Solarpunk is the artistic response to cyberpunk’s gloom-and-doom vision of the future, where technology is harnessed for the power of good.

Cyberpunk was once a thriving subculture that emerged from the science fiction scene of the early 1980s, a reaction to the utopian vision of scientific progress that was popular in the 1950s and ’60s.

Art, entertainment, and media had convinced Americans that the glossy, tech-forward future portrayed in The Jetsons or Star Trek was right around the corner. Cyberpunks posed a counterpoint, that the future we were heading for was bleak. If we didn’t do something about it, its proponents suggested, our lives would be consumed in neon-drenched urban sprawls where unchecked technological progress ultimately destroyed us. In the 1980s and ‘90s, this vision resonated with the masses. And in a way that many don’t realize, it still does. Even if cyberpunk art has fallen out of fashion, its perspective is now so ubiquitous that it’s arguably our de-facto vision of humanity’s future.

The cyberpunk movement’s success is as much a blessing as a curse. We were woken up to the truth with enough time to take action. Yet in many ways, cyberpunk made most people too pessimistic to think we could change things. By cementing our image of the future as a dystopic one where the outcome always favors the oppressors, it made the masses lose hope in any attempt to fight back.

This is where solarpunk comes in. Though both movements accept the danger of unchecked technological advances, solarpunk makes a conscious choice to envision a plausible world focused on spirituality, craftsmanship, community, and natural/technological harmony — all powered by renewable energy.

Solarpunk is what people in the science fiction community label as “low-sci-fi.” This means that solarpunk fiction’s focus is not on futuristic tech. Instead, the social aspect of the setting takes center stage, and how generally positive tech advancements have influenced communities. Notably, writers either use realistic science only a couple of years away from our futures, or they opt for speculative futures where beneficial tech we already have is in widespread use.

Since our environment is intrinsically tied to human development, one of solarpunk’s core missions is advocating for a transformative approach to agriculture. In a true green revolution, rooted in the principles of solarpunk, farms wouldn’t just focus on production but on cultivating a sustainable, symbiotic relationship between technology and nature that prioritizes our planet’s — and its inhabitants‘ — collective health.

So, what does solarpunk farming look like when practiced by real-life adherents?

To Navarre Bartz, former Charlottesville director of the Thomas Jefferson Soil and Water Conservation District, “Solarpunk farming has to be regenerative. Whether through permaculture, healthy soils, or something else, solarpunk agriculture keeps biological cycles going and ideally leaves the land and water around it healthier than when you started.”

