a role-playing game without any combat. For Barone, the game was so evocative because it spoke to the core power of agriculture: Civilization doesn’t exist without farming.

Many of the popular games on today’s top charts — from Call of Duty to Grand Theft Auto and Madden NFL 25 — are focused on themes that evoke violence, sports, and conquest. What sets Stardew Valley apart as one of the most popular indie games of all time is its unconventional focus on resiliency and self-reliance at the heart of human desires. “I think that there’s something about the game that taps into that deep desire that we have to live off the land and make small goals incrementally towards growing and expanding and creating a home for yourself,” said Barone.

“I think there is a real challenge in converting someone into becoming a real farmer, because I think the reality of actually being a farmer is not going to be the romantic ideal.”

While the game doesn’t necessarily intend to capture the real world experience of farming, Barone’s inspiration for designing the game is loosely inspired by his experience of growing up in the Pacific Northwest, where his parents prioritized sourcing fresh food from local farms. “My parents were always supportive of small-scale, regenerative farms, and growing up around them definitely influenced the themes in the game,“ he said. ”Some of the types of crops and foraged ingredients that you’ll see — such as the salmonberries — are inspired by this area, but players thought I had made them up.”

Despite the creative and unconventional marketing recruitment efforts that organizations like Dairy Farmers of America and John Deere have taken in recent years, no one from the agricultural sector has ever approached Eric Barone to collaborate. But even Barone isn’t convinced that gaming has the potential to effectively attract a new generation of agriculturalists. “I’ve seen a lot of things on Reddit, and people have emailed me to tell me that because of Stardew Valley, they were inspired to start growing vegetables or start a garden,“ said Barone. ”I do think there is something about playing the game and then having this slightly romantic idea of farming which could inspire people to be interested in it. I think there is a real challenge, though, in converting someone into becoming a real farmer, because I think the reality of actually being a farmer is not going to be the romantic ideal.”

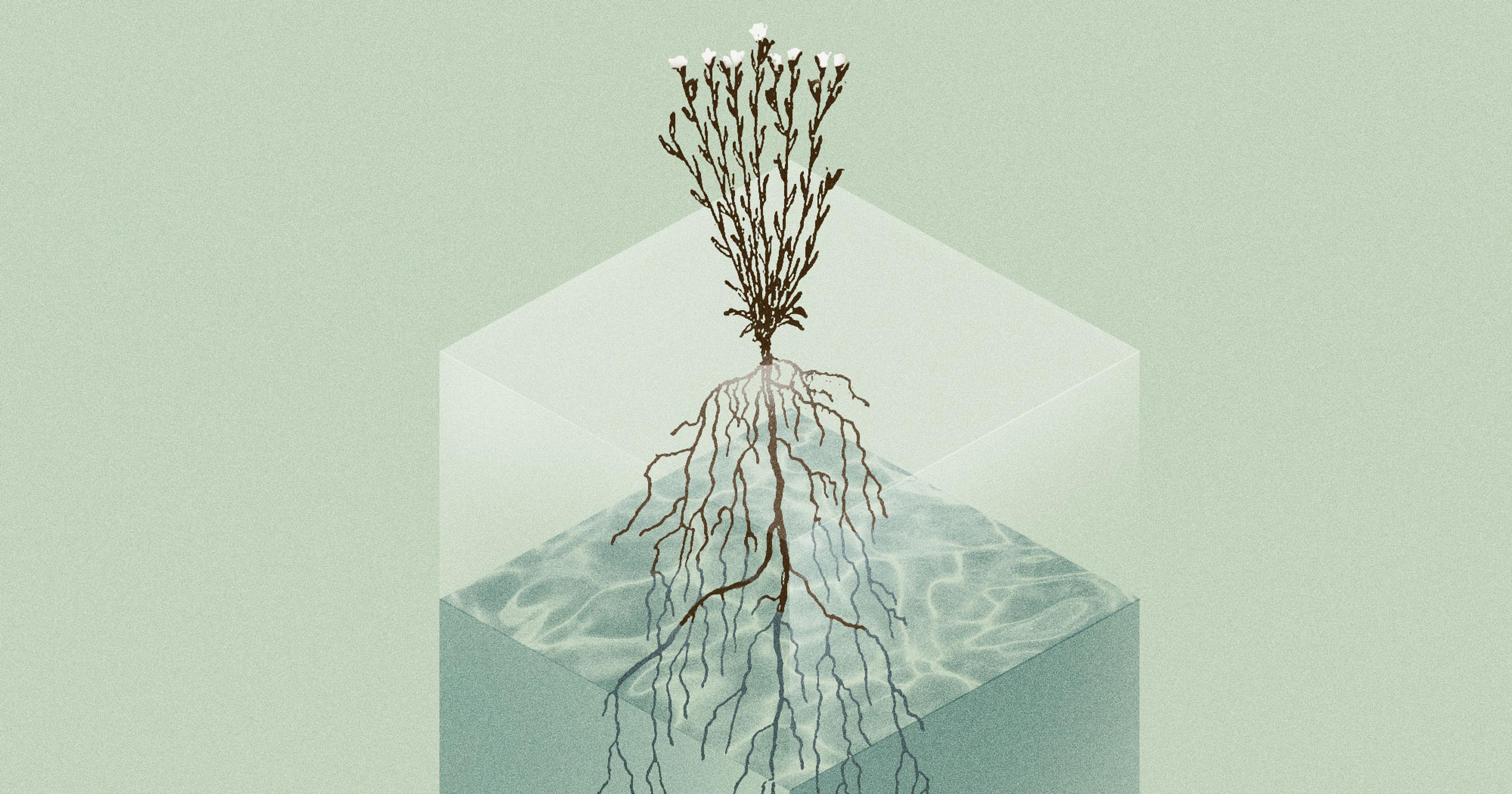

Whether or not his game could help with recruitment, Barone does worry about the potential implications that the aging global farming population poses to localized food systems. “The thing that I worry about … is that the future will be in the direction of just a very few huge corporate farming businesses that will produce all of the food for everyone. I would like to see farming become more decentralized, where there’s more local farmers doing small enterprises like you might do in Stardew Valley.”

Real-world applications aside, an enduring appeal of games like Stardew Valley is using world building as a form of escape. Barone said, “People will approach me and tell me things like, ‘The game was an escape for me during a tough time,’ or I often hear people started playing it during Covid, and it made that experience easier to give them a form of escape.”

Regardless of the potential effectiveness of virtual gaming successfully recruiting new farmers, farming remains the enduring, analog system that’s a backbone of all other human endeavors. “Farming is living in what’s productive, working with your hands, and contributing to the community in a tangible way, as opposed to everything being digital, abstract. In a way, it’s almost kind of punk, because the world has become so abstract and digital, and everything is in the cloud, and everything is intangible,” said Barone.