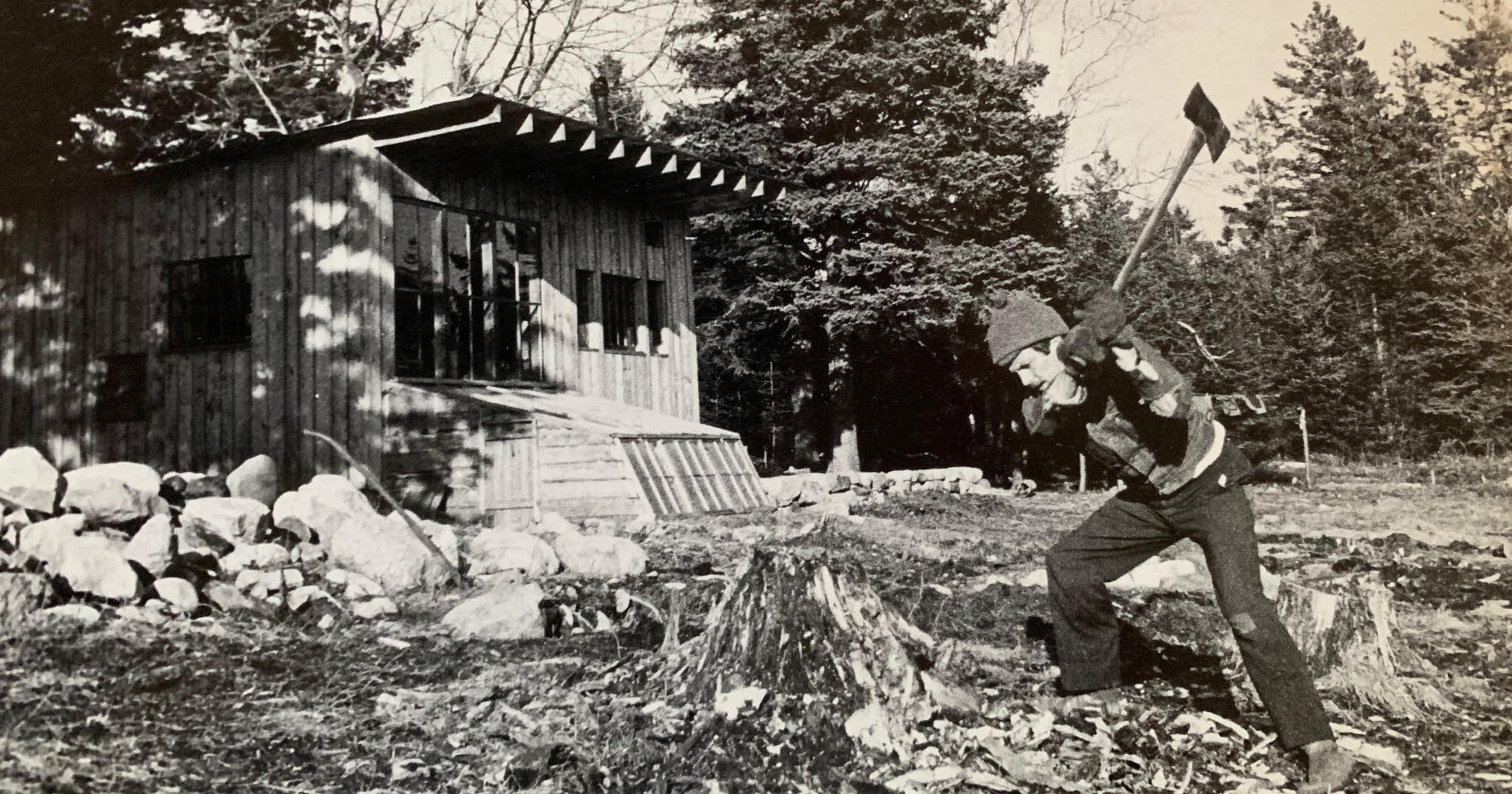

“We’re finally starting to realize traditional and Indigenous farming methods that work with the land and not in dominance over it are the way to go.”

Bartz now runs the YouTube channel Solarpunk Station, hoping to spread his movement to the masses with his material science and engineering background. Since solarpunk is decentralized and there’s no single text anyone can point to, his videos answer questions the average person wonders about when first encountering the movement. And even if it doesn’t fully hit the mainstream, Bartz is optimistic about the general trajectory of agriculture in recent years, feeling that it falls in line with the solarpunk ethos:

“It’s taken a long time and a detour through the ’Green Revolution,’ but we’re finally starting to realize traditional and Indigenous farming methods that work with the land and not in dominance over it are the way to go.”

Other voices in the solarpunk community focus on spreading solarpunk farming techniques through social media. Farmer Andreas George, known to his followers as Solarpunk Farmer, has amassed tens of thousands of followers across all his accounts, with whom he shares videos explaining how the average American can implement these practices on their farms.

George launched his social media identity to promote small-scale aquaponics technology, initially his primary focus. This methodology involves farming fish and plants in a recirculating aquatic ecosystem without using soil. However, many of the practices he now teaches and advocates for (such as cover crops, companion planting, sheet composting, and deep mulching) fall under a “regenerative agriculture” umbrella and are seeing a rise in popularity — no matter what name they fall under.

“People are beginning to realize just how easy and effective covering your soil with mulch is at retaining water and conserving nutrients, for example,” said George. “Cover cropping, which greatly improves soil health and supports insect biodiversity, is a traditional farming practice dating back thousands of years, which is now displacing the use of factory-produced fertilizers and soil amendments in home gardens and giant industrial farms alike.”

While George still advocates for aquaponics, he only considers them solarpunk when applied in an urban setting on a small scale. (There are plenty of disputes as to what is and isn’t true solarpunk on Reddit’s r/solarpunk, a 129,000+ member subreddit.) To condense his thinking, aquaponics and hydroponics are simply too costly when scaled up. They are only practical and environmentally responsible when used in limited, clean soil spaces for serving individual communities.

“I think that as long as you’re trying to improve your surroundings by growing things, that makes you [a solarpunk farmer].”

When the Covid-19 pandemic started, George realized that somebody should integrate existing infrastructure (like public water systems, electricity, and global supply chains) into solarpunk farming practices. The practices he now advocates for are sourced from diverse practitioners and researchers worldwide. This is tied to his growing interest in reviving traditional ecological knowledge practices and a restoration-focused approach to agriculture. One specific practice he has promoted is JADAM organic farming.

JADAM is rooted in the Korean peninsula’s Indigenous farming systems. It was established in the ‘90s by agricultural scientist and organic farmer Youngsang Cho to challenge agrochemical giants‘ growing dominance and increasing input costs. Another practice George has been exploring is syntropic farming, a fusion of Swiss and Indigenous Brazilian farming practices that systematically approach “restoration by use.” In essence, it involves restoring an ecosystem in an area by interplanting a succession of food plants and local native species that evolve their own ecology.

But regardless of which of the methods George promotes, he explains that they all tie into the broader goal of empowering any farmer or gardener to divest from mainstream consumer growing. As he explained it:

“Given [consumer farming]’s reliance on the fossil fuel economy, control of nature through ecocide (i.e. monoculture, herbicide, and pesticide use), and costly, disposable products, the modality it represents is everything we are seeking to fight against as solarpunks.”

To those out there worried that solarpunk farming may not be for them, farmers from all over the existing community insisted that even if one does not have a farm, practically anyone can garden. Bartz, in particular, went as far as to say:

“Some people might quibble over distinctions of gardener versus farmer based on the size of your operation, but I think that as long as you’re trying to improve your surroundings by growing things, that makes you one.”

It’s important to note that the farming techniques mentioned here are not exclusive to solarpunk; many are in use in farms all over the world. What makes solarpunk important, however, is that it offers farmers an ethos, a philosophical underpinning promoted through its art that could guide agricultural movements into the brighter future we’re all dreaming of